What is "cartooning?" It means different things in different milieus of the comic-book world. Comics published by large companies seem unconcerned with the term, preferring writer, penciler, inker. If an employee combines the last two terms into their practice, they are designated simply as "artist."

I think it's safe to assume that for readers of this website, and for the artists of the past that shaped the aesthetics that this publication champions, "cartooning" means combining all three practices (with "inking" being either assumed or not applicable). This would, in theory, provide a rather wide tent for what this art form can mean. Words and pictures in some degree of cooperation.

But the discussion of cartooning is, of course, far more conservative than that. While all approaches are encouraged or paid lip service to, a "true cartoonist" is defined rather narrowly, even in our pushing-the-boundaries corner of the form.

What always surprises me about any out-of-left field comic receiving the "that's interesting, but it's not cartooning" or "pretty experimental!" response is that the beginnings of comics resemble the contemporary avant-garde very closely. Lyonel Feininger's The Kin-der-Kids has no relation to John Romita Sr., but doesn't look totally foreign to work seen in an underground zine. What's more, The Kin-der-Kids was not a lost and forgotten piece of comics history---it was widely circulated upon publication and has been discussed with admiration ever since.

Importantly, work that has similarities to Feininger today is not done in tribute or homage to The Kin-der-Kids---rather, work like this is made naturally, often by people unaware of (or with non-worshipful attitudes toward) early comic-strip history, suggesting that this approach is a natural part of cartooning's DNA.

But this leads us to a question: what is this generally agreed on notion of orthodox cartooning and how does Feininger differ from it?

If you want orthodox, I think Jack Kirby's Fantastic Four #51, which contains the story "This Man... This Monster!" might be a good place to start.

The obvious pitfall of using this particular comic as a definition of pure cartooning is that one person, Stan Lee, is listed as the writer, while Kirby handles the penciling. However, I think we can argue that this fits the base level definition of cartooning in that, by this time in the Fantastic Four's history, Lee's "writing" contribution barely exists. Different views on the accuracy of this viewpoint have been debated for close to half a century now, but we are going to proceed with the assumption that this comic is as much written by Kirby as it is drawn.

I should note that for years I resisted Kirby as a reader---his work was so influential that it felt stifling to engage with. But Kirby can't be easily dismissed or ignored (when I look at a Kirby page, it's hard to resist reading it), and over the years, I've allowed myself to engage with more of his work. The pleasures of his comics are undeniable. He is worthy of the vast respect he commands. His work is beautiful, exciting, unique, and made with the utmost care. But for our purposes today he is a foil.

"This Man... This Monster!" is an airtight masterpiece, created at almost the midpoint of Kirby's career and representing a peak of achievement. A self-contained story, it begins with a disillusioned Thing lamenting his non-human status. An evil scientist exploits the Thing's vulnerability in order to assume his powers and act as an impostor, returning the Thing to his natural Ben Grimm state. The Fantastic Four believes the fake Thing to be real, and Reed Richards entrusts him with his life for a mission in "the negative zone." Impressed with his selfless nature, the impostor sacrifices himself to save Reed. As the impostor dies, Ben Grimm returns to his form as the Thing.

All of this action (and lightly moral melodrama) almost reads itself to you. Every gesture, emotion, plot point is unambiguous. Nothing is left to (mis)interpretation. This is done, I believe, in two major ways: first, Kirby doesn't just draw anything required of him, he knows how reduce it to a coherent world of icons. A table, a man, the cosmos, anger, depression: they all have a correct way of being rendered and communicated within Kirby's visual world---a world he worked on refining and developing tirelessly for close to sixty years. Everything is reduced to a certain level of visual complexity so as to achieve a reality that synthesizes from top to bottom. Imagine something, imagine anything... it's easy to conjure up in your mind how Kirby would draw it. Does this equal cartooning? Possibly.

Second, Kirby knew how to borrow cinematic techniques without showboating. He crops his characters, sets up "shots," and establishes location for maximum clear storytelling, all while preferring not to communicate to the sophisticated reader that he "understands" the tools of cinematic storytelling. The interest here is telling a story solidly and clearly, using whatever effective methods exist. All "mainstream" cartoonists of the day used cinematic shorthand in their comics, and I'd never argue that Kirby was the most concerned with this approach or the most influential (Caniff and Sickles come to mind first). But his comics probably merge the two mediums the most seamlessly. None of this makes Kirby subservient to film---the fact that one artist can do the work of a director, actors, cinematographers, a costumes department, and more is one of the amazing potentials of orthodox cartooning---a potential that Kirby realized and fulfilled many times over. Kirby's comics read like a big-budget film that is highly personal: a blockbuster with the undertone of one man's emotion beating through every moment.

So... why wouldn't such an approach be endlessly influential? Why shouldn't most cartoonists work in such a mode? In telling a story visually, Kirby's synthetic visual approach is highly effective. It's also a meaty gauntlet that Kirby set down, meaning there's plenty for generations upon generations to explore and build on. And even if that bombast that the cinema elements provide are removed, and you're a Dan DeCarlo-type cartoonist who draws everything as an icon that gels with everything else on the page, there's much to admire and refine. Cue a perfect spread of Jamie Hernandez art:

Now, we exist in a moment where Feininger, Kirby, and Hernandez are all beloved. None of their approaches has been debunked or shunned. And yet, when we look at the above Feininger page, it doesn't necessarily seem part of the medium in the same obvious way that Kirby's "This Man... This Monster!" page does. If you think of painting, an Impressionist canvas doesn't seem like a pleasing anomaly within the current hegemony of abstraction. It appears as an established fact of painting history, and one that is in constant dialogue with the art of today: built upon, reacted to, rejected, or newly embraced, but still an integral part of what a young painter will reconcile with as the potential that their medium offers. Early newspaper cartooning, on the other hand, takes everyone's breath away, but feels like a medium from a different universe. There's no grid, the cartoons lack strict "cartoon integrity" (meaning they look exactly the same from the first panel to the last), and the narrative drive is off-kilter at best, non-existent at worse. Why is this, the conservative crowd yells, cartooning? And why bother with it?

Here's a reason why: Feininger's characters aren't engaged in a simulation of reality, and their purpose isn't to tell you a clear story. Instead, they offer a different view of what cartooning could have been. Movement, exploring environments, sounds, color are what's happening here. And the loose narrative whips you around a world to confront you with these sensations. A static image or painting would bring you one arrangement of these experiences. But a comic with these elements in play allows for a richer template (more and more sensations without descending into sloppy overload) and for the experiences to be controlled through time and space. Sound familiar?

The promise and visual exuberance of early comics has been explored now for decades within cartooning, but mostly regulated to the underground, especially in publications like Paper Rodeo---a free giveaway newspaper featuring contributors like Matt Brinkman, Brian Chippendale, and Joe Grillo (among many others).

Kirby's influence is so great, though, that most of the discussion around Paper Rodeo at the time (and to this day) decided to focus on how the publication could be viewed as a continuation of Kirby's creative sci-fi. This alone was enough to deem the Fort Thunder generation as a break from the norm of the alternative/underground: young artists who embraced Kirby's orthodox cartooning rather than the more cartoony (but still traditional) heroes (Schulz, Stanley, Kurtzman) of Charles Burns, Dan Clowes, and Chris Ware. Focusing on an embrace of genre and world-building rather than the break from the shared priorities of Kirby AND Schulz seems to miss the forest for the trees. Paper Rodeo's format, whether or not intentionally chosen to honor the beginnings of comics, should have served as an obvious lead-in. The beauty and visceral punch of early newspaper strips was very much part of the publication. Just because cinema happens to exist when these comics are made doesn't mean film needs to be a concern for cartooning. The free-of-cinema work of Feininger feels more relevant within these pages.

The comics and zines from this era and movement are considered fringe in terms of what the medium "is." Some readers even considered them offensive affronts against the very idea of cartooning, rolling their eyes at self-indulgent experimentation. This points to how conservative "alternative comics" was even in the last decade, and continues to be. Art cartooning is still judged successful when most of the things Kirby did in "This Man...This Monster!" are applied to non-genre topics. Emotional and intellectual themes are where a serious cartoonist should apply themselves, as long as grids and clear storytelling are adhered to. In fact, Clowes, Burns, and Hernandez took the model of storytelling set down by Kirby and refined it to heights most '50s and '60s artists probably wouldn't have anticipated. Without an oppressive monthly schedule to adhere to, replaced instead with the empowering mindset that comics are really and truly art (something that might have been a more hard-won concept for Kirby), refining craft comes to the forefront for these artists. But it's craft largely within the Kirby (or Schulz or Johnny Craig) model.

Now, again, it's hard to critique this. Kirby and Schulz are artists of great merit and the alternative generation's processing of them yielded (and continues to yield!) rich artistic results. And yet, even as the divide has dramatically lessened in recent years, the power of cartooning as a medium still remains very unclear to the public at large. Part of this, in my view, lies with focusing too closely on this specific mode of cartooning as the only worthwhile path. The view of Fort Thunder as "noteworthy but experimental (at best) cartooning" is not an anomaly. All too often, people who makes comics that resonate with the public at large are hardly ever discussed as cartoonists.

Edward Gorey could arguably be the most read cartoonist of all time. Comic-book stores know to carry his books because people read them and buy them. His work is rightly held in high esteem by children, proving that it fulfills at least one of the Kirby standards: clear storytelling. But Gorey's surrealism (not surrealism in the "weird" sense but in the truer meaning of the term: "there is another world within this on"') qualifies him as of the select few artists who use words and pictures in as intellectually and emotionally expansive way as possible. And for this, the world embraces Gorey, an undeniable treasure of American arts. Comics, of course, omits him from the Eisner Hall of Fame (Roy Thomas being a more important figure, clearly) because... he didn't work with a grid? The text is... on the other page? The argument cannot be made that Gorey's text and images can be separated, thus making him a true blue cartoonist. And yet... Roy Thomas (let the record show that I cherish Alter Ego magazine).

Shel Silverstein might be a possible rival to Gorey for the "most widely read" cartoonist title---what parent hasn't read at least one of Silverstein's books to their children? They're ubiquitous and hugely successful. Like Gorey's, they're also wildly creative. Even the most conservative comics person can see the skill in a Silverstein drawing (the above example does essentially what Kirby does: reduce the human figure to a caricature so as to appropriately intertwine with the tone of the text). Still, not only is Silverstein absent alongside Gorey from the Eisner Hall of Fame, he didn't make the far more progressively minded Comics Journal Top 100 list in 1999.

Now, of course Silverstein and Gorey don't care about either the Hall or the List. They are universally acclaimed artists whose work will last for some time. But why does comics shy away from them?

Does it matter? Great work in the mode of Gorey will be produced to varying degrees of success whether or not "comics" certifies it. But if we often wonder why even great comics feel so marginal alongside film or painting, our obsession with one type of cartooning above all others might be part of the reason.

Comics seems to react in an extremely hostile way to people who break with the unwritten rules. Within this magazine, cartoonists like Todd McFarlane have received many words of derision. Yet artists and fans loved these artists in their heyday, and continue to stand by their work. McFarlane, like Gorey and Silverstein, made extremely commercially successful work. Yet McFarlane's characters breaking the grid, the overly expressive facial expressions of his characters, the "how many lines can I fit in this drawing" aesthetic, and the sheer wildness of it all made him a joke to any connoisseur. "Yeah he can draw and the kids love it, but he's no JACK KIRBY."

But McFarlane and his ilk loved Kirby. They correctly viewed Kirby as an artist, and as artists themselves, they wanted to express themselves as uniquely as he did. With the general harrummph that McFarlane's work elicited from all corners of the comics world (except the fans of course), it seemed as if he missed exactly what you're supposed to get from Kirby: you're supposed to emulate him. By this logic, John Byrne is doing everything the right way and all-out self-expression is not a trait of true cartooning.

Julie Doucet oddly connects to McFarlane on this point. Doucet has remained my personal favorite cartoonist from the minute I saw her work and that's no doubt true for many others. Doucet's stories are often short explorations of highly specific emotions, fears, or strands of thought. Fantasies are portrayed, but not as poetic expressions. Still, figure drawing and loose grids are employed: it's comics.

I have a personal theory as to why Doucet abandoned comics, one that relates to the context of this column but might not bear out factually. Anyone who wants to correct me should do so. But bear with me: Doucet, being a extremely sophisticated artist, continued to sharpen and evolve. Her mature comics work, My New York Diary, is as sharp a piece of traditional cartooning as one can find in the alternative era. But after that story, Doucet leaves comics. My theory is that Doucet looks at what people define "real" comics as, pushes her work in that direction, and thinks, "Well... why bother with all this if this is what people want?" Her early and later work are, to me, without flaw. But I'd argue that the comics community's view of what a serious artist must apply themselves to is a pressure that doesn't need to be grafted on to every artist. And yet the view is so dominant that it's hard to avoid. Someone like Doucet can master the ins and outs of traditional cartoon integrity but probably notices quicker than most what a closed system it is, how much feeling it excludes and how much one gives up to offer one's entire art up to it.

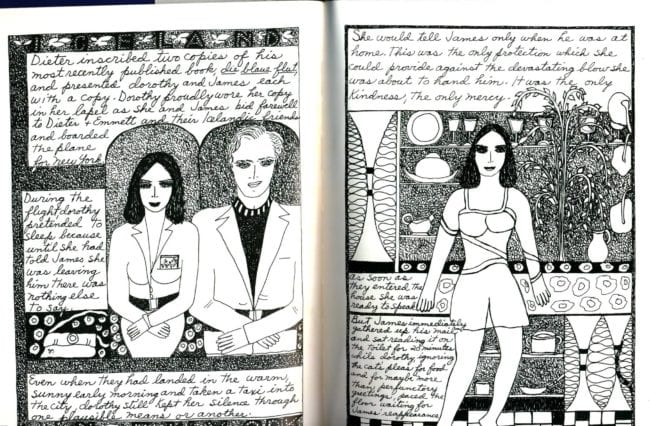

Someone like Dorothy Iannone, working completely outside of the comics community or the influence of its idols, is free from this pressure. Iannone tells autobiographical stories about her life with words and pictures that cannot be separated. Why is her work not a part of comics culture in the same breath as Seth? The situations in her work are far more heartbreaking, the emotions they illicit cut deeper. Auto-bio cartoonists like Joe Matt are constantly celebrated for their "honesty," but when we look at Iannone's An Icelandic Journey, we see real emotional honesty as the collapse of one relationship and the beginning of another is chronicled. Comics associates honestly with cringe-worthy shock, Iannone with awareness of the complexity of feeling. Which makes more sense to people in general? The one that uses panel grids and loves the simplicity of Charles Schulz? Or the one that doesn't emulate any master but instead uses words and pictures in the way that they must be used for this specific narrative.

If Feininger demonstrates to us the freedom inherent in cartooning, Iannone and Doucet bear it out, as do countless other artists working within comics today. In 2017, most young artists will approach cartoning with a very free idea of what is permitted. Raina Telgemeier and Allie Brosh both blazed paths that will be explored with gusto. Does allegiance to any set of rules affect anyone anymore?

I think advocating for approaches that don't cohere with Kirby or Schulz or DeCarlo is important in building a commitment within developing artists to outdo themselves within the set of rules that they have established for themselves. Iannone's system is her own, and her commitment to it builds up to a masterpiece like An Icelandic Journey. A belief in the lessons of Johnny Craig gave Clowes a reason to focus on refining his skills in that tradition and build upon the masterpieces of those that came before. Craig is legitimate, so what can be done with his approach? Similarly, with a growing community of artists making comics completely on their own terms, an acknowledgement that in the tree of cartooning, Kirby and Iannone are equally strong branches might be a good start. These days, we often talk about encouraging artists with the logistical support of comics shows, community, and payment. But proclaiming the open promise of cartooning loudly and passionately might be just as important in keeping some people who belong here committed to their project. Being acknowledged within the context of cartooning mattered for those who built on the lessons of Schulz and his ilk. Let's see what masterpieces those outside a particular sphere of influence will do when we greet them with the same welcoming eye that we've kept so long on Kirby.