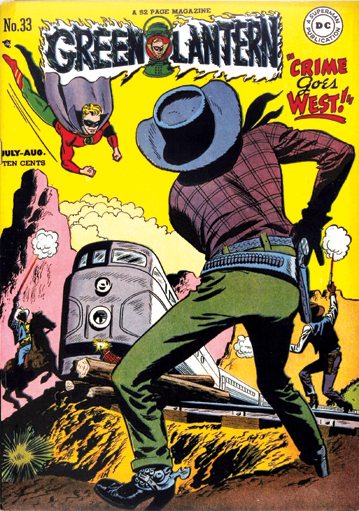

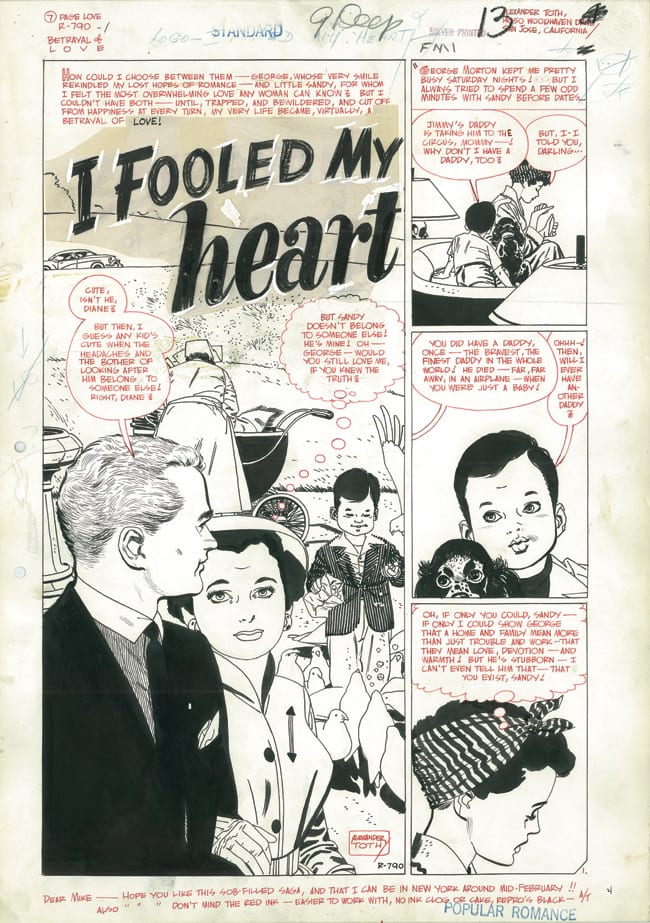

Genius, Isolated, by Dean Mullaney and Bruce Canwell is the first volume in their three-volume series, The Life and Art of Alex Toth. It is, to put it mildly, an astounding achievement. Through thoroughly researched text and a gob-smackingly great selection of visuals, Mullaney and Canwell have done what the best biographers should: Both illuminate their subjects life and decisively show what, precisely, made him worthy of their (and our) attention. Toth, like many cartoonists of his generation, didn't produce a book-length work and nor did he create a body of work that, due to his publishing record, was easily collected in book form. So those of us who heard from the likes Jaime Hernandez how great he was were left to just pick through old magazines and anthologies, looking for the one story that would prove it. Genius, Isolated gives us all the proof we need. At 325 over-sized pages it reproduces his finest stories from the 1940s and '50s (more on that below), often from the original art. Toth's prowess as a designer and draftsman is shown to be unparalleled in these pages. His deft, even subtle page designs only surpassed by his sure line and viciously good sense of space. Moreover, the book situates Toth in both illustration and comics history, amply explicating his aesthetic and personal influences. The narrative running through it, and again beautifully complemented by photographs and letters, is Toth's life first as a fan, then as a hardscrabble freelancer, and finally as a hot-shot, somewhat difficult, star artist for DC and Standard. Canwell provides an excellent snapshot of life as a freelance in the 1950s -- who the players were, what the industry was, and how Toth survived it. This book is, for me, a game-changer: The first (literally) expansive visual biography of a classic comic book artist that manages to show and tell just what made the man and the work.

Genius, Isolated, by Dean Mullaney and Bruce Canwell is the first volume in their three-volume series, The Life and Art of Alex Toth. It is, to put it mildly, an astounding achievement. Through thoroughly researched text and a gob-smackingly great selection of visuals, Mullaney and Canwell have done what the best biographers should: Both illuminate their subjects life and decisively show what, precisely, made him worthy of their (and our) attention. Toth, like many cartoonists of his generation, didn't produce a book-length work and nor did he create a body of work that, due to his publishing record, was easily collected in book form. So those of us who heard from the likes Jaime Hernandez how great he was were left to just pick through old magazines and anthologies, looking for the one story that would prove it. Genius, Isolated gives us all the proof we need. At 325 over-sized pages it reproduces his finest stories from the 1940s and '50s (more on that below), often from the original art. Toth's prowess as a designer and draftsman is shown to be unparalleled in these pages. His deft, even subtle page designs only surpassed by his sure line and viciously good sense of space. Moreover, the book situates Toth in both illustration and comics history, amply explicating his aesthetic and personal influences. The narrative running through it, and again beautifully complemented by photographs and letters, is Toth's life first as a fan, then as a hardscrabble freelancer, and finally as a hot-shot, somewhat difficult, star artist for DC and Standard. Canwell provides an excellent snapshot of life as a freelance in the 1950s -- who the players were, what the industry was, and how Toth survived it. This book is, for me, a game-changer: The first (literally) expansive visual biography of a classic comic book artist that manages to show and tell just what made the man and the work.

I interviewed Mullaney and Canwell a few weeks ago. We have differing opinions on all sorts of things, but their answers explain much of what makes this book so worthy. As a fellow historian, I'm still, weeks later, in awe of it. Anyone with an interest in the medium should own and study this book. It's one of those.

Dan Nadel: Broadly, were you concerned about writing a hagiography? I am impressed by your willingness to show Toth as a flawed character -- a rarity in comics biographies. Were there particular traps you had to avoid? Stories you had to vet (the Julie Schwartz story aside)? And what was your standpoint about the importance of Toth's personal life to the story of his art? For example, the text places an emphasis on his need for both mentor-ship and conflict -- sometimes simultaneously -- rooted in his upbringing. This is not an unusual stance to take, but I wondered how it impacted your narrative.

Dean Mullaney: From my initial contact with Alex's children, I made it clear that Bruce and I intended to produce an honest biography. Virtually every comics biography ever written has been laughably laudatory ("Everything Joe Artist ever drew was fantastic"), without realistic context ("He was the greatest of them all…"), or a deliberate slam job ("Let's knock the icon down a peg or two"). No cartoonist—no person—has led a life that can be discussed in such black-and-white terms. Bruce and my goal was to present not just the art, but the life of Alex Toth. By investigating and analyzing his personality, his relationship with other people—peers, fans, friends, family—we came to better understand him as a human being and how that personality affected his professional work. Probably the most satisfying reaction to the book that Bruce and I have received has been from the children, who have told us that they learned a great deal about their dad.

Bruce Canwell: Was I concerned about writing a hagiography? No, never. Not for a minute. My approach to every assignment is simple: Find the story, then tell it in an interesting and entertaining way. Alex’s story is about a man for whom “great” was never good enough, because “great” was not “perfect.” Tough to write a hagiography around a personality like that! And with Toth, his life affected his art and his art affected his life — the intertwining of the two is key to the story. The challenge was how to most effectively weave that thread into the larger tapestry. I’ll also note that not only did we tell Alex’s four children our goal was to produce an honest biography of their father, each of them said that was exactly what the family wanted — no sugar-coated puff piece, no sensationalistic True Hollywood Story tabloid job. Based on their reactions to Genius Isolated, I believe we’ve met our shared goal.

Nadel: Speaking of cooperation, one thing that is amazing about the book is that you got Marvel and DC to allow you to reproduce so much work. Their stances regarding reprint rights have stymied plenty of otherwise worthy efforts (though it seems to be changing, as with the upcoming Simonson/Thor IDW book). How did you navigate all of that, and do you think their participation is indicative of a significant change in comics history publishing?

Mullaney: Dan DiDio deserves all the kudos for giving permission to reprint “Battle Flag of the Foreign Legion,” and equally importantly, to make sure the deal actually got done. He and DC were also kind enough to grant permission for us to reprint two other incredibly important stories—“Burma Sky” and “White Devil…Yellow Devil”—in our follow-up book, Genius, Illustrated. A friend of Alex’s graciously loaned the original art for both stories; “White Devil…” is particularly interesting in that Alex re-inked some pages after the art was returned from DC. I think DC made an exception to their policy in tribute to Alex, but I just don’t know.

Nadel: I wondered if you could talk a bit about the evolving "DC House Style." He seems to have been the first to really develop a post-Caniff style all his own -- via paring is down and making it simpler. But can you talk about where it was before Toth, and where it went after? And also, broadly, how important house styles were at the time.

Mullaney: I don't think it's offering any great insight to state that in the 1950s and into the 1960s DC wanted a uniform style so that the company could keep the "product" consistent. It was a corporate decision in which writers and artists were not credited. The wonderfully clean and precise Sy Barry inking style exemplified the "look." Julie Schwartz repeatedly said that if he could have had Barry ink everything, he would have. The house style eventually became Carmine's style. After the inception of the Comics Code, it evolved or devolved (as the case may be) into what I consider stiff, dull, one-dimensional storytelling that seemed to purposely avoid any attempts to be emotive. To use a pop music analogy, DC's restrictive house style was the equivalent Pat Boone, Bobby Rydell, and Teresa Brewer. A square peg like Alex Toth does not fit in a round hole.

Canwell: For the biggest companies in comics, house style has been an inevitable by-product of success, hasn’t it? “We’re selling, so let’s determine which qualities in our books are driving sales and try to inject that flavor into all our product.” DC certainly had its share of house styles through its history, and even in its earliest days, Marvel did, as well. There was a reason why almost every major incoming Marvel artist — Buscema, Romita, Gil Kane, Steranko; everyone but Gene Colan — started out working over Jack Kirby’s breakdowns. Oh yeah, Alex worked over Kirby when he dipped his toe in the Silver Age Marvel waters, in X-Men # 12 — look how that worked out!

The maverick runs against the herd, and Alex became more and more a maverick as his career matured. He wasn’t going to march to the beat of another drum — he couldn’t.

Nadel: The stylistic lineage is fascinating to me, and your tracking it through the 40s is rather remarkable. I want to ask about Irwin Hasen, who is not often cited as an influence. How do you situate him as an artist? What did Toth see in him, as opposed to the flashier, more obviously influential Meskin?

Mullaney: I don’t think it’s necessarily an either/or situation. It could very well be that Alex admired Irwin because he was a working professional that Alex wanted to be. Irwin was certainly among the better artists at DC at the time. It’s a question only Alex could answer.

Canwell: I agree: Irwin was one of the most solid artists in the Golden Age DC stable, and a teenaged Alex was savvy enough to see that and learn from it. Add in the fact that, here was a working pro being inclusive and treating young Alex as a friend and a peer — no way Alex wasn’t going to absorb all the lessons he could under such circumstances. And hey — Irwin would eat the Hungarian goulash Alex’s mother made! What red-blooded first-generation American boy isn’t going to appreciate a guy who likes his mother’s recipes from the Old World?

Nadel: Toth's “Battle Flag of the Foreign Legion” is situated as a pivotal story in the book. For 1950 (well, for anytime) it's remarkably advanced -- is its importance an anecdotal thing passed from artist to artist? I ask because it is not in the "canon" like, say, "Master Race" is. So I wondered where its status lies.

Mullaney: Tellingly, Krigstein himself cited "Battle Flag" as a major influence. It seems to me one reason "Master Race" and other EC stories are in the "canon" is simply because EC had an organized fandom that wrote and published articles and perpetuated the fame of its heroes. Is it one of the best comics stories of all time? Sure. But there was no Squa Tront for Alex Toth. His work was passed around not from fan to fan, but in well-read copies from working artist to working artist, just as Noel Sickles's Scorchy stats were passed around from one professional to another. Was Sickles part of the accepted fan "canon" back in the early 1950s? No, but he certainly was near the top of the canon among professional cartoonists. Whose "canon" are we talking about anyway—the "canon" of fans and critics or the "canon" of working cartoonists?

Canwell: I laugh whenever I see self-important terms like “canon” being bandied about. The comics world is so broad and vast and variegated, I suspect no two persons involved in it — as creators, critics, or readers and fans — have exactly the same reading experience, so everyone has his own individual “canon” that emerges out of that experience. Strong work gets noticed, but any given piece — “Battle Flag,” Barefoot Gen, Watchmen, you name it — is viewed through the prism of each individual “canon,” each individual’s unique cumulative reading experience. So to me, “canon” is one of those terms that sounds great, but is essentially meaningless.

Nadel: I’m not much a believer in a comics canon myself, but nevertheless, it’s "Master Race", and not "Battle Flag", that is cited in most books on the history of comics, as well as by most longtime critics. So, while “canon” is not a useful term in the abstract, it does describe a certain consensus. Leaving aside ideas of canonization, what I’m asking is what, for you two, makes this story significant, and how you think that significance rippled outwards, Krigstein aside?

Mullaney: I’m reminded what Dick Giordano told me. “It must have been difficult being Alex Toth,” because he looked at art and saw ways to tell a story completely unlike anyone else. We didn’t title the book Genius, Isolated for drills. We can analyze his art all we want, but it’s an after-the-fact review. What made him break away from the linear, newsreel-type of storytelling and create a new dramatic paradigm? It’s not necessarily the kind of thing you can explain. He certainly couldn’t. He could talk about pen nibs and ink mixtures, but what made him simplify, simplify, simplify until he reached the purest essence of storytelling. Why is “Battle Flag” not as well known as “Master Race?” I think “Battle Flag” is more problematic for a writer to understand. Artists certainly get it. If I may use another music analogy, have you ever read a music critic who could explain what Jimi Hendrix did? They can write reams about Clapton because he had a style anyone could copy. But Hendrix? He’s like Toth, like Ditko. Out there in his own sphere.

Canwell: It’s easy to give “Battle Flag of the Foreign Legion” short shrift, because if you try to verbally describe the story it sounds like the same fundamental construction we’ve seen in a gajillion old DC comics — the “talking” artifact (in this case, the battle flag of the title) narrating a tale in flashback, the hero presented with a clear-cut problem, struggling to overcome the problem, and using the “talking” artifact to help resolve his situation just in time for “The End” to appear in the final panel. It’s when you really look at “Battle Flag” and start assessing the storytelling choices Toth made – that’s when you realize this is an early benchmark in comic book history. There had been plenty of stories that generated artwork (some of it very nice artwork indeed) devoted to telling the story, but here was one in which the artwork elevated the story, making the finished product more than simple melodrama.

As to how “Battle Flag’s” significance spread, I think it went the way so many things spread in the days of yore, before computers and tweeting ... knowledgeable pros and fans “ooh”ed and “aah”ed over it and shared their enthusiasm with those in their professional and social circles. The desire to satisfy the “Oh, you GOTTA see ... ” impulse has launched hundreds of fanzines and thousands upon thousands of discussions down through the years.

Nadel: There is always the problem with Toth (and many others) of the writing. After all, we're looking at these incredible pages mostly in service to bland or uninspired plots. First, is this a problem for you in evaluating Toth's work, and second, if so, do you intend to address it in future volumes.

Mullaney: I long thought it sad that so much of Alex's output was in service of "unworthy" projects like the Dell TV and movie adaptations. On the other hand, it was exactly that work that got me excited about comics in the first place. Two of the earliest comics I remember reading were "Zorro" and "Darby O'Gill and the Little People." I had no clue at the time who drew them; I just knew they were more exciting than "Jimmy Olsen" and "Lois Lane." So, it could be argued that—for people of my generation—those TV and move adaptations WERE worthwhile. In looking at them now, I consider them better drawn and more "worthy" than the typical Marvel or DC comic of the time.

In researching Genius, Isolated, Bruce and I had access to a large stash of letters Alex wrote to Jerry DeFuccio in the late 1950s. In one of those letters, he laments about how many "Stan Lee boys" came to Dell looking for work, but that there was none for them. Remember, this is the exact time when the comics business nearly died. Alex, as a professional cartoonist, was thrilled to have work—any work. Most comics artists left the field for advertising or other non-art jobs, and never came back. In the long run, are those Dell comics less "worthy" of Toth's talent than "Little Annie Fanny" was of Kurtzman's? I'd argue that, looked at today, the Dell books are superior. In working on this book, I've gained a new respect for them. But Kurtzman was also a professional who needed the gig. They loved drawing comics, but it was their livelihood. They weren't part-time graphic novelists or dilettantes who created one story per year. They were full-time professional cartoonists.

Who the hell are we to question a guy trying to earn a living? It's very easy for an outsider or someone who has a different "day job" to criticize what jobs a professional cartoonist accepts. I'll be curious to see what will happen to the part-time graphic novelists or dilettantes as they age: will they become full-time cartoonists who need to be concerned about feeding their families, providing for their children's college education, their spouse's mounting medical bills?

On the flip side of your question is another touchy issue—the "taboo" argument that so many modern graphic novelists are great writers but have very little if no artistic storytelling talent. But that's a whole 'nother discussion.

Canwell: Circling back to the core topic, I admit, I don’t know, Dan — the work is the work is the work, you know? Will there be some upcoming discussion of the fact Alex didn’t always have top-flight stories to work from? Most likely. Is that exactly a news-flash? I don’t think so. And is Alex different from any of his peers in that regard? It’s not like Carmine Infantino or Joe Kubert spent their careers working off scripts by Faulkner or Chandler, after all.

And certainly, Alex had his own ideas about what constituted quality writing — I don’t see those critics who bandy about terms like “canon” stacking up the paeans to Kim Aamodt, but Alex’s views on Aamodt’s work are crystal clear to anyone who reads Genius, isolated. I’m more interested in telling Alex’s story than in shoehorning it into a box pre-defined by the critics.

Nadel: I think that’s very fair about Toth (less fair about contemporary artists, many of whom do in fact earn a living doing graphic novels, and are drawing in a different idiom than classic/modern illustration — but we can argue that over French fries sometime). I think it’s difficult, in some ways, for a contemporary reader to understand the pressures on mid-century mainstream cartoonists. What’s interesting to me is the tension created when someone of Toth’s caliber (who I think of as in an entirely different league than Kubert and Infantino) applies his talent to mediocre material. In other words, the reader has to choose to “turn off” the literary part of her brain and view the comic as a visual narrative, rather than a plot or prose-driven one. That tension is at the core of comic book history. When everything works together (here I think of Barks, Stanley, the war stories written and drawn by Kurtzman, or the Binder/Beck Captain Marvel, Boody Rogers’ output) the comic can be considered as a whole. But with Toth, for the most part, we’re only there for the art. Is that tension of interest to you?

Mullaney: If what you posit is true about contemporary readers, then they should read a little comics history before passing judgment or—God forbid—writing reviews. We can invent all sorts of post-modern constructs about new artistic idioms, but when, for example, I read Harvey Pekar’s stories, I don’t feel any tension just because much of the art is mediocre. To flip your phrase on its side, with Harvey’s stories, I’m “only there for the story.” And happily so. With Alex’s art, I’m gladly there for the art on "Battle Flag", "The Crushed Gardenia", "Burma Sky" (although each of these three are damned good stories, as well).

I think the crux of this argument is that comics reviews and history are primarily written by writers, not by artists. We uncovered a previously unpublished and unfinished 1950s Toth story for the book, which I showed it to about a dozen people, both writers and artists. The writers looked at it with wonder, trying to read the penciled lettering; the artists, on the other hands, were awed by the art. “How did he think of positioning that figure in the foreground that way?!” The writers didn’t see any of that. A writer is more willing to enjoy a story with bad art, just as an artist is more willing to enjoy a well-drawn tale with bad writing.

Canwell: So the tension you’re referring to here, Dan, isn’t a tension between Toth’s talents and his scripts, but a tension between modern readers and the old comics? OK, that’s fair, but isn’t it the same tension that exists between modern film buffs and silent pictures? Faster storytelling paces, Dolby sound, and CGI extravaganzas surely must make it more difficult for contemporary audiences to appreciate, say, Steamboat Bill, Jr. or Modern Times. Yet we expect modern motion picture students to be able to set aside the current paradigm and be able to assess the talents of a Keaton or a Chaplin. Is it too much to ask of students of the comics medium to be able to evaluate visual narrative as well as plot/literary content?

And I’ll reiterate what I said originally – so much of the story content in the comics produced during Toth’s prime years is mediocre. That’s no surprise to us, and if it’s news to some modern-day readers, they should take that as a sign they’re not quite ready to begin evaluating What Has Gone Before. Of course, everyone has to start somewhere ... and Alex’s work ain’t a bad starting point!

Nadel: One more question: What impact do you think L.A. had on the aesthetic development of Toth’s work? I for one, didn’t realize he produced so much while still in NYC. He went to L.A. and to Dell, but the style out there was quite different (Marsh, Manning, and all the animators-turned-cartoonists). Was there any back-and-forth with artists there (aside from his attempt to befriend Marsh)? And do you think place figures in his work? Did it make a difference where he was?

Mullaney: That’s a whole ‘nother conversation. And one that will fit with the second book!