From The Comics Journal #304 (Summer-Fall 2019)

* * *

In my last essay in The Comics Journal #303, I introduced the concept of Expanded Comics: artworks that are not necessarily comics, but they can be read as such — illuminated manuscripts, Mesoamerican codices and Charlotte Solomon’s Life? Or Theatre?, for example. As I wrote, Expanded Comics shows that “comics, as we know and read them now, consist of a tiny fraction of the comics that are possible.”

Greek-Belgian artist Ilan Manouach is one of the most critical contemporary cartoonists and thinkers working today. Manouach critiques the ideologies behind Western comics’ popular “mainstream” and “alternative/comics as art” sets, as well as their respective surrounding cultures. In Katz (2012), Manouach changed each and every animal character in Art Spiegelman’s Maus (1991) to cats. He published this “pirated” edition — which looked exactly like the original except for the crucial animal switch — at the Angoulême International Comics Festival, the same year that Spiegelman was serving as its president. In his Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus, Spiegelman recounts his father’s memories of the Holocaust and the events that led up to it by depicting Poles as pigs, Jewish people as mice and Germans as cats. Spiegelman’s use of animal characters, while acknowledging the “funny animal” history of comics, reinforces ethnic stereotypes and a simplistic, teleological and fatalistic reading of history. Spiegelman’s French publisher, Flammarion, sued Manouach for copyright violation and Manouach was forced to burn all of the remaining copies. This ordeal was described in MetaKatz (2013), whose title refers to Spiegelman’s MetaMaus (2011) and was published with ink created from the ashes of the pulped copies of Katz. MetaKatz is a collection of essays regarding the “Katz affair,” and includes thoughts on copyright, fear of lawsuits, creative rights, appropriation and collage in comics (coined détournement by the Marxist art group Situationist International) and more. These writings show that Manouach’s artistic goal is not just a winking game of trolling but a critical endeavor, which is incredibly lacking in the graphic novel movement which Spiegelman and Maus surely represent.

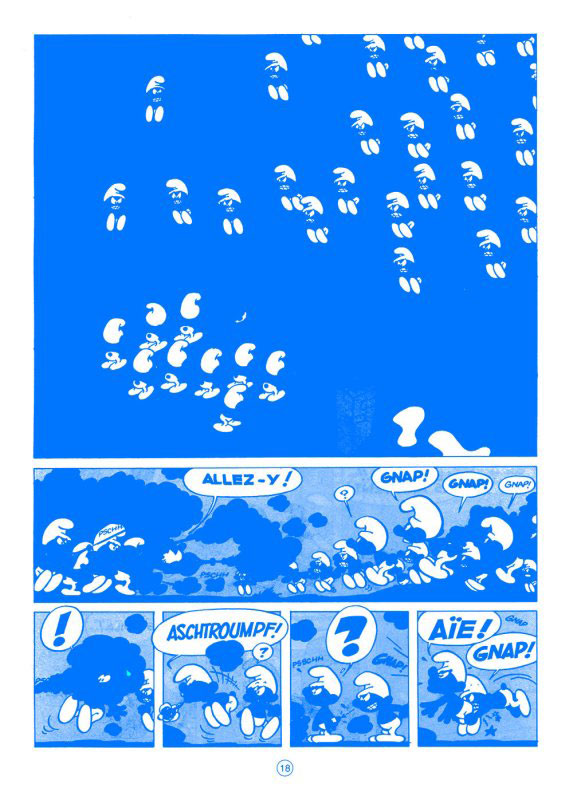

Noirs (2014) is Manouach’s comment on Les Schtroumpfs noirs [The Black Smurfs] from 1963. Les Schtroumpfs noirs was published as The Purple Smurfs in North America due to the racist implication of a black Smurf being inherently pathological and evil. However, Les Schtroumpfs noirs is still sold to children in Europe. Manouach’s Noirs prints Les Schtroumpfs noirs using four shades of cyan, instead of the usual four colors of CMYK (cyan, magenta, yellow and black) that is used for offset printing.

This printing effect leaves the reader unable not only to recognize the “black” Smurfs from the “normal” Smurfs but also the foreground from the background. Onomatopoeias, captions and contextual panel boundaries are meshed together and indistinguishable. We assume that some things as basic as the printing technique and color are neutral and apolitical. But what Manouach shows is that even the most impartial technology conceals an ideology.

Manouach’s “pirated” translation of Hergé’s Tintin in the Congo (1931), Tintin Akei Kongo (2015), is in Lingala, the language spoken in much of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Hergé’s Tintin in the Congo is not sold in some parts of the world due to its racist, imperialist depictions, but is still sold in France as well as Francophone Africa. The fact that it has not been translated into a Congolese national and indigenous language before shows that something is definitely amiss in discussions of the current “postcolonial” world. The matter of translating multinational intellectual properties, which sounds just as mechanical as printing techniques, serves as Manouach’s commentary on colonialism.

Lastly, Un monde un peu meilleur [A World a Little Better] is Manouach’s stretched, square version of Lewis Trondheim’s original title by the same name. Trondheim is one of the founders of the publishing house L’Association, who collectively openly ridiculed “48CC” — the standard 48-page French hardcover album format. They were not merely against the format, however. French mainstream publishers are mostly owned by large corporate conglomerates that kowtow to editorial and sales pressures, while L’Association, in contrast, was formed as a co-op. But as Trondheim and L’Association became more critically and commercially successful, they too began to create “48CC” like Un monde un peu meilleur. Manouach’s reformatting of the work transfigures the format that Trondheim and his publishing house argued is politically biased — but later submitted to — and questions what is so “alternative” about alternative comics.

Manouach pulls the veil off of ideologies behind matters that are assumed to be apolitical in the medium — formats, colors, printings, translation, character design — and demonstrates how indifferent comics discourse has been toward these matters.

Ilan Manouach’s comics don’t have to be read panel by panel to understand them. It is the very act of making them that manifests the artist’s message. Some critics argue whether these works should be regarded as comics or not, which I find unproductive nitpicking. It is more constructive to regard them as Conceptual Comics — or Expanded Comics — and start asking questions that actually matter.

* * *

Ilan Manouach’s own research project “Conceptual Comics (CoCo)” inspired my ideas on Conceptual Comics. My definition is more general in that it applies to any comics work employing the method of creating conceptual art.