The following passages are excerpts from Last Superman Standing: The Al Plastino Story, a forthcoming biography of the artist written by Ed Zeno.

(Excerpt from)

Chapter 2: Harry “A”

Branching Out

In the early days of the comic-book industry most people knew each other, and news traveled fast. Soon after he started working at the [Harry A.] Chesler studio, Alfred “Al” Plastino heard about other publishers needing help. He took samples of his output to a competitor and was taken aback when that company’s art editor informed him that the work was not his. “What do you mean? I should know. I’m the one who drew them,” said Plastino, to which the editor responded, “The actual artist who drew those pages was in here not long ago, showing me the same ones.”

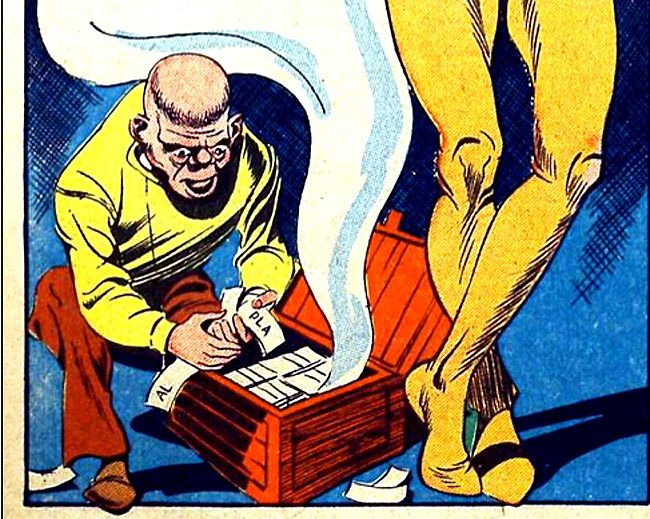

Creators mostly chose not to sign their artwork during the comic-book field’s first three-decades-plus, because bosses might consider it “stealing” if their employees and freelancers decided to moonlight. Nevertheless, Plastino learned the importance of marking his pages since others were taking credit for the work. He and his cohorts sneaked initials — and sometimes even their last names — into splash panels, end pages and elsewhere. An example can be found on the splash page to the Rocketman story published in Scoop Comics #3 (March 1942). At bottom left is a hunchbacked person holding a strap. On the strap is written “AL PLA.”

Plastino remembered: “I jumped around, inking for Fawcett and Funnies Incorporated.” Those weren’t the only companies he moonlighted at. Because he had been published so early in the burgeoning comic-book trade, Plastino rarely had to go looking for additional work. Extra jobs usually found him. He became known as someone who didn’t need coaching and could get the task done reliably. Chesler never knew about Plastino’s side projects, or he’d have been furious. Different studios paid different wages, but $9 per page was probably the most the freelancing young man made during this period.

Art editor Jack Binder left Chesler’s studio in 1940. Before long, he was running his own operation. Plastino noted that he only drew one story for the Jack Binder studio. It was tough to survive in the early comic-book business, and Binder developed a reputation as a bit of a hustler. Plastino remembered how Binder had taken advantage of him when he was at Chesler’s; Binder had the 18-year-old pencil side jobs at little or no pay. Now a bit older and wiser, when Plastino delivered an eight-page story he had both penciled and inked to Binder’s home, he was prepared for what lay ahead. When Plastino requested payment before handing over the art, Binder balked at the idea. That’s when Plastino positioned his hands to show that he was fully prepared to rip the pages apart. Since he had made it clear that if he wasn’t going to be paid for his work no one would have it, Binder acquiesced: he needed the job quickly for publication. Plastino demonstrated early on that, for the rest of his life, few would be able to take advantage of him.

Some of the titles that Plastino worked on during the early 1940s included Dynamic Comics, Blue Bolt Comics, 4 Most, Target Comics, Scoop Comics and Punch Comics, with stories featuring Dynamic Man, Rocketman and Johnny on the Spot. “Dynamic Man is when I first started really catching on with Chesler.” Other assignments during 1942 and 1943 starred Captain America, Sub-Mariner, the Vision and Patriot.

Plastino recalled that he only inked the Captain America stories. The underlying pencils were very loose, but very good; they may have been by Jack Kirby or by Joe Simon. Though he was uncertain who drew them, they taught him a good deal about page layout and action. Without firm deadlines, Plastino took time to work at a slower pace, tightening up the pencils before he embellished. When he was around 20 years old, he did his side jobs at home in the Upper Bronx before he brought them into the city.

The Next Frontier

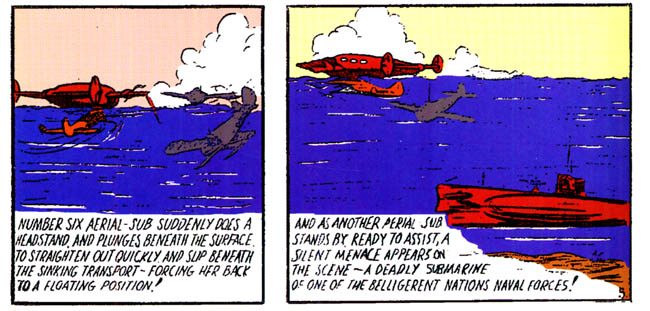

For the publisher MLJ, Chesler’s shop produced the early Pep Comics, which featured the first truly patriotic comic-book superhero: the Shield. Plastino likely saw the underwater airplanes that appeared in Pep Comics #3 (April 1940). The Shield called these ships that went under the sea — then emerged from the water and flew—“submaplanes.” One of Plastino’s moonlighting jobs included inking some of the exploits of antihero Namor, the Sub-Mariner, over creator Bill Everett’s pencils. Everett’s recurring “aerial-submarine” first appeared in Funnies Incorporated’s Marvel Mystery Comics #4 (February 1940). Plastino remembered inking one of the stories in which the intriguing device appeared: “In Sub-Mariner there was a machine that would come out of the water and the wings would come out and take off.” This may have inspired Plastino to design a possible secret weapon for the U.S. military.

(Excerpt from)

Chapter 5: The Big Three

The Post-Joe Shuster Big Three: Wayne Boring, Al Plastino, and Curt Swan

Al Plastino was impressed with Wayne Boring’s art: “They gave me some of his pencils to ink early on. This helped give me a feeling of how Wayne drew Superman.” He occasionally saw the older man (born in 1905) in the art room at DC, though not too often, since most of the guys worked from home. The two artists got along fine. “Wayne had really tight pencils.”

Nevertheless, Plastino had mixed feelings while under his senior’s shadow. When he looked at “The Three Supermen from Krypton!” from Superman #65 (July–August 1950) from today’s perspective, Plastino noted: “That is crap, because I was still influenced by [him]. But at least you can follow the story. My faces were lousy, but they were consistent.” When asked why he broke from following Boring’s lead, Plastino said, “No one said change it. Wayne’s work was really clean cut and professional, though the characters were a little stiff. It almost hurt me to draw like him. I tried to keep the look consistent, but it gradually did change.”

Because Jack Schiff was handling Wayne Boring’s work, he was also Plastino’s first boss at DC Comics. The goal was to maintain Superman’s artistic continuity. “Jack was one of the editors for Superman. He was a mild guy, very shy and gentle, nothing like Mort Weisinger. Jack was not a good idea man, unlike Mort, who was a great idea man. He would just say, ‘Here is the story, Al.’ He wouldn’t give directions, per se. I started working with Mort a little later.”

Though he could not remember when their working relationship began in earnest, there exists a note for Plastino to call Weisinger regarding his preliminary cover for Superman #60. With an indicia dated September–October 1949, this means the artist and editor had dealings with each other no later than spring of that year.

In approximately 1951, fellow illustrator Curt Swan was getting terrible migraines from Weisinger’s frequent demands to correct the art by adding more detail. Weisinger also bullied the artists when he thought they weren’t giving him his money’s worth. Swan’s headaches went away when he began standing up to the editor. In the book Superman at Fifty! The Persistence of a Legend! (edited by Dennis Dooley and Gary Engle, Octavia Press, 1987), Swan is quoted: “I did speak briefly to Wayne Boring about it when I took over drawing the syndicated Superman strip in the late ’50s or early ’60s, a couple of years before they killed it. He knew how difficult Weisinger could be on the subject of Superman’s looks. ‘Just hang in there,’ Wayne told me, ‘and don’t take any s---.’”

Plastino had his own perspective when dealing with Weisinger, but the results were the same: “My attitude was, they’re not bosses, they’re editors. Wayne was on the way out; they were feeding him less and less work. He had the newspaper strip. Then Curt Swan took over [the dailies, but not the Sundays, for a few years]. There wasn’t as much of a difference between Curt Swan’s style and mine as there was between mine and Wayne Boring’s. Curt’s style was more realistic and calm. I added more jazz, where Curt’s was more kind and a little monotonous because he would have no big changes between panels. But he was a good artist.”

Plastino added that Swan was a nice guy he enjoyed conversing with when they happened to be visiting the DC offices at the same time. He felt that Swan doing only pencils — and not inking himself — helped lead to his early demise (Swan passed away in 1996). Plastino said that controlling both tasks kept him from working himself to death. One time, when Mort Weisinger asked him to let someone else embellish his pages, Plastino turned in such sketchy work that no one could find the line to ink. The idea was quickly dropped.

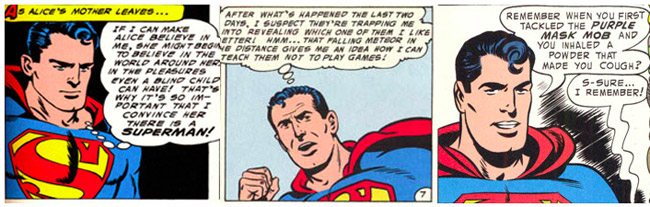

With much of Swan’s time monopolized by the syndicated dailies, and Boring’s by the Sundays, Plastino became Weisinger’s main artist on both Superman and Action Comics in the later 1950s. Superman’s writer-father, Jerry Siegel, found his way back to DC in 1959 to script the character’s exploits. About Siegel’s reappearance, Plastino said, “It was a terrible time. That Mort was a tough customer. He yelled at Siegel; he had him shaking in his boots. I said to Mort, ‘You wouldn’t have a job if not for him.’ When Weisinger had [Kurt] Schaffenberger redraw the heads on my Lois Lane a couple of times, he would tell me about it. He even wanted some of the money back that he paid me. I said, ‘Find somebody else.’ He started sputtering. I didn’t give a damn; you had to have that attitude. I got along with him after a while when I got huffy with him.”

Text ©Ed Zeno.