There’s real anger in that sequence. Is this anger mostly an expression of your feelings today, thinking about these events, or more the result of an effort to represent what you felt at the time?

The reflection is today’s… well, actually, it’s not, really – it dates back more than a dozen years, to when I was writing the first edition of the book, but I didn’t dare… I already had those thoughts then, and those sentiments, but I didn’t know how to express them, I didn’t know whether I could without risking a real scandal that might lead to legal problems. This was a real accusation, a defamation – I addressed the school: "you’re responsible, I accuse you." I didn’t have these thoughts right at the moment when I was living these events, but quite soon after that. So I decided to combine this analysis with the anger, which is really the anger I felt at the time. Back then, I got really, really, really upset with one of the professors: I cried, I screamed, I trembled with rage. It was so intense. I still have this anger today, but I’ve rationalized it much more… at the time, it was all I had, and the result was that I came across as a crazy person.

Authenticity

The reason I ask you is because of this notion of authenticity. This must be very important to you: here we have a synthesis of moments, something lived combined with certain ideas, and you must reconcile those while maintaining a sense of authenticity…

OK, so there are several levels of narration in this journal: there’s the author, Fabrice Neaud; there’s the narrator, Fabrice Neaud – he is the one that mostly expresses himself in the captions; and there’s the character Fabrice Neaud that you see in the panels. That’s three levels of narration. Ideas, concepts, analyses, rationalization are obviously made at a certain remove, in a present tense like that of Marcel Proust, by an omniscient narrator. But in order to stage the lived events of the time, I’ve decided occasionally to let the director talk through the character Fabrice, as in the scene with the professor. To stay true to the events themselves, I’ve decided to play myself as a different character and make him talk. That is to say, the angry character who talks doesn’t necessarily reflect the narrator’s thoughts.

Is it the voice of the narrator of the captions?

Those are closer to the thoughts of the author, my thoughts, than what happens in the speech balloons of the character Fabrice. I hope the reader sees the difference. I can draw myself very angry and add a caption that says "I was very angry" and it’s no longer the same thing. It means that the narrator of the caption is no longer angry, clearly. So I’m playing a bit with the narrative techniques of comics in those cases. In order to remain true to the events, I draw myself, but at the same time, I add commentary exterior to the lived events. Occasionally the boundary between the two is blurred, for example when the anger of then remains an anger of the now. That’s the case with the sequence on tolerance [toward the end of the book].

Ah yes.

There. It is clearly the narrator who is talking with an anger that is perhaps even stronger than that of the character. It’s a moment of synthesis of the two. We can no longer tell who is talking.

In that sequence you use symbolic images to talk about ideas and concepts, a little like David B. does so often, but also very different in that your drawing is so naturalistic.

Yeah, it’s a little like what Philippe Squarzoni does. We know each other well and he told me that he understood how one could express ideas and discourse in comics in this way from reading me…

Yes, comics are really well suited for that.

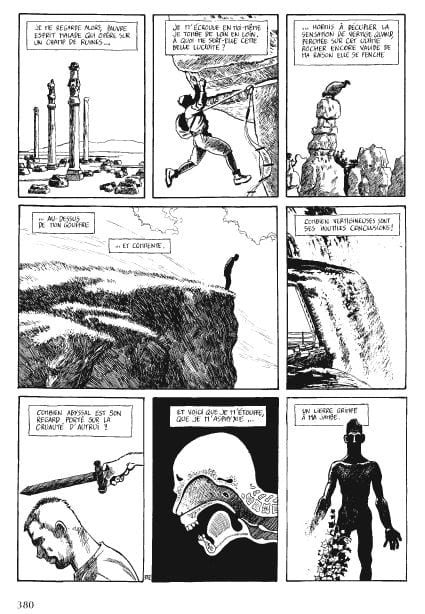

Exactly. You can put in a word, and an image that is like the word but has a different sense. For example, a little later in the book, after Dominique’s monologue, there’s this page, which has recently been analyzed by a semiologist from Lyon. He pointed out this part, where I write “So I look at myself, a stricken soul walking in a field of ruins”, and draw a field of ruins, but specifically ruins from antiquity. So there’s an interaction going on between the words and the image: the words by which I describe myself are a metaphor for feeling devastated, but at the same time I show antique ruins, which adds to the total meaning something else, namely the grandeur of an empire. The author, then, expresses a somewhat outsized opinion of himself: ‘I am a field of ruins, but I was an empire.’ Comics make that kind of thing immediately available, they’re great for that, because a word and a slightly displaced image changes or opens the total meaning in a very powerful way. In that whole sequence I try to work with that.

I also wanted to ask you about the choice to draw in this naturalist fashion. It’s very different from the work of many other autobiographical cartoonists, and because you talk about real events, it becomes a very clear choice on your part. You made this choice early on obviously – what were your thoughts?

It’s very difficult to answer that. Philippe Squarzoni has written an article on my work which answers that question, but I don’t quite recall all of it – it’s a very good article, very precise, and it’s going to be hard for me to explain, but yes, it’s a choice I made a long time ago and it makes all the difference. First of all, and very basically, I used to be a portrait painter and worked in a realist style, so I came to comics with a realist drawing style, based on observation from nature. That’s the basic explanation.

Beyond that, the choice to draw realistically… I’m going to have a hard time explaining it here, but I believe that only from a realistic starting point can you deconstruct your drawing. If you start out with symbolic drawing, you can play around with it like with Legos, you can put it together in different ways, but you can’t move back toward realism. If you create a very cartoony character, like Tintin, you can’t ever draw his face realistically. It doesn’t work. Hergé had this problem: I’m thinking in particular of that spread where he has, I no longer remember which character opening a newspaper, and on that page there is a close-up view of what he is reading, and his thumbs are drawn in very large and very realistically, and it just doesn’t work.

It’s what – using terminology borrowed from photography – I call the problem of going from high resolution to low resolution. If you take a photo of someone far away, someone unclearly defined, very pixelated, you can’t then enlarge the image of that person and make it clear; you can only loose definition. So, in order to give the illusion of deconstruction in drawing the widest possible expressive field, you have to start out with as realistic a style of drawing as possible, then all the levels below that are accessible. Once you’ve degraded, you can’t go back to high definition. With the exception, perhaps, of works like Maus: when you’re evoking very powerful historical events, I think you can make it work by drawing them in a rather minimalist manner and then at some point inserting photographs of the reality depicted, which allow an expanded understanding on the part of the reader.

Doesn’t this high resolution basis present its own problems? If we compare again with David B. and his “low resolution” style, he utilizes it to draw a world of symbols, to draw his consciousness, and he maintains a strict coherence, or stability, in his imagery. On the other hand, if you start out with a realist style and want to do something symbolical, isn’t there a risk of getting caught up in the forms and textures of the physical world?

It’s a risk. For each page, I ask myself whether I want to break with my basic style. I think that on certain pages, especially in volume 4, it doesn’t work. It’s a very real problem. But at the same time, I will always defend this precise, realist style because, as I said, it comes from portraiture, and I know this is very subjective, but for me it’s important to be able in my comics to go as far as possible in showing the reader an embodied experience – to show really subtle nuance, to suggest the erotic, the desire inspired by a certain pair of ears for example, or a neck… of course, one can also do this in other ways, drawing in a different style. Chris Ware, for example, in Jimmy Corrigan manages, even with his very stylized drawing, to show skin impurities… the doctor who examines Jimmy; there’s a panel just of his mouth which is really gross. That works.

Ineffable desire

It is clear that sensuality is very, very important in your drawing.

What’s important to me is embodiment. There are ideas and concepts, but what I have to tell isn’t just that.

No, it’s physical.

It’s physical, it’s embodied; that’s also my life and I limit the reader’s liberty by imposing upon her or him very precisely portrayals of my desire. People often say, "you like strong, buff guys wit short hair, etc.," but what really interests me are the small differences between two strong, buff guys with short hair that might on first glance appear the same. The scene with the sergeant; when I had to draw that, I wondered who I was going to use as a model for him, and I ended up using three different guys. Somebody who isn’t attuned to that won’t see the difference – "a buff guy is a buff guy," they’ll say, like a racist would say "a black is a black" or "all Japanese look the same." I want to show that despite everything, each of these people has a very particular identity, and it is only by drawing very realistically that I can do that. At a few points in the book, I draw a guy that looks like Dominique, and the way I draw makes you, the reader, doubt whether it is indeed him or not, until I tell you, because you’ve gotten used to see Dominique as I draw him.

Yes, that wouldn’t be possible with photographs, but in comics…

Yes, exactly, in comics you can play with the information conveyed by an image; I also explore that with numbers: three-six-nine – those are multiples, but they’re also different numbers, and I use that device… I don’t know whether it’s clear or not, really, sometimes, but I use that device to put across that what’s important to me in my desire is the tiny, tiny, microscopic variations in a face that, I think for all of us, trigger our desire. I mean, you’re attracted to someone, you don’t know why, and at the same time, someone else who resembles him won’t necessarily be attractive to you. Desire emerges in the ineffable particularity of a face.