In 1870, Paris was sophistication's world capital. Its boulevards were filled by elegant cafés, its shop windows sparkled and its food was famous. It had pioneering networks of sewers and streetlights, a market in luxury goods – and cartoonists just as well-known as its courtesans. It had given the world Baudelaire's poetry, Edouard Manet's paintings and, with Charles Frederick Worth, the first haute couture.

But it was also a capital of repression, one that worked hard to hide huge inequalities. Those celebrity satirists were monitored by police and surveillance was a fact of almost everyone's life. Censorship of French cartoons was, as Robert Goldstein notes, "eliminated in 1814, restored in 1820, abandoned again in 1830, re-established in 1835, ended once more in 1848, re-imposed in 1852, abolished in 1870, decreed once more in 1871 and finally ended… [only] in 1881."

In autumn of 1870, however, everything changed. That summer, the French Emperor Napoleon III declared war on Prussia. Bourgeois society's support for his foolhardy act was sweeping. Yet, by September, the Emperor was a prisoner and Paris found herself encircled by the Prussian army. They were also at war with something else: smallpox.

The Siege of Paris lasted five months, during which "normal life" totally disappeared. While rich Parisians fled, war refugees and poor from the suburbs flooded the city. Over 120,000 soldiers were mustered to hold off the Prussians. But, as the French Academy of Medicine mourned, "These soldiers and travelers spread the smallpox everywhere".

Calculated according to a faulty census, the city's stockpile of supplies gave out in a month. The residents were then forced to manage on meagre rations with the middle class eating first cows, then horses, then dogs. Municipal kitchens struggled to feed the poor, using soup and "brown bread" made out of flour, straw and vetch. The truly desperate scavenged for rats and burned stolen shutters for heat. Once local cows and horses had been slaughtered, there was no public transport and the children lacked milk. Suddenly, for even the wealthy, grapes and gruyere were nothing but a memory. When Victor Hugo, one of the world's great celebrities, received a small gruyere for New Year's Eve, he called it "a miracle".

The only things in plentiful supply were wine and absinthe – a fact that, of course, caused special problems.

Paris tried frantically to reconnect with the world. Letters, papers and homing pigeons (even politicians) left the city by hot-air balloon. Around their legs, the birds carried letters on microfilm. But since gas was needed to power these vehicles, all the street-lights had to be doused. The elegant trees along the boulevards vanished, too. Like those in parks, they were razed for fuel. By five p.m., the city became dark and claustrophobic. Temperatures fell (eventually, to minus ten) and the river Seine froze. All these conditions helped spread the smallpox. So did the piles of filth which soon appeared everywhere. Those "essential workers" who had kept the sewers running were Prussian – and they had left.

From early January, Paris was also bombarded. Terrified and demoralized, residents tried to shelter in basements. Yet when their leaders finally did surrender, many opposed ceding their city. They declared a separate Paris Commune – and the capital then suffered a second siege by their own army. It became a civil war, with thousands murdered in the streets and landmarks burned to the ground. "Fifty Thousand Dead Bodies in Houses and Cellars", the New York Times recorded. "One-Fourth of the City Destroyed by Flames".

The Commune, still controversial, passed into legend. Yet the five-month Siege – and, certainly, its epidemic – are remembered with only a couple of tales. One is that of French foodies forced to eat their zoo. The other is their postal service based on birds and balloons. Yet something else helped those besieged Parisians cope and that was the mordant art of a few cartoonists.

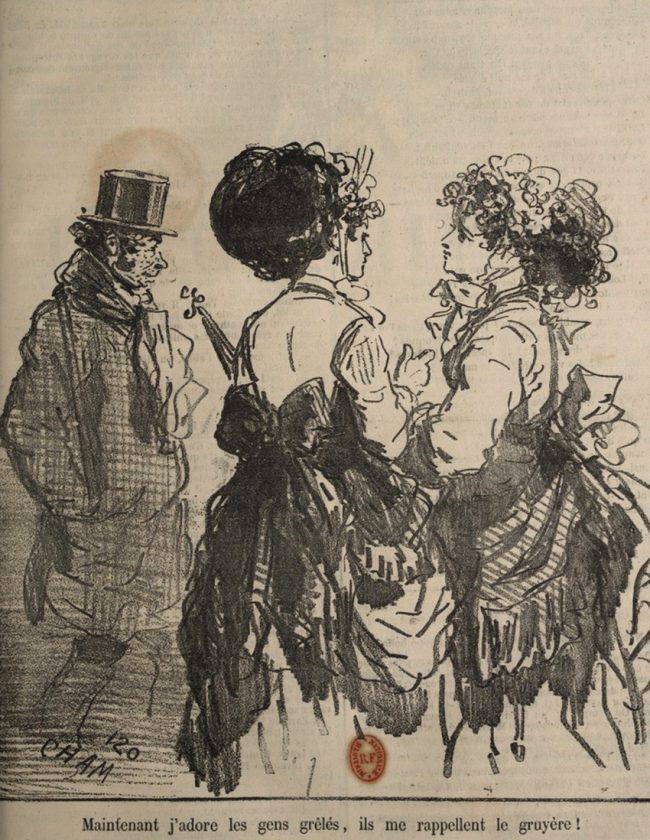

Their moment is summed up in a cartoon by Cham (Count Amedée de Noé) which appeared November 27, 1870 in Le Charivari. It shows a male smallpox survivor passing by two women, his face covered in tell-tale scars. One of the ladies whispers to the other, "These days, I love the pockmarked people. They remind me of gruyere." The sketch seems puzzling now, because the epidemic is forgotten.

Yet, even before the war, smallpox had been terrifying rural France. It forced the writer George Sand to flee her own chateau – something well understood by her pal Flaubert, who was hundreds of miles away. Smallpox, he wrote Sand, had just killed his housemaid. The death toll grew so alarming that, right before the war, Paris held its first-ever emergency medical conference. Doctors came from all around the country.

The plan they tried to architect failed miserably. As one medical history notes, the smallpox "raged more extensively and furiously than any other epidemic in the course of the entire century, spreading… throughout all Europe." Within a year it reached America and, from there, Asia.

Dr. Victor Aud'houi, 29, was among the locked-in Parisians. The smallpox he treated, he writes, was hemorrhagic. This meant it started with a single pustule that proliferated until the skin was covered. ("The whole body surface appears a single bluish red, very like the color of wine… Blood drains by every route and… even the gums can hemorrhage.") Within ten days, almost every patient died.

The medical star Louis Pasteur had tried to sound an alarm. But, even for a celebrity, it was uphill work. Back in 1805, the pioneering Napoleon had his army vaccinated. But, as the decades passed, concern about smallpox declined. Technically, Army vaccinations were required but they soon began to lack close policing. If a first vaccination failed to "take", a soldier received no other. Plus, when 1870's Army rallied 600,000 men, they did it quickly – outside the rules.

Pockmarked skins were a frequent sight in the street, yet many French citizens scorned vaccination. For years, too, it had been the butt of cartoons. Paris' famous Depeuille print works issued many series of these, often showing its advocates as "profiteers". By the Siege, over 40% of French children – just like their parents – lacked such protection.

The result was 89,000 deaths within a year, 10,331 of which took place in Paris.

The 1870 version of a "coronavirus diary" was the "Siege journal". Countless Parisians kept these and some are still in print. The traumas of the whole event – hunger, bombardment and the city's mutilation – were so inconceivable they write little about the smallpox. Yet, it you look, it's always there. On January 9, for instance, Jacques-Henry Paradis – a middle-aged stockbroker – made his nightly entry. During the record-breaking week just ended, he writes, 3,280 Parisians had died. This was "400 more than last week … almost all of them additional smallpox victims". A fortnight later, Paradis again noted exceptional mortality stats. This time, there were 4,465 with a rise of 380 in those from smallpox.

Cham's cartoon encapsulates this whole ordeal. But the fact that he joked about an epidemic as it happened isn't too surprising. Always irreverent and incisive, Amedée de Noé was an unusual figure. He matters as much to the history of the comic strip as he does to that of caricature.

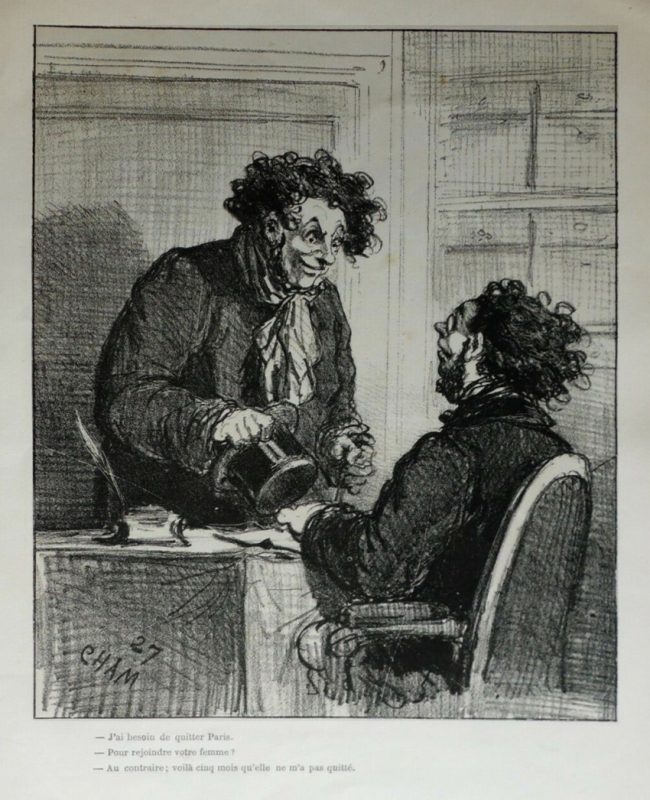

Thanks to David Kunzle's excellent new Cham, de Noé is finally now getting his due. As Kunzle shows, Cham was hugely versatile and availed himself of many different formats. He brought the same inventiveness to telling tales in sequential frames, related vignettes on a single page or in – one of his trademarks – cheap and topical "albums for a franc". But Cham was just as happy drawing full-page cartoons for Le Charivari. There, by 1870, he was the star artist. Prolific, original and eccentric, Cham was a nobleman who married a servant; an early (and ferocious) champion of animal rights; the semi-royalist star of a staunchly republican journal.

Above all else, he was a sharp-eyed observer. Cham himself had made fun of vaccination in 1840, when he called an album Deux Vielles Filles vaccinées à marier, "Two Old Maids, Vaccinated for Marriage-Readiness ". (That story, striking for its graphic dynamism, can be read here.) Kunzle calls Cham "a graphic journalist…[something which] requires constant alertness and great inventiveness. Cham liked to deliver multiple takes, run circles around the topics of the day, to ring the changes, put all of Paris in the arena and campanile of his pen."

By the time of the Siege, however, he and his famous colleagues at the Charivari – Honoré Daumier, Paul Gavarni (Sulpice-Guillaume Chevalier), and Bertall (Charles Constant Albert Nicolas Viscount of Arnoux) – were the old-school stalwarts of a well-established paper. All were fifty or older; Gavarni was 66 and Daumier, who was losing his eyesight, 62. A younger generation had risen to prominence, many through the anti-establishment weekly L'Eclipse.

Two such Eclipse artists were Paul Hadol, 35, and "Draner" (the reversibly-spelled nom de plume of Jules-Joseph Charles Renard, 37). Renard was Belgian, a businessman who had moved to Paris to become a cartoonist. Work at L'Eclipse led both Draner and Hadol to Le Charivari.

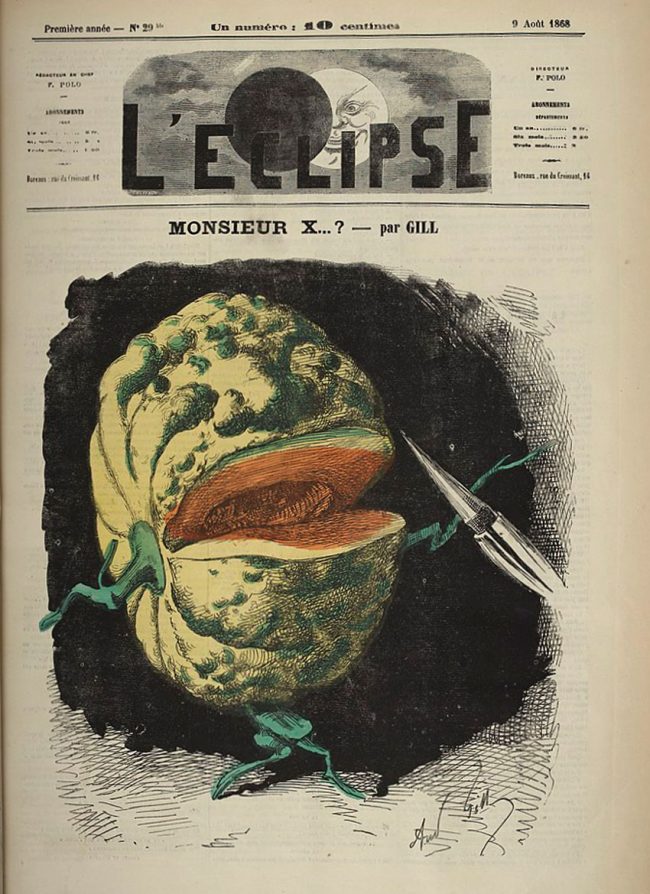

L'Eclipse, however, had its own superstar: the thirty year-old bohemian André Gill. By 1870, Gill too was one of Paris' favourite artists. But between September 4 and the Commune, L'Eclipse ceased publishing and he drew almost nothing.[1] Just before the Siege, however, L'Eclipse had absorbed another journal: La Charge. La Charge, even more ferocious, was edited by a 29 year-old, Alfred Le Petit.

Le Petit would keep cartooning through the lockdown, often billing his prints as "supplements to La Charge."

Alfred Le Petit was infamous for taunting the Emperor. La Charge often published his art without prior approval and, on many occasions, cartoons were barred or seized. But when he depicted Bonaparte as a pig (the animal's back was turned but the inference was clear), all hell broke loose. The whole print run was confiscated and burnt while Le Petit was fined 500 francs and sentenced to jail. Only the Emperor's fall saved him from prison.

A colleague who did do time was Georges Pilotelle ("Pilotell"), 25. At La Lune, the journal which had first made Gill a star, Pilotell functioned as an understudy. If the laidback Gill happened to miss a deadline, Georges was relied upon to dash off a cover. Pilotell's Siege cartoons were famous for their buxom ladies.

During 1865, for "press offences", Pilotelle was sent to jail in Sainte-Pélagie prison. For opposition artists this was a tradition; the spot had been consecrated by the likes of Charles Philipon and Daumier. (Even during the Revolution, Sainte-Pélagie had housed celebrities.)[2]. Pilotell was also jailed in May of 1869 and for two additional months that October. Although he became a fervent Commune activist, the artist escaped its bloodshed to settle in London.

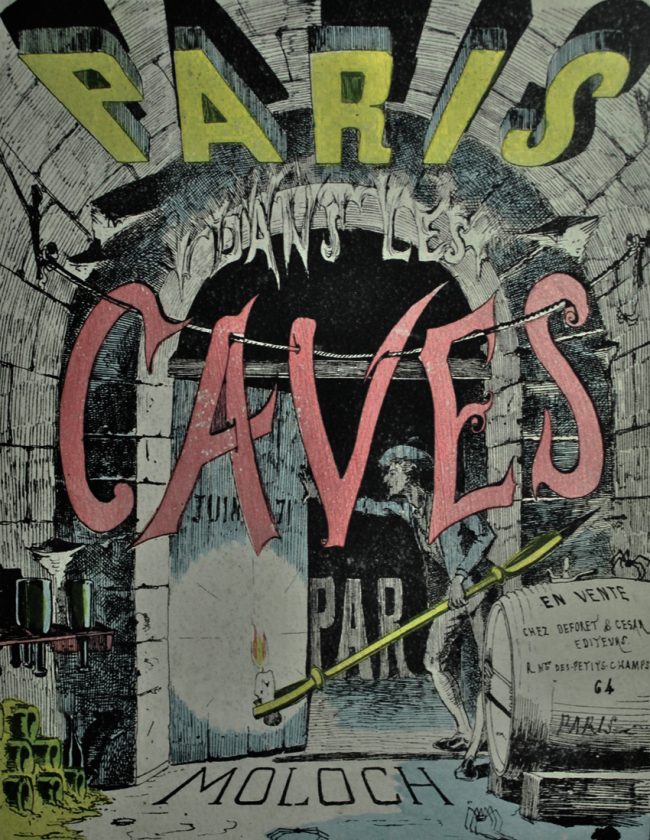

The real comic stars of the Siege were, however, younger. They were the trio "Faustin" (Faustin Betbeder, 23), "Moloch" (Alphonse Hector Colomb, 21) and "Frondas" (Napoleon Charles Louis de Frondat, 24). Evaluating their work fifty years later, French historian Henri d'Alméras found it outrageous. "From the priest's cassock to the judge's robe, these caricatures respect absolutely nothing. They encouraged people to scorn the establishment and, in their way, contributed to the civil war".

But for cartoonists like them everything had changed. The end of the Emperor's reign, combined with the unexpected Siege, produced a situation that would never be repeated. Forty-eight new papers started in this tumultuous era, few of which were satirical. Most of the humor journals ceased publication – although the daily Charivari, with Cham, Daumier, Faustin and Draner, managed to appear more often than not.

Despite the lack of outlets, cartoonists were now totally free, albeit in a situation they could not have imagined. Most of their responses to the Siege were "tirages à part": loose single sheets displayed on the newsstands. Although ephemeral, they were often conceived as series and many duly appeared later, as "souvenirs". The sets had titles such as Les Assiégés de Paris ("Parisians Under Siege"), Paris Bloqué ("Paris Paralysed") or Actualités ("Newsflashes"). The publisher Grognet's Actualités totals 87 prints and it employed a host of creators. Some of those artists, like "De la Tremblais", are now little more than a signature. Although De la Tremblais worked through the Commune, it seems likely that he died in the fighting. Others, like Swiss-born Paul Klenck, 26, left a vivid if now scattered legacy.

Henry Vizetelly was the Illustrated London News' Paris correspondent. Vizetelly stayed in the capital until November, when most foreign residents were allowed to leave. He was amazed at how cartoons invaded the city: "… Some very droll designs were published in the Charivari… But the caricatures in comic journals were only a fraction of those which appeared. Scores and scores were issued separately at a penny each, displayed at the kiosques on the boulevards or being strung, like clothes, on a line running from tree to tree. Many of them were decidedly offensive to public decency…".

By night, on the darkened boulevards, they were peddled by hawkers.

At first, Siege cartoons lambasted the Prussians and mocked the former Emperor. But they soon moved on to criticizing his successor: the hastily-assembled "Government of National Defence". All of them shared a new audaciousness – one that was frequently scatological or obscene. Many were influenced by Paul Hadol's La Ménagerie impériale, composée des ruminants, amphibies, carnivores et autres budgétivores qui ont dévoré la France pendant 20 ans (The Imperial Menagerie: the cud-chewers, amphibians, carnivores and other budget-feeders who devoured France for 20 years). Begun between Napoleon's fall and the Siege, this was a series of more than thirty prints. Each lampooned someone central to the Empire, marrying a familiar head to a zoomorphic body.

Unlike most Siege cartoons, Hadol's collection is celebrated. "While caricature is hardly a measured art," writes academic Alain Galoin, "the Ménagerie displays a rare cruelty… Its cartoons are a visual synthesis of just how much opprobrium descended on the idea of Napoleon III's reign once it had fallen."

The anger in such drawings had built for two decades and it embraced more than military disgrace. It was a response to centuries of censorship, to corruption and failed reform, to foiled revolutions – even to the demolitions Baron Haussmann's re-design had forced on Parisians. This no holds were barred. Faustin, for instance, shows the Emperor – who had well-known kidney problems – incapable of pissing his own caricature off a Prussian helmet. Under the pseudonym "Cambronne", he also drew Napoleon, Bismarck and Wilhelm I as a huge spiralling turd, with the caption "A bunch of… rascals !!!". Above this image appear the words "To the Prussians, who can count on us giving them 9,679,111": a mystery it took more than a century to decode. It was the art historian Thomas Schlesser who noticed that, in a mirror, Faustin's "9,679,111" becomes the word "merde" ("shit").

The Empire's "decadence" informs countless caricatures, with Napoleon and his Empress attacked as viciously as Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI. (Empress Eugénie, often nude, is shown as a nymphomaniac – exactly as the guillotined queen had been.) Many such drawings, like Hadol's La Grue ("The Whore") or Faustin's Deux Dames, juxtapose her with a tambourine. Partly this is a mockery of Eugénie's "foreign roots"; she was born Eugénie de Montijo, in Grenada. But it also references the now-archaic pornographic verb "tambouriner".

Many of those cartoons call the Emperor 'Badinguet', a false name once used by Napoleon III. This moniker, which he supposedly stole from a mason, also belonged to a famous Parisian clown. Many sketches parody Napoleon's womanizing and his self-indulgence – there's no longer any problem drawing him as a pig. Faustin's ex-Emperor appears as a drunken swine, staggering on hind legs down a seedy alley. De la Tremblais offers up the Bonaparte dynasty as "Charcuterie": cold cuts with human heads, each available for a price.

Such cartoons were incredibly popular. Faustin told a friend that, in 24 hours, one of his prints sold 61,000 copies. Yet the whole phenomenon was almost lost to history. Many of the actual prints, like much of what is known about them, came from just one man. This was the politician and novelist Maurice Quentin-Bauchart (1857 – 1910). Starting eight years after the fall of the Commune fell, Quentin-Bauchart tried to assemble every print made during the era. A decade later, under his pseudonym Jean Berleux, he published the catalogue La Caricature en France pendant la guerre, le siege de Paris et la Commune. The pieces it lists are rarely shown together, although you can see some at Saint-Dénis' Musée d'Art et d'Histoire Paul Eluard. But many are now digitized and the British Library holds two bound volumes of them. These were also assembled by a collector – London-based bookseller Frédéric Justen – who donated them in 1889.

Even such contemporary fans felt the cartoons were scandalous. In the introduction to his own index, Quentin-Bauchart complains that "in this phenomenal explosion… few truly merit the mantle of caricaturist". Many of the artists, he concedes, are funny yet even those he likes go too far for him. Quentin-Bauchart hammers Paul Klenck for "grubby flights of fancy", Moloch for "vulgarity" and the prolific Faustin and Frondas for "near-obscenity". His real respect goes to the old guard: Cham and Daumier, Draner and Bertall.

The artists' more traditional contemporaries were just as shocked. Catholic journalist Louis Veuillot made a public complaint to the government. "A vomiting of caricature begrimes our city," he railed, "… Never has anything seemed more sordid, barbaric or bestial. It's bloodthirsty and obscene, repulsive in its stupidities… It's like some abject convict, a recidivist jailed for rape, scratching on the wall of his cell with a stolen nail.

But one 16 year-old fan disagreed. During February of 1871, Arthur Rimbaud ran away from home and, for two weeks, bummed around Paris. Rimbaud was a long-time reader of La Charge and he had even sent the paper one of his poems. As "Trois Baisers" ("Three Kisses"), this appeared in their issue of August 13, 1870. Rimbaud always followed the work of Alfred Le Petit, André Gill, Draner, Gustave Doré and Alfred Grévin (later the founder of Paris' wax museum). Writing his friend Paul Demeny in April, Rimbaud recalls what he saw in Paris. His eye was "especially" caught, he says, by the cartoons of Draner and Faustin.

The Second Empire reshaped more than just the physical Paris; it also altered mainstream culture. Under Napoleon III, French society was composed of winners and losers, inhabitants of a ruthless, consumer-driven meritocracy. Its bourgeoisie preferred, notes historian Robert Gildea, being entertained to being challenged. The bodily and psychological sufferings of the Siege upended years of the Empire's formulae. This suddenly "upside-down" world was the basis for countless jokes.

"The Edibles" from Paris Assiégé by Draner, 1870

Many of them focused on the frenzied search for meats. Draner's print "The Edibles" shows a loyal family dog looking up at the paunch of his middle-class owner. (His wife, in the background, dabs at her eyes). "My poor Fido," the man is saying, "For self-preservation, your master must devour you". The fact that both he and his wife remain quite plump adds a special bit of black humour.

Some of this genre's most popular jokes came from Cham, whose beloved poodle Bijou shared his celebrity. (When Bijou sickened and died in the Siege, the artist made sure he was safely buried in the garden). One Cham cartoon warns viewers against dining on mice, lest some hungry cat leap down their throats in pursuit. At the famine's height, he shows a man whose stomach hurts "because he ate dog on top of cat and, of course, they disagreed". With queues for rationed meat filling every street, Cham sketched Parisians shamelessly prone and peering into gutters, hoping for rats.

Siege cartoonists also reveled in bawdy double-entendres. Draner, for instance, shows a soldier trying to charm milk for his coffee out of a breast-feeding wet-nurse. Allusions to cannibalism were a constant and many linked female flesh with the longed-for "dishes". Key to such jokes was a slang in which terms for food often bore lewd connotations. Outside of the kitchen, words such as viande (meat), bifteck (beefsteak) and casserole (saucepan) were terms that referred to the world of prostitution. In the Army, bifteck à corbeau ("steak for the crows") meant rotten meat. But it could also indicate an over-the-hill whore. A laitue (lettuce) or a chouette (owl) was a fresh young prostitute, but veau (veal) was young flesh that carried a sexual disease.

Countless culinary terms had double meanings. A biche was a female deer – but also a kept woman. A crevette (shrimp) was a common streetwalker. Harengs (herrings) and maquereaux (mackerels) were pimps, while terms like bonbon (candy) and chatte (cat) meant the female genitals. "Cake", from the English, denoted an "ugly mug": one whose skin had the stigmata of smallpox.

A "marron" was a chestnut. But it could also mean a punch to the face – or someone caught out, someone whose "goose was cooked". The series Marrons Sculptés, drawn by Frondas, unites all three meanings. Charles De Frondat, who signed himself "Frondas", "Juvenal" and "Japhet", clerked at a local town hall. After the Commune, he meekly rejoined the city's civil service. But, in between, something happened and de Frondat exploded into constant, caustic cartooning. He even published a journal, La Puce en Colère ("The Angry Flea"). It lasted just four issues.

From January 5, the Prussians shelled Paris. Although there were substantial injuries, actual deaths were few – probably around sixty. Yet, as Jacque Paradis laments in his diary, 4,000 souls a week were being lost to illness.

Graphic artists worked to boost their fellow citizens' courage. Among them was caricaturist Albert Robida, 22. Although fully devoted to soldiering, Robida kept a lively sketchbook. In this, he captured citizens at the city's edge – paying soldiers to let them "view" the enemy's guns. Another artist who helped aid morale was Gustave Doré. Doré, now 38, had begun as one of Philipon's protégés. But, by 1870, he was a well-known illustrator. During the Siege, his patriotic drawings made him what critic Hollis Clayson calls "the leading specialist in bombardment imagery".

Some of Doré's sketches were sent by balloon to England. There they graced the Illustrated London News. But while such work was sober and reportorial, the new cartoonists had spicy fun with the protective cellars. Two, Frondas and Moloch, focused on their "secrets" – i.e. the opportunities for hanky-panky. Frondas draws guardsmen holding trysts in sentry huts, basements and while "sheltering" under bunks. His prints were later published as Paris guard national: Souvenir de deux sièges ("The Paris National Guard, A Memory of the Double Siege"). Moloch's best-selling series was Paris dans les Caves ("Paris in the Basements"). It features everything from fart jokes to rats who invade cellar cocktail parties.

Morbid humor was a staple of such cartoons. In one Moloch print, two returning husbands find their hungry wives are now headless corpses. "You fool!" cries one of them, "I told you we must never leave those two alone!" In a different sketch, a plump man goes green as his emaciated cohort pronounces him the "sacrifice" for dinner that night. ("But… you are free to choose whatever sauce will suit you…").

Moloch also shows a gent whose friends discover him covered in sprouting mushrooms. As they recoil, fearing smallpox pustules, he attempts to explain. "But I tried to tell you! It really is humid down here!").

Cartoonists were just as hungry as anyone else and, before long, they began to draw people as vegetables. Faustin showed a stylish carrot meeting a poor potato, the latter dressed in its rough burlap sack. Drawings featured politicians as beets who blushed for their sins, leeks wilting under pressure and mushrooms who could now flourish, thanks to the city's filth.

Back in 1846 with Les Fleurs animées ("Flowers Personified"), J.J. Grandville made such animations wildly popular. But two fruits were also iconic in French caricature. One was its famous pear, the symbol used by La Caricature to torture Louis-Philippe during the 1830s. The other, much more recent, was André Gill's melon.

Eighteen months before the city's Siege, Gill had bought an especially luscious melon. But before enjoying it with some pals – one of them future Communard Jules Vallès – the artist cut himself a crescent-shaped piece to taste. He then set about sketching the gourd in front of his friends. Gill turned the fruit into a chubby figure with an open mouth, fleeing his pen. Even without a subject, he boasted, it would make L'Eclipse a provocative cover.

The artist won his bet. Captioned "Monsieur X…?", his melon appeared August 3, 1868. The whole city argued and fought over who was its target. Was the melon a portrait of some magistrate? Was it a religious zealot? Or the Emperor himself? The censor, just as confused as everyone else, had to settle for condemning it as "obscene". Gill succeeded in talking down this charge in court, but L'Eclipse was heavily fined. As it had with Philipon's pear 34 years before, this tactic backfired. Street hawkers sold the reprinted cover for a premium, censorship's authority was weakened – and Gill's cheek was celebrated all over Paris.

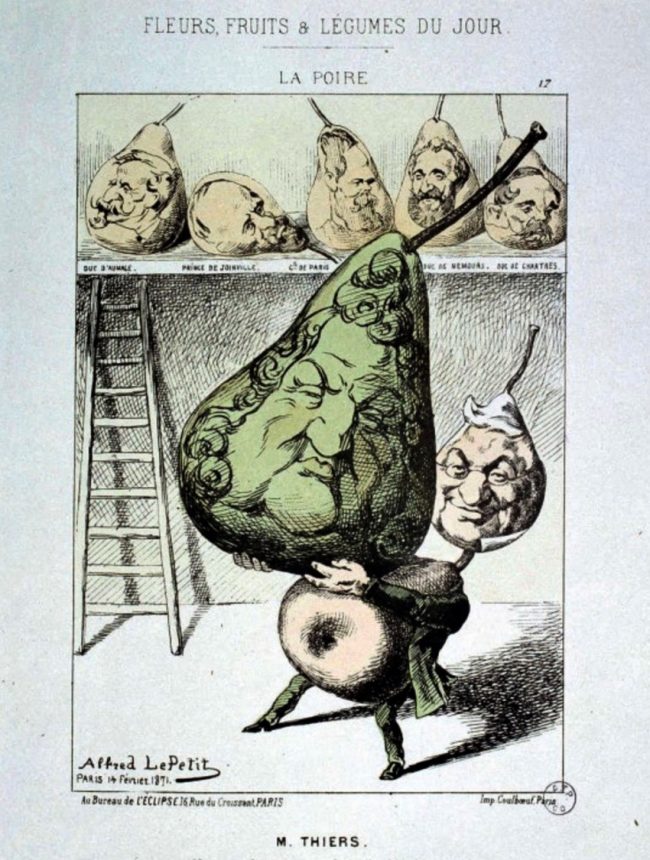

During the Siege, Alfred LePetit leapt into this vegetable breach. Between January and March of 1871 – the final days of the first siege and the start of the second – he and humorist Hippolyte Briollet created a series called Fleurs, fruits et légumes du jour ("Flowers, Fruits and Vegetables of the Day"). They did it at a moment of lethal civic chaos.

On January 18, in Louis XIV's Versailles, Prussia's Wilhelm I proclaimed the new German Empire. The Germans agreed not to occupy Paris nor disarm her National Guard. But they did insist on a victory parade through the city. Adolph Thiers, who had faithfully served caricature's enemy Louis-Philippe, was made head of the new French government.

Thiers revealed his loyalties immediately. He ended a freeze on rents and commercial loan payments that had been in place throughout the Siege. He then announced everything not repossessed from the city pawn shop would be sold. This civic moneylender, the Mont-de-Piété, served the city's poor as a bank. Besieged Parisians had deposited countless items there, from 3,000 mattresses to 1,500 pairs of scissors. No-one had the money to buy back such possessions.

The final straw was Thiers' decision to reclaim the cannon – bought with public pennies – which had defended Paris. This detonated so much anger the government had to flee their capital. They decamped to Versailles, where they were joined by most of the privileged.

While they served, the Paris National Guard had not risked starvation. Their rations were more robust than those scrounged up for civilians and each man received 1.50 francs per day. Cham had mocked such officers for "requisitioning" food in the streets. Now, however, the government put an end to their stipend – and with it went the sole support of many families.

On March 18, the capital exploded; ten days later, it declared the Commune. This radical effort at self-government lasted only ten weeks.[3] On May 21, the Versailles army stormed back into town. Many of its soldiers, trained by colonial wars in Mexico and Algeria, saw the Parisian working class as savages. Their advance initiated the notorious Semaine Sanglante or "Bloody Week": day after day of organized murders and killings. Atrocities occurred on both sides of the fight and, as they retreated, the Communards lit a wall of flame for protection. While much of central Paris blazed, working-class men, women and children were summarily executed by the "Versaillais". French men and women massacred one another in what some have termed a political holocaust.

Even by today's most conservative estimate, more than 13,000 people perished. (In one report, the government tallied its executions at 15,000; in another, 17,000.) But many sources figure higher casualties, somewhere between 30,000 and 35,000. Mercy was rarely shown nor was there was aid for the wounded. Thanks to the epidemic's 6,000 patients, Paris' hospitals were already overwhelmed.

Fleurs, fruits et légumes captures the tragedy's major players. Without its context, of course, the portraits lose their meaning. Yet because they use every possible vegetal state – from pulpy to wizened, succulent to rotten– Le Petit's visuals still have an eerie magnetism. Says critic Bertrand Tillier, "As he revisits the whole political class, Le Petit gives his series a self-enclosed hierarchy … he moves through every strata from roots and tubers right up to the seed-bearing plants…his portraits contrast beauty with ugliness, play the subterranean off against the aerial and juxtapose the shady with the illuminating..."

The Commune's brief life produced its own caricatures. But Fleurs, fruits et légumes marks the apex of Siege cartooning. It captures that eruption of excess and regression which foretold, not regime change, but a total bloodbath. The Paris that produced it suffered as much as did its citizens. Photographs of Communard barricades were succeeded by unthinkable images of posed corpses and burnt-out palaces. When the city re-opened, these bought Paris a wave of disaster tourism.

One who visited was Gustave Flaubert. Arriving from the safety of his home in Normandy, the writer was appalled. "The odour of the corpses," he wrote George Sand, "disgusts me less than the swamps of egotism.… Half the population wants to strangle the other and that half is happy to reciprocate the sentiment. You can read it clearly in the faces of every passer-by.… It's enough to make one despair of the human species."

Paris stayed under martial law for five more years.

The codes of Le Petit's Fleurs, fruits et légumes endured. Two decades later, the artist would reprise its schema, although he left his second series unfinished. But take just one example from 1871: Le Petit's print Le Raisin ("The Grape"), which appeared on February 9, 1871. This portrays the radical Henri de Rochefort, who was close friends with Cham. Just like Cham, born a noble. He was not an artist but a radical pamphleteer and an author of vaudeville comedies. Rochefort was also well-known for his bon-mots. In 1868, he had famously quipped, "According to our Almanac, France has 36 million subjects. But that's not counting all the subjects of her discontent."

Le Petit shows Rochefort's head, over four frames, becoming a bunch of grapes. It's an echo of Philipon's famous sketch: King Louis-Philippe morphing into the pear. Philipon's lèse-majesté got thirteen months in Sainte-Pélagie – and Rochefort had languished for six at the same address. But now, asserts this portrait, the tables are turning. Le Petit shows Rochefort's hair, his trademark, blossoming into fresh green leaves.

Briollet's caption hails the activist as "A bunch of grapes whose berries give us wine that is clear, red and copious". These are words meant to evoke an agitator's eloquence, his lucidity – and his righteousness. But the link to red wine was hardly innocuous. As Jean-Pierre Azéma and Michel Winock write in Les Communards, red wine was the symbol of a radical working-class. "So obsessive was the link in the Versaillais mind between red wine and red politics, that their Army thrust the necks of wine bottles into the mouths of corpses. They pinned signs that read Ivrogne ("Wino") on their chests".

"Le Petit's grape comparison," notes the Musée de Poitou-Charentes, "also works because of its model's recognizable visage, which is bony and bears the scars of smallpox." Did Rochefort sicken during in the Siege epidemic – or did he bear the marks of some earlier bout? There's a famous set of Communard photos, annotated by the Interior Ministry's Edmond Louis de Nervaux. The back of Rochefort's photo by Ernest Appert notes, "Tall with curly dark hair, dark beard and a pale complexion with the marks of smallpox". When Edouard Manet did Rochefort's portrait, visitors who saw it at the Paris Salon were shocked. Shuddered the rich American collector Louisine Havemeyer, "One visitor remarked that Manet painted Rochefort as if he had smallpox."

This was the Paris Salon of 1881. But memories of the smallpox were vivid, not least thanks to Emile Zola's Nana. This scandalous novel, published the year before, starred a courtesan who symbolized the Second Empire. Nana dies of smallpox, expiring while crowds around her home cheer the Emperor's war. She is all alone, her once-adored face now "a mass of blood and matter, a heap of putrid flesh shoveled onto a pillow … the shapeless pulp whose features had now entirely vanished resembled nothing more than the greying mould on a grave." This description, which continues in gory detail, is often now considered a metaphor for moral decay. But it was really neither quite so neat or so abstract.

Nana (1880) and Manet's portrait (1881) bracket the tenth anniversary of the Siege. This long-forgotten moment, with its pandemic, isolation and climactic carnage, was so singular its humor is uniquely cutting. Many of the artists' stories have vanished, yet their contribution to French cartooning endures. They helped consolidate its nerve, its demand to be heard – and the stubbornness behind its resilience.

***

- I highly recommend David Kunzle's new Cham : The Best Comic Strips and Graphic Novelettes, 1839-1862 (University of Mississippi Press). It's erudite but readable, with great reproductions. Although it's pricey there is a less expensive copy for Kindle. I don't usually recommend Kindle but this is worth it. For anyone interested in the Paris Commune, John Merriman's Massacre (Yale University Press, 2014) is also great.

- Special thanks to online services at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the British Library, Labibliothèque interuniversitaire de santé, the Wellcome Library and Maurice-Quentin Bauchart's La Caricature Politique en France pendant La Guerre, Le Siège de Paris et La Commune (BnF). Also Hollis Clayson's Paris in Despair (University of Chicago Press, 2002); Bertrand Tillier's La Républicature: La caricature politique en France, 1870-1914 (CNRS Éditions 1997); Allison Deutsch's War, Revolution and the Butcher Shop Window in Parisian Visual Culture 1871-1882 (2016 Dublin Gastronomy Symposium); Guillaume Doizy's Le Porc dans la Caricature Politique (Sociétés & Représentations, 2009/1; n° 27); Philippe Regnier's La Caricature entre République et Censure (Presses universitaires de Lyon, 1996); Henry Vizetelly's 1882 Paris in Peril (Cambridge University Press, 2011); Morna Daniels' Caricature from the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the Paris Commune (Electronic British Library Journal, 2005) and Steve Murphy's L'arsenal de la caricature (Rimbaud et la menagerie impériale, Presses universitaires de Lyon 1991). Plus Jacques-Henry Paradis' Journal du siege de Paris (Editions Tallandier, 2008), which I bought on a whim years ago at Les Invalides.