Dan asked me to respond to Chris Mautner’s “skeptical take” on EC. I’m not sure how much I have to say specifically about Chris’s review of the first two books in our new EC series (Corpse On The Imjin And Other Stories by Kurtzman and Came The Dawn And Other Stories by Wallace Wood), but let me start with a couple of general observations about EC and its place in comics history.

Let me take a minute to set the stage. It was 1950. 1947, if you want to get technical about it, when Bill Gaines inherited Educational Comics from his father, Max Gaines — who, it’s been said, more or less invented the comic book format. Gaines neither knew nor cared about comics and took over the company unenthusiastically at the request of his mother. In 1950, he changed the company’s editorial direction, transformed it into a series of genre titles — war, science fiction, crime, horror — and recruited several new artists while retaining a few of the better ones who were already working for the company — Graham Ingels, Johnny Craig, Al Feldstein, Wally Wood. He had no grand ambitions beyond keeping the company alive. But, somehow, he got caught up in it, transformed into a discriminating enthusiast, and quickly became, for a few short years, the best comics publisher in the history of commercial comics.

Keep in mind that in 1950, the comic book was a mass entertainment targeted at adolescents, teenagers, and lowest-common-denominator adults, and stigmatized as sub-literate, which it mostly was, even before the Senate Subcommittee hearings in 1954 institutionalized the medium’s demonization.

News flash: The prospect at that time of a comic book publisher achieving high art was precisely zero. Today, there is barely a sustainable market for art- or literary-comics; in 1950, there was no market whatsoever because no one — the buying public, the publishers, the artists themselves — had even considered the idea; it was literally unthinkable. Conceptually, comic books that embodied literary values simply didn’t exist except perhaps as a private, inchoate, ontological construct on the part of a handful of practitioners. There was no artistic community to speak of; there was barely a professional community because comics was barely a profession. There was no critical establishment to argue the artistic merits of comics because adults weren’t interested enough to even read about comics (comics weren’t even movies!). There was no educated public who bought them. On the rare occasions comics were mentioned in newspapers or magazines, they were denounced as crap, which they mostly were, or vilified as socially and culturally harmful, or viewed as a bizarre and aberrant sociological phenomenon.

Neither Gaines nor Feldstein were literary mavens or theorists, they did not see comics as high art, and they were not evangelical about the artistic potential of the form. As Feldstein cheerfully admitted to John Benson, “These stories that Bill and I wrote were commercial ventures to produce a magazine that would entertain and SELL.” (Emphasis Feldstein’s.) But, they were smart, open-minded, and hip to pop culture, had a contrarian streak, and a better intuitive grasp of aesthetics than anyone else in their respective positions at other comics publishers.

They had unerringly good, if somewhat circumscribed, taste, and hired the best artists they could afford, two of whom, at least, were also restless and ambitious innovators (Kurtzman and Krigstein), and to whom they were willing to give far more creative latitude than any other publisher at the time. The artists they published were superb draftsmen, sophisticated stylists, and, in varying degrees, deeply committed to their craft and art. Gaines (and Feldstein) never aspired to create literary comics; they simply wanted to create better comics than anyone else at the time, and this drive combined with good judgment and a little luck propelled them to create some of the best commercial comics published in the first 50 or 60 years of the medium.

Gaines’s EC had an integrity lacking in every other publisher. By integrity, I mean that Gaines himself cared enough about the quality of his books to participate directly in their creative execution and took pride in the final result (most publishers couldn’t have cared less). He and editor Feldstein would spend four days out of five in story conferences hashing out the plot details for their books, based on premises and plots Gaines would bring into the office on those mornings. No other publisher was this personally involved or invested in his books.

In the impoverished cultural context of comics publishing at the time, the EC line was an astonishing achievement; Gaines’s EC came as close as a mainstream comics publisher could to being the comics equivalent of Barney Rossett’s Grove Press. What other comics publisher would even think of adapting stories from the Saturday Evening Post, use stories by Guy de Maupassant, or steal from the best — Ray Bradbury?

While I’m extolling EC’s virtues, let me enumerate a couple more before I get into the thornier questions of where EC resides in the history of comics and how to even make sense of that question.

I mentioned that Gaines and Feldstein had excellent taste when it came to choosing artists, but that’s an understatement.

First, with the exception of Orlando (who was obviously overly influenced by Wood) every one of the artists was a unique stylist, very much his own man. Gaines and Feldstein never asked their artists to imitate other artists (unlike so many publishers’ edicts to that effect) and encouraged them to establish their own distinctive visual “voice.” And within what was often a highly regimented and unified editorial vision, the artists they chose ran a spectrum — from “auteurs” like Kurtzman and Johnny Craig — who write and drew their own work and were quintessential cartoonists with a degree of abstraction and exaggeration as an integral part of their work — to the more illustrative or representational artists like Crandall, Williamson, and Evans, who, though coming from a different tradition, were still superb storytellers.

Then, you had chameleons who could be both illustrative and cartoony as the story warranted — Severin, Wood, Elder, and Davis. (Did you notice that the regulars in Kurtzman’s war books and the standard against which he measured all other artists who tried out for him, were equally good at dramatic and comedic work? I wonder if it was the absence of this humanizing quality that turned Kurtzman off to otherwise fine craftsman like Alex Toth, Gene Colan, and Russ Heath.)

Stylistically, Ingels and Kamen fit somewhere in between and were as instantly recognizable as the rest. Bringing up the rear, you had Krigstein, perhaps the most ambitious of the artists, who genuinely wanted to propel comics into literary territory (even more so than Kurtzman).

Next, portraying drama in comics form had never been one of the form’s fortes. In fact, it had almost never been done successfully. The best newspaper strips over the first half of the century — Moon Mullins, Happy Hooligan, the Katzenjammer Kids, Mutt and Jeff, Barney Google, Popeye, the Gumps, Skippy, Mickey Mouse, et al. — always couched their drama in comedic terms (usually a mélange of slapstick, vaudeville, and gags) that also, miraculously, reflected a dimension of (usually) lower or middle-class life as most urban Americans experienced it. Slapstick + kitchen-sink drama. There were only three significant exceptions that I can think of — Little Orphan Annie, Dick Tracy, and Gasoline Alley, two of which were couched in adventure terms, and all of which had humorous elements to leaven the drama or make it palatable to what the newspaper editors or artists thought was their audience.

There was certainly drama of a sort in strips like Krazy Kat and Little Nemo, but it was the graphic element of the strips that propelled them into the first rank. There was melodrama in such strips as Rex Morgan, Mary Perkins, and Mark Trail (and probably others I don’t care to think about), but these were hokey, dull, tepid soap operas. There were adventure strips — Flash Gordon, Captain Easy, Prince Valiant, Terry and the Pirates — but these, too, were not first and foremost drama (with the possible exception of Valiant) so much as melodrama within adventure, sci-fi, or fantasy trappings where the latter were just as important as the former.

But EC attempted to do straight drama in comics form, undiluted by comedy or slapstick or adventure trappings. True, most of EC’s dramatic stories were bound within genres — crime and suspense and science fiction — but they played it as straight as they could within those — and their readership’s — limitations. The preachies were the most naturalistic, many unrelentingly grim and tough-minded, such as “…So Shall Ye Reap” and “In Gratitude.”

And what other publisher would have conceived of “My World”? — a touching and uncondescending paean to childhood enthusiasms as well as an expression of love for the intimacy of the medium itself. These were the earliest glimmerings that comics were capable of expressing a level of dramatic seriousness or reflection — even though it wasn’t until the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s that such ambitions truly paid off (e.g., many of the underground cartoonists, such as Justin Green, and later, Harvey Pekar, et al.)

The stories — or the writing — weren’t as consistent as the drawing, ranging from the pure gross-out pop of the horror comics to the Bradbury adaptations or the Kurtzman war comics and Mad. Somewhere in between, in my view, were the Johnny Craig-authored (and often drawn) crime comics and Feldstein’s vast output. EC’s limitations here are all too obvious: the stories (especially Feldstein’s) were often burdened by formula and cliché, the writing prolix, overwrought, and fatuously earnest.

But the level of craft often heightens the experience; the Craig work particularly is formally inventive and often clever. But the writing, which was at least intelligently conceived, was helped immeasurably by some of the best cartoonists of their generations. It was Krigstein who said, “You simply cannot underestimate the effect of an artist on a drawn story. You simply cannot underestimate that.”

The stories occasionally rose to the level of a decent noir movie — never at the level of, say, Night and the City, but closer to a programmer or B-movie such as Somewhere in the Night; Bill Mason likened one of Wood’s short stories in Came The Dawn And Other Stories to Storm Warning, a 1951 “preachy” starring Ronald Reagan and Ginger Rogers (and an almost unrecognizable Doris Day), which I thought was on target. Many of EC’s suspense stories were roughly coterminous with an episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents or one of TV’s 1950s dramatic anthologies like Four Star Playhouse (aired the same time as EC was publishing) — not literary by any means, but not too shabby, either.

The question of how artistic values apply to comics was rarely ventilated by its practitioners in the first 50 years of the comic book and for good reason: the entire context of the comic book was devoid of self-understanding or self-reflection. The wider culture never took comics even as seriously as it took its movies, never demonstrated any appreciation for it, never rewarded achievement in any way — because the wider culture never saw an achievement there worth rewarding or cheering, and mostly for good reason.

The artists toiling in comics who cared about such matters were few and far between and usually at the level of craft, not art. The few artists who did have a sophisticated grasp of the concept, or the integrity to implement their beliefs, toiled in obscurity (such as Barks or Stanley) or were marginalized (like Kurtzman and Krigstein). There was no place for them. (The cultural context of newspaper strips was entirely different, but the cartoonists in that area still thought of themselves as something less than artists — as newspapermen, cranking out dandy entertainments to build readership — of which Caniff was probably the nonpareil practitioner and proponent. Although George Herriman thrived in this context, thanks to the patronage of Hearst, the absence of a genuine aesthetic context had its drawbacks — just as our more self-conscious age of artistes has its own set of drawbacks.)

You may have noticed that I’ve used the term “literary” pretty casually here, and I’ve noticed that it’s used at least as casually in reviews or even as short-hand, as in “lit comics,” to differentiate them from commercial or mass market comics. But can the term in fact be properly and accurately applied to comics? I often wrestle with how artistic standards ought to be applied to comics, and I’ve always concluded that the artistic values of comics are intrinsically literary. To me, there’s no getting around it; comics is no less a literary form than prose simply because images are an essential component of the former. What constitutes “literary” values won’t be disposed of in this paragraph, but maybe we can agree that form and content have to be successfully married to create something of human relevance, depth, and substance, or otherwise offer the play of pure aesthetic pleasure. Comics, after all, share many of the same or equivalent qualities that we associate with literature — narrative technique, narrative structure, fictional representation, verisimilitude, expressionism, tone, texture, authorial voice, etc. The key is to understand that the visual element is every bit as much a part of its literary expression as the words (and often more so) and that the medium has to use its own unique properties to embody what we may loosely refer to as literary values.

As an aside, it’s worth pointing out that looking for literary values in comic books from their inception in the ’30s through at least the ’70s and ’80s is a pretty fruitless task. This leads us straight into the territory of Manny Farber’s elephant art vs. termite art, but, put succinctly, there are a lot of fascinatingly recondite or rarefied or compartmentalized aesthetic virtues to be found in commercial comic books, none of which should be dismissed out of hand, but in terms of fully realized literary works — or oeuvres — very few.

I should mention here the obvious, which is that there is no consensus as to what exactly constitutes literary values. My dear friend, Don Phelps, who is on the side of termite art, has argued persuasively that strips like Little Orphan Annie, Dick Tracy, and Popeye are examples of literary visual art.

At this point, the next most salient question to pose is: Were EC Comics “good” only relative to the miserable or nonexistent standards of their competition, or were they good by any more objective standards? A mixture of both, I think, but most importantly for the purposes of this discussion, there were individual stories within the EC books that represent genuine artistic or literary achievement. Among them, for example, would be “Master Race,” “The Flying Machine,” and several of Kurtzman’s war stories — “Corpse on the Imjin,” “The Big If,” and a handful of others. In terms of the dramatic use of comics, these are as good as the medium had offered up to at least this point and probably for many years thereafter, only exceeded in artistry by a handful of poetic-graphic masterpieces, most prominently Krazy Kat and Little Nemo.

I suppose the most efficient way to point out some of EC’s merits is by taking issue with some of Chris’s judgments in his critique. He admits that “the most well-known stories still hold up” (I would say they do quite a bit more than “hold up”), and praises, slightly, the stories “Air Burst!,” (I assume this is what he meant when he referred to “Air Raid”), “Kill!,” and “Big ‘If’!,” rightly so, but then proceeds to fault several other stories written and drawn by Kurtzman, beginning with “Contact!,” dismissed as “a simplistic, jingoistic ‘us vs. them’ tale that naïvely suggests America will win the Korean War because ‘we believe in good.’”

Though it is marred by that sentiment on the last page (which Kurtzman himself lamented in the accompanying interview we published and called “dreadful”), the rest of the story is neither naïve nor jingoistic, and this criticism strikes me as emblematically glib and short sighted, almost willfully blind to its virtues. One of the characters, Durkee, is indeed jingoistic, referring to the North Koreans as ‘gooks,’ which is challenged by another soldier who fires back, “Always using that dumb word ‘gook’! You make it sound like you’re a big-shot American superman! You’re no superman! You’re just a big bag of …”

Pages three and four, in an eight-panel sequence, is a masterful depiction of violence, culminating in Durkee repeatedly stabbing an already-dead North Korean soldier in a psychotic rage (“That’s right … Durkee! Knife him, Superman! Knife him after I’ve killed him, big shot!”). This is the exact opposite of the comic-booky violence prevalent through its history; it’s viscerally repellant and retains its force today. (One can see how Kurtzman’s depiction of violence here inspired Jack Jackson’s aesthetic disposition toward his depiction of American history.) The tension here is as much between the American soldiers as it is between the U.S. and North Korean forces. After retreating in the face of heavy casualties and a superior force, the remaining troops call in artillery and air support, with one page devoted to the North Koreans being pulverized. One of Kurtzman’s goals was to show the savagery of war for what it was. (Contrary to what Chris writes, Kurtzman was not a pacifist and was not anti-war, per se.) One of the themes Kurtzman would return to over and over again was how mechanization amplified the horrors of war; he here depicts death being inflicted remotely, by tanks and aircraft.

Chris peremptorily waves off two more stories: “But even stories that appear to emphasize Kurtzman’s anti-war leanings, like ‘Rubble!’ or ‘Dying City!’ (done with Alex Toth) paint [the] Communist side in such simplistic, negative terms (leaving the Americans to always come off as [the] sympathetic guys who fight because they have to, gosh darn it, not cause they want to) that it’s hard to feel as thought there isn’t more than a little flag-waving going on in the background.”

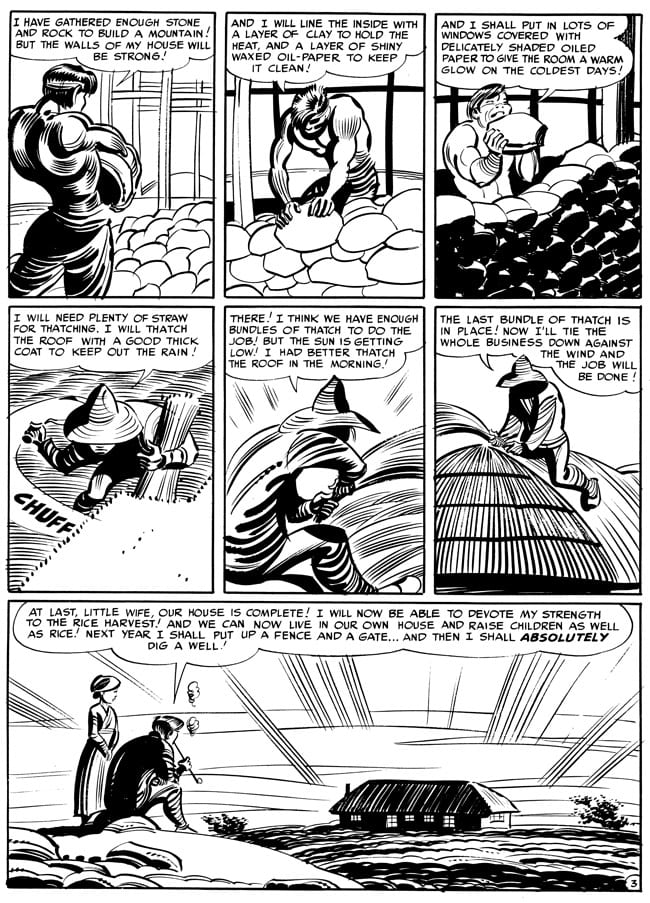

I see no flag-waving in either story. Quite the opposite: both sides are implicated in the two stories. In “Rubble!” the Chun family builds a home — meticulously shown over three pages of seven panels each — which is destroyed by “a single artillery blast” in one panel. When the U.N. (i.e., the U.S.) rolls in looking for a good position for a gun emplacement, they dispassionately bulldoze the remains of the house (and the family, earlier shown killed beneath the debris!) and put up their 155 mm cannon so that they can pummel the enemy — showing how war reduces both sides’ actions to sheer utility, and thereby diminishes their humanity. The last panel shows that the gun has been moved again, presumably to a more strategic location; the fate of the Chun family is a matter of complete indifference to both sides.

In “Dying City,” collateral damage is again the subject: A young patriotic North Korean zealot leaves his family in Suwon and eagerly goes to war — a sickeningly familiar scenario in every country that goes to war. When he returns, he finds that his father was “accidentally” killed by his own side, and he himself is subsequently blinded by a bomb dropped from an American plane. In the last panel, “American tanks roll into the blackened ruins of Suwon! Once more, the city has changed hands! The black smoke from burning oil of blasted war machines rolls over the sky, and amidst the rubble, an old man mumbles to a North Korean soldier whose body grows cold and begins to stiffen with rigor mortis!” Whose flag is being waved here?

Both stories can be faulted artistically (I could certainly do without all those exclamation points!). I see them more as being compressed than simplistic, and they could perhaps be more profitably interpreted as fables than as naturalistic war stories. But, in these two stories — “Rubble!” and “Dying City!” — Kurtzman demonstrates an admirable empathy toward both sides of the conflict, and in seven short pages tells eloquent and humane stories remarkably — though perhaps not entirely — free of ideological bias.

To bring us back to the original question of where EC resides in the history of comics: As I said, EC’s flaws are pretty obvious: Even when the artists were striving for greater seriousness than the ironic gore of the horror stories or the outrageous early sci-fi plots or even the clever but predictable crime and suspense stories, the writing was often overwrought, prolix, and ham-fisted, and the artists were straightjacketed by EC’s rigid visual grid (which Kurtzman and Craig avoided by writing their own stories, and Krigstein rebelled against time and time again).

They were Entertaining Comics first and foremost, but they also seemed compelled to break out of their commercial formulas, however finely realized, and publish stories that were fiercely honest, politically adversarial, visually masterful, and occasionally formally innovative. But, taken as a whole, the company’s output was a mixed bag. I don’t think that there’s any question that the language of the medium has grown and matured since the time of EC Comics, and that in the hands of comparable craftsman today, comics have become more eloquent and nuanced than Bill Gaines, Al Feldstein, and the artists who worked with them could imagine — or perhaps as eloquent and nuanced as they could imagine, which would’ve been no small feat in 1950.