These songs were by no means obscure at the time of “Flowering Harbour.” Both had been revived in the mid 60s. Midorikawa Ako’s 1967 version of “Casbah Woman” sold well, making the song a classic in the enka repertoire. New diva Aoe Mina’s husky performance of “Lil Back From Shanghai” provided the finale to the Nikkatsu yakuza film The Vagrant versus the Chief (Burai yori daikanbu, January 1968). There were numerous other covers of these songs by other artists besides. Most famous is Fuji Keiko’s version of “Casbah Woman,” released in early 1970, and thus recorded not long after “Flowering Harbour” was published. (It is the first song on the October 1970 live recording here).

The industry had a rubric for these revivals: “natsumero,” which is short for “natsukashii merodii,” or “nostalgic melodies.” Since soon after the war, “nostalgic melodies” programs were a force on Japanese radio. Ascendant television picked up the gauntlet in the 60s, creating a prominent forum for both new singers singing old numbers and old singers singing their own early Shōwa classics. The adjective “nostalgic” certainly reflected what many older listeners felt. Enticed by the promise of a pop market for the middle-aged, it was to them that the recording and broadcasting companies initially tailored their product. Yet one of the notable features of the 60s natsumero boom was that a fair number of its supporters (though still a minority) were in their twenties. With eighteen year-old singer Fuji Keiko’s debut in late 1969, enka fandom became (at least for a few years) even a teen phenomenon. The stereotype that enka is music for tipsy middle-aged men and aging housewives thus does not fully capture the period in question.

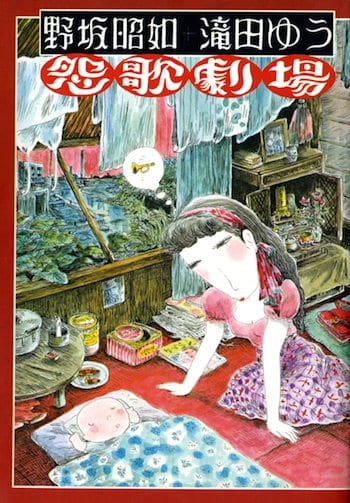

Critical reappraisal was a major factor in enka’s widening appeal. After a decade of flogging by progressive intellectuals in the 1950s, New Left literati turned the tables and touted enka as an antidote to the political sloganeering of the folk and protest songs advanced by socialist groups after the war, and to the American and British colonization of Japanese popular culture as represented by the cheery and juvenile imagery of rockabilly, surf, and the British Invasion-inspired Group Sounds. Prominent figures like poet and playwright Terayama Shūji, reporter Takenaka Rō, and novelist Itsuki Hiroyuki argued that natsumero blues reflected the real-life hardships of the average Japanese. It was, they said, focusing on the genre’s central figures of the male wanderer and the female bartender – which are, again, also the two main characters of “Flowering Harbour” – the authentic voice of individual alienation and romantic and sexual frustration. Likewise, “The Beatles’ I MY ME singing really didn’t do anything for me,” said Hayashi in an interview from 1992. “At the time, I came into things through kayōkyoku.” And in an otherwise fairly laconic interview in Garo from 1970, when asked about his favorite songs Hayashi suddenly let forth with a list of kayōkyoku that fills half a column. Garo compatriots Takita Yū and Tsuge Tadao incorporated popular music and military songs from the 40s and 50s into their stories about working class men and women, providing a glimpse of how the crusty roots of enka remained an integral part of adult identity into the late 60s. But only in Hayashi’s work – remember, the artist was only in his early twenties – does one get a feel for how Shōwa oldies were an integral part of the period’s youth culture.

Today Hayashi speaks of the “exotic appeal” (ikoku jōcho) of “Lil Back From Shanghai” and “Casbah Woman.” As mentioned before, in the new afterword for the Breakdown Press edition, Hayashi highlights as background the displacements of the high growth 50s and 60s, as has been typical in enka writing since the genre’s New Left rehabilitation in the early-mid 60s. Yet at the time of making “Flowering Harbour,” Hayashi was also surely thinking of the original context of these songs: the personal losses experienced by Japanese after defeat and the post-Imperial yearning for faraway places. That doesn’t come out overtly in the manga itself, but consider Hayashi’s own family history.

He was born in Manchuria on March 7, 1945, amidst the Japanese Empire’s crumbling. Both his father and elder sister died in China from malnutrition and extreme cold in the severe period immediately following Japan’s surrender. He and his mother finally arrived in Japan only in 1947. Life as a poor widow was extremely hard on Hayashi’s mother. Though she never worked in a bar, she became economically dependent on strange men’s affections after losing everything, including loved ones, in a foreign country during the war. Shanghai and the Casbah of colonial Algiers were in a way familiar, not as actually experienced places but as cities whose wavering colonial aura resonated with recent Japanese history. In a number of his manga from the 60s and early 70s, Hayashi used pop culture to measure family history and his personal relationship with his mother against stereotyped representations of Japanese life. Most famous is “Red Dragonfly” (“Akatonbo,” Garo, June 1968) -- which is available in English in the Gold Pollen and Other Stories from PictureBox -- which refers obliquely to repatriate experience and postwar hardship through maternal tears and children’s song.

“Flowering Harbour” is not about the early postwar period. However, it uses popular music as a vehicle to bring the sentiments of that era into the high growth 60s, using the open wounds of the post-surrender years to heighten the drama of the demographic disruptions and private soul-searchings that Hayashi speaks about in “Bohemian Living.” This is very much in the spirit of the natsumero boom. And as we will see later, graphically as well, considered within the history of comics form itself, “Flowering Harbour” is a natsumero manga. But first there is the issue of gender to deal with.

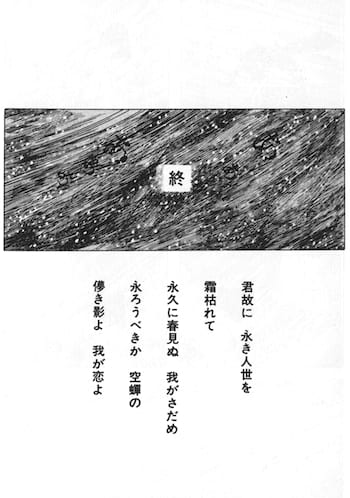

At the end of “Flowering Harbour,” Hayashi cites one more song: “Longing for Your Shadow” (“Kage o shitaite”), regarded by many as enka ground zero.

Because of you

My long life will be withered with frost

Spring shall never come, such is my fate

Was it ever meant to last?

This fading shadow

Of an empty shell

Our love

Each of the song’s verses (Hayashi has used its final verse) runs a full minute when sung. So though it takes just a few seconds to read, imagine this last page, showing just text and storm, as a slow outro with strings, sad warbling, and the cry of the winds blowing throughout.

“Longing for Your Shadow” was a bona fide oldie, written in 1929 by the legendary Koga Masao (1904-78), a kayō composer and classical guitarist whose many hits – grouped together as “Koga Melodies” – served as postwar enka’s prototypes and core repertoire. Misora Hibari’s recording of new Koga compositions in the mid 60s is typically regarded as the beginning of enka as a distinct music genre and cultural phenomenon. Inevitably, “Longing for Your Shadow” too, as Koga’s most famous song, was remade during the 60s natsumero boom.

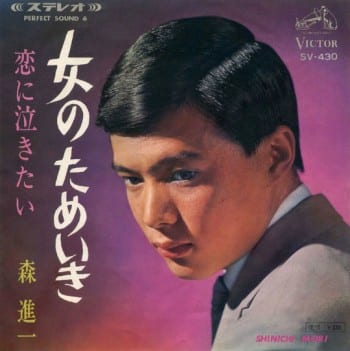

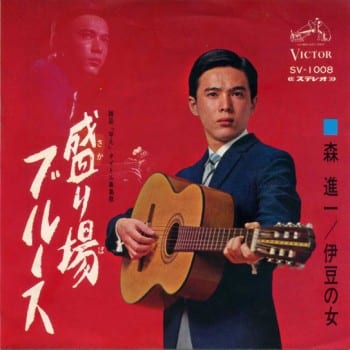

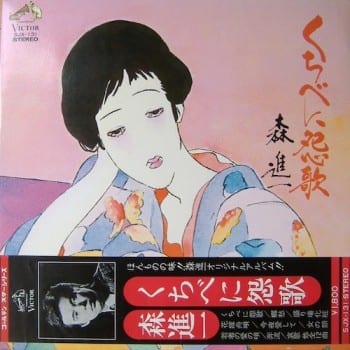

Significant for the present inquiry is that “Longing for Your Shadow” was recorded in 1968 by a young man named Mori Shin’ichi (b. 1947), who dominated the enka scene in the late 60s and continues to have a devoted following today. Since his debut, Mori has been described as singing in a “husky voice” (Japanese use the English words) or in a “heavy sighing style” (“tameiki rosen”). He was a master of enka’s requisite vibrato. In the liner notes for Mori’s Longing for Your Shadow, a LP comprising Mori’s covers of twelve classic “Koga Melodies” (a 600,000 copy best-seller upon release), Mori’s raspy vibrations are affectionately referred to as “Moribration.”

Most of the songs Mori performed featured the usual imagery of abandoned and betrayed women at small town and seaside bars. He also was beloved for ballads about mother, which complemented his handsome boyish features. But what Mori became especially known for was singing about women from (at least grammatically speaking) the women’s point of view. He was not the first to do so: there had been a small but growing number of such male singers since around 1964, though their onna-buri (woman-posturing) output was usually limited to one or two singles. What’s striking is that, in most cases including Mori’s, this cross-gendering involved almost no drag, at least visually.

As this is essential for understanding what Hayashi was doing with enka and female tears, let me go into some detail. To the extent that “Flowering Harbour” is an enka manga, it is so in the age of natsumero, as we have seen, but I think specifically in the spirit of Mori Shin’ichi.

To first get a sense of Mori Shin'ichi, watch his performance of "Harbour Town Blues" ("Minatomachi buruusu") at the 1969 Kōhaku Uta Gassen, a yearly televised all-star music special and a bastion of enka.

It’s hard to identify any overtly de-masculinizing qualities at the level of Mori’s voice. “His voice gives sound to the melodrama of enka,” writes Christine Yano, with no reference to the gendering of his lyrics, “rough rather than smooth, striving rather than static, kurai (dark) rather than akarui (light), filled with emotional tension rather than relaxed.” In an interview in Garo from 1992, Hayashi describes Mori’s voice as “androgynous, pretty close to Adamo,” referring to the Belgian-Italian singer. But I suspect this is a side effect of the lyrics and Mori’s boyish face and physique. He was only nineteen at his professional debut in 1966. Mori’s voice is a bit higher than some other male enka singers, which creates a striking effecting as he frequently dips into a wavering moan, like honey over gravel. But, whatever its natural pitch, Mori’s voice in practice rarely got as high as Adamo’s. It was forced, on the contrary, intentionally low.

Interestingly, the terms “husky” and “sighing” were also used for Mori’s contemporary Aoe Mina, a moderately deep-voiced woman. The two were even coupled on a handful of records. When one speaks of Mori’s onna-buri, they are usually talking about the subject position assumed through the lyrics. But considering the resemblance to Aoe’s smoky, sexualized, and unambiguously feminine jazz singing, Mori’s throaty style might itself be called “woman-posturing.” Indeed, his debut single “A Woman’s Sigh” (“Onna no tameiki,” 1966) identifies melancholic exhalation as a specifically female vocal sign, but the gesture is subtle by kayō standards. Female singers like Hibari and Suizenji Kiyoko had been performing male numbers for some years (Hibari since the 50s), oftentimes in male costume and in a lower voice. Suizenji wore her hair cropped boyishly short. Mori, on the other hand, like other male singers at the time, usually wore a sweater or suit and tie, and never strayed from his gender’s sartorial norms. Some of his early record covers, however, like that of “Flowers and Tears” (“Hana to Namida,” October 1969) showing the singer coyly staring at the photographer with a rose in one hand, would have easily lent themselves to being read as gay.

In the same Garo interview as cited above, Hayashi was asked why he thought there occurred this sudden gender flipping in Japanese popular music in the late 60s. “Various things come to mind, but it’s often said that the period when Mori debuted resembled the situation in the Taishō period. For example, when Kōzō Okamoto was arrested after the Lod Airport Massacre in Tel Aviv, during the police questioning he named Taishō period terrorists. Even in my own Scarlet Crime Flowers [a collection of drawings and calligraphy published in 1970], I illustrated things from Shōwa kayō back to Taishō children’s poems. There’s something special about the Taishō period, when men and women crossed. I don’t know if you call it unisex, but this feeling that something’s neither male nor female. That happened again after the war. There was certainly something like a women’s wave, a revolution of women’s consciousness. If postwar American democratization resembled the movement from Edo to Meiji, then Taishō naturally comes next.”

Critics of the period, however, were not so interested in the longer historical process. What was important to them was the what of Mori’s art not the why. Such was also the case, I suspect, with Hayashi at the time of “Flowering Harbour.” It boiled down to Mori’s body and voice, and the erotic friction between what he sang, how he sang it, and how he looked. Inomata Kōshō, who wrote many of Mori’s early hits, recalled his first impressions of the singer as follows: “Physically he was fairly small, with a pale child’s face. There were still traces, not of a young man [seinen], but of a boy [shōnen]. His face was small, making for a nice overall balance. His lips were thick and pouty. There was an odd sexy mood to him, the kind that you think a middle-aged woman might like.” Part of the initial publicity campaign for the new singer, writes Inomata, involved personally seducing women with Mori’s voice by going incognito to clubs and bars and asking upper-aged hostesses to call in to cable radio stations and request those new husky sighing boy songs. Similarly, in a piece for the magazine Music Echo in 1969, Koizumi Fumio, doyen of kayōkyoku studies, listed amongst the reasons for the popularity of this petite “handsome boy” the image he projected of “easily being hurt.” It was the very inverse of what “male-posturing” female performers like Suizenji and Hibari did, which was hyper-masculinity through images of invulnerability and broad-chested brawn.

Other critics took a more abstract approach. Since the 80s the question of cultural authenticity (Japanese-ness) has been at the center of enka studies. But back in the 60s the core issue was instead social and emotional authenticity. Did a song or singer capture the experiences of the common man or woman in postwar Japan? When it came to enka, most answered an emphatic yes. But despite audiences sharing in singers’ sighs and tears, producers of the genre had been very conscious about the “put-on” quality of enka since the genre’s rise in the early 60s, something that is particularly obvious in gender-crossed songs. This was not lost on observers. In the same article mentioned above, Koizumi Fumio wrote in reference to Mori, “While women have all sorts of feelings, what they are particularly filled with is not quiet and gentle love, but emotions that are much more violent and real. It would be most natural and obvious for a woman singer to sing about women’s feelings. But to express feelings that are not obvious, it seems that it takes a male singer.”

Women suffer. But how should they manage and express that suffering? What Koizumi appears to be claiming is that Mori’s male body served as a wedge to crack open stereotypes of female loyalty and submission in popular music. He was thus able to give voice to emotions that, even if we judge them as no less disempowered, were at least more honest to commonly held feelings of romantic distress and resentment. Given Hibari and Aoe, it is doubtful that a man alone was responsible for this shift. (A period performance of Hibari's "Sad Sake" (1966), also written by Koga Masao, can be found here.) The point is that, for male intellectuals at least, and given Mori’s brisk sales presumably also for a large number of grown women, this despairing female type was thought to have crystallized in a, gender-wise, “non-natural” abstraction. Mori was, in emphasizing artifice, paradoxically able to produce an effect of greater authenticity, so the thinking seems to go. Hayashi’s work I think succeeds in a similar way.

A slightly different take on Mori comes from Garo columnist Ueno Kōshi. “There can be no kayōkyoku divorced from its singer,” he states in an afterword to a 1970 collection of student protest songs and parody placards. “Only in the flesh of the singer does a song take actual shape.” A common idea, but in a discourse dominated by sociologists interpreting popular music largely on the basis of the lyrics alone, Ueno’s argument for embodiment remains fresh. It was a special quality, he argued, not of all music (modern jazz and the Beatles failed on this count), but particularly of 60s kayōkyoku. “To us, real kayōkyoku is not the kind you listen to and sing. It is, as a phenomenon ceaselessly being born and disappearing, a flow that passes through our bodies.” As his first example Ueno takes Mori, who he had just been watching on the tube. Mori’s singing was something not just to be heard. It was something you also had to carefully watch. “A performance by I Musici, I don’t need to see. I can close my eyes and just orient my ears toward the sound. But that won’t work for kayōkyoku. Rather than listening you have to watch, especially in the case of singers like Mori Shin’ichi whose face is involved each and every moment in the act of singing.”

This is not a sexualized reading per se. But it shows how enka’s felt authenticity was ultimately tied to, not just adequately dejected lyrics, but a kind of erotic seduction based on the singers’ body and voice. This was all the more acute in Mori’s case because of the obvious contrast between what he sang about and what he sounded and looked like. Ueno writes of other enka singers that tickle his innards. But it is specifically Mori for which he insists on the visual dimension – implying that the seduction was premised specifically on watching how that voice was able to hold together a face of one sort with the lyrics of another. Ueno doesn’t mention gender, but here I think two things are essential. One, Mori didn’t do drag. That would have carried his body too far away from norms of masculine heterosexuality. Two, despite his boyish features, he wasn’t a falsetto. The feminine in Mori’s singing dove the other direction, downward. This creates for an interesting gender dynamic. For me, the fascination of watching Mori sing – there are old 60s clips available online – is seeing an androgynous young man, who one suspects to sound like a boy, striving to sound like a deep voiced woman. His body says male. His lyrics say female. But his voice says what? It might seem odd to describe a male singer as doing otoko-buri – “male-posturing” – but it seems plausible given Mori’s apparent attempt to simulate low voiced female jazz singing as a complement to despairing female lyrics.

Looking back at the era from the 80s, Ueno built on his younger self’s thoughts to theorize about Mori’s “woman-posturing.” For him, that occurred mainly in the lyrics. While such gender-crossing had already become fairly common in kayōkyoku, explains Ueno, Mori’s “anti-naturalism” took the artifice to a “meta-level.” The almost forced passion with which Mori sang about women of the night drew attention to the fact that a physical body was trying to inhabit a subject position that was neither its own nor believably real. “Of course, the woman-posturing of Mori Shin’ichi in his heyday between 1966 and 1969 had nothing to do with actual women. It was always a perversion. Any sane woman would probably find the imagery to be the arbitrary and self-serving fabrication of men. Nonetheless, what’s amazing about Mori Shin’ichi is that with him the perversion was total. He tried to give the perversion itself a physical body.”

What’s missing here, in addition to a discussion of the dynamics of Mori’s voice, is what songwriter Inomata importantly pointed out, which is that Mori was aggressively marketed at adult women, the “arbitrary and self-serving fabrication” of male producers notwithstanding. If adult women were indeed Mori’s primary audience, the relationship between fan desire and the singer’s “perversion” might run as follows: he was boy enough to say mother, man enough to seem lover, but neither too boyish nor too masculine to conflict with the narcissistic pleasures his lyrics and sighs provided.

Not all of this is directly relevant to a discussion of manga. But at least I hope it gives you a sense of how complicated were the gender dynamics of 60s enka. In attempting to adapt enka, Hayashi was joining a queer enterprise.

(cont'd)