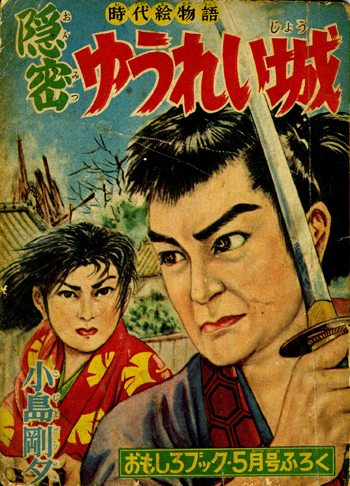

Staying with the jidaigeki genre, but jumping ahead a few years, let’s turn to Kojima Gōseki (1928-2000). You know him as the artist for famous '70s gekiga like Lone Wolf and Cub and Samurai Executioner. Before teaming up with Koike Kazuo, Kojima was best known for writing and drawing historical romances, mainly for girls, which he had been doing since around 1957. He was not known for his story-telling. He himself was proud only of his draftsmanship. He was lauded both for his naturalistic figures and attention to details of historical dress and coiffures. It was on that reputation that Shirato Sanpei hired Kojima to do the drawings for the first years of The Legend of Kamuy in Garo. In the mid-late '50s, Kojima created at least a couple of emanga, serialized as furoku inserts for major youth monthlies. The one sample I have on hand is titled Assassin of the Ghost Fortress (Onmitsu yūrei jō), from the May 1957 issue of Shūeisha’s Omoshiro Book. The magazine was founded in 1949 to capitalize on Yamakawa Sōji’s popularity.

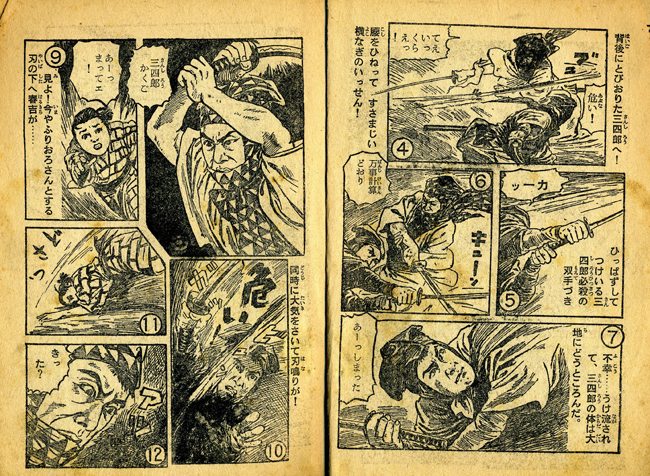

The story of Kojima’s emanga, or at least what I have gathered from the single chapter I’ve read, is utterly conventional. There is a boy named Manjirō. He has discovered that he is the son of the shogun Yoshimune. The proof of his birth is an inrō (a lacquer ware tobacco case) designed with a flying dragon. On his way to Edo to claim his heritage, the inrō is stolen, first by a female assassin named Osen and then various other hooded swordsmen and ninja vying for the treasured heirloom. Manjirō has to fight them, as they fight each other, with swords and throwing blades. There are moralizing dialogues about loyalty, friendship, and commitment, straight out of an earlier era’s bildungsroman. The drawing is not inept, but at times gets very awkward, especially with foreshortening. It certainly pales in comparison to the Club-period pen illustrations from which it is derived. Corners are clearly being cut to adapt “illustration” to the multiple panels and publication pace of manga.

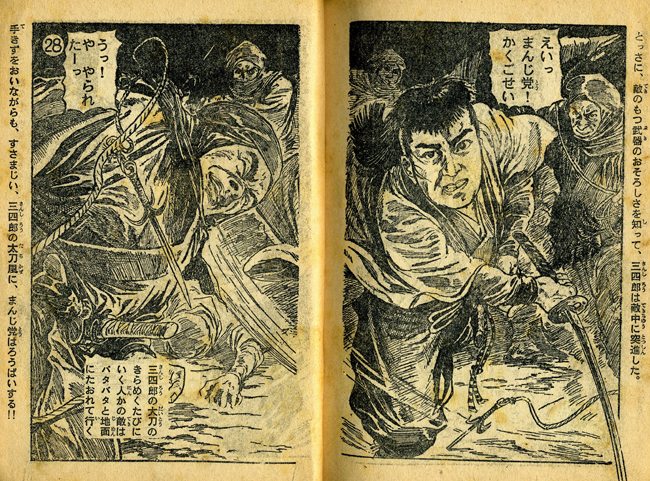

Kojima worked as a kamishibai artist from the late '40s to the mid '50s. One might argue the influence of that medium in an emanga like Ghost Fortress. The influence of manga, however, is much stronger, stronger than in Oka’s White Tiger Mask, concluded three years prior. There are now, for example, a large number of inscribed sound effects. Some of these are rendered poorly, with the interior guidelines accidentally drawn in, as if Kojima inked his pencil lines too quickly or worked directly in ink. There are a number of panels depicting focused details of trees and weapons, as well as a few with nothing but the sound and visual reverberations of physical impact. One rarely sees this in older emonogatari. I don’t believe it appears in Oka’s White Tiger Mask. The humor in Kojima’s emanga also seems derived from manga. In one panel, a swordsman and a boy find themselves suddenly face to face. The swordsman recognizes him, stating, “You are the boy from the last chapter” – the sort of easy reflexive joke Tezuka liked. There is a group of dopey buffoons, figures of comic relief typical in period movies but not (from what I’ve seen) in emonogatari. One runs about with a wood tub stuck over his head. His mates tease him by thumping – “pon pon” – on the top. Later, one of their gang follows the sightline of a swordsman – literally a dotted line stretching like a string in space – to end suddenly in the face of Manjirō’s pet monkey and a question mark. Emonogatari at this late stage seems to be losing its puffed-breasted seriousness, opening up to the laughter and self-referential gags of manga and the movies.

(Continued)