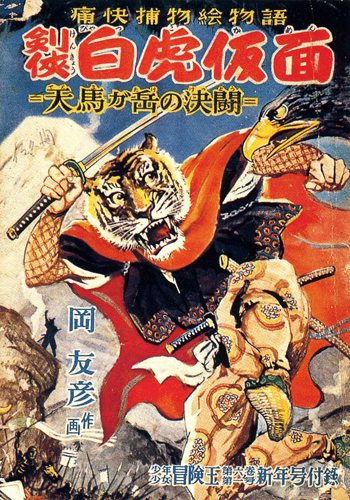

Let me begin with what is widely regarded as one of the earliest and most accomplished works in the medium. Oka Tomohiko’s (1917-90) White Tiger Mask (Byakkō Kamen) was serialized in the monthly Adventure King (Bōken ō) between June 1951 and February 1954, and on occasion as a 48-page furoku booklet inserted into the magazine’s pages. The black and white images shown here are from the 1975 collected edition.

The setting is Edo (Tokyo) during the youth of the shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune (1684-1751). The titular hero is so named because he wears a white tiger’s head. It wears it like part of his own body. He is able to open and close the mouth at will, holding his sword in his mouth as he scales a ship, roaring open as he attacks. White Tiger Mask is described as a “swordsman of justice” (“seigi no kenshi”), but one of a rather conservative sort. In truth, his name his Tsukinosuke, a spy for the shogunate. Accordingly, White Tiger Mask’s brandishes his sword and revolver to stop various plots to undermine the Tokugawa. The first episode, for example, involves a band of thieves possessing a map that shows secret underground passages into Edo castle. They intend to traverse them to set explosives. They are not stopped easily – White Tiger Mask barely survives a number of fights – but eventually through swordsmanship, cunning, and perseverance, he is able to turn them over to the police.

In the postscript to the 1975 edition, Oka recalled being attacked at the time by The Children’s Defense League and other groups for promoting “militaristic” and “anti-democratic” values. He himself thought he was writing a story against “anarchic forces that disregard authority, disrupt society, and destroy the peace of the people.” He also thought his work was mainly about “human energy” and personal striving above and beyond “morals and ideology.” Critiques of “militaristic” and “anti-democratic” are certainly exaggerations, but they are not entirely off the mark. White Tiger might not be fighting for the Emperor. However, he does work for an authoritarian government. His enemies are definitely criminal – thieves, bandits, pirates – but it is in the name of law and order, and not the common man, that he fights them. His main ally is the Swallow Kid, a young pickpocket who, again, helps the Edo police. There is a clear ideology in White Tiger Mask, Oka’s disclaimer notwithstanding. Good and evil are measured throughout by absolute degrees of respect and disdain for law and the powers-that-be. There is no good against authority. There is no bad inside it. It’s a police view of the world.

It’s no surprise White Tiger Mask evoked the pre-1945 past for postwar readers. Its moral values and storytelling aside, the drawing in emanga is rarely so purely of the flesh and blood of early Shōwa youth fiction as it is here. One can see clearly here how magazine illustration of the 1920s and 30s was probably at least as strong an influence on postwar emonogatari than was kamishibai imagery. Oka himself debuted as artist in 1934 in Shōnen Club. His first works were manga, but by 1940 he was doing illustrations. Stylistically, Oka took after Itō Hikozō (1904-2004), one of top figures in the field since the 1920s, and also associated with militaristic fiction during the war. The image shown here originally accompanied Osaragi Jirō’s The Kakubē Lion for Shōnen Club, specifically the May 1927 chapter. This was the first youth-oriented version of Osaragi’s famous Kurama Tengu series, set in the late Edo period (mid nineteenth century), about a hooded “swordsman of justice,” often appearing on horseback, now pursued by the shogunate’s special police force, then helping them to crush saboteur gangs, only always on his own side and those of his immediate friends, against both authority and terror. Oka’s White Tiger Mask is clearly inspired by Osaragi’s Kurama Tengu. He has become only more conservative. Oka’s drawing holds its own against Itō’s exquisite line-work, but is certainly quicker, looser, and rougher, inevitably so because of differing medium: more fracturing into small panels, more pen work per page, more pages. Like I said, it is little surprise Oka evoked specters of militarism. Whatever the subject matter, to draw like this in the early 1950s, not ten years after the war, was bound to evoke the world of pre-1945 values and fantasies. However, Oka and his publisher were probably concerned more with money in the present: one of Whiter Tiger Mask’s title pages is decorated with a strip of celluloid, suggesting ties to the post-Occupation boom in chanbara “sword fight” films.

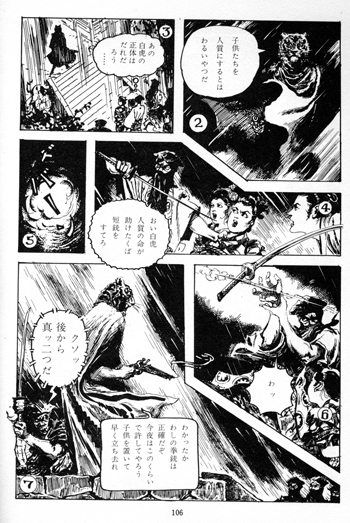

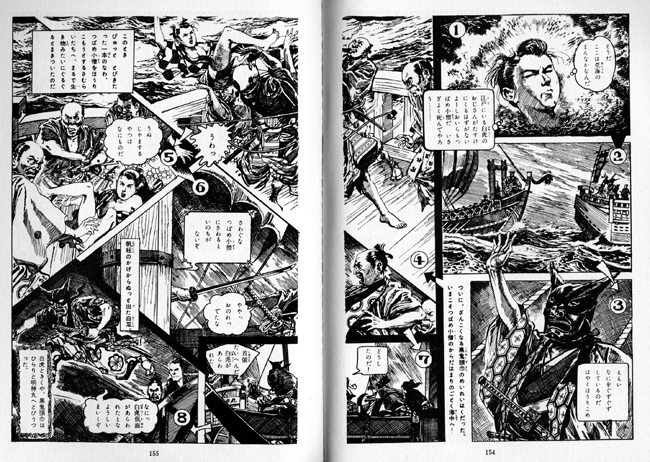

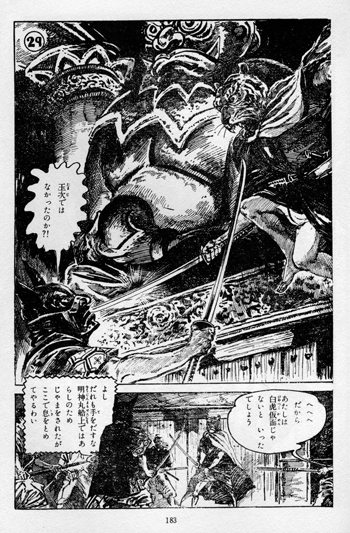

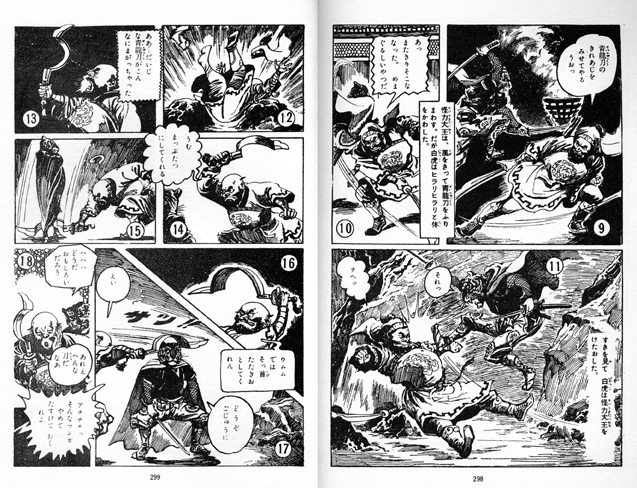

Graphically speaking, the main difference between White Tiger Mask and illustrated fiction and emonogatari of yore is the use of dynamic panel layouts and speech balloons. Not having the surveyed the material thoroughly, I cannot say for sure, but it is my general understanding that even round panels are rare in traditional emonogatari. They certainly appear in Nagamatsu’s seminal Golden Bat for Bōkatsu (mentioned and illustrated earlier), but there in the context of a layout that I assume is derived not from emonogatari but instead comics. One sees increasing numbers of shaped and round panels in more traditionally formatted illustrated prose fiction in the 1950s, but they seem to post-date their use in emanga like Golden Bat and White Tiger Mask. The former is quite smooth and slowly paced. The curved frames allow the eye to glide across the page, creating resonances between panels that are not necessarily adjacent. In contrast, the layouts of White Tiger Mask are super busy, claustrophobic, exhausting to follow, kept legible at times only by small tags indicating panel order. Oka’s work is also extremely wordy: the pictures seem largely there to embellish the story rather than tell it. The use of speech balloons seems largely dictated by conventional emonogatari: the characters feel like they are speaking dramatic “quotes.” The feeling is one of traditional prose crammed into the language of comics. The goal I imagine was to visually activate the prose. The result is well-crafted din.

Towards the end of the series (circa 1954), there begin to appear some elements that suggest that Oka was further loosening his ties with the past and opening up to comics even more. The influence comes packaged typically in humor. A few balloon-like question marks appear, one wrapped quizzically around a female character’s floating head, another popping up above the Swallow Kid’s head as he screws up his face in puzzled thought. A few moments of slapstick are interjected into action scenes, most abruptly during an exchange with the Qing-clad Strongman King. White Tiger Mask kicks him in the face, he falls over and onto his sword, bending it upon a rock. His surprised discovery of his weapon’s contortion is traced with a dotted line. He slices at White Tiger, who pulls in his arms and allows the sword’s curve to wrap around him, before dodging a blow to the face in a similar manner. The Chinaman’s frustration is expressed through dopey looks and balloon-like question marks. At the very end of the page, the Swallow Kid cries out from off-page, “Cut out that kind of manga and save me!” He is presently burning at the stake, yet Oka finds time for jokes. If White Tiger Mask began as an attempt to do dead-serious Club-type fiction in emonogatari, by the end it was clearly devolving into the age of comics.

(Continued)