Emily Carroll drew her very first comic in May 2010. Thirteen months later, she won the Joe Shuster Award for Outstanding Web Comics Creator. So go ahead, pull "meteoric rise" out of the cliché file and wave it like you just don't care—Carroll and her comics have earned the term. Like many readers I became aware of her when her lushly colored gutpunch of a horror webcomic "His Face All Red" made the rounds last Halloween; since then she's made the process of tracking her work down across various dedicated URLs and LiveJournal posts much easier by collecting all her finished comics on her website, EmCarroll.com. There you can also find an extensive sample of her illustration work, which consists as much of done-for-fun fan art for Dune, Red Dead Redemption, and the like as it does hired gigs. That illustration work is so strong—graceful curves and inviting angles arranged with geometric precision for maximally sensuous appeal; this is a person born to draw a woman's lower leg ending in pointed toes—that you could be forgiven for thinking her comics would be eye candy and not much else. But what impresses me most about Carroll is that her sequential art is as ambitious in form and uncompromising in tone as her standalone pieces are lovely to look at, all while sharing in that same loveliness.

My interview with Carroll was much delayed since we first made contact—my wife and I had a premature baby; Carroll traveled, went to conventions, got engaged to her girlfriend (artist Kate Craig) … and made a multi-part minicomic series, That Night in June, telling a single story across seven separate interwoven individual issues sold as a set. Carroll's young career is that sort of thing—take a couple of months to interview her, and she's apt to have forged a whole new chapter for herself. Here's her story as it stands right now.

Sean T. Collins: I want to talk to you about "His Face All Red", first and foremost. Simply put, I don't know if I've ever discovered a cartoonist's work as suddenly as I did yours, thanks to that strip. One day I'd never heard of you; the next day, it was Halloween, and you and that comic were everywhere, frequently accompanied by endorsements the gist of which were, "Seriously, I know you're all horror-comic'ed out, but you must read this." What was the origin of that story?

Emily Carroll: The credit for that story's inspiration probably goes to the late night radio show Coast to Coast AM (a conspiracy/paranormal/UFO related program based out of L.A.), where a number of years ago a man called in to relate the story of this supposed "bottomless hole" he'd discovered on his property. While the caller went on to phone in a number of times more over the course of a couple years—building on this story in some pretty far out (and yet always entertaining!) ways—it was the original idea of a bottomless pit that really got me thinking about the story that eventually became that comic.

At the same time, I'd written a fairy tale sort of story that dealt with two brothers hunting a beast in the woods, which resulted in one brother murdering the other for his own gain. And that, in turn, had been inspired by folktales where a character's act of betrayal catches up to him in the end (typically in some gruesome way). But since I was never especially happy with the ending I'd originally written for that story, I brought in the idea of the bottomless hole to see how it would work with what I'd already created. And actually, originally, the entire comic was going to take place during the brother's descent into this mysterious pit, with him telling the story of what he'd done as he went.

As for why I made it in the first place, it was just an experiment more than anything else—I wanted to try writing and drawing a scary story, and thought, given the proximity of Halloween, it was a good time to give it a shot.

Collins: I'm loath to go into enough detail to spoil the ending, but for me, that's what got the whole comic over. More than that, it's what's kept me returning to it; it's one of the few comics I've ever read that genuinely has the power to creep me out when I think of it as I stumble to the bathroom in the dark in the middle of the night, you know? I'm curious as to how early on in the process you had in mind that final image, and perhaps more importantly, the pacing and formatting with which you approached that final image.

Carroll: First off, it's really neat to hear that it had that nighttime-stumble-to-the-bathroom effect! When I was writing it I was wondering if it would be able to carry that sort of creepiness factor, given that technically the only person who should really be scared of what lurks in the dark is the protagonist of the story. So thank you, that's really cool.

That image was actually one of the first decisions I made when I started seriously working the story out. I had the beginning of the story in mind right from the get go (that sequence of panels in the tavern), and then the ending came to me, and from there I worked out the route from A to B, if that makes any sense. Originally the narration was going to carry through until the very end, with the protagonist describing a sound he heard accompanying that final image (which, of course, readers would never be able to hear due to it being a comic), but I thought that including too much text felt clunky and took away from the tension. The silence went better with blackness too, which is when I broke up the final images so that they would each have their own page to (hopefully) maintain that tension.

That was also when I decided on the title too, which led to me introducing it into the script a bit earlier on in the story.

Collins: In a way, it felt like a response to or revision of your Brothers Grimm adaptation, "The Hare's Bride"; the two strips share that sense of mounting unease giving way to terror, but "His Face" doesn't give you an out in the end. The story has a sort of fairy-tale/scary-story feel to it. Were you responding to those sorts of things?

Caroll: Definitely, sure! I think a lot of fairy tales have that sort of unease built into them, just because they introduce so many elements that they never explain, and use fairy tale logic—the kind that isn't really logic at all, but has that matter-of-fact feel to it anyway—and the reader just has to roll with it. It's very dream-like, and I'm definitely into exploring that kind of storytelling right now.

And in the original story of "The Hare's Bride", the girl does escape at the end. In most fairy tales where someone has caused some wrongdoing though, they pay for it by the story's end, which is (arguably, I suppose) what happens in "His Face".

Collins: It's not that I've never seen "overnight success" webcomics before—the Nicolle Brothers' Axe Cop exploded within days of its creation, for example, and 2001 by this column's last subject Blaise Larmee seemed to stun a lot of people really quickly as well—but "His Face All Red" appeared to have this weird cross-quadrant appeal: Wonks and webcomics aficionados could appreciate the McCloudian "infinite canvas" aspects of the formatting and layout, horror people could appreciate the darkness of tone and effectiveness of the ending, people who simply enjoy art with self-evident chops could soak it in like they might do with your illustration work, and so on. What was it like, suddenly becoming the subject of that kind of acclaim from that wide a sampling of the comics internet?

Carroll: Ha ha, pretty overwhelming actually! I absolutely never expected it to gain that type of attention. And I think a lot of it's popularity had to do with putting it up on Halloween, which I originally did just to give myself a deadline to have it finished by. But yeah, even though the response was really positive, it did make me a little jittery, and I had to take a bit of a breather from the internet for a few days.

I'm immensely grateful for it too, though, because it's that sort of encouragement that led to me thinking that maybe there would be an audience out there for my stories beyond just my friend base, and I honestly never thought I'd be capable of getting my work out like that before.

Collins: Along those lines, I tend to be skeptical about claims that comics that appear on the web "ought" to be laid out in such a way that they could only appear on the web. To me, it seems that if you want to take advantage of the flexibility of the web, by all means, but if you simply prefer to use it as a place to publish comics that could just as easily be printed out and stapled together, I'm no more going to hold it against you than I would take a print comic to task for its failure to be a pop-up book or the size of one of those giant Little Nemo collections. You've published some comics on the web that take advantage of the long scroll, the ability to have "pages" of varying sizes, and so on; you've also published some that don't. Do you have a preference? If so, does it stem from a principled stance on the issue, or do you just do what works for any given project?

Carroll: It stems more from just what I think will be most fun, really. And since—when I started doing comics—I'd never done comics for print, I wasn't in the mindset of doing pages anyway, which maybe led to me not really adhering to that standard when I started in on my own attempts. I like the idea of scrolling just because it's fun to play around with revealing images that way, but you can play around with the same thing using page turns too really.

And actually, now that I am working more on print comics, I find that it's tough for me to figure out how to pace things and place things on the page (though when I say "tough," I mean it's still a good time, just a different sort of challenge). So I like doing both, and I like reading both, in print and online. For me, it depends on how I want to tell the story.

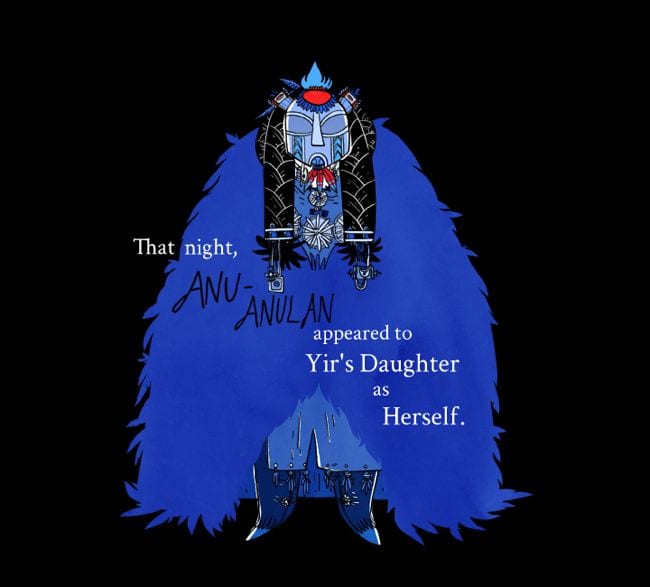

Collins: "Anu-Anulan and Yir's Daughter" is an example of the former type of comics, with its big rhapsodic climax. It was interesting to me to see you use the "infinite canvas" to convey a positive emotion like love while much of your other work has used it to evoke fear. How similar was the thought process behind the two kinds of comics?

Carroll: I guess it's similar in that I wanted to pace reveals in a certain way, whether they be of one emotion or another. I'm not sure, I wasn't really thinking of the format itself when I was creating the end of "Anu-Anulan", more just the information I wanted to convey. I wanted to show that they ended up in love, but that love needed to include moments that were both mundane as well as passionate—and simply showing a panel of them old together at the end wasn't enough. And I also wanted to show that it's not just a single sweeping romantic gesture that makes a love story, it's also the everyday moments (like having a meal, or taking a walk, or just having a laugh together) that can mean just as much.

I did think of the ending fairly early on though, so I suppose it's similar to the other comics in that regard too.

(continued)