THE LONG-AWAITED, HIGHLY TOUTED, deeply resented DC attempt, once again, to capitalize upon Alan Moore’s watershed creation, Watchmen, arrived about two years ago in the form of the first issue of a 12-issue mini-series, Doomsday Clock. In this series, ostensibly a sequel, writer Geoff Johns attempts to meld the DC universe of superheroes (Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman et al) with Moore’s Watchmen universe—Ozymandias, Nite Owl, the Comedian, Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan et al, blissfully ignoring the fact that Moore’s heroes (or anti-heroes) were never a group called “The Watchmen.” Watchmen was the name of the comic book, not of a group of heroes. And besides, most of Moore’s heroes are now presumed dead. So how— ?

Just one of the many bafflements that cling to Johns’ work.

Now, at last, issue No.12, the end of the series, has arrived. We may expect the arrival of the Doomsday Clock graphic novel compilation momentarily. But before that arrives, we’ll review No.12 before we end this disquisition. And we’ll say a few words about whether the series achieves its presumed purpose.

But by way of preparing for that seance, let me summarize the reviews I have committed on the predecessors, Nos.1 through 11. As monumental an undertaking as this series deserves a nearly thorough examination, but what follows herewith is less a cumulative review than a sort of reader’s log, an issue-by-issue report on what happened and how the “story” is unfolding.

The events of the first issue fall handily into three parts. In the first hysterical, panicky part, we see the New York City massacre depicted in Moore's work in progress, a confused melee of violence and disorder that a narrator sees as apocalyptic, heralding the end of the world. The narrator, we eventually discern, is Rorschach, who, known for his gloomy outlook, is scarcely a reliable witness, but even if the end of the world is not at hand, the pictures convince us that some sort of riotous destruction is going on.

The events of the first issue fall handily into three parts. In the first hysterical, panicky part, we see the New York City massacre depicted in Moore's work in progress, a confused melee of violence and disorder that a narrator sees as apocalyptic, heralding the end of the world. The narrator, we eventually discern, is Rorschach, who, known for his gloomy outlook, is scarcely a reliable witness, but even if the end of the world is not at hand, the pictures convince us that some sort of riotous destruction is going on.

In the second and longest part, Rorschach is the principal actor. But it isn’t, actually, Rorschach: the Rorschach of Watchmen is presumed dead (disintegrated by Dr. Manhattan); the guy we see here in Rorschach’s mask, fedora and trenchcoat is an imposter, but he talks and acts like the genuine article. He’s broken into prison with the object of freeing a woman, Erika Manson, so she can help him save the world. But she won’t play along unless Rorschach frees her husband, too, and promises to find their son. He does.

The three of them (Erika’s husband, a mute with a strong face that reminds me of Clark Kent) leave the prison and drive to a dimly-lit underground sort of place where they see Nite Owl’s vehicle, the Owlship, and meet Ozymandias, Adrian Veidt, in full regalia, who tells Erika that he needs her to help him find Dr. Manhattan, who is powerful enough to save the world—or, as Rorschach puts it, to “find God.”

Next, for the third part of the book, we are transported to Clark Kent’s bedroom, where he’s asleep with his wife, Lois Lane. He has a nightmare that reenacts the death in a car crash of his parents, the bucolic Kansas Kents.

Clark awakens with a jerk, tells Lois what he’s been dreaming, and she says she can’t remember when he last had a nightmare. To which Clark responds: “I don’t think I’ve ever had one.”

End of No.1.

The project to find Dr. Manhattan is cliffhanger enough to bring me back. The connection to Superman isn’t at all apparent, but I had hopes that it would emerge.

At first reading, I was put off by the purple prose of the first few pages, describing the rioting in New York City: “We slit open the world’s belly. Secrets came spilling out. An intestine full of truth and shit strangled us.”

But once I figured out Rorschach was talking, I got over it. And the rest of the book is engaging and not far off the mark Moore set.

The issue’s completed episode (essential to any good first issue: a completed episode reveals aspects of the personalities of characters as well as the ability of the story’s writer to do his job) is the long, central section with Rorschach guiding the narrative. His characterization is a solid reminder of Moore’s creation, and the episode finishes handily, having achieved its objective, bringing Erika to Ozymandias. Rorschach is, in fact, the best thing in this issue. And his cryptic utterances and sulky behavior summon up remembrances of Moore’s memorable character.

And there are enough oblique allusions and inexplicable references to echo the general ambiance of the original. Plus a few references purely contemporary.

A newscaster keeps us up-to-date on the unfolding disaster as it transpires in New York City:

North Korea now capable of reaching as far inland as Texas. ... Hundreds have broken through the wall and flooded into Mexico. Thousands more are expected to follow.

So the Trumpet’s wall fails in reverse.

The news continues:

We are still waiting on a statement from the President. ... The President scored a hole in one early today, beating his previous record. ...

The search for Adrian Veidt continues, the newscaster tells us, adding that his arrest and conviction will absolve the U.S. of accusations of “collusion in the New York City massacre.”

Stay ’tooned.

THE SECOND ISSUE is pretty straightforward compared to the first issue. Marionette and Mime (Erika and her husband) don costumes and go out to rob a bank. Dr. Manhattan shows up briefly and eyes Marionette’s cleavage. Then Adrian Veidt (aka Ozymandias) is in the Nite Owl’s flying vehicle, the Owlship, with Marionette and Mime and Rorschach; they take off for a parallel world. Veidt has taken Marionette and Mime captives: he wants Marionette along because she was something in Dr. Manhattan’s past that might be used to advantage. Rorschach and Veidt intend to interview the “smartest person” in that world to find out where Dr. Manhattan is.

THE SECOND ISSUE is pretty straightforward compared to the first issue. Marionette and Mime (Erika and her husband) don costumes and go out to rob a bank. Dr. Manhattan shows up briefly and eyes Marionette’s cleavage. Then Adrian Veidt (aka Ozymandias) is in the Nite Owl’s flying vehicle, the Owlship, with Marionette and Mime and Rorschach; they take off for a parallel world. Veidt has taken Marionette and Mime captives: he wants Marionette along because she was something in Dr. Manhattan’s past that might be used to advantage. Rorschach and Veidt intend to interview the “smartest person” in that world to find out where Dr. Manhattan is.

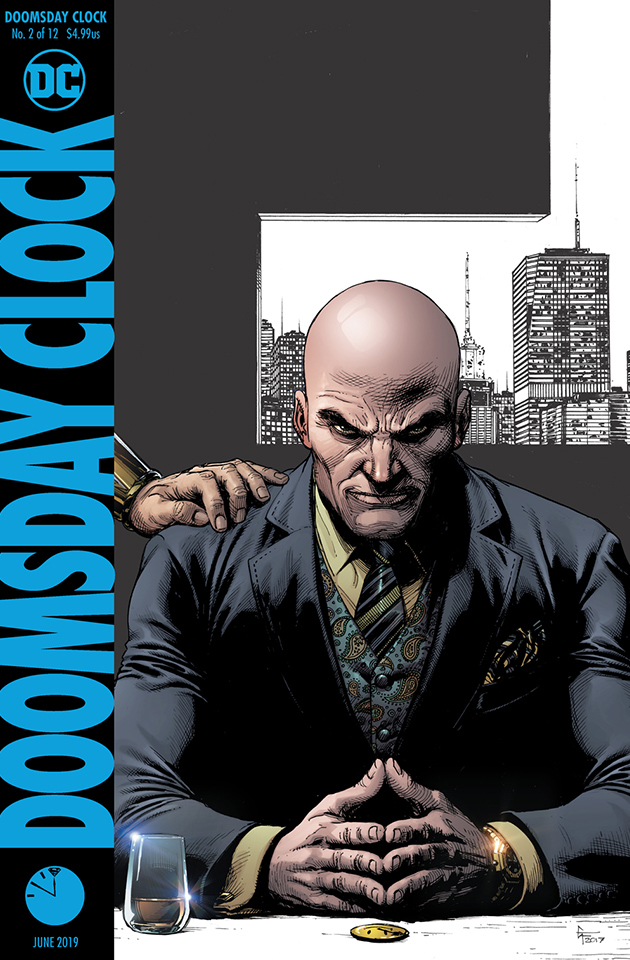

The Owlship crashes in that other world (Dr. Manhattan’s), and Veidt and Rorschach leave Marionette and Mime and go looking for Dr. Manhattan. Veidt goes to see the smartest man, Lex Luthor; Rorschach goes to see the next smartest man, whom he thinks is Bruce Wayne.

Wayne, incidentally, is undergoing psychiatric examination and is shown taking the rorschach test. (A nifty but meaningless gambit.) His dilemma, perhaps, is the same as being explored in Sean Murphy’s Batman White Knight: Gotham is fed up with Batman’s expensive and destructive vigilantism.

Marionette and Mime are on the loose again.

Veidt encounters Luthor but has no luck, particularly, and the interview is cut short by the arrival of the Comedian, who shoots Luthor, perhaps not fatally. The Comedian’s face is scarred but he ain’t dead, so this adventure takes place before his death in Watchmen. But we already knew that.

Or did we? The original Rorschach is dead. So why isn’t the Comedian, whose death began Moore’s Watchmen? Is Doomsday Clock a sequel or a prequel? This sort of puzzle rears its head every once in a while through the series. A head-scratcher.

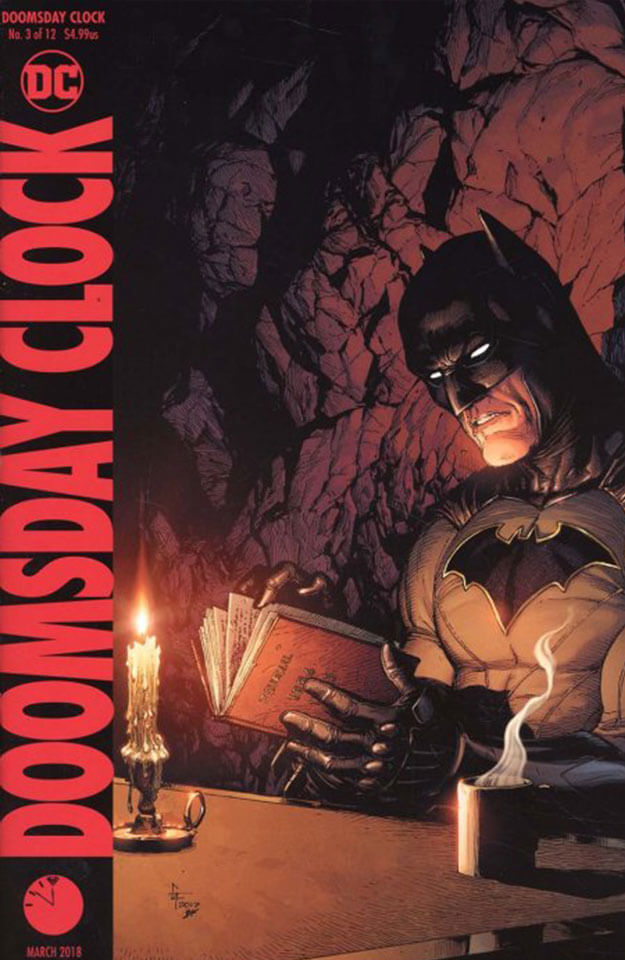

ISSUE NO.3 IS SOMEWHAT MORE CRYPTIC and therefore more baffling than the previous two issues. Rorschach meets Batman and gives him Kovacs’ journal to read, telling him it will explain everything. Batman takes so long reading the journal that he invites Rorschach to spend the night at Wayne Manor. Getting ready for bed, Rorschach takes a shower, and we see that he’s a black guy. Without a name, as far as I know. But I may be missing something.

ISSUE NO.3 IS SOMEWHAT MORE CRYPTIC and therefore more baffling than the previous two issues. Rorschach meets Batman and gives him Kovacs’ journal to read, telling him it will explain everything. Batman takes so long reading the journal that he invites Rorschach to spend the night at Wayne Manor. Getting ready for bed, Rorschach takes a shower, and we see that he’s a black guy. Without a name, as far as I know. But I may be missing something.

The next section of the book focuses on Marionette and Mime as they kill everyone in a seedy bar. Then we’re back with Batman and Rorschach. Batman tells him that after reading Kovacs’ journal, he knows where Dr. Manhattan is, and the two go off into the night to find him. It’s a trick: Batman puts Rorschach behind bars at Arkham Asylum.

The opening sequence in the book continues the confrontation between the Comedian and Ozymandias. Ending the episode, the two fall from great height but, apparently, survive.

None of this seems to make coherent sense. Four episodes, none connected, seemingly, to any of the others. Writer Geoff Johns drops them, one after the other, like the pearls of a necklace without anything stringing them together: each is a separate, apparently disconnected but precious part of a larger narrative, which Johns hints at but doesn’t tell us enough that we can find our way.

And he sprinkles other allusions throughout each of the four episodic scraps. This was Moore’s method in Watchmen although Moore was a little less cryptic.

It’s a risky kind of storytelling. And its success in this case depends entirely upon how dedicated we are to the Watchmen mythos. Are we patient enough to wait around for Johns to pull together all the pieces and present a resolution of sorts that knits them all together?

And how much am I missing because I haven’t read Moore’s Watchmen this year? Are Marionette and Mime people I’m supposed to remember from some previous outing of Moore’s characters? Probably. But I refuse to go back and look at Moore: I think this series ought to stand alone, like any other literary work, and not rely upon other undertakings. Not all works of fiction do this, I realize; but to expect independence is not unreasonable.

The only thing holding this series together so far is the search for Dr. Manhattan. And the slow introduction into Moore’s mythos of the DC universe. We’re had Superman; now Batman. Next, Wonder Woman, no doubt.

Gary Frank’s artwork continues to impress. He is competent beyond mere competence. Where did he come from? Why haven’t I seen him before? Because I haven’t been reading everything that Marvel and DC publish, is why.

He’s a British comic book artist who began drawing comics in 1991 when he was 22, and the next year, he was recruited by Marvel. He went on to draw DC comics and Image titles. In other words, he’s been around for quite some time. I just missed him because I can’t see everything. (I know: you don’t believe it, right?)

Doomsday Clock is worth buying just to see Frank in action. He also does the highly symbolic covers. Otherwise, the only reason to pick up the title is to prolong your bafflement at what is going on.

N0.4 BELONGS ALMOST ENTIRELY to Rorschach—not Walter Kovacs of Moore’s oeuvre but the new Rorschach, who, we learn, is Reggie Long, son of Malcolm Long, who had been studying and befriending Kovacs for quite some time, even while Reggie was a kid. At present, the adult Reggie is imprisoned in Arkham Asylum, where he is interrogated by some professional personage, has hallucinations while being questioned, and is otherwise sometimes pestered by other inmates. Reggie behaves, appropriately enough, like a madman; he is also the narrator, somewhat, of this issue, muttering disconnected fragments of thought.

N0.4 BELONGS ALMOST ENTIRELY to Rorschach—not Walter Kovacs of Moore’s oeuvre but the new Rorschach, who, we learn, is Reggie Long, son of Malcolm Long, who had been studying and befriending Kovacs for quite some time, even while Reggie was a kid. At present, the adult Reggie is imprisoned in Arkham Asylum, where he is interrogated by some professional personage, has hallucinations while being questioned, and is otherwise sometimes pestered by other inmates. Reggie behaves, appropriately enough, like a madman; he is also the narrator, somewhat, of this issue, muttering disconnected fragments of thought.

He either escapes or imagines he does, and he meets Mothman, a naked guy who is flying with the aid of some wings he manufactured. Later on, while he’s still in Arkham (having not, after all, escaped), he escapes again, finds Kovacs’ Rorschach mask and puts it on. Then he heads out across the snowy steppes until joining up with Veidt. The two dress up in warm winter clothing and head out.

The last images in the book are of a mosquito flying toward a hot light bulb and being sizzled by it. This image represents our search for enlightenment: we are drawn to it as a moth is to light.

It’s a dandy metaphor for our engagement with a serial fiction. But, like so much of this series, it doesn’t seem directly connected to any of the events or characters—except, maybe, at the end? In No.12? We’ll see.

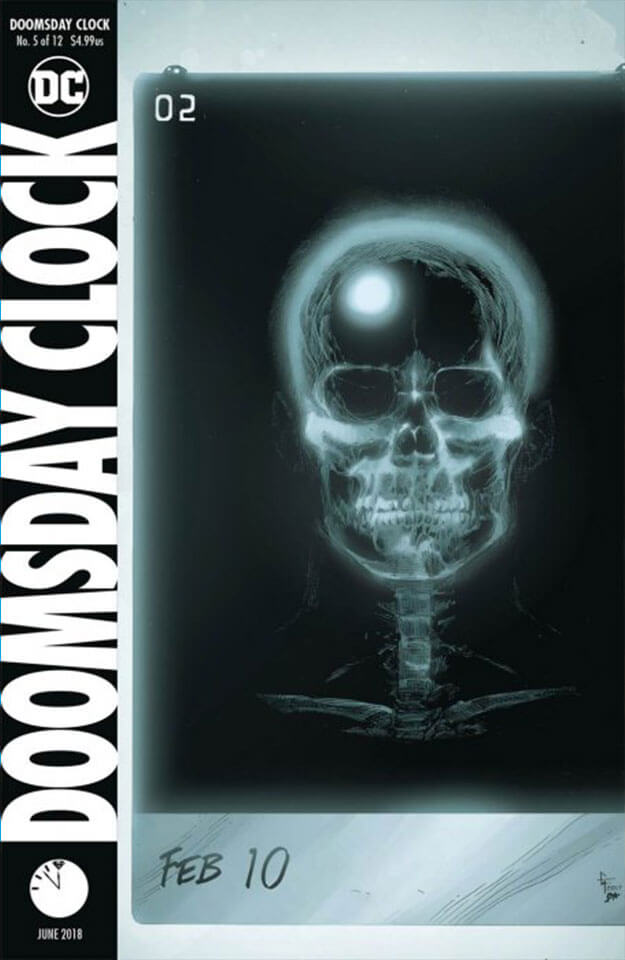

As issue No.5 begins, we see Veidt handcuffed to a hospital bed, under arrest because he tried to kill Lex Luthor while wearing golden pajamas and a purple cape. He tricks the guards into approaching the bed, which enables him to get possession of the handcuff key. In a trice, he’s free and makes his escape wearing the uniform of one of the guards.

As issue No.5 begins, we see Veidt handcuffed to a hospital bed, under arrest because he tried to kill Lex Luthor while wearing golden pajamas and a purple cape. He tricks the guards into approaching the bed, which enables him to get possession of the handcuff key. In a trice, he’s free and makes his escape wearing the uniform of one of the guards.

After a short interlude in the newspaper office with Clark Kent and Lois Lane, we’re back with Reggie Long/Rorschach, who’s joined by Saturn Girl in a search for Dr. Manhattan.

Next, a couple of cops arrest the accountant, Jasper Wellington, of a rich guy named Alastair Tempus, who’s been killed but not by Wellington, who swears he didn’t do it. This page is done in gray, which signals that the sequence is a motion picture staring Carver Colman as Nathaniel Dusk. The continuity leaps into another sequence after showing Wellington on a bus to Pittsburgh (in color—reality again).

Black Adam, a character from Fawcett’s Captain Marvel titles, shows up, radiating evil (as he does in Fawcett), and addresses a growing international crisis by mustering the world’s metahumans (superheroes) in Kahndaq, which, he allows, will serve as a kind of asylum for them during these disturbing times.

In the new sequence, Veidt and Batman are aboard the Owlship. Then we shift to yet another continuity involving the Comedian. The Comedian’s presence in this adventure remains oddly out of sync: he died in the opening pages of Moore’s Watchmen, and if this story is a sequel to Moore’s work, then how can the Comedian be alive?

Just one of many annoying inconsistencies. Will No.12 clear it all up? Dunno.

On the next page, we join the Marionette and Mime, who are trying to find the Joker. Then we’re back with Batman and Veidt in the Owlship; then Jack Ryder witnessing a beheading; then the Owlship; then Lois Lane and Lex Luthor; then Superman.

As you can see, lots of shifting around, each sequence supplying, doubtless, some vital trifle of plot. But it all alludes me.

Then Wellington is pestered by some juvenile delinquents; then we’re back on the Owlship, which crashes almost at once in the middle of Veidt’s boasting about how he improved “his” world. Wellington is attacked some more until the narrative shifts again to Marionette and Mime, who are greeted by the Joker, accompanied by Rorschach who has a Green Lantern. They are all standing over the unconscious body of Batman. A moth hovers hear the hot green light of the Green Lantern.

TO DEPLOY THE INEVITABLE METAPHOR, Doomsday Clock keeps on ticking. With No.6, the series becomes more engaging by revealing the childhoods of Mime and Marionette, how they came together. In retrospect, it is now clear that Mime and Marionette (Marcos Maez and Erika Mason to use their actual names) are not incidental characters in this drama—they are central figures. But it was difficult to discern this as the series chugged along, spewing fragments of some presumably over-arching theme or story which has yet to reveal itself. The Comedian shows up again and does a murderous thing. Otherwise, No.6 belongs to Marionette and Mime.

TO DEPLOY THE INEVITABLE METAPHOR, Doomsday Clock keeps on ticking. With No.6, the series becomes more engaging by revealing the childhoods of Mime and Marionette, how they came together. In retrospect, it is now clear that Mime and Marionette (Marcos Maez and Erika Mason to use their actual names) are not incidental characters in this drama—they are central figures. But it was difficult to discern this as the series chugged along, spewing fragments of some presumably over-arching theme or story which has yet to reveal itself. The Comedian shows up again and does a murderous thing. Otherwise, No.6 belongs to Marionette and Mime.

Before looking at that, however, let me rake over the first five issues again, looking for narrative continuity and picking up a few more stray bits—:

Marionette and Mime (a mute) were introduced in No.1 when Rorschach breaks them out of prison. But then Rorschach takes them to meet Veidt (Ozymandias), who is dying of cancer but wants to find Dr. Manhattan who, Veidt is convinced, can save the world (which Veidt almost destroyed in Moore’s Watchmen, thinking he was saving it from itself).

In ensuing issues, we follow Rorschach through his travails as a madman being treated, and we see him as a youth. Mothman shows up, and Rorschach goes North. We see him in the snow and cold, and he finds Veidt, who is in a hospital, a prisoner. Veidt breaks out, as we’ve seen in No.5.

We start to hear about the metahumans and the Superman Theory—which is that metahumans are a US government project (which the President denies). The epilogue section at the back of the issue lists many of the metahumans. The narrative continues to fragment into shards and shreds without referents. (To jump in here, adding something from the present, post-reading of No.12 rather than the log, the fragmentation is explained in No.12: it’s part of the overall plot and the writer’s scheme.)

And we are assaulted by names the previous narrative leaves mysterious. Jasper Wellington—who’s he? Nathaniel Dusk? Jack Ryder—a missing journalist? (He’s the Creeper, which we discover by reading the fine print. Or by being steeped in DC Universe history.) Firestorm—another metahuman? Who’s the old man who gets a green lantern?

Batman and Veidt go up in the Owlship, and Veidt brags that he has cured famine and disease in his world. What has Batman done in his? Veidt tells Batman that the riots that are in progress in Batman’s world are protests against Batman. The mob trashes the Bat Signal as if confirming Veidt’s theory.

Is writer Geoff Johns tying up some imaginary loose end from Batman White Knight? Why bother? So far, the whole Doomsday Clock dodge is a jumble of loose ends.

Lois meets Luthor, who wants to expose the truth about metahumans, starting by revealing Superman’s secret identity.

The Joker arrives, and Marionette and Mime call him “boss”; Batman lies unconscious at their feet.

That takes us, again, through No.5.

In No.6, the Joker and Marionette and Mime start killing henchmen. The League of Villainy arrives on the scene—Freeze, Riddler, Mirror Master, Sivana (from Fawcett Captain Marvel tales), Typhoon, Moonbeam, Two-Face, Scarecrow—and the Comedian starts shooting and killing them.

In the issue’s longest sequence, we watch young Erika befriend the mute boy Marcos. Thus, the team of Marionette and Mime is formed while they are children, both ridiculed by their playmates. Marionette is the daughter of a puppet-making father named (wanna guess?) Geppetto. Marionette (the puppet, right?) uses strings to kill and dismember foes—the first, the predator cops to whom her father was paying protection. He, Geppetto, hangs himself in humiliation.

Except for such short passing episodes as this, Doomsday Clock is pretty much a hodge-podge of DC heroes putting in cameo appearances. Black Adam saves Jack Ryder. So?

Veidt’s search for Dr. Manhattan is the only continuing thread knitting this episodic and fragmented series together. Veidt and Rorschach and Marionette and Mime are the only characters who appear continually; the rest are all virtually “guest stars,” and they pretty much just come on stage, do some trivial thing, and then leave, all inexplicably.

The faux files at the end of every issue—another copycatting of Moore—eventually explain the Superman Theory, but that seems a decidedly minor strand so far.

Gary Frank’s visuals are superb, and he and Johns demonstrate repeatedly that they know how to manipulate the medium’s resources to tell tales dramatically. Sticking religiously to Moore’s nine-panel grid on virtually every page, the chief means of achieving drama is through the use of intensifying close-ups, at which they are notably adept.

DOOMSDAY CLOCK makes no more sense in Nos.7 - 11 than it has in Nos.1 - 6. The only strand of continuity threaded through the books is still here, and there. Veidt, known by the supermonicker Ozymandias, in No.7 is trying to find Dr. Manhattan (the big, naked blue guy from Alan Moore’s classic, which DC denies by not including any mention of Watchmen in this series) because he thinks only Manhattan can save the earth (which Veidt almost destroyed). Along the way, we encounter various of the DC Universe’s superheroes and superheroines who seem to have no function but to be the villains that governments are hunting to eliminate (because it is suspected that the superfolks are plotting some sort of take-over?). That’s it.

DOOMSDAY CLOCK makes no more sense in Nos.7 - 11 than it has in Nos.1 - 6. The only strand of continuity threaded through the books is still here, and there. Veidt, known by the supermonicker Ozymandias, in No.7 is trying to find Dr. Manhattan (the big, naked blue guy from Alan Moore’s classic, which DC denies by not including any mention of Watchmen in this series) because he thinks only Manhattan can save the earth (which Veidt almost destroyed). Along the way, we encounter various of the DC Universe’s superheroes and superheroines who seem to have no function but to be the villains that governments are hunting to eliminate (because it is suspected that the superfolks are plotting some sort of take-over?). That’s it.

In No.7, Dr. Manhattan shows up but declines to help Veidt. Batman also returns to the story, fights the Marionette to a draw. Also present are the Joker and the Comedian, who’s tied up by the Joker. The Marionette is pregnant. Again. So what happened to her first born? Dunno. Reggie/Rorschach was supposed to find him, remember? It was a condition Marionette put on her coming with Rorschach.

Reggie/Rorschach fights the Joker, leaving him unconscious or dead, prone on the floor, and then takes his rorschach mask off (signaling his retirement?), and Veidt announces that he doesn’t have cancer after all.

If you think this is a fragmented recap thus far, try reading the books.

No.8 begins in the offices of the Daily Planet with Lois Lane and Clark Kent, who are sent to Moscow to report on happenings there. In Moscow, a character named Firestorm, who is actually a meld of two persons—a smart professor, Martin Stein, and a less gifted but athletic teenager, Ronald Raymond—sets enough fires that several dozen people are turned into glass. Putin in Russia declares war on the U.S., and Superman shows up to try to talk him out of it.

No.8 begins in the offices of the Daily Planet with Lois Lane and Clark Kent, who are sent to Moscow to report on happenings there. In Moscow, a character named Firestorm, who is actually a meld of two persons—a smart professor, Martin Stein, and a less gifted but athletic teenager, Ronald Raymond—sets enough fires that several dozen people are turned into glass. Putin in Russia declares war on the U.S., and Superman shows up to try to talk him out of it.

Russian heroes attack Superman and Firestorm, and Superman comes to Firestorm’s aid because he knows Firestorm, properly inspired, can return the glass people to real life. Because he has taken sides as far as the Russians are concerned, Superman forfeits his usual neutrality. He is now the enemy. The glass people are destroyed before Firestorm can act.

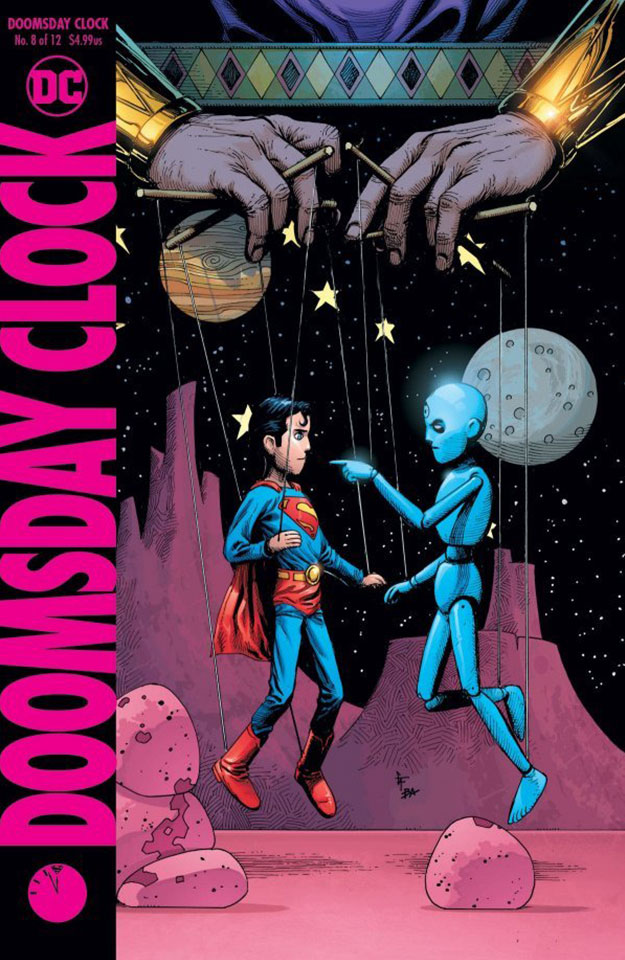

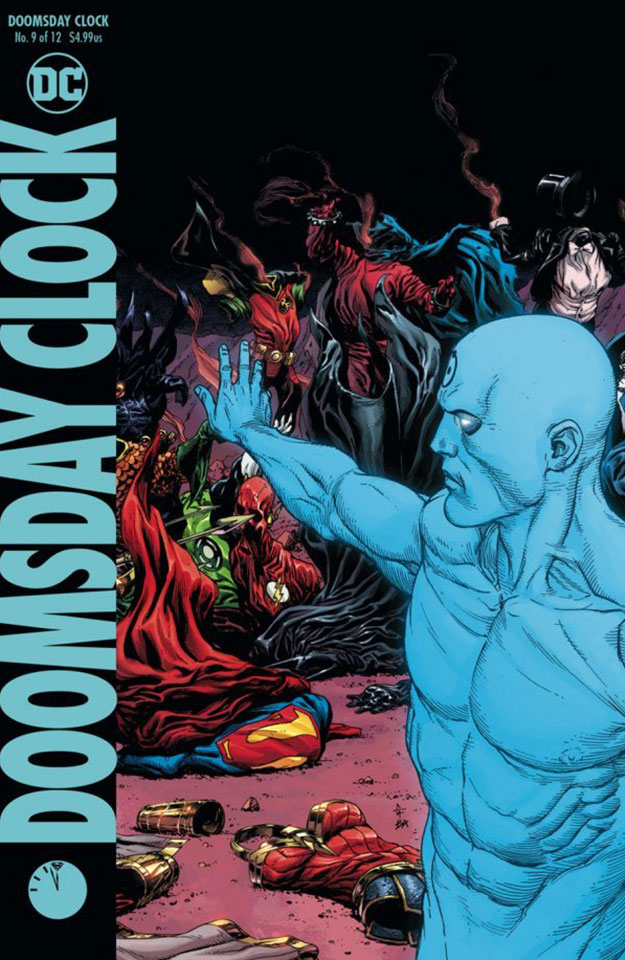

In No.9, Dr. Manhattan takes up the narrative, and most of the issue is devoted to his murmurings (always in blue caption boxes, the color signaling the speaker) and fantastical encounters with members of the Justice League, whom we see in various flying vehicles, a mass exodus that goes on silently for pages. Dr. Manhattan’s utterances also tell us that the narrative is shifting back and forth through Time because each caption starts by citing a date.

In No.9, Dr. Manhattan takes up the narrative, and most of the issue is devoted to his murmurings (always in blue caption boxes, the color signaling the speaker) and fantastical encounters with members of the Justice League, whom we see in various flying vehicles, a mass exodus that goes on silently for pages. Dr. Manhattan’s utterances also tell us that the narrative is shifting back and forth through Time because each caption starts by citing a date.

Dr. Manhattan ponders his present purpose: “Does Superman destroy me ... or do I destroy everything?”

Ah, the plot sharpens and thickens.

In his encounters with DC heroes, Dr. Manhattan always comes out on top—even when it looks as if he’s been disintegrated.

Superman and Batman have both been injured when Firestorm detonates. Then Lex Luthor arrives to “help” Lois as she ministers to and grieves over Superman.

The confusion does not let up a bit in No.10. In fact, it gets even worse because writer Geoff Johns plays with time some more, shifting back and forth, to the past, present, and future. We didn’t know much about what was going on before, and now with the time confusion, we know even less. If I had realized that two DC universes were involved, I’d known better what’s happening; but I didn’t, so confusion reigned.

The confusion does not let up a bit in No.10. In fact, it gets even worse because writer Geoff Johns plays with time some more, shifting back and forth, to the past, present, and future. We didn’t know much about what was going on before, and now with the time confusion, we know even less. If I had realized that two DC universes were involved, I’d known better what’s happening; but I didn’t, so confusion reigned.

Although it might’ve been lessened somewhat had I been paying attention to Dr. Manhattan’s musings on page 14:

A theoretical physicist named Bryce DeWitt hypothesized that the universe was constantly splitting into alternate timelines. The ‘many worlds interpretation.’

It theorized that parallel worlds were endlessly created, flowing out like the branches of a tree. The heroes on this Earth call it the Multiverse.

Later, Dr. Manhattan realizes the universe is all connected to Superman.

Now, the suspense reforms somewhat and begins to make sense.

This issue is mostly about a movie star named Carver Colman, about whom we read in the text/scrapbook appendix to No.3. In this issue, Dr. Manhattan seems to have befriended and helped Colman to stardom. Or is it to death? Why does it matter? Or does it?

At the end of the book, Dr. Manhattan says he’s “a man of inaction”: and he’s “on a collision course with a man of action.” He goes on: “To this universe of hope I have become the villain.”

The issue seems entirely off-narrative. You can read the whole issue and see Veidt or hear what his plans are. (We left him dangling at the end of No.8.)

Gary Frank’s art is still splendid—inspired even. I just hope Johns’ story, however it turns out, is worth all Frank’s brilliant labor. Although now, with only two issues to go, it will take a resolution of superhuman convolution to resolve all the issues and tie up the unraveled ends. Put me down as a doubter.

IN NO.11, we begin with fragments. Batman interrupts a launch, fights some people, and learns that instead of being a knight, he’s a pawn (echoing what Carver Colman said in a Nathaniel Dusk movie in No.10). Then we shift to fight scene starring Wonder Woman, who shows up at last; she’s fighting bad buys from Kahndaq (Saudi Arabia, we learn, thanks to the strategic placement of a map). Black Adam arrives and wants to know which side Wonder Woman is on, Russian or American.

IN NO.11, we begin with fragments. Batman interrupts a launch, fights some people, and learns that instead of being a knight, he’s a pawn (echoing what Carver Colman said in a Nathaniel Dusk movie in No.10). Then we shift to fight scene starring Wonder Woman, who shows up at last; she’s fighting bad buys from Kahndaq (Saudi Arabia, we learn, thanks to the strategic placement of a map). Black Adam arrives and wants to know which side Wonder Woman is on, Russian or American.

Then we see Superman, naked but covered with a blanket, arising from his sick bed and asking for Lois. But she’s having a conversation with Luthor.

Luthor explains: he was recently approached by Veidt who claimed to be from a parallel world that his machinations had all but destroyed (pitting U.S. and Russia against one another in the hope that the world’s population would rise up and stop them both). Veidt tells Luthor that he has come to “this” earth in search of Dr. Manhattan, who Veidt believes has the power to save his, Veidt’s, world.

Nice to have the key motivational aspect of the series explained again, close enough to the end that we can remember it.

Lois and Luthor go on to talk about a mysterious photograph of a man (thought to be Jon—Dr. Manhattan before bluing) and a woman. The photo, Luthor has discovered, has been found in duplicate worldwide, each photo identical to the others.

Meanwhile, the international crisis is taking a more threatening shape. Putin demands that the U.S. turn Superman over to him (so he can punish him for siding with Firestorm), and he is preparing to send his metahumans to America to grab the Man of Steel.

Next is a 4-page Rorschach sequence with Reggie in a cell where he is visited by Wayne’s butler Alfred, bearing pancakes (a reminder of his stay at the Wayne mansion), and Reggie’s long-dead father; Reggie breaks out and runs away, screaming.

In another strand of narrative, Ozymandias is conversing with someone off-camera. He walks by some cells and pauses to interview a woman in a cell. She, it turns out, is Saturn Girl, and she disintegrates when she realizes she’s not part of the timeline in which she is now appearing. (Well, then, why is she there at all? We’re coming up to the end of the 12-issue series, why waste time on characters who aren’t supposed to exist?)

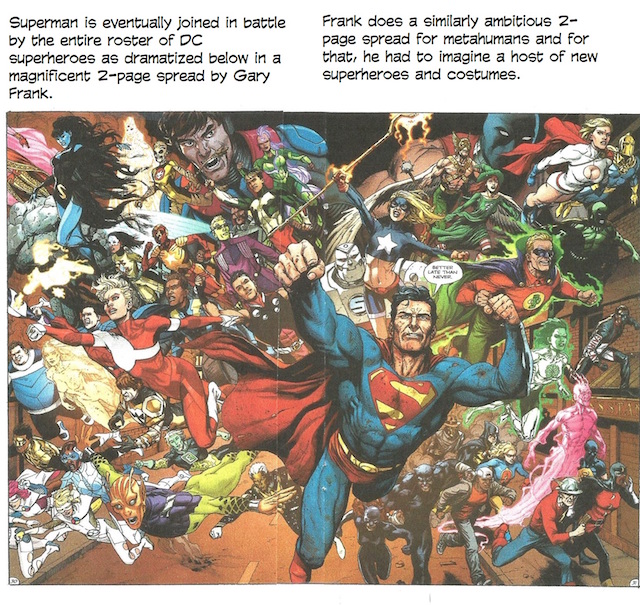

Ozymandias then realizes that one of the parallel worlds Dr. Manhattan visited—ours—is a place of extremes impossible to reconcile, a schizophrenic society overrun with superpowers and costumes. His realization is illustrated by a montage of DC superheroes.

Dr. Manhattan, appearing briefly, believes that his inevitable confrontation with Superman will lead to his (Superman’s? not clear) or his universe’s destruction. Whose? One or the other, it seems, but Ozymandias says he has a new plan to save both worlds so the point, for the nonce, is moot.

In the closing pages, Black Adam leads his band of metahumans onto the White House lawn, whereupon suddenly Superman appears.

And then, apparently, he promptly disappears because in the final two pages, he rockets to that confrontation with Dr. Manhattan, both of them now standing in what appears to be the wreckage of the White House.

And Dr. Manhattan has described himself as a “man of inaction.” So what next?

Presumably, No.11 has set us up for the grand denouement of No.12, just over the horizon. A couple of the questions No.12 must answer—:

The obvious: will Dr. Manhattan, who has disavowed man-of-action status, save the world from itself?

Why is the Comedian still alive?

How do Marionette and Mime (who show up briefly in No.11) figure in the resolution of all this? She was supposed to lead Ozymandias and Rorschach to Dr. Manhattan, but I see little evidence of that role for her thus far.

What is Ozymandias’ “new plan” that will save both worlds? (What if it’s the creation of DC Comics?) (Don’t be silly.) (Why not? Everyone else is.)

Does Doomsday Clock bring the universes of DC and Watchmen together?

IF WE ASSUME—a safe assumption, I think—that Doomsday Clock is supposed to be about the end of the world and how it gets saved and about the DC superhero world and how it absorbs somehow the heroes of Moore’s The Watchmen, then issue No.12 must carry a huge burden of a denouement. And I’m happy to say that Geoff Johns manages it—but it takes him a couple dozen more pages than any of the previous issues of the title. And he still leaves some questions unanswered.

IF WE ASSUME—a safe assumption, I think—that Doomsday Clock is supposed to be about the end of the world and how it gets saved and about the DC superhero world and how it absorbs somehow the heroes of Moore’s The Watchmen, then issue No.12 must carry a huge burden of a denouement. And I’m happy to say that Geoff Johns manages it—but it takes him a couple dozen more pages than any of the previous issues of the title. And he still leaves some questions unanswered.

No.12 is divided into two narratives. One involves Superman and the confrontation with Dr. Manhattan promised in No.11. The other focuses on Ozymandias and how he manipulates events to suit his purposes. Both narrative strands thread their way to the end of the world, which brings the two together.

Rorschach/Reggie figures in the Ozymandias thread. Alfred urges Reggie to don the Rorschach mask again so he can lead us to Ozymandias “before it is too late.” Batman also urges him to do so (resulting in a scene in which one “mask” is telling the other “mask” what to do with his mask). Reggie finally puts on the Rorschach mask—and the world ends. For several pages of black panels.

In the Superman/Dr. Manhattan narrative, Superman fights a swarm of metahumans (some, from Kahndaq, led by Black Adam) who have been sent to take him to Russia to face punishment for siding with Firestorm.

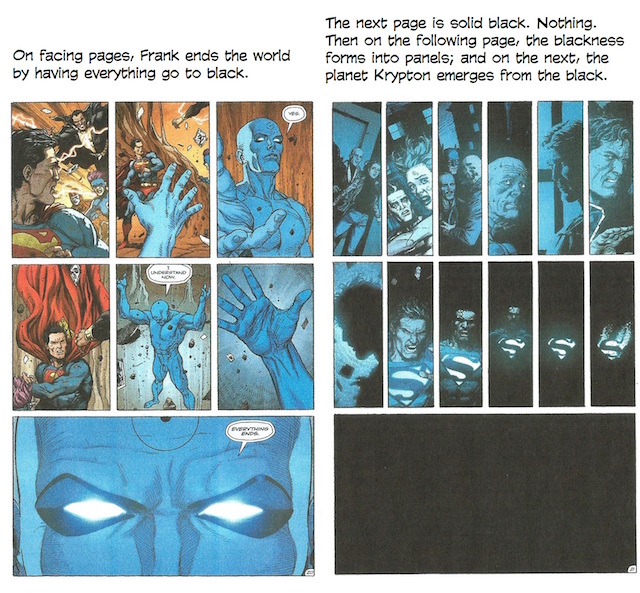

Single panels depicting his struggles are sprinkled among the panels otherwise devoted to Dr. Manhattan’s thoughts and wanderings. Dr. Manhattan muses about the future but refuses when Superman asks for help to help him. Finally, Superman, exhausted, says he can’t do it alone. Dr. Manhattan still refuses to join in.

But then Superman saves Dr. Manhattan from an attack by one of the metaphumans, perhaps Pozhar (a Russian metahuman?).

Dr. Manhattan is puzzled:

“Why would you defend me?” he asks Superman.

And then, watching DC heroes band together behind Superman, Dr. Manhattan says, “I understand now.”

And later, after the end of the world has been resolved, he adds: “I see tomorrow. The Man of Tomorrow. And for the first time, I am inspired.”

Dr. Manhattan, who is usually indifferent to emotion, suddenly—inspired by Superman’s struggle— feels something. Inspiration.

THROUGHOUT THE BOOK, much of which is narrated by Dr. Manhattan, time is continually shifting, back and forth. The comics format is perfectly suited to presenting this phenomena: successive panels present aspects of different times.

“Superman’s timeline shifts forward and Reality divides for the first time, creating the multiverse.”

The more shifts, the more Earths, each one with its own band of superheroes who look like the superheroes of all other Earths, and so “every era of Superman is preserved.”

Dr. Manhattan concludes: “No matter how many times Superman’s existence is attacked, he will survive—even if change is a constant— because hope is the north star of the metaverse.”

After the end of the world (artfully represented by a few pages of nothing but black panels), it starts over again. Krypton implodes. A rocket carries Kal to Earth, where he is found by the Kents.

Dr. Manhattan reflects on all this: “The rocket arrives. A child is loved. Superman is made. I now understand Superman’s true purpose. He will show them the way. And in a millennium, when his timeline converges with the Legion’s ... humankind will finally embrace the ways of Superman. He is the bridge stretching across generations that will lead everyone to peace.”

The “ways of Superman” are to do Right and fight Wrong.

“I believe in wishes again,” Dr. Manhattan says. “Destiny is not without a guiding hand.”

He recalls Janey, his fiancee when he was disintegrated by the Test Chamber and reformed into a naked blue man.

“Life doesn’t stop,” he murmurs to himself, remembering the Kents and the infant Clark and Janey no doubt. “But it needs love.”

The Superman/Dr. Manhattan confrontation narrative ends with Superman’s victory: his ways are adopted by Dr. Manhattan, who realizes Superman is better than he: “I can never be the hero this world needs.”

And with that, Watchmen and its heroes are denied entrance into the DC firmament: DC will go on without any of Moore’s heroes.

In one of the book’s last scenes, Johns brings together Dr. Manhattan, the Comedian, Marionette, Mime, Reggie/Rorschack, and Ozymandias, arrayed across the page in a single panel, all facing Dr. Manhattan. A confrontation.

Dr. Manhattan says he knows what Ozymandias has done, he says, and Ozymandias says:

“If I couldn’t convince you to use your powers to save our world, I was certain Superman would. All I had to do was arrange the confrontation” (i.e., his “new plan”).

“Everyone lives today,” he concludes.

And then the Comedian shoots him.

But the Comedian is then disintegrated by Lex Luthor and one of his machines and sent elsewhere—to Watchmen: we see the Comedian falling to his death, the opening gambit of Moore’s tale.

One of our questions is answered: the Comedian can show up in Johns’ narrative because of the time shifts. Sometimes he’s present as a prequel; other times, his presence is a sequel.

Then the Reggie/Rorschach thread unravels.

A soon as Ozymandias falls, wounded, perhaps fatally, Reggie pounces on him, swearing to stop the bleeding and save Ozymandias’ life so he can “pay for his crimes ... and rot in prison.”

So Reggie becomes an avenging angel.

At the end of the book, other stray bits are resolved. Carter Colman is instrumental in getting homosexuality removed from the American Psychiatric Association’s diagnostic manual of mental disorders. The metahumans are brought under control in order to study them.

Marionette and Mime, despite their bloodthirsty history of killing people, are spared. “As cruel and callous as Erika Manson and Marcos Maez can be, the love between them is real.”

So love saves them. And Erika gives birth to another child, a girl.

Meanwhile, Dr. Manhattan raises a boy from infancy and gives him the last of his powers. And later, the boy goes knocking at the door of the Hollis family, whose daughter, Sally, opens the door and finds the boy standing there, saying, “A friend of your mom and dad’s brought me here. He said they’d know what to do.”

When Sally asks his name, he responds: “Jon called me Clark.”

And he’s got Dr. Manhattan’s forehead circle on his forehead.

And so it begins anew? Again?

No.12 closes with a quote from Tagore: “Every child comes with the message that God is not yet discouraged of man.”

One of the canniest maneuvers of Christianity is its beginning with the birth of a child: everyone loves an infant.

Below Tagore’s remark is the doomsday clock with its hand turned back to the beginning, represented by Superman’s chest insignia.

And on the very last page, we see Carver Colman’s star on Hollywood’s walk of fame.

A FEW DOZEN SHREDS AND PATCHES and their interrelationships I won’t even attempt to explain. For instance, a ring. What does it mean? And who are the Hollises?

I’ll leave those and other similar fragments to literary scholars.

Some of the unexplained bits reflect only the tricks of fictional narrative: episodes and incidents unrelated to each other or to the over-arching theme of the work exist in fiction as a spur to reader interest, keeping us going and engaged. Hence, many of the so-called “puzzles” I simply overlook for now, sticking to the main themes as revealed in No.12.

But we must address the questions I posed after No.11, the ones not yet answered:

Dr. Manhattan remains a “man of inaction” throughout Superman’s fights. But after that, he takes some actions. He raises a child. And he arranges for the disappearance of all nuclear weapons, worldwide.

Marionette and Mime find happiness of a sort. But I still haven’t seen evidence that she lead Ozymandias and Rorschach to Dr. Manhattan. So why, after all, is this couple in this book? (See “tricks of fictional narrative” above).

Johns has performed a heroic task in winding up this tale as he did. But then, the device by which he accomplishes this ending can be handily adapted to resolve any seeming impossible situation: Time shifts. Multiverse. Time and place are tools.

By shifting time back and forth, Johns destroys our reality, which is subsumed under another, a multiverse in which Superman reigns morally. Loose ends don’t matter: they can be shoved aside as part of another time shift.

Superman’s world(s) are good because he does what’s right. They are not evil—nor indifferent as is Dr. Manhattan's.

By multiplying earths and slipping time, Johns can make Superman the champion of “good” everywhere. He can discredit Dr. Manhattan and retire him (ditto Moore’s heroes). Superman reigns.

Thus, in the struggle between Moore’s fictional world and DC’s, the latter emerges as morally superior. Doomsday Clock, then, does not integrate Moore’s world with DC’s. At the end, only DC’s world remains, altered somewhat, perhaps, by Dr. Manhattan/Geoff Johns’ time shifts.

Johns is interested more in outcomes than in the processes by which we arrive at the outcome. At least, as a writer of this book that’s doubtless how he operates. By destroying “reality” with time shifts and multiverses, he can glide by processes, ignore everyday realities (and even plot wrinkles), and focus on the outcome.

But he doesn’t entirely ignore reality. In fact, he alludes to our present-day predicament via this Reggie/Rorschach monologue: “The world is drowning in hate and anger. Sides separated by an ever-widening canyon of digital bile. Soon both factions will tumble off edge, falling into bottomless pit of liberal self-righteousness and outdated identity politics ...

“Hands clutching their weaponized phones, finding no olive branch to save them because neither side knows what that means anymore.”

“Digital bile,” nicely put.

This is how Reggie sees the world and why he resists those who urge him to try to change it. “Why not let this ugly world destroy itself?” he asks. But in the end, he chooses to help: he opts to get Ozymandias punished.

Even Superman muses about our polarized world: “The world’s more connected than ever but it’s never been so divided.”

At the end, Dr. Manhattan recommends ending polarization by “stopping to smell the roses.”

That’s scarcely the only aged bromide Johns offers. He also remarks that “its not whether you win or lose but how you play the game.”

You play the game by doing what’s right. And what is right above all other rights is to love one another.

After the inevitable graphic novel version of this tale is published, DC may have another perennial best seller on its hands. Another Watchmen. Literary scholars could keep assigning it to their English classes, where students will buy it regularly, in class-size quantities, for as long as literary scholars persist.

It reminds me of what James Joyce is said to have remarked about Ulysses (or was it Finnegans Wake?):

“If my book makes it onto reading lists in American colleges, my fortune is made and my future assured.”