Originally published in The Comics Journal 128, 1989.

Originally published in The Comics Journal 128, 1989.

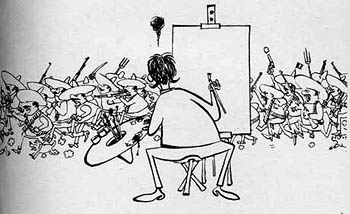

If you point out to Sergio Aragones that he's one of the most recognizable cartoonists in the world, he has a typically modest comeback. It goes something like this: In the first 20 years of his cartooning career, he did not have any continuing characters. Therefore, he started using his self-caricature as a recurring motif, and MAD readers around the world became familiar with his smiling, broad-shouldered, strong-jawed, and extravagantly-moustachioed figure.

While Aragones's distinctive physique is certainly an asset in this regard, the fact that he is recognized everywhere he goes is more likely because he's been everywhere and done everything — including making regular appearances on two TV shows [Laugh-In and Speak Up, America). When you add to this that he's one of the most prolific and brilliant cartoonists of his generation, and one of the world's true gentlemen to boot, you begin to realize that Aragones' recognition is fully earned. He deserves to be a celebrity.

Aragones' tumultuous early days — born in Spain in 1937, brought up in France and Mexico — made him bilingual virtually from birth and instilled in him a cosmopolitan spirit that would flower when he reached adulthood. After an erratic but not unsuccessful career as a cartoonist in Mexico during the '50s, Aragones set off to New York in quest of fame and fortune in 1962. It was only a few months before he hooked up with the cartooning royalty of the day: MAD. He immediately became a staple of the magazine, and has not missed an issue in 27 years; he remains (along with Don Martin) the most widely-known MAD staffer.

Aragones' involvement with comic books, on the other hand, has been a lot more variegated. In 1967, he stumbled into the job as a writer/plotter for DC Comics, working on a number of little-remembered titles (Jerry Lewis, Angel and the Ape, and various anthology books) in addition to creating the legendary Bat Lash. But his idiosyncratic command of English (which persists to this day) kept him away from full scripting chores, and his cartoon style was hard to place in a field that seemed to have turned its back on humor. Typically, Aragones cut his own path, supplying DC with short humor pieces (including the award-winning "The Poster Plague," scripted by Steve Skeates). This culminated in his 1973 co-creation of the humor comic Plop! — one of the few bright spots in '70s mainstream comics. When the copyright laws were changed in the late '70s and comics publishers retaliated with the implementation of the infamous work-for-hire contract, Aragones was part of a wave of cartoonists who left the field in disgust. He turned up here and there — as writer/artist on the detective series T.C. Mars (created for Joe Kubert's ambitious but ephemeral Sojourn), as plotter/co-creator on Steve Leialoha's rabbit series for Star*Reach's Quack! — but it took the alternative comics explosion of the early '80s to lure him back into the comic book vineyards on a permanent basis.

If anything has occupied Aragones' attention during the past decade, it's been Groo the Wanderer. With a fine sense of occasion, Aragones premiered his catastrophically boneheaded barbarian in 1982 in Destroyer Duck, the benefit comic created to aid Steve Gerber in his lawsuit against Marvel Comics over the ownership of Howard the Duck. Groo then moved to just-formed Pacific Comics, loyally sticking around until the company's collapse and then, after a brief second stopover at Eclipse, ending up in Marvel's Epic department, where it became the first creator-owned comic distributed to the general newsstand market — only a few years after Aragones had been told in no uncertain terms by "that tall fellow" (as he calls former Marvel Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter) that Marvel would never, could never allow creators to maintain ownership of their work. Holding out had paid off. If Groo is a Marvel comic now, it is in name only. Aragones and his oft-plugged co-conspirators — letterer Stan Sakai, colorist Tom Luth, and scripter/edit/elucidator Mark Evanier — run the comic like a mini-fiefdom. Every month they send a complete issue to the Epic offices (courteously leaving an inch at the bottom of the first page for Marvel to strip in the names of whichever three editors are in charge at the time) and every month it gets printed as is. Unsurprisingly, it's one of the very few late-'80s Marvel comics to show any quality, verve, or individuality.

Countless jokes have been made about Aragones' shaky command of English (which, it should be pointed out, is his third language, after all). "Command" may be a misnomer: Aragones sometimes appears subordinated to the torrent of words that flows from him. Yet this does not stop him from being one of comics' great conversationalists — articulate, funny, opinionated, and possessed of a limitless supply of marvelous anecdotes. After a few minutes, the listener becomes so accustomed to the random distribution of prepositions, the hit-and-miss approach to tenses, and, most of all, the majestic accent that 25 years of life in the United States could not muffle, that he begins to believe this is the only way English should be spoken.

Reading it, however, is another story. After Robert Boyd painstakingly transcribed the interview, the job of taming Aragones' speech fell to interviewer Kim Thompson. "The irony of this," Kim notes, "is that Sergio's speech is so much more expressive in its original form. I think of him as the Picasso of public speaking: the eyes are drawn on the same side of the face, the arms are connected to the neck... but, by God, it all makes perfect sense!" Nevertheless, the editors conferred and decided that 20-odd pages of this near-Joycean palaver might strain a less poetically-minded reader's patience. So Kim (whose last interview for the Journal, with Moebius in issue #118, was conducted entirely in French) went through the three-hour conversation and wove the verbal strands into more traditional, if less creative, patterns — which Aragones then vetted, clearing away the occasional snarls that had resisted Thompson's attempts at domestication.

Cartoonist, scripter, animator, actor, mime, stuntperson, photographer, explorer, sculptor, raconteur, prankster, and polyglot — a lot of words describe Sergio Aragones. Here, now, are a few of his.

A Cosmopolitan Childhood

KIM THOMPSON: You were born in Spain.

SERGIO ARAGONES: I was born in Spain, in 1937. This was during the war. My father had been fighting Franco, behind the lines. From Spain we moved to France. I don't remember anything, but —

THOMPSON: How old were you when you left?

ARAGONES: I left there when I was six months old.

THOMPSON: And you took your family with you. [Laughter]

ARAGONES: I took my family with me. In those times — we're talking '38 now — they had what's called the Vichy section of France. That's where they sent all the Jewish kids and the people from Paris, and they accepted a lot of Spanish refugees: that's where we were. What happened is that after a while there was trouble: the food was scarce, so they started getting rid of the refugees because they needed it for themselves. By then, Mexico had opened its arms to the Spanish refugees from the civil war, so we went to Casablanca, like in the movie — the advantage was, we had tickets reserved on a ship — and from there we went to Mexico. I was raised in Mexico. When we arrived there I didn't speak Spanish, I spoke French. In my early years my parents had figured out I'd have plenty of time to learn Spanish when I was in Mexico, so when I was in France, I went to a French kindergarten. So I learned French before I learned Spanish.

THOMPSON: I went to French kindergarten, too.

ARAGONES: I got to wear those little robes. There was a 1960s movie called The Two of Us, about a Jewish kid who is sent from Paris to this man who hates Jews, and he ends up loving the kid very much. It was very strange because I was looking at the movie and — there I am. The same haircut, the same uniform, the little robes that you wear. The curious thing is that during the movie, when the kids entered class... before class started you would sing a song that went, "0 Marechal, nous voulons..." — that was Marshal Petain's song that you had to sing. A hymn to the Vichy government. And I started singing it in the movie house!

THOMPSON: You still remember the words?

ARAGONES: No, no, I don't remember the lyrics now, but I did then, in the movie house. I was singing with the other kids. It was very strange, very.,. doo-doo doo-doo, doo-doo doo-doo — Twilight Zone time. When I arrived in Mexico, I was integrated immediately — even though I didn't have too many friends because I had just arrived. You're the new kid and you have an accent. I've always had an accent. [Laughter] As a little kid, 1 had a French accent. When the other kids make fun of you, you don't want to get out of the house. So you stay at home and what do you do? You take pencils and start drawing.

THOMPSON: So you drew from the time you were a little kid?

ARAGONES: Oh, yes. I was never a good artist. I was just a drawer. I was always drawing. I was the guy who told stories to himself, but drew at the same time. When I look at drawings by kids, they are very orderly. Mine were not. In one sheet I would tell a whole story, but it wasn't in order. I'd be drawing on top of a drawing on top of a drawing — all over. Once I saw my first comic, that's when I realized there was a continuity in the drawing.

THOMPSON: Put them one after another.

ARAGONES: Put them one after another. And I remember my first comics. I even remember the first comics I saw in English. I was in the second grade and some kid brought some comics in color. I had seen Spanish comics, black-and-white comics, but this was so extraordinary — to the point that we were on a break during class and I started just looking at the pictures and I forgot to go back to class. And when the school day ended, I was sitting on the tree in the back of the school just looking at these two comics. It wasn't even a lot of them, just two. It was a total discovery.

THOMPSON: Do you remember what the comics were?

ARAGONES: No, but I know if I see them, I would recognize them immediately.

THOMPSON: Do you ever go to conventions looking through back issues just thinking that one day...?

ARAGONES: No, no. I didn't know comics as comics back then. Everything was in the same category: comic strips, cartoons. When I was a kid, my parents belonged to an association called La Casa Valencia — this was all the people from Valencia, where I was born. All the refugees went there once a week to talk and to make plans for when they were going back. The meeting hall was on top of a movie theater that only showed cartoons. So my parents would drop me off there, go to the meeting, and they knew I was not going to get bored no matter how many times I saw the program — so the program would go once, twice, three times, and they would come pick me up and take me home. To me those were the best times. And I saw cartoons over and over and over.

THOMPSON: I assume those were American cartoons.

ARAGONES: Yes. The classic Tom and Jerrys, early Koko the Clowns, everything. We're still talking the '40s. So I grew up with animation, and with the comic strips that were translated from English to Spanish. There weren't that many comic books — we had some of the Mexican ones — so I didn't really grow up with comic books. But in that time anything that had color really fascinated me. And then, when I could read better, then I started discovering comics.

THOMPSON: When you watched cartoons or read comics, did you try to draw like them? Or was all your drawing out of your head?

ARAGONES: No, it was always out of my head. I never drew cartoons — it was adventures. I enjoyed animation, I enjoyed comics, but I never thought that was what I wanted to do, nor how they did it. I enjoyed the content of the cartoon more than the drawing itself. I enjoyed the punchlines and I enjoyed the gags and I enjoyed what they had to say. I was a reader. I read words more than anything. So it was a mixture of everything. But, no, all my early drawings were little adventures. Badly drawn, because

I didn't really care very much about the drawing itself. So I don't have very clever drawings from when I was a kid. There was always somebody who could draw better than me. I was never called the artist of the class. I was always being chastised by the teacher because I was always drawing, but I was not the guy who drew well — until about the third grade. Then I realized I had a facility to draw whatever I wanted. The earliest money I ever made was with drawings. At the time, the education in Mexico was all based on memory. You'd get to class and the teacher would say, "Memorize this!"

THOMPSON: A very European way of learning.

ARAGONES: Yes, and at the end of a year, you knew everything because you had memorized it; education was very strong. I remember, in the third grade we had one book for everything. One chapter was history, one chapter was geography, one chapter was natural history, botany, and so on. The teacher would give us homework, which would consist in copying Chapter Eleven, including the illustrations, which we'd have to copy from the book — like a beetle or a plant, the pistil of a flower, or soldiers — that type of thing. All the kids who couldn't draw would leave a square where the drawing as, and I would charge them to draw that. The equivalent of a few pennies. I would sit there before class doing this. That's probably why I draw fast — because I drew so many of them. I made enough money to buy a game — a bullfighting game, little bullfighters and little bulls and stuff, and when I went with my own money and bought it, my mother wanted me to return it because it was so expensive! And then, of course, the teacher found out and that was the end of it.

THOMPSON: Did he notice that all the kids were drawing in the same style?

ARAGONES: I don't think the teacher ever read them because they were just copied from the book. So that was my first money I ever made — with drawings. I remember when I went to my house from the elementary school by bus, I was one of the last ones to get out of the bus. So I would sit there and tell stories to the kids all around me, and the next day I would continue them. I was creating them as I was going along.

The Burgeoning Cartoonist

THOMPSON: I understand that your first professional sale was sort of made for you.

ARAGONES: That was in high school. By then, I was already drawing gags. Slowly I'd started discovering how funny the comic strips and the gags were. By the end of the elementary school, I'd started making little gags and little cartoons; so when I entered high school, I already had a sense of cartooning. What most impressed me — I think I wanted to become a professional cartoonist because of Virgil Partch [VIP]. Because all the cartoons were sort of the same, and suddenly this man came along, drawing both eyes on one side of the face and pointed noses and lines that continued in a roll, as if he didn't know how to draw. But he knew how to draw; he was sensational! Virgil Partch was a big discovery for me.

THOMPSON: He was appearing in Mexican magazines?

ARAGONES: No, I would go to places where they had magazines from all over the world, including the United States. One of the magazines, called Ja Ja — the one my first sales were made to — had published syndicated gags. In '53, we had a mural newspaper at school. In those times we didn't know what Xerox was, we had a thing called mimeograph. And the mimeograph was messy, you had to turn this crank — so instead of using a mimeograph, we had a mural newspaper. It was in a big glass box on the wall for people to read; all the articles were there, and the cartoons that I did. The editor was a girl, one of my classmates, and she would tell me, "Sergi, sell them to magazines." To me, that was the most absurd idea — sell my cartoons. And one day she said, "We're having lunch, all of us. Sergi's inviting us." I said, "I don't have the money." She said, "Oh, yes you have. You've just sold these cartoons." She had sold three cartoons from the wall to this magazine called Ja Ja, and that was my first professional sale — in 1953. I was more surprised than anybody else. Now I was a cartoonist. Of course, what happened is that once I started going there nobody wanted to buy my stuff. [Laughter] I wasn't good enough yet. They'd just needed some cartoons that day. But once you see your cartoons in print, it makes you want to become a cartoonist.

THOMPSON: The bug bites you.

ARAGONES: Yeah, you start looking at cartoons in a different way. Suddenly you are looking at not what's in them but how the cartoonists did it, which I never had paid attention to before. When I finished high school, there weren't that many magazines you could submit cartoons to. Ja Ja was probably the only one that was accessible to younger cartoonists. Through a roundabout way I met another Mexican cartoonist who wanted to start a magazine. I didn't know how to ink, so I would draw the cartoons in pencil and be told, "No! No! No! This is how you ink it!" I hated working with a brush. It was such a complex thing. I'd never studied art — I just wanted to tell the joke as fast as I could. Anyway, we started the magazine, which was called Sic. It was very small; we printed it at home. It included a lot of cartoons from the United States that we'd ripped out — ripped off. It was very amateurish, but we tried. That was in '54. And then I entered college in '55.1 entered engineering school because my parents wanted me to be an engineer. It sounded good, you know? When you come from a European family, you have to have a degree, and my family had always wanted to have an engineer at home. [Laughter].

THOMPSON: Never know when you can use one.

ARAGONES: "What do you want to be?" "An engineer!" "My son is going to be an engineer!" And then I went to engineering school, and I sat there and didn't understand one word. College is different from high school, totally different. Teachers don't care about you. They just go to teach and if you pay attention, good; if not, that's your problem. And so I was sitting there, class after class, and I didn't understand one word of it. Class after class! And I said, look, this is not what I want. I didn't want to be an engineer. I wanted to have fun. Now, there's no such thing as a generic Bachelor of Arts degree in Mexico. You have to be something: an architect, a doctor. By then, I'd been through high school — what's called la preparatoria — which is definitively career-oriented — so to be something else, I had to take it over. So in '55, I spent a whole year in high school taking courses to get the credits I needed to go into architecture. And it was very good because I could do a lot of cartoon work. So I went to different magazines, did a lot of research on cartooning.

An Argentinian guy came to see us who wanted to open a syndicate; we gave him our cartoons and, of course, we never saw him again. That kind of thing happens when you are a very young cartoonist. I did the rounds at different magazines and I wasn't really good enough to make any more sales. And the pay in those times was very bad.

Ja Ja paid one dollar per cartoon for reprint fees, and that's what we got. Because for them our material was not important. So there wasn't enough money in it.

Then, once I entered architectural college, I didn't have much time to sell that many cartoons because now I had to pay attention to class. I was doing also what I did in high school, however: a mural newspaper. But this one was all me. I would come in in the morning and I'd have this large sheet of paper, and everybody who needed something to be said to the class would tell it to me and I would do a cartoon about it: "There is a basketball game against the Medicine School" or "The teacher is changing this class" — that kind of thing. Within half an hour I would have drawn up this gigantic board, the size of an architectural drawing, with a big magic marker. I'd finish it up and put it on the wall, and all the kids would look at it. After the third one, it didn't last a minute. Everybody wanted the cartoons, so they stole it. So they gave me a special glass case for it. I had to do a lot of them, and I had to do them fast so that I wouldn't miss class. I think that's what the speed comes out of.

That was more or less how I spent those early years: a lot of cartoons sold to magazines — and a lot of bartering, too. I'd get haircuts for drawing signs for the barber, or draw signs for supermarkets, things like that. I'd make a lot of sales at Christmas. I would draw tons of Santa Clauses on windows with water-based colors. On El Dia de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, all the bread stores sold special bread on that day, so they'd draw skeletons on their windows — I drew a lot of those, too. It was a lot of fun, but also, how do you say, hard knock...?

THOMPSON: You paid your dues.

ARAGONES: Yeah.

THOMPSON: So how come you didn't end up as an architect?

ARAGONES: Well, I was a goof-off. I spent a lot of time in the swimming pool, doing aquatic ballet, and I was doing my cartoons. Architecture was fun until it became too technical. I liked it a whole lot the first three years. I liked creating the designs but when we got into the cost of materials and weights and loads and stuff, it was, "For heaven's sake, what am I doing here? Back to engineering school!" I didn't want to spend my life dealing with workers, working out prices, and stuff. By then. I'd really decided I didn't want to be an architect. I just continued going to school because I couldn't make a living as a cartoonist and I couldn't get a job at anything else because I didn't like anything else. That meant I'd have to leave home. So I continued architecture school so I could live at home! [Laughter] I stayed there for a long time.

I had a lot of different jobs. I worked as a draftsman for a company, doing plans. This was in '57, and by then I had a weekly page in Manana magazine. It was one of the magazines where you'd drop by to see if they wanted your cartoons, and they said, "O.K., bring us five every week." So I got a weekly page! And I did what I'm doing now with MAD: every week I would pick a subject and do five gags about it. It was very spontaneous type of thing, like a newspaper. I would go up to the magazine every week, I would sit in that office, do the cartoons, leave them there, and that was the job. But that pay was also very minimal.

By now, I was very aware of American cartoons. And the whole thing started when I was sitting in the cafeteria in college. I was discussing with other people the idea that there should be degrees in cartooning — because in Latin America, as in Europe, it's very important to have a- degree in front of your name. When you grow up in that culture, you realize you're not going to be "Dr. Cartoonist" or "Architect Cartoonist." It would be ludicrous. So we decided there should be a college for different careers — like cartooning, taxi-driving. So we thought out a college curriculum for taxi drivers — you have to learn all the streets in the city; medicine, if somebody gets sick in your taxi cab; languages, to be polite. A very serious curriculum. And if you were a taxi driver you'd have a degree in front of your name and people would treat you with respect. And we came up with a curriculum for every career, even shoe-shining — manufacture, different types of leather. So when the subject of cartooning came up, I sort of made myself a curriculum. And one of the things was to spend one year in Europe to study humor without words, which is what I was doing; another was to go to the United States to study merchandising, how to get to the people. Because in Europe circulations were lower than in the United States, and it was a lot harder communicating with the United States, where the circulations were higher and you could reach a lot of people. And I thought, "this makes a lot of sense. I'm going to do it. And after a few years, I'll be a really good cartoonist, because I'm going to follow this curriculum." I was going to go to Europe, but my friend couldn't go, and I found out what they paid for cartoons in the United States. So I took a bus and went to New York.

By now, I was very aware of American cartoons. And the whole thing started when I was sitting in the cafeteria in college. I was discussing with other people the idea that there should be degrees in cartooning — because in Latin America, as in Europe, it's very important to have a- degree in front of your name. When you grow up in that culture, you realize you're not going to be "Dr. Cartoonist" or "Architect Cartoonist." It would be ludicrous. So we decided there should be a college for different careers — like cartooning, taxi-driving. So we thought out a college curriculum for taxi drivers — you have to learn all the streets in the city; medicine, if somebody gets sick in your taxi cab; languages, to be polite. A very serious curriculum. And if you were a taxi driver you'd have a degree in front of your name and people would treat you with respect. And we came up with a curriculum for every career, even shoe-shining — manufacture, different types of leather. So when the subject of cartooning came up, I sort of made myself a curriculum. And one of the things was to spend one year in Europe to study humor without words, which is what I was doing; another was to go to the United States to study merchandising, how to get to the people. Because in Europe circulations were lower than in the United States, and it was a lot harder communicating with the United States, where the circulations were higher and you could reach a lot of people. And I thought, "this makes a lot of sense. I'm going to do it. And after a few years, I'll be a really good cartoonist, because I'm going to follow this curriculum." I was going to go to Europe, but my friend couldn't go, and I found out what they paid for cartoons in the United States. So I took a bus and went to New York.