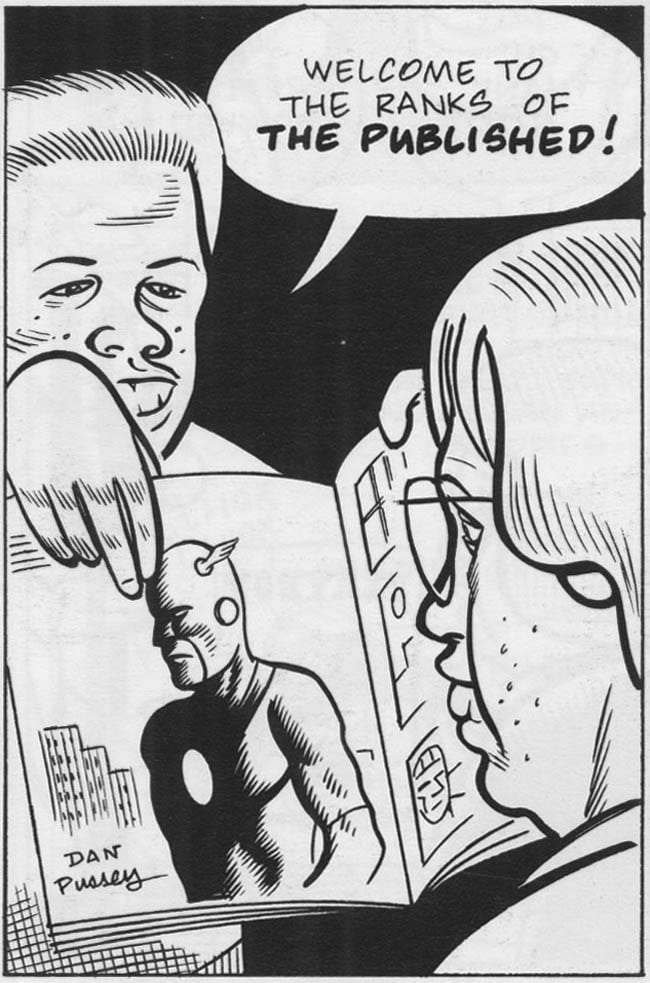

Daniel Clowes is inarguably among the greatest living cartoonists. Two decades ago, his work in Eightball was already a fundamental obsession for every misanthropic, virginal, independent comics reader on the planet. As a member of that self-loathing class, I was shocked and overjoyed when Clowes responded to my interview request for the second issue of our crummy, Xeroxed, punk fanzine, Meatnog. In June of 1995, just days after my 20th birthday, I took a five-hour drive in a borrowed station wagon to meet one of my few true heroes at a Berkeley donut shop. The interview was everything I’d hoped, as was the man himself: gracious, funny and brimming with hate. I left with a stomach full of crullers and a cassette full of gold.

Unfortunately, the second issue of Meatnog would never materialize. The co-editor fell on dark times and permanently vanished. My girlfriend testified in a double homicide court case, and we were driven out of state under death threats from a neo-Nazi skinhead gang. In our rushed exit, our belongings ended up scattered through various garages and attics, and the Clowes interview languished in a box for years. Transcribing it for this post, it’s incredible to realize just how much Clowes’ impenetrably negative worldview at the time represented our collective disdain for the disposability and stupidity of the ’90s. But rather than give up, his cultural disgust propelled him to do work that would ultimately establish him as one of the most important comics creators of the last two centuries. That antisocial drive has been an inspiration to countless readers, and is especially tangible here.

I apologize to you, and Mr. Clowes, for taking 20 years to get this thing out. Blame the skinheads.

ZACK CARLSON: I’m here at Dream Fluff Donut Shop in Berkeley, California, with Daniel Clowes.

DANIEL CLOWES: Hi.

CARLSON: Is Eightball going to be the forum for all of your work indefinitely?

CLOWES: Originally, I thought I’d come up with a new name after a while: something much better than Eightball. I figured, once I finished Like a Velvet Glove Cast in Iron, I’d change the whole format, change the title. But my publisher said that having a title that people remember is as good as gold, and you’re crazy to start over with a new one because then people have no idea what’s going on. They think you have your old series, and a new series, and it’s a confusing mess. So I don’t see any reason for doing that. Especially since I’ve never come up with a better title than Eightball anyway.

People still ask me when the next issue of Lloyd Llewellyn is going to come out.

CARLSON:Really?!

CLOWES: Yes! I explain that I stopped that to do Eightball. There’s no reason for me to do two comic books.

CARLSON: You said that you considered making changes after Velvet Glove. Do you feel like that’s your primary work — that it’s the most important thing that you’ve done so far?

CLOWES: My favorite is almost always what I’m working on now. Which is a problem. I spend five months working really hard on something that I’m completely involved in, and nobody sees it. I hardly even show it to my wife. And then when it’s finally done, I’m already tired of it. By the time it’s printed, I’m over it. I get letters from people responding to it and I don’t even care what they say, because I’m off working on something else. So if they like it, I say, “Oh. Well, that means you’re stupid. That’s old. It’s terrible stuff. But the next thing is going to be good!”

So my favorite thing is usually what I haven’t quite done yet. Like I’m starting something next week as soon as I’m done with what I’m working on.

CARLSON: Are you able to say what that is?

CLOWES: Sure. There’s no secrecy, because this thing is so rushed that it’s going to be out long before you could ever get your zine together. It’s just an animation for a music video, a Ramones version of a song that Tom Waits wrote, called “I Don’t Want to Grow Up.”

It’s sort of their swan song. This really is their final album. They’re retiring. They’re giving it up; they’re tired of it. So the record company is giving them a ton of money to do this video.

They’re not paying me a ton of money. To do the kind of animation that they want is really expensive, so they’re sinking their budget into this stuff. I get to design everything, and so far they’ve basically let me do whatever I want, which has been really fun. And Joey Ramone has all these stupid ideas that he wants, which I’ve had to turn down. He wants me to draw Rush Limbaugh and OJ Simpson into the video.

CARLSON: Wow. Dated.

CLOWES: Oh, yeah. Stuff that will be dated within a month. He thinks that’ll be funny, but I told them, politely, to leave comics and art to the professionals. It’s not like I’m going to try to play bass or anything.

CARLSON: How were you contacted to do that job?

CLOWES: Joey Ramone had never heard of me. When someone showed him my comics, they thought he might have seen my work somewhere, but he was completely unaware of it. But the producers of the video somehow got the idea to make a comic book the motif for the video, since it was about a kid who didn’t want to grow up. So someone said, “If you’re doing something with comics, get this guy.” It was just a lucky break for me.

None of them had heard of me until a couple weeks ago. I guess they gave the Ramones some copies of Eightball. They played a show in L.A. with Hole and some other young band, and this guy showed them my comics. The other bands were from Seattle, which is where my publisher is located, and the musicians from those bands all said, “Oh, yeah. We know this guy.” So that gave me some credibility with Joey … because Hole knew who I was.

CARLSON: Lucky you.

CLOWES: Yeah, lucky me.

CARLSON: Since you’re doing animation right now, has there ever been a point where you feel like you’ve done comics and you want to move on to something else?

CLOWES: I never get tired of what I’m doing. I’m always challenged. Comics are really difficult because you’re doing writing, storytelling, and you have to learn so many things that you’re just constantly improving.

I still have tons of stuff that I want to get done, but I get really frustrated with the business of comics, having to sell my stuff to superhero fans. There just aren’t stores for the type of comics that we do. There are alternative record stores that also sell comics, but they don’t really know how to actually sell them. It’s really irritating, and I’ve felt like quitting because of that. I hear stories of just … stupid comics selling millions of copies and that gets to me sometimes.

But the truth is that I’d probably keep doing it even if I only sold a hundred copies. I just wish I could reach the audience that I know is out there for this kind of thing. There has to be at least a hundred thousand people that would enjoy these types of comics, and they’re maybe getting to ten thousand.

CARLSON: But in the last couple years, your art has been able to reach more people, if not specifically Eightball. Even this music video —

CLOWES: That’s true. But somehow that doesn’t translate into people buying comics. People might see this Ramones video and like the artwork, but they’re never going to be in a comics store. Maybe if Eightball was sold in Waldenbooks at the mall, these people would run across it, but nobody but deviants go into comic-book stores. Certainly no girls will go in. People have to know about something and actually go in looking for it. It’s a real problem. It’s not something that’s gonna get picked up as an impulse buy. And the people who are going into comic shops mostly aren’t interested in Eightball or the other good comics that are being produced today. Sad, but true.

CARLSON: What are a few current titles that you like?

CLOWES: There’s a lot of great stuff. Virtually everything that the company Drawn & Quarterly publishes. He’s never picked a dud. And Fantagraphics is by and large the best in the business. Not to support my own publisher or anything, but those two companies have really cornered the market. There’s some good self-published work out there, but 99 percent of that stuff is crap: just endless imitations of each other. And the top five companies haven’t produced anything good … ever. Maybe once in 10 years, they’ll do something halfway decent.

CARLSON: Would you work with one of the larger companies if they offered you something you were comfortable with? Even if you weren’t fond of their general output?

CLOWES: Right now, no. The way that the situation currently is, I can envision a day where there might be just one company. Marvel has controlled the distribution so well that they’re almost becoming a monopoly. So if it got down to that, I don’t know what I would do. I hate to say that I’d work for a company like that, that’s just so horrible. But if it was the only way that I could get my work distributed, it’s possible: but in the present situation, definitely not. I’m really happy with Fantagraphics, and there’s a couple other small publishers that I wouldn’t mind working for. I hope they can stick it out through all the trouble that’s going on in the comics business right now.

CARLSON: Are you enjoying the animation enough to do more?

CLOWES: As of now, I haven’t even seen any of it yet. I only know what the colors look like, so we’ll have to see how it looks when it moves. It’s going to be really simple. I don’t have time to draw seven different arm movements each time a character moves, so they’re more or less just moving it like a paper doll. It may look really dopey. I don’t know. If it looks the way I envision it, it’ll be great. But frankly, I’ve never been a fan of animation. This is kind of the perfect thing because it’s only taken a week, so it hasn’t driven me nuts.

CARLSON: If you weren’t making a living at comics right now, what would you be doing? And what was the last thing you had to do?

CLOWES: Jeez, the last thing I did for an income was sponging off girlfriends like 10 years ago. That was how I lived when I first started. If I had no other opportunities in comics, I would be seriously fucked. I have no skills at all. I would have to take out a loan and go to school to learn how to type or something. I have no marketable skills whatsoever. I’m really bad with figures and numbers and things like that.

Right now, if comics just ended, I’d either have to try to make movies or do some kind of writing: a screenplay or something. I have friends who are being paid 40 or 50 thousand dollars a year to write screenplays that are never even going to be read by anybody. It’s just these contracts where they’re basically kept out of circulation, from working on projects with other studios. I’d love to get a deal like that, where you just get paid to do nothing. A friend of mine is a writer for The Simpsons, and asked for my help in writing a TV pilot that would never get produced. He wanted a bunch of ideas that were too over the top to ever actually get made, so I came up with all these things where the next-door neighbor is Hitler and stuff like that. All the money in the world is in Hollywood, so I guess that’s where I’d have to go. But I’m really happy where I am now, so I hope I don’t have to sink to that level.

CARLSON: Is that pilot script still around somewhere?

CLOWES: I assume it’s under lock and key somewhere. I don’t know. All these scripts are floating around somewhere in Hollywood.

CARLSON: You moved from Chicago to Berkeley. For what reason?

CLOWES: Well, I was married in Chicago, got divorced and met my present wife. She was going to school in Berkeley, so I moved here to be led around by her, basically. I really wanted to get out of Chicago, to avoid my ex-wife and for other reasons. But I really like it out here.

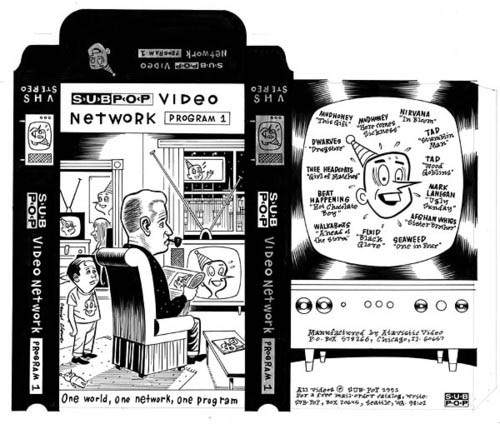

CARLSON: The first time I met you was at a record store here.

CLOWES: Yeah, I miss the old days when you could find great used records for like a quarter. So it’s really tough for me to spend 15 bucks on something I know I could have gotten five years ago for a quarter. But luckily, right now I’m on two mailing lists, from Rykodisc and Sub Pop. And since I listen to almost nothing that the two of them put out, I can trade in their releases for other records, which is almost like getting records for free. I don’t know, I’m always just looking for that one record I’ve never heard of before. Something new. It’s getting harder. I buy most of my records for the cover. It’s a real crapshoot. I have a lot of records that I’ve only listened to a few seconds of and never again.

CARLSON: But you kept them for whatever reason.

CLOWES: I kept them for the covers. And every once in a while, I’ll hit a great one. It’s worth it that one out of a hundred times.

CARLSON: Back to comics … you started off working for Cracked magazine, right?

CLOWES: Well, the earliest stuff I really did was at Cracked, and Lloyd Llewellyn started right after.

CARLSON: And what was the name your Cracked stuff was under?

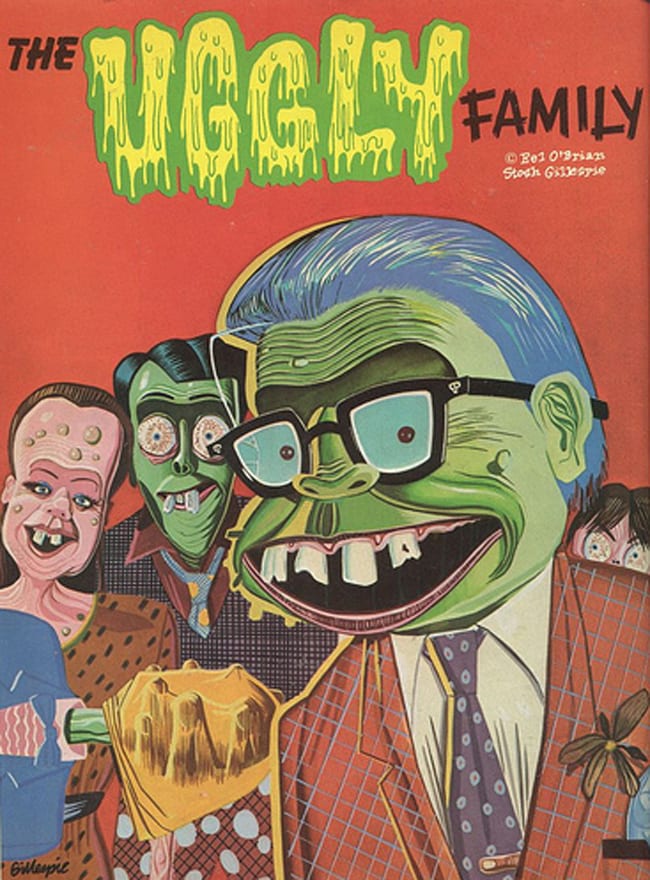

CLOWES: “Stosh Gillespie.” That was because I did a story under my real name for Cracked, and they’d just been bought by this new publisher. He wanted to assert himself and show that he was in charge. So he started going through this pile of submissions, and when he got to my stuff, he said, “This guy. Don’t use him. He’s no good.” And the next page he comes across is by Peter Bagge, and he says, “This guy’s no good. Don’t use him again.” And he comes across J.D. King and says the same thing. Then the next guy is someone that you’d never hear of again and he says, “He’s OK. Use him.”

So this guy basically got rid of three artists he had who’d go on to actually do something, just to show that he had power. So I resubmitted the exact same story, with my name changed to Stosh Gillespie. And the publisher said, “Now this guy, he’s OK.” He had no idea that it was the same artist: totally clueless. He could have had tons of early Peter Bagge stuff. He blew it.

CARLSON: So he still doesn’t know to this day what he had?

CLOWES: I remember the editor there was Mort Todd, and he said to the publisher, “This guy J.D. King is just about to become an important illustrator. In 20 years, people are gonna look back and say, ‘Look! His earliest work was in Cracked. Those guys were visionaries.’” And the publisher said, “Well, if he’s gonna be big in 20 years, tell him to come back then!” A real genius.

CARLSON: Are there any plans to repackage some of your earliest stuff, from back in that period?

CLOWES: You know, I’d be happy to. Just because, to me, it’s kind of funny. I had to work nonstop on that stuff. I’d have to do maybe five pages in two nights, and I’d just stay up and hack it out. It was hilarious.

But most of the artwork is “missing,” which means someone left it somewhere or threw it away. So I just have no copies of most of it, aside from the bad newsprint copies in the Cracked issues themselves, which you can’t really print from. So if someone could turn up the pages, we would gladly do it. Groth has said Fantagraphics would do it. But it’s missing. If anyone out there has it, let us know.

CARLSON: That’s where I first saw your stuff. I was really into Cracked. All the kids at school who liked Mad were probably the ones who beat me up.

CLOWES: Cracked is for real losers.

CARLSON: I was such a nerd that I even had to go for the underdog joke mag.

CLOWES: I liked Cracked for that reason. It’s funny, because a lot of kids your age are telling me that’s where they first saw my stuff. And to me, it’s unfathomable that they’d even recognize that it was the same artist.

CARLSON: It was because Lloyd Llewellyn’s best friend Ernie looks a little like Melbin from your Uggly Family strip.

CLOWES: Right.

CARLSON: I came across Lloyd Llewellyn #5 and thought, “Hey, this looks like that guy who draws for Cracked.”

CLOWES: How old are you? 21?

CARLSON: I just turned 20.

CLOWES: See, 20. That’s the perfect age where you would have been 12 or 13 when I was doing that stuff. Just recently, I’ve gotten maybe five letters from that same age range of people who say they first saw my stuff in Cracked. And I always think they’re kinda making fun of me, like, “I know you did stuff for that magazine!” like they’re trying to torment me. But they say they liked it.

People your age … when you were born, Cracked had already been in existence for like 15 years, so you can’t see the difference. When I was a kid, we knew that Mad was much superior to Cracked. But by the time you were a teenager, they were pretty much equal. Mad had gotten worse and Cracked may have gotten a little better, so there wasn’t a huge gap between the two.

CARLSON: And after Don Martin went to Cracked—

CLOWES: Yeah! It’s a toss-up. The last issue of Mad that I saw — Cracked might even be better. Though Mad has Drew Friedman now.

CARLSON: Really?

CLOWES: Hard to believe.

CARLSON: I was at Walmart and I saw a back-to-school set that Drew Friedman had drawn: some stationary and matching pencils.

CLOWES: Yeah. He’s getting these real jobs.

CARLSON: Are you ever approached by companies like that to do art?

CLOWES: No, and it’s weird because I’d love to get easy jobs like that. Like Peter Bagge got work for this other company that makes pencils for kids. They just let artists do whatever they want, so he got to design these pencils, design the packaging. He did these Grunge Pencils, with longhaired rock band guys. It was the funniest thing in the world, he got paid well, and it probably took him about an hour to do it. I said, “Give the guy my number! I’d love to do that.” But he never called. I don’t have enough of a schtick. You have to have a thing.

CARLSON: If someone who makes products for kids read an issue of Eightball …

CLOWES: They might be a little worried, yeah. But I mean, Hate isn’t the most wholesome comic in the world either, and they went for that. I’ve talked to art directors at these places who say they like my stuff. And then after that conversation, they really read it, and they’re not always so eager to praise me after that. “Well, I like some of it.”

CARLSON: Have you had any bizarre reactions to your work? An angry parent, or someone evaluating you mentally?

CLOWES: Yeah. I’ve had a few people who seem like they might have gone through really intensive therapy, and somehow my comics were really similar to dreams they’d had or something. There was one guy who was sort of obsessed with my comics and took them to his psychiatrist, and she forbid him to look at my comics again. He was on a strict regimen to not see what was in the next issue.

CARLSON: Kind of flattering, though.

CLOWES: It is. To think that I was able to disrupt some psycho’s brain patterns. But yeah, I’ve gotten letters from Christians. When I did that anti-Christian comic, which I felt was really pretty sympathetic, I got letters from hardcore Christians who didn’t agree with what I had to say.

CARLSON: Were they diplomatic about it?

CLOWES: Well, you know, Christians are never diplomatic. It was like they were trying to save me. It was: “You’re in big trouble, and I’m trying to help you.” In a way, if they really believe that, then they’re just trying to be nice. So it’s hard to say, “Fuck you, man.” And it’s hard to not take them seriously, since they’re so serious about it themselves. So I tried to be nice when I wrote back. Even though I thought they were idiots.

CARLSON: Is there anything that you’d say to someone who’s looking to make a living in independent comics?

CLOWES: I’d like to see people who are doing their own comics put a lot more work into it. I see people approaching minicomics and self-published comics the same way they’d approach starting a garage band. Like, “Anybody can do it! Anyone can pick up a guitar!” But comics and art just aren’t the same as music. You can’t expect the same visceral appeal that music has. You really can just pick up a guitar and make meaningful stuff, but you can’t just pick up a pen and do great comics the first time out. You have to work at it a lot. So I would encourage people to work at it and not expect instant gratification. I’d love to see people really devote themselves to comics, because that’s what we need.

CARLSON: Well, thanks for taking the time. And for showing me this great donut shop.

CLOWES: I love this place. It’s open from like five in the morning to … maybe three in the morning: with the same people working here. Gotta support it. I don’t know how they stay in business.