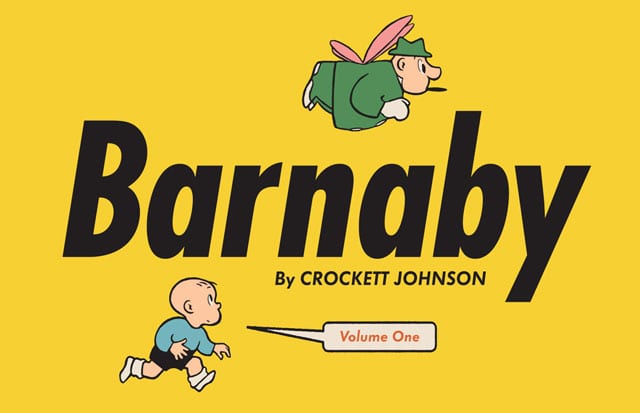

A boy named Barnaby wishes for a fairy godmother. Instead, he gets a fairy godfather who uses a cigar for a magic wand. Bumbling but endearing, Mr. O’Malley rarely gets his magic to work — even when he consults his Fairy Godfather’s Handy Pocket Guide. The true magic of Barnaby resides in its canny mix of fantasy and satire, amplified by the understated elegance of Crockett Johnson’s clean, spare art. Using typeset dialogue (Barnaby was the first daily comic strip to do so regularly) allowed Johnson to include — by his estimation — some 60% more words, giving O’Malley more room to develop a rhetorical style that, as one critic put it, combines the “style of a medicine-show huckster with that of Dickens’s Mr. Micawber.” In its combination of Johnson’s sly wit and O’Malley’s amiable windbaggery, a child’s feeling of wonder and an adult’s wariness, highly literate jokes and a keen eye for the ridiculous, Barnaby expanded our sense of what comics can do.

A boy named Barnaby wishes for a fairy godmother. Instead, he gets a fairy godfather who uses a cigar for a magic wand. Bumbling but endearing, Mr. O’Malley rarely gets his magic to work — even when he consults his Fairy Godfather’s Handy Pocket Guide. The true magic of Barnaby resides in its canny mix of fantasy and satire, amplified by the understated elegance of Crockett Johnson’s clean, spare art. Using typeset dialogue (Barnaby was the first daily comic strip to do so regularly) allowed Johnson to include — by his estimation — some 60% more words, giving O’Malley more room to develop a rhetorical style that, as one critic put it, combines the “style of a medicine-show huckster with that of Dickens’s Mr. Micawber.” In its combination of Johnson’s sly wit and O’Malley’s amiable windbaggery, a child’s feeling of wonder and an adult’s wariness, highly literate jokes and a keen eye for the ridiculous, Barnaby expanded our sense of what comics can do.

Though one of the classic comic strips, Barnaby was never a popular hit — at its height, it was syndicated in only 52 papers. By contrast, Chic Young’s Blondie was appearing in as many as 850 papers at that time. As Coulton Waugh noted in his landmark The Comics (1947), Barnaby’s audience may not “compare, numerically, with that of the top, mass-appeal strips. But it is a very discriminating audience, which includes a number of strip artists themselves, and so this strip stands a good chance of remaining to influence the course of American humor for many years to come.” He was right.

Barnaby’s fans have included Peanuts creator Charles Schulz, Family Circus creator Bil Keane, and graphic novelists Daniel Clowes, Art Spiegelman, and Chris Ware. It had many fans beyond the world of comics, too. Dorothy Parker compared Barnaby to Huckleberry Finn, and said: “I think, and I am trying to talk calmly, that Barnaby and his friends and oppressors are the most important additions to American arts and letters in Lord knows how many years. I know that they are the most important additions to my heart.”

It had a smaller following than other strips, but its fans were both more influential and more devoted. As Johnson wryly observed in late 1942, “If Dick Tracy were dropped from the News, 300,000 readers would say, ‘Oh dear!’ But if Barnaby went from [the newspaper] PM, his 300 readers would write indignant letters.” Though he didn’t say so, even reaching those 300 readers was an uphill struggle. If not for a chance meeting with an art editor, Crockett Johnson’s graphic masterpiece might never have been published at all.

In 1939, Crockett Johnson turned 33, fell in love, and began considering a career as a syndicated cartoonist. He’d spent most of his career as an art editor — in 1927, for Aviation magazine, and then, in 1929, for a half-dozen McGraw-Hill trade publications. In 1934, he began contributing cartoons to New Masses, becoming in 1936 its art editor, a job that paid only $20-$25 per week. He worked for the Communist weekly because he believed in its message, but, he thought, perhaps a daily comic strip would provide a better source of income? Maybe it was time for a change.

Johnson was then facing other big decisions. After a half-dozen years together, he and his wife Charlotte had decided to divorce. In the fall of 1939, at a party either in Greenwich Village or on Fire Island (sources differ), the soft-spoken, taciturn Johnson met the outgoing, adventurous Ruth Krauss. Recently divorced herself, she was a slender five-feet-four. He was nearly six feet tall, with the build of an ex-football player. Complimentary opposites, they felt an immediate attraction to one another. Within a year, she moved into his West Village apartment, he left New Masses, and invented a strip that would become a minor classic.

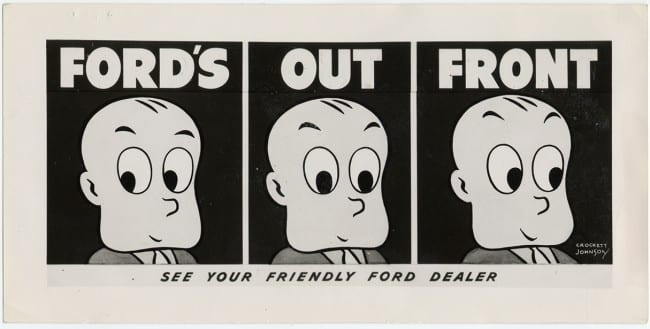

Popularly known as The Little Man with the Eyes, Johnson’s first comic strip was nearly wordless. Reminiscent of Otto Soglow’s The Little King in both its spare, clean line, and its gentle humor, The Little Man made its debut in Collier’s weekly in March 1940. Using only the caption and the movement of the central character’s eyes, the strip offered comic observations on life’s daily absurdities. During its nearly-3-year run, it became popular enough to inspire an advertising campaign for Ford later in the decade.

Popularly known as The Little Man with the Eyes, Johnson’s first comic strip was nearly wordless. Reminiscent of Otto Soglow’s The Little King in both its spare, clean line, and its gentle humor, The Little Man made its debut in Collier’s weekly in March 1940. Using only the caption and the movement of the central character’s eyes, the strip offered comic observations on life’s daily absurdities. During its nearly-3-year run, it became popular enough to inspire an advertising campaign for Ford later in the decade.

The Little Man was largely apolitical. Johnson, however, was very political. Seeking a strip with a wider range of expression than The Little Man, by late 1940 he had the idea of building a daily comic around a precocious 5-year-old boy living in a proper suburban home. He realized that he had always been thinking of the boy as “Barnaby,” and so that became the title character’s name. After drawing a few episodes, he realized that Barnaby wasn’t enough to sustain the strip. So, as he said, “I fumbled around, just like O’Malley, and O’Malley came in by himself.”

The Little Man was largely apolitical. Johnson, however, was very political. Seeking a strip with a wider range of expression than The Little Man, by late 1940 he had the idea of building a daily comic around a precocious 5-year-old boy living in a proper suburban home. He realized that he had always been thinking of the boy as “Barnaby,” and so that became the title character’s name. After drawing a few episodes, he realized that Barnaby wasn’t enough to sustain the strip. So, as he said, “I fumbled around, just like O’Malley, and O’Malley came in by himself.”

With the introduction of Barnaby’s cigar-champing con artist of a fairy godfather, Johnson’s strip found its source of narrative conflict, satire, and possibility. But Johnson couldn’t interest a syndicate in Barnaby. In any case, he was busy. When the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor drew America into World War II, he was not called to serve. Instead, in January of 1942, he co-founded the American Society of Magazine Cartoonists’ Committee on War Cartoons. The following month at the Arts Students League, the Committee’s Artists Against the Axis exhibition made its debut. Charles Addams, Peter Arno, Maurice Becker, William Gropper, Syd Hoff, Charles Martin, Garret Price, Gardner Rea, Ad Reinhardt, Carl Rose, Saul Steinberg, Arthur Szyk, Barney Tobey, and of course Crockett Johnson all contributed work. The show would go on to tour the country, raising money for the Allied war effort.

Also in early 1942, Johnson and Krauss moved to the country — Darien, Connecticut. Only an hour’s train ride from the bustle of Manhattan, Johnson worked on the Little Man. It might have remained his best-known creation but for a visit from his friend Charles Martin, who had recently become Art Editor of the Popular Front newspaper PM. When Martin saw a half-page color Sunday Barnaby strip, he liked it and asked if he could bring it back to the city. Johnson said sure. Back in New York, Martin showed the strip to King Features. They didn’t like it. He showed it to PM’s new Comics Editor Hannah Baker, and she loved it.

Also in early 1942, Johnson and Krauss moved to the country — Darien, Connecticut. Only an hour’s train ride from the bustle of Manhattan, Johnson worked on the Little Man. It might have remained his best-known creation but for a visit from his friend Charles Martin, who had recently become Art Editor of the Popular Front newspaper PM. When Martin saw a half-page color Sunday Barnaby strip, he liked it and asked if he could bring it back to the city. Johnson said sure. Back in New York, Martin showed the strip to King Features. They didn’t like it. He showed it to PM’s new Comics Editor Hannah Baker, and she loved it.

Thanks to her encouragement, on April 14th, 1942, PM’s readers got their first glimpse of Barnaby — he is walking, looking skyward, and calling “Mr. O’Malley!” This was the first of several ads announcing Barnaby’s debut the following week.

Thanks to her encouragement, on April 14th, 1942, PM’s readers got their first glimpse of Barnaby — he is walking, looking skyward, and calling “Mr. O’Malley!” This was the first of several ads announcing Barnaby’s debut the following week.

Though Johnson usually claimed that there was no one particular inspiration for Barnaby’s fairy godfather, he did admit that “O’Malley is at least a hundred different people. A lot of people think he’s W.C. Fields, but he isn’t. Still you couldn’t live in America and not put some of Fields into O’Malley. O’Malley is partly [New York] Mayor La Guardia and his cigar and eyes are occasionally borrowed from Jimmy Savo,” the diminutive vaudeville comic and singer. It’s equally likely that autobiographical inspiration for O’Malley came from Johnson’s father, David Leisk. He shared with Barnaby’s fairy godfather a creative mind, a taste for stories, a sense of possibility, and the fact that both men are foreigners. Born in the Shetland Islands, the elder David Leisk loved literature, wrote poetry, liked to sing, was a skilled carpenter, and had worked as a journalist before becoming a bookkeeper at New York’s Johnson Lumber Company — the source for his son’s middle name.

Crockett Johnson was born David Johnson Leisk in Manhattan in 1906, and grew up in Corona, Queens — which was then much more like the suburban neighborhood where Barnaby lives. Johnson’s childhood fondness for exploring the great outdoors may have led him to a comic strip about frontiersman Davy Crockett. He was not the only “Dave” in the neighborhood, but he could become the only “Crockett.” In the 1930s, he used this childhood nickname for the first half of his pen-name, “Crockett Johnson.” But he otherwise did not use the name as an adult. Friends knew him as “Dave Johnson.”

Though not given to talking about himself, Johnson, in admitting that Barnaby was based on no particular children, quietly acknowledged that the character comes from his own childhood. “I don’t get anything much from kids,” he told the Philadelphia Record’s Charles Fisher. “How can you? They are all different. And I don’t draw or write Barnaby for children. People who write for children usually write down to them. I don’t believe in that.” Told that children also like Barnaby, Johnson smiled and said, “I’m glad when I hear they do. You see . . . well, when it comes to knowing about children, it’s a terribly old thing to say, but everyone was once a child himself.”

Crockett Johnson also drew on his fascination with odd pieces of knowledge, the best example of which is Mr. O’Malley’s favorite expression, “Cushlamochree!” What does it mean? Johnson himself answered that question, responding to a letter from a Barnaby fan.

His etymology reads as if he were writing it while sitting next to the Compact Oxford English Dictionary, open to the entry for “acushla.” He was probably doing exactly that. Johnson enjoyed reference works, collecting peculiar facts — the very sort of information that O’Malley likes to cite, creatively mangling it in support of his latest scheme.

If O’Malley’s schemes resemble those ideas that seem compelling in the evening but not in the harsh light of day, that’s because Johnson was nocturnal, typically writing Barnaby between 11 p.m. and 5 a.m. Generally, he spent the first two nights writing the script, and the next two drawing the art. Next, PM’s type shop set Johnson’s dialogue in italicized Futura medium, and sent it back to Johnson. He cut out these thin strips of words and pasted them into each panel. He would either have to bring the strips into New York himself, or, if he was running late, rely on his neighbor Bob McNell to drop them off at PM’s offices on his way to his ad agency job. Sometimes, Johnson was running so late that he would bring them over to McNell at 6 a.m., the glue still drying.

By the fall of 1943, the strip was in PM, the Chicago Sun, Philadelphia Record, St. Louis Star-Times, Harrisburg Telegraph, St. Petersburg Times and Troy (N.Y.) Record. In terms of circulation, Barnaby was no Blondie or Dick Tracy, but it was already earning Johnson a $5000 annual salary — which, in today’s dollars, would be about $65,000. And it had prospects. As soon as he could find a sponsor, Johnson was planning on a Barnaby radio show. There was even talk, that spring, of creating a musical comedy based on Barnaby. That same spring, Johnson made his debut as a children’s-book illustrator with the publication of Constance J. Foster’s This Rich World: The Story of Money.

Amidst this busy schedule, Krauss was working on her first children’s book, A Good Man and His Good Wife, and was about to become a wife for the second time. After living together for over two years, she and Johnson formalized what most of their neighbors assumed they had already done. In June 1943, they got married.

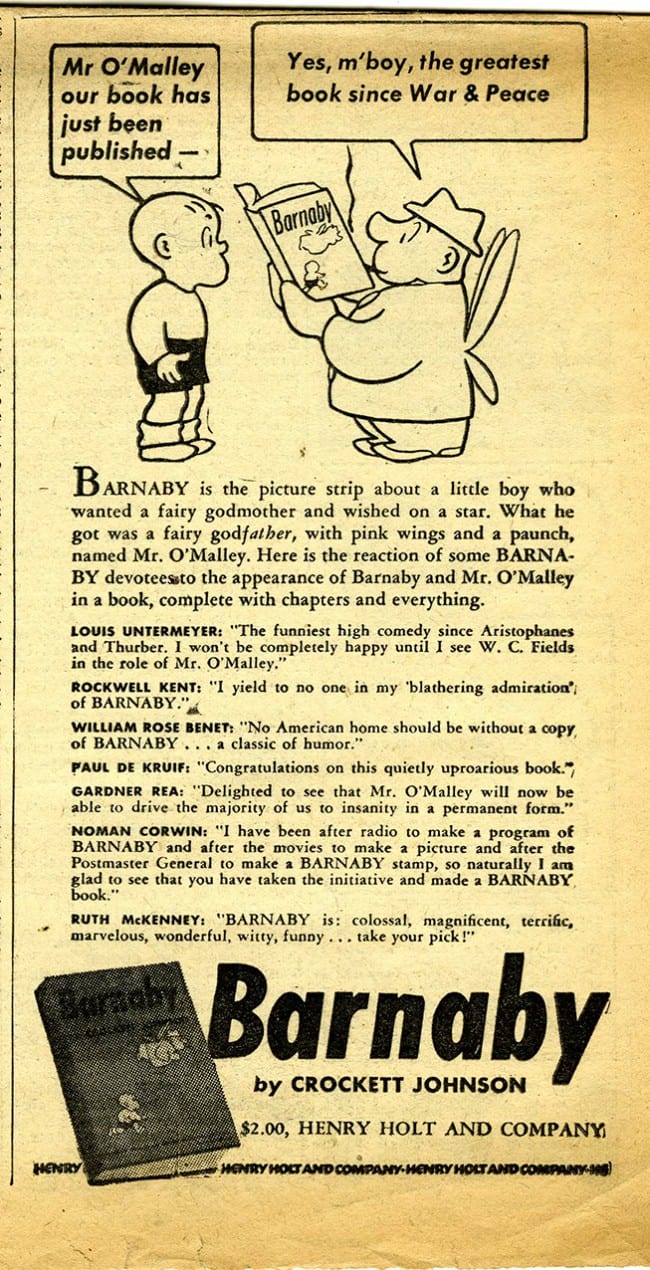

In October, Henry Holt published Johnson’s Barnaby. It sold its first printing of 10,000 copies in its first week, and would sell 40,000 before the end of the year. The reviews were ecstatic. Pulitzer Prize-winning poet William Rose Benèt called Barnaby “a classic of humor” and declared Mr. O’Malley “a character to live with the Mad Hatter, the White Rabbit, Ferdinand, and all great creatures of fantasy.” Ruth McKenney, whose My Sister Eileen had become an Oscar-nominated film earlier that year, delighted in “that evil intentioned, vain, pompous, wonderful little man with the wings.” As she put it, “I suppose Mr. O’Malley has fewer morals than any other character in literature which is, of course, what makes him so fascinating.” Dorothy Parker began her “Mash Note to Crockett Johnson” by confessing that she could not write a review because, despite her efforts, “it never comes out a book review. It is always a valentine for Mr. Johnson.” Lauding the book as “the best American creative writing of this year” and O’Malley as “the most brilliantly conceived character in many a year,” novelist and Book-of-the-Month Club publicity director Edwin Seaver nominated Barnaby for a Pulitzer.

At the age of 37, Crockett Johnson suddenly had fans. Life and Newsweek had both run features on Barnaby. Critics loved his book. However, adulation both pleased him and bemused him. It was great to be a success, but he also enjoyed not being the center of attention. And success seemed to bring more work, which used time he might otherwise have spent sleeping, reading, sailing, … or having a lamb sandwich. He had not only to turn out six Barnaby strips per week, but also to make each strip meet his standards. “I never feel that I can let down,” he told a journalist in November 1943. “If I did, the stuff wouldn’t get to be just mediocre; it would be terrible.” While Johnson felt that “There’s nothing worse than the obligation to be funny,” he also considered Barnaby “a pretty good racket.” Racket? Perhaps Mr. O’Malley’s great unacknowledged source is the life of Crockett Johnson himself — with the key difference being that Johnson’s “racket” was actually successful. Cushlamochree!