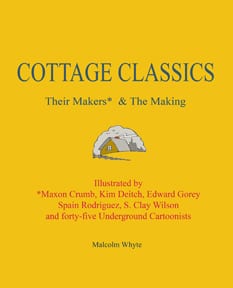

In 1997, at an age when most men’s life planning turns toward Social Security, Malcolm Whyte launched a new career. He had formerly published books and he wanted to again. But what books and on what scale? What new challenges would gratify and what old headaches could he avoid? What, if not massively profitable, would not cost his neck? These answers and stories that surround them are provided in Whyte’s slim (110 page, including illustrations and photographs), elegant, lovingly constructed Cottage Classics: Their Makers & The Making (Word Play. 2014).

In 1997, at an age when most men’s life planning turns toward Social Security, Malcolm Whyte launched a new career. He had formerly published books and he wanted to again. But what books and on what scale? What new challenges would gratify and what old headaches could he avoid? What, if not massively profitable, would not cost his neck? These answers and stories that surround them are provided in Whyte’s slim (110 page, including illustrations and photographs), elegant, lovingly constructed Cottage Classics: Their Makers & The Making (Word Play. 2014).

I

Whyte was born in 1933 in Milwaukee. He graduated Cornell in 1955, a literature major, and, facing the draft, calculated that three years in the navy, with its “better food and fewer bullets” would be preferable to two in the army and signed up. While stationed aboard the Oriskany, an aircraft carrier out of San Francisco, he and a shipmate, Brady Harris, with whom he shared an interest in the arts and satiric humor, camouflaged in chinos and turtlenecks, would venture weekends into North Beach beatnik haunts, like the Co-Existence Bagel Shop and Anxious Ass, a bar that featured hip fare, like blue cheese on burgers.

Still in the service but seeking simpatico employment for when they weren’t and drawn to the Bay Area’s eccentricities and charm, Whyte and Harris launched Troubador Press. Its main thrust sought to carve a niche in the high-brow end of the greeting card market by imprinting for-the-occasion quotes from Shakespeare on theirs. To tide themselves over, they bid on commercial printing jobs, winning from City Lights Books the contracts, among others, to print Alan Watts’s Beat Zen, Square Zen & Zen, Norman Mailer’s The White Negro, and the first expletives-restored edition of Alan Ginsberg’s Howl.

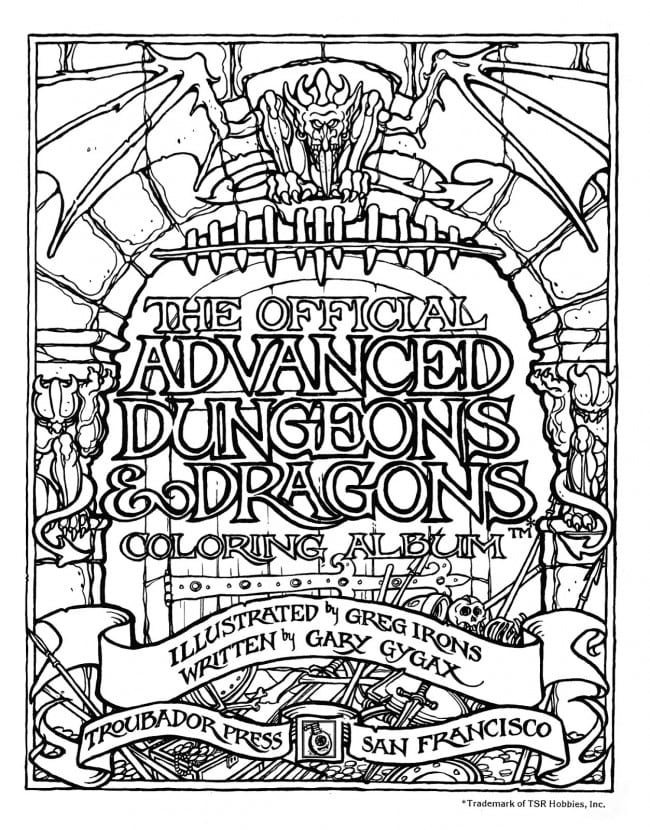

These successes though failed to provide Harris enough on shore to sustain him. Like Ishmael, he found himself drawn again to “the watery part of the world” and re-Navy-upped in 1961 – eventually retiring a full captain. Whyte carried on ashore, and, by the mid-sixties, had expanded Troubador to include publishing its own books. First came The Fat Cat Coloring and Limerick Book, then The Love Bug Coloring and Limerick Book, and, plucking topics from the froth of popular culture, books on whales dinosaurs, Native Americans, monsters, robots, Dungeons and Dragons, and the occult, the text often by Whyte, and the illustrations by artists like Larry Evans, Greg Irons and Larry Todd. By 1982, when Whyte sold Troubador, it had its own printing plant, warehouse, fifteen employees, and 135 titles to its credit. He remained Editorial Director, producing four books a year until 1996.

Meanwhile, Whyte had become an passionate collector of comic art. (This had begun innocently enough when, in 1964, he had written Charles Schulz a fan letter and received a signed Peanuts strip by return mail.) One evening, after a few drinks, Whyte followed his passion to a beyond-natural conclusion by outlining on a cocktail napkin plans for a museum, where collectors could display their acquisitions and honor the medium they favored. In 1984, with several similarly inclined others, he founded the Cartoon Art Museum of San Francisco and went on to serve eleven-years as chairman of its board of trustees. But by the time he left Troubador, the museum was flourishing and his involvement had declined.

Meanwhile, Whyte had become an passionate collector of comic art. (This had begun innocently enough when, in 1964, he had written Charles Schulz a fan letter and received a signed Peanuts strip by return mail.) One evening, after a few drinks, Whyte followed his passion to a beyond-natural conclusion by outlining on a cocktail napkin plans for a museum, where collectors could display their acquisitions and honor the medium they favored. In 1984, with several similarly inclined others, he founded the Cartoon Art Museum of San Francisco and went on to serve eleven-years as chairman of its board of trustees. But by the time he left Troubador, the museum was flourishing and his involvement had declined.

II

As Whyte describes it, his return to publishing was both practical and idealistic. It would be hard-headed in its business choices and warm-hearted in its artistic aspirations. He would do one book each year in an assortment of limited editions, each less numerous, more expensive, and more lavishly accoutred than the former, none of which would be reprinted. He would sell that book out and, the next year, do another. His books would be tied to artists he admired, with existing fan bases to whom the books would be offered, and from whom payment could be collected, before printing occurred. In this way, Cottage Classics, as Whyte would call his line, would require little marketing and scant advertising. Tie-ins with a few specialty distributors would suffice. He wouldn’t even have to give away review copies. His company would have no unpaid accounts to collect. It would have no inventory and no need of a warehouse or warehousemen. It would not need clerical staff or sales reps. It would have, in fact, no employees but him. As for the artists and the books that would make this vision work, Whyte was counting on a hopefully irresistible union between a body of much loved, nearly sanctified-into-pablum literature already within the public domain and the practitioners of an oft-reviled and under-valued corner of the graphic arts

Whyte had been an admirer of underground comix since the afternoon he had walked into Gary Arlington’s tiny store in San Francisco’s Mission District and been introduced to a tall, skinny fellow named Bob Crumb, who sold him a handful of first edition “ZAP” Number Ones for a quarter apiece. Whyte, as a married man with three children, who had been into, he recalls, “drinking martinis and not eating dope” had missed out on the early days of rock poster collecting, immediately recognized he was being invited into the ground floor of the latest exciting development in the graphic arts. He would stop by Arlington’s once-a-week, buy comix, meet artists, and acquire work from them. “They were interesting guys,” he says, “doing wonderful work, and I was in awe. I’d just go ga-ga.”

They were also artists whose choice of content had limited their audience and restricted their possibilities. By the mid-nineties, most of them worked in relative obscurity. Now, he hoped to bring them at least some of the attention and rewards they deserved.

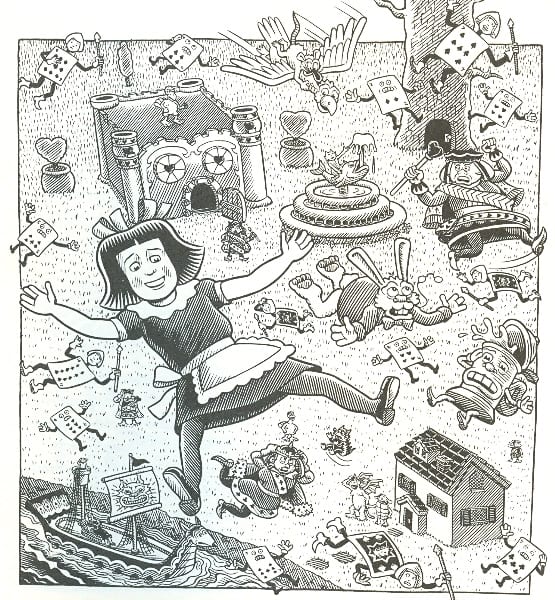

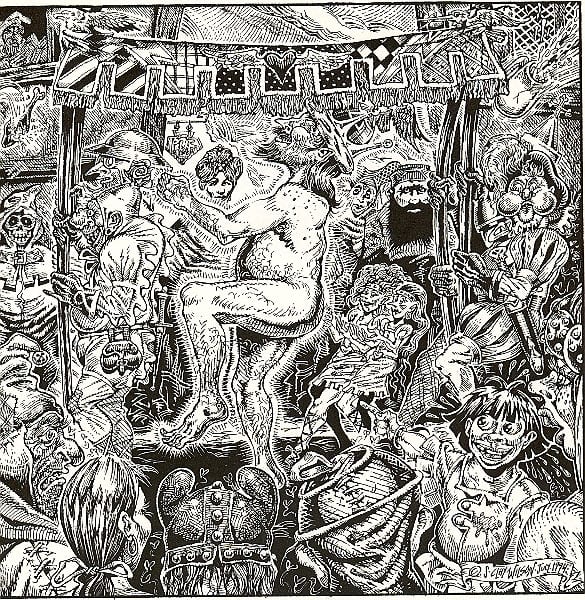

The result of Whyte’s vision were seven books, ranging in length from seventy-six to 190 pages. There were collections of stories by Hans Christian Andersen and The Brothers Grimm, spot- illustrated by the incorrigible, serially offenive S. Clay Wilson. (Wilson did not quite abide by Whyte’s “no-sliced-and-diced body parts and no genitalia” admonition, and Whyte tells the curious where to spot the deviations); an Edgar Allen Poe collection, lit-up by an artist who considered himself Poe’s equal as a genius and certainly bested him as a societal outsider, Maxon Crumb; tales of that redoubtable Victorian stalwart, Sherlock Holmes, re-imagined by the ex-biker, committed socialist Spain Rodriguez; and an Alice’s Adventures under Ground, in which the playfully past-obsessed Kim Deitch had a go at besting Lewis Carroll’s and Sir John Tenniel’s interpretations. In addition, Whyte published a complete-as-could-be-managed compendium of the work of Edward Gorey, covering everything from his work for books to magazines to record albums to t-shirts and bean bag dolls, with new illustrations by that Old School, New England eccentric himself; and an album of photographic portraits, by Clay Geerdes, of fifty underground cartoonists, with brief biographies of each, written by Whyte. The photos had never before been published in one place. Nor had they ever been published in such size and with such clarity. The result was a stunning evocation of a past era, attitude and air that now seemed almost otherworldly.

The result of Whyte’s vision were seven books, ranging in length from seventy-six to 190 pages. There were collections of stories by Hans Christian Andersen and The Brothers Grimm, spot- illustrated by the incorrigible, serially offenive S. Clay Wilson. (Wilson did not quite abide by Whyte’s “no-sliced-and-diced body parts and no genitalia” admonition, and Whyte tells the curious where to spot the deviations); an Edgar Allen Poe collection, lit-up by an artist who considered himself Poe’s equal as a genius and certainly bested him as a societal outsider, Maxon Crumb; tales of that redoubtable Victorian stalwart, Sherlock Holmes, re-imagined by the ex-biker, committed socialist Spain Rodriguez; and an Alice’s Adventures under Ground, in which the playfully past-obsessed Kim Deitch had a go at besting Lewis Carroll’s and Sir John Tenniel’s interpretations. In addition, Whyte published a complete-as-could-be-managed compendium of the work of Edward Gorey, covering everything from his work for books to magazines to record albums to t-shirts and bean bag dolls, with new illustrations by that Old School, New England eccentric himself; and an album of photographic portraits, by Clay Geerdes, of fifty underground cartoonists, with brief biographies of each, written by Whyte. The photos had never before been published in one place. Nor had they ever been published in such size and with such clarity. The result was a stunning evocation of a past era, attitude and air that now seemed almost otherworldly.

“Cottage Classics” details how Whyte, to usher these volumes into being, acted as everything from publisher to editor to art director to mail boy. He selected texts for his artists to illustrate and set deadlines for them to meet. He designed jackets, laid out pages, determined book dimensions and typography styles. He negotiated contracts and determined what constituted “fair use.” He selected among competing printers and typesetters. He determined the size of each printing, soft and hard cover alike, the limited signed and numbered editions, the more limited, A-to-Z lettered, and the most limited, Roman enumerated I-to-XII. He decided which editions to slipcase, when to use gold ink, and when fabric covers. He chose how to make the pricey editions special and the even pricier ones more special still. He was the one who bought the stamps and mailing labels. He issued the checks. It was, Whyte concludes, “great fun.”

Much of this fun, for Whyte – and for his reader – lay in his interactions with his artists, who were, as he graciously puts it, “exceptionally independent souls.” He captures the unusual personality of each, recognizing how their quirks contributed to the power of their artistry, while giving voice to some of the difficulties they presented for someone set on realizing the commercial ends they ostensibly jointly pursued. Here is Wilson, in mid-negotiation, suddenly suspicious, calling in his attorney – 3000 miles away. Here is Deitch claiming his work schedule makes his participation impossible – unless his girl friend can be attached as his collaborator. And here is Crumb, the flinty asceticism of his lifestyle having ruled out access to a phone, requiring that all contact come via the mail, or Whyte’s visiting his one-room abode on San Francisco’s Skiddiest Row. (Whyte makes clear, though, that, once committed, each artist displayed the same professional commitment to their various projects.)

Whyte writes clear, clean prose, choosing each word carefully, aware of the weight it carries and the flavor it leaves behind. He is adept at explaining what makes each artist’s work special. Translating a visual experience into language is a tricky job and Whyte does a fine job. Here he is on Spain’s “miraculous job of picking the most electrifying scene in each story and reinforcing its impact with highly effective brush work.” Here he notes how Gorey’s “strong line, masterful crosshatching and solid composition command the page.” And here he salutes Wilson for his “strong, sure style, beautifully executed with facile pen and brush” and “(h)is heavy black areas (that) play against a meticulously detailed line that stirs intense emotions in the viewer.”

Whyte is also respectful of the artists’ privacy. There is little for those seeking gossip or scandal in Cottage Classics, though one can learn which female cartoonist Wilson had in mind when he drew “The Girl Who Trod On Bread” – and that his model for the title character in “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” dressed and undressed, was himself.

Writing about Geerdes’s photographs, Whyte praises him for putting faces on a school of “transformative artists of originality, irreverant wit and gritty determination.” His own book fires a equal salvo of salute. It is a delight for any fan of the unusual and unimaginative in art. It is valuable reading, as well, for anyone interested in the how-to’s of one-man publishing – or, for that matter, for anyone who is, in any fashion, at bone level a book person.

In fact, it may be here that Cottage Classics's greatest contribution lies. In an era of “The Book Is Dead” echos,” Whyte concludes, “As old publishing avenues close..., new ones open. There are still unique books to produce that will find their way to expectant audiences...” They just need to be narrowly focused and excitingly constructed – and they need publishers brave (and foolish) enough to be motivated by love, not money.

Cottage Classics is available from www.word-play.com.