At SPX 2013, I was happy to run into Matt Emery, who handed me a pile of comics that he had published. His Pikitia Press is located in Melbourne, but Emery is a New Zealand native and unsurprisingly publishes the work of a number of Kiwis as well as Aussies. The alt-comics scene there has long been small but feisty, but it seems to have grown dramatically in the past five to ten years. Here's a look at Pikitia's offerings.

Love Stories, by Mat Tait. Originally self-published in 2008, this collection of stories by New Zealander Tait is visually striking, dominated by his bold use of black and a thick, almost rubbery line. He doesn't sacrifice storytelling fluidity for these striking images; still, each panel can be viewed as a single, powerful moment as well as part of a greater whole. "Inland Sea" is a silent story about twins birthed on an island that segues into the disappearance and presumed death of their parents while trying to get food. It's the first segment of what appears to be a longer story, but it points to Tait's art at his best. The island gives and the island takes away, a dual contradictory feeling of gratitude and constant dread.

Love Stories, by Mat Tait. Originally self-published in 2008, this collection of stories by New Zealander Tait is visually striking, dominated by his bold use of black and a thick, almost rubbery line. He doesn't sacrifice storytelling fluidity for these striking images; still, each panel can be viewed as a single, powerful moment as well as part of a greater whole. "Inland Sea" is a silent story about twins birthed on an island that segues into the disappearance and presumed death of their parents while trying to get food. It's the first segment of what appears to be a longer story, but it points to Tait's art at his best. The island gives and the island takes away, a dual contradictory feeling of gratitude and constant dread.

"The Story of Rangi And Papa" is a funny take on the Maori creation myth, and it hits on the simultaneous gratitude and resentment children have toward their parents. Here, earth is created with a huge tree to separate the sky god and earth goddess, because "being trapped between your parents' eternal fuck would be unbearable." Tait is similarly cheeky in crisply retelling the story of a famous sheep dog who got split in half and put back together upside down. Here, the level of detail in illustrating the whorls on wood and cross-hatching deep shadow add to the myth's potency.

Tait has a sense of humor that ranges from dark to absurd. "Great Historical Disasters" is a bit of both as it recalls the "Bibles For Guns" initiative that was swiftly followed by the "Guns For Bibles" initiative. "The Admission of the Antarctic Empire to the UN" is more on the silly side, as we see a Jack Frost lookalike freezing the Secretary General at his podium. My favorite story in this excellent collection is "Shortcuts To Enlightenment", which proposes a series of ritualistic additions and ceremonies for one's house that culminate in enlightenment right before death. It's very reminiscent of Zak Sally, in the line quality, and because of the urgent and sardonic narrator and the ever-present sense that we are all doomed. Tait seems comfortable straddling the line between acknowledging mortality and celebrating our short lives.

Pay Through The Soul #2, by S.Emery and M.Emery. Emery and his brother specialize in gag work that looks like James Kochalka's but is much meaner. There's a gag about trees being casually racist wherein every one of the stereotypes comes true in a way that makes them suffer more and more. There's a gag about a snowman who urges a young boy to give him genitalia, only to get him in trouble with his father, all thanks to a wicked little sister with snow-proof walkie-talkies. There are the continuing adventures of Bitch Slap Bird, which is exactly what it sounds like, except that people inexplicably call on BSB for help—and often get sent back in time. Another strip about husbands and wives involves one husband taunting the other that his wife would leave him for the machines when they finally take over, and that's just what happens. That one is a clever subversion of typical comedy tropes, as are many of these strips. In that regard, the best American point of comparison might be someone like Sam Henderson. The Emerys are nowhere near as meta as Henderson can get, but it's clear that their main interest is tinkering with the machinery and structure of comedy in order to make it run in a different way, with cruelty and betrayal constant presences as comedic fuel.

Dreamboat Dreamboat, by Toby Morris. This is an earnest, attractive slice-of-life story done in a sort of tribute to Harry Lucey's Archie art. Morris wanted to do a story about the birth of rock 'n roll in New Zealand in the 1950s but didn't want to idealize that earlier era, one that was rampant with more overt sexism and racism. In this story, the James Dean-like rebel who comes into town and inspires a crush from a local girl turns out to be a thuggish rapist who forces himself on the girl's best friend. This occurs after the girls have achieved their dream of winning a local music contest and get their single recorded. The single, naturally, was inspired by the sleazeball. It's all a bit too melodramatic, on-the-nose and easily resolved in the end to have much impact. However, the way it plays on the excitement and potential of rock music arriving from distant shores is quite charming, as the band's formation, giddy excitement and later anxiety is portrayed in convincing detail. This was an early effort by Morris and it reads like a young artist's nascent and well-meaning attempt at social relevance that doesn't quite stick the landing.

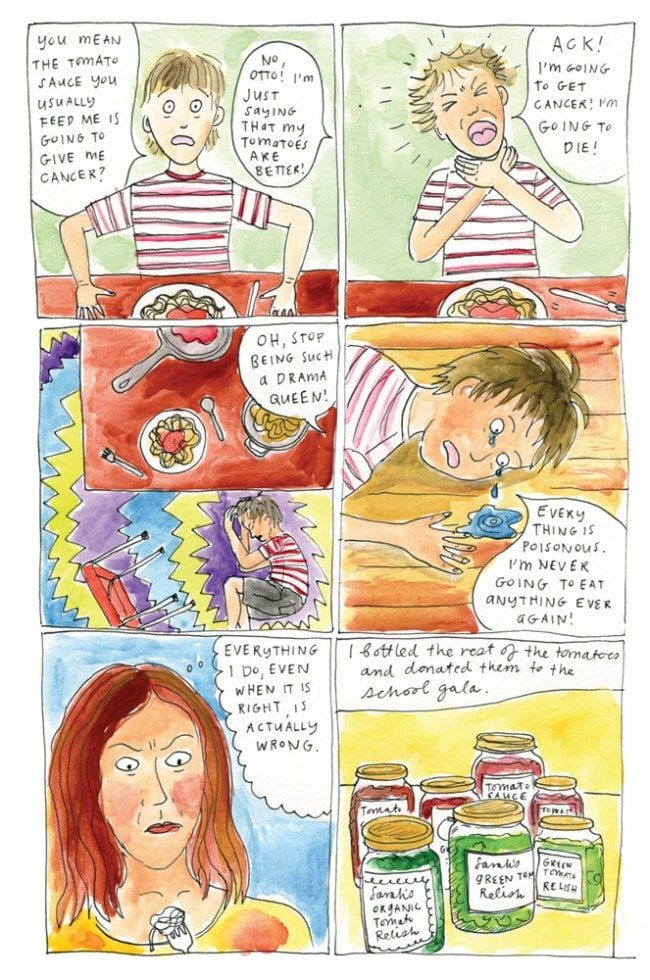

Let Me Be Frank #1, by Sarah Laing. These are excellent autobio strips about motherhood similar to those Keiler Roberts makes. Like Roberts, Laing is hilarious, self-deprecating, and self-revealing. Her affection for her children is obvious and omnipresent, but she doesn't sugarcoat her own thoughts, hopes, resentments, and desires. Her line is sketchy and slightly crude, but it's expressive and more than gets the job done in detailing funny and frantic anecdotes from her daily life. Comics about motherhood are starting to emerge in a number of different places, and the honesty in these pieces and the dedication they show to shattering myths and media idealizations is powerful, even as these women find themselves being pressured by these outside forces.

Like many mothers, she has an idealistic streak that proves to be her constant undoing. She grows her own tomatoes but has to cut out bugs and fungus from it, horrifying her son. Like Roberts, she delves into mental illness, talking about the anxiety problems her son faces, her own anxiety and then does a gag where her family is stacked on a couch and they get a "family discount for psychotherapy." Naturally, every generation says, "I blame it on my mother."

There's an epic story about walking to a local cafe with her three children, including a girl who is not yet potty-trained, that goes as disastrously as one might expect. When asked why she thought this excursion was a good idea, she says, "I don't know. I suppose I wanted a coffee." She talks about the nightmare of trying to keep a clean house with three kids; when her mom visits her, she reacts with horror--not at the state of the house, but flashing back to her own days as a daughter, telling her mother, "Don't hit the bottle!" There's another amazing story about her daughter throwing a fit in a grocery store, Laing trying to ignore it and then having to clean up when her daughter starts vomiting. As she takes in the disapproving stares of others, she thinks, "At least I can write a comic about it... Oh god, I really am a terrible mother!" Each of these stories is vivid, funny, and human. Laing really knows how to put an anecdote together and create a fluid narrative out of very little material. When she uses color, her stories pop even more, as their expressive quality becomes more prominent.

Deep Park, by David C. Mahler. This was my favorite of all the Pikitia releases; Mahler's darkly satirical and absurdist sense of humor is not unlike that of Matthew Thurber. This 54-page novella is a Carver-esque look at the lives of different people as they intersect during a day at the titular theme park. The book starts as a pointed critique of corporate escapist entertainment. The ways in which Mahler explores corporate entities' lack of regard for real human life get truly strange. For example, one of the many odd-looking characters goes on a Random Wilder-style soliloquy about the park before realizing that a particular seat on a roller coaster induces mind-boggling orgasms. He forms a cult around riding in this seat that is opposed by another secret cult of people who had previously discovered it and abandoned their former lives as a result.

Other threads involve the water in the water slide causing mind-destroying hallucinations for some of those who ride it, including a gay teen who breaks up with his boyfriend after being confronted by hallucination-induced agents of conscience warning about jealousy. Two punk thieves steal his backpack, get chased after taunting a guy about smoking, and heckle a concert by a band playing to a nearly-empty stadium. A kid comes to the park in a wheelchair after nearly being killed by the water slide, because he was given lifetime free admission in lieu of actual damages. The lawyers and managers of the park meet in a secret labyrinth to discuss how they'll avoid any other form of reparations, while being listened in on by a bird with the soul of a man that was torn out by a Sure Shot-style ride. The creator of the park looks for ways to destroy it. We come into each of these stories in media res, but Mahler quickly brings the reader up to speed and finds ways to connect the characters to each other.

These and other interlocking stories are hilarious, weird, and disturbing. Despite their seemingly random placement in the book, they slowly coalesce into the book's overall plot regarding the fate of the park, a fate that's doomed by the sort of spoiled, annoying brat that tends to be catered to in such settings. Mahler's visual trademarks are characters with bulging eyes and bloated bodies, a thin line weight and occasionally visceral images that prove shocking juxtaposed against the general cuteness of his overall line. It's a wonderfully bewildering book that rewards multiple readings, thanks to the complexity of its structure and the sheer strangeness of events on a page-to-page basis. The ending is hilariously nihilistic in much the same way Thurber's comics are: innocents suffer because this is what always happens in a careless, sprawling system that rewards greed and ignores exploitation.

Dailies #3, edited by Michael Fikaris and Tim Danko. This collection is not a Pikitia publication, but it serves as a great, quick summary of the scene as a whole. Printed on cheap magazine paper, Dailies has a wonderful pulpy quality that flatters some of the weirder and scratchier works in particular. The Aussie cartoonists included Kieran Mangan's funny, 4x8-panel grid story about two anthropomorphic houses with different fates; Leigh Rigozzi's page of unusual titles, fonts, and fake advertisements; Sam Wallman's hilarious "Faggot Perks for Perky Faggots"; Michael Fikaris' odd strip that falls somewhere between Noah Van Sciver and Ben Jones; and a funny and sad Simon Hanselmann about his Megg character trying to find marijuana. There's no uniform style or influence at work here, and the visual approaches range from naturalistic to cartoony.

There's also an extensive New Zealand section. Brent Willis contributes a misanthropic but intellectually curious strip about riding on public buses. Clayton Noone and Stefan Neville's story combines dense drawing techniques, big splash pages, and unusual typography. Chris Cudby works small but detailed in his story about an opportunistic superhero, while G-Frenzy's story about Kiwi relatives buying a pub while on duty during World War II in France is hilarious and Gary Panter-inspired in terms of its ragged line. Sophie Watson's story about a sort of zombie HR test is hilarious, while Indira Neville's drawings of children with tails scans like some strange descendant of Don Martin. There are a couple of dozen other cartoonists in here as well, some contributing illustrations and weird marks on paper and others doing somewhat more conventional storytelling. This is probably the most consistently intense distillation of the true underground/alternative scene scene I've seen from Australia and New Zealand, and while not every entry is great, they're all worthy of attention.