Later, my brother Drew would bring me down to earth: first, by reminding me that Superman was merely an actor; and then, throwing in for good measure that our mother called the actor who played Superman “a fag” (Drew, who considered himself the voice of reason, had burst my bubble before when I was around four, convincing me that our middle-aged, heavyset housekeeper, Mrs. Sullivan, wasn’t Mary Poppins, or age 19, for that matter; I would begrudgingly concede that she was 21). Neither Drew nor I knew what a “fag” meant, but I had associated it somehow with my mother’s friend, the renowned Broadway casting director and auditioning coach Michael Shurtleff, who once greeted us at the front door of his Greenwich Village flat looking like a white Aunt Jemima, dressed in a bandana and gingham cooking apron, holding a tray of warm muffins with colorful oven mitts. Drew and I looked at each other and started to snicker, ignoring our mother’s glare of disapproval. Besides being a mild-mannered reporter, did the Kansas-raised Man of Steel also lead a secret life wearing bandanas and gingham aprons while baking muffins in a Greenwich Village apartment?

Later, my brother Drew would bring me down to earth: first, by reminding me that Superman was merely an actor; and then, throwing in for good measure that our mother called the actor who played Superman “a fag” (Drew, who considered himself the voice of reason, had burst my bubble before when I was around four, convincing me that our middle-aged, heavyset housekeeper, Mrs. Sullivan, wasn’t Mary Poppins, or age 19, for that matter; I would begrudgingly concede that she was 21). Neither Drew nor I knew what a “fag” meant, but I had associated it somehow with my mother’s friend, the renowned Broadway casting director and auditioning coach Michael Shurtleff, who once greeted us at the front door of his Greenwich Village flat looking like a white Aunt Jemima, dressed in a bandana and gingham cooking apron, holding a tray of warm muffins with colorful oven mitts. Drew and I looked at each other and started to snicker, ignoring our mother’s glare of disapproval. Besides being a mild-mannered reporter, did the Kansas-raised Man of Steel also lead a secret life wearing bandanas and gingham aprons while baking muffins in a Greenwich Village apartment?Before I was even aware of comic books, like a lot of preschool-age boys I had already developed a fondness for superheroes, and perhaps the first superhero who fired my imagination was Gigantor, the space-age robot.  Developed by the same Japanese creative anime team that introduced Astro Boy, and later Kimba, the White Lion and Speed Racer, Gigantor was a huge flying robot with a jetpack attached to his back. A doe-eyed little boy named Jimmy, always dressed impeccably in a tweed suit and tie, controlled Gigantor with a joystick. Gigantor had a distinct pointy nose and narrow-set eyes that registered little emotion; whoever operated the joystick controlled Gigantor, and thus, the fate of the world. I must have been only three or four when I would watch mesmerized, probably bouncing up and down on the edge of my seat, while viewing black and white episodes of Gigantor on afternoon television. I think I was hooked from the infectious conga-tinged opening theme song which served as a clarion call to all viewing children—“Gigantor! Gigantor! Gigannnnnn-annnntor!” (Years later, it was fun to see my son’s similar reaction while watching the opening scenes of the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, which was reminiscent of Gigantor, only on steroids.) During recess at North Shore Day School in Glen Cove, Long Island, I would lead a parade of preschoolers as we marched across the playgrounds with outstretched arms as I sang the Gigantor theme song: “Bigger than big, taller than tall. Quicker than quick, stronger than strong. Ready to fight for right, against wrong. Gigantor! Gigantor! Gigannnnnn-annnntor!”

Developed by the same Japanese creative anime team that introduced Astro Boy, and later Kimba, the White Lion and Speed Racer, Gigantor was a huge flying robot with a jetpack attached to his back. A doe-eyed little boy named Jimmy, always dressed impeccably in a tweed suit and tie, controlled Gigantor with a joystick. Gigantor had a distinct pointy nose and narrow-set eyes that registered little emotion; whoever operated the joystick controlled Gigantor, and thus, the fate of the world. I must have been only three or four when I would watch mesmerized, probably bouncing up and down on the edge of my seat, while viewing black and white episodes of Gigantor on afternoon television. I think I was hooked from the infectious conga-tinged opening theme song which served as a clarion call to all viewing children—“Gigantor! Gigantor! Gigannnnnn-annnntor!” (Years later, it was fun to see my son’s similar reaction while watching the opening scenes of the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers, which was reminiscent of Gigantor, only on steroids.) During recess at North Shore Day School in Glen Cove, Long Island, I would lead a parade of preschoolers as we marched across the playgrounds with outstretched arms as I sang the Gigantor theme song: “Bigger than big, taller than tall. Quicker than quick, stronger than strong. Ready to fight for right, against wrong. Gigantor! Gigantor! Gigannnnnn-annnntor!”

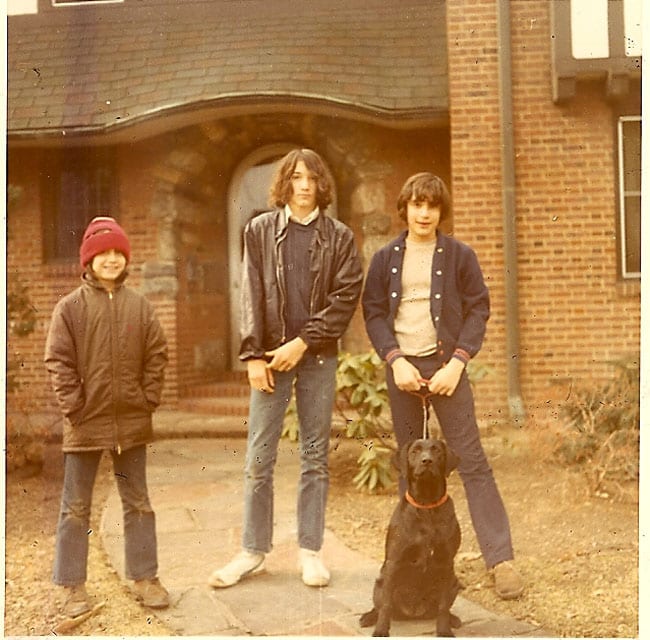

My comic book fever heated up around 1968. That was when we began a sort of weekend family ritual. My brothers and I would pile inside our father’s midnight-blue Cadillac Eldorado (which he regrettably had to return after my maternal grandfather, Papa, threw up in the back seat next to me one night after a particularly spirited dinner out, overpowering any remaining new car smells with the unmistakable sour odor of geriatric vomit) and then his tobacco-colored Mark III Lincoln Continental, and head into nearby Manhattan. We’d usually stop along the way at a “Hot Bagels” store along the freeway on the outskirts of our home in Great Neck, New York. We’d pick up a bag of assorted bagels and bialys--my favorite being thick kosher salt-encrusted bagels--and then continue our journey into the City, the looming Manhattan skyline beckoning from the Long Island Expressway like the Emerald City along the Yellow Brick Road in The Wizard of Oz.

Entering Manhattan via the Queensboro (59th Street) Bridge, we’d wind our way downtown to 32nd Street, between Sixth and Seventh avenues, around the corner from Pennsylvania Station and the old Willoughby’s camera emporium, and look for a parking space. A row of oxidized green arched overhead walkways connecting several buildings along 32nd Street would serve as our landmark. Just before we reached the first overhead span, we would enter an old building and take a rickety service elevator up several flights (on subsequent trips, Drew and I would forego the elevator, choosing instead to race each other up the stairs, the staccato of our eager footsteps reverberating like the sound of gunshots against the stairwell walls as we jockeyed for position). Flush with anticipation, we barged into a large storage room like bulls entering the ring. We had arrived at what we would affectionately call the Back-Issue Store.

More of a dingy warehouse than an actual store, the name of the floor-length storage space was Jay Bee Back-Issue Magazines. To my brothers and me, though, it was like stumbling upon Shangri-La in midtown Manhattan. The space contained a treasure trove of out-of-date comic books, magazines, newspapers and other assorted memorabilia from a bygone era, all neatly arranged in seemingly endless storage bins.

No one can recall how we discovered the Back-Issue Store. My father claims that he might have first learned about it from Stan Lee. This is a plausible enough explanation, since for years they sat near one another at adjacent cubicles, separated only by thin white dividers. My father worked until the mid-Sixties as editor of a series of men’s adventure magazines at Magazine Management Co., which shared office space with the smaller, then-fledgling Marvel Comics. Our parents were always coming up with new, inventive ways to entertain us on weekends—Coney Island and Palisades amusement parks, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus, Broadway musicals, monster movie double features, Yankees and Mets games, penny arcades along Broadway and visits to cavernous Manhattan bookstores--so taking us to a warehouse stocked with old comic books and magazines was something that would certainly appeal to us. We would occasionally visit our father’s office along Madison Avenue in midtown Manhattan where we were always encouraged to grab a handful of Marvel Comics off the waiting room table. I already knew about the DC Comics superheroes Superman and Batman, mostly from watching television cartoons and the reruns of the ‘50s-era live action Superman series starring George Reeves and the campy mid-‘60s Batman series with Adam West. Visiting my father’s office was my first exposure to a newly emerging lines of comic books including The Amazing Spider-Man, The Fantastic Four, Dr. Strange, The Hulk, The Mighty Thor and The Invincible Iron Man, and we’d receive new Marvel comic books literally hot off the press. While I enjoyed looking at the colorful covers, I was too young to pay much attention to the actual stories inside, although I would soon take notice of the same Marvel superheroes that started appearing regularly in cartoon form on afternoon and weekend television, created by the same stable of classic Marvel artists including Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko.

Upon entering the Back-Issue Store, we were greeted by a bored-looking burly man with a goatee and his rangy, long-haired assistant who sat behind a beat up, cluttered wooden desk with an old-fashioned cash register (my father would later make the observation that there was a certain “look” to comic book salesmen: slightly pudgy, somewhat pale from lack of sunlight, and typically unkempt in personal appearance). The Back-Issue Store salesmen would eye us suspiciously, no doubt concerned that we might cause a ruckus or worse yet, steal things. But over time, after repeated visits, they would come to accept us as we became some of their best and most frequent customers. On any given visit we rarely saw more than a handful of patrons—mostly collectors in search of obscure magazines--and never any other children. Poorly lit narrow aisles with shelves contained stacks upon stacks of boxes and file cabinets towering toward the ceiling, each box or cabinet with the names of its contents scrupulously listed on the outside. Grime and dust seemed to settle everywhere, and the smell of mildewy paper mixed with plastic permeated the poorly ventilated warehouse. Warped wooden floors seemed to creak and groan with every step. The place must have been a haven for rodents, and most likely posed a fire hazard as well, but was still nectar to our young noses as we freely paced the aisles. I recall finding back issues of Sports Illustrated, Field & Stream, Time, Life, Look and even Playboy, a magazine I was already somewhat familiar with, despite my young age, because of my father’s frequent contributions as a writer; tucked away out of plain site we would also discover such hidden surprises as nudist magazines showing men and women frolicking in the buff while innocently enjoying a game of volleyball, lounging by a lake and engaging in other seemingly innocuous outdoor activities. I may have taken a few furtive glances inside, but these magazines held only passing interest to my brothers and me. There were dozens of other lesser-known esoteric periodicals as well, covering a wide range of topics from astronomy to mechanical engineering which we would quickly bypass. There may have also been several decades’ worth of old National Geographic’s, medical journals, as well as maps and lithographs. We’ll never know. Looking back, I regret having never fully explored the entire confines of the Back-Issue Store.

Upon entering the Back-Issue Store, we were greeted by a bored-looking burly man with a goatee and his rangy, long-haired assistant who sat behind a beat up, cluttered wooden desk with an old-fashioned cash register (my father would later make the observation that there was a certain “look” to comic book salesmen: slightly pudgy, somewhat pale from lack of sunlight, and typically unkempt in personal appearance). The Back-Issue Store salesmen would eye us suspiciously, no doubt concerned that we might cause a ruckus or worse yet, steal things. But over time, after repeated visits, they would come to accept us as we became some of their best and most frequent customers. On any given visit we rarely saw more than a handful of patrons—mostly collectors in search of obscure magazines--and never any other children. Poorly lit narrow aisles with shelves contained stacks upon stacks of boxes and file cabinets towering toward the ceiling, each box or cabinet with the names of its contents scrupulously listed on the outside. Grime and dust seemed to settle everywhere, and the smell of mildewy paper mixed with plastic permeated the poorly ventilated warehouse. Warped wooden floors seemed to creak and groan with every step. The place must have been a haven for rodents, and most likely posed a fire hazard as well, but was still nectar to our young noses as we freely paced the aisles. I recall finding back issues of Sports Illustrated, Field & Stream, Time, Life, Look and even Playboy, a magazine I was already somewhat familiar with, despite my young age, because of my father’s frequent contributions as a writer; tucked away out of plain site we would also discover such hidden surprises as nudist magazines showing men and women frolicking in the buff while innocently enjoying a game of volleyball, lounging by a lake and engaging in other seemingly innocuous outdoor activities. I may have taken a few furtive glances inside, but these magazines held only passing interest to my brothers and me. There were dozens of other lesser-known esoteric periodicals as well, covering a wide range of topics from astronomy to mechanical engineering which we would quickly bypass. There may have also been several decades’ worth of old National Geographic’s, medical journals, as well as maps and lithographs. We’ll never know. Looking back, I regret having never fully explored the entire confines of the Back-Issue Store.

While we roamed the Back-Issue Store aisles searching for old comic books and magazines, my father stood patiently by the front desk, engaging the two salesmen in small talk while keeping a watchful eye on the time; we knew we were on a tight schedule--usually no more than a half an hour--so we didn’t waste much time. We were also on a tight budget, so we tried to be as selective as possible in our purchases. As the youngest, I’m fairly certain there was some pleading and bargaining on my part with my father. Drew and Josh quickly zeroed in on the cabinets containing back issues of Famous Monsters of Filmland, Mad, as well as some other magazines I can no longer remember, while I set my sites on bins containing a seemingly endless supply of old Dell, Gold Key, Classics Illustrated and DC comic books from the late ‘40 through the mid-‘60s. I preferred the DC family of comics with such titles as Adventure Comics, World’s Finest and Justice League of America, which featured Superman, Superboy, Supergirl, Lois Lane and Batman and Robin, but also grew to enjoy Archie Comics, Casper the Friendly Ghost and Richie Rich.

Regrettably, all of my purchases from the Back-Issue Store are now long gone, with the exception of one item: a sealed copy of the second issue of Famous Monsters of Filmland from 1958, which proudly boasted on the back cover as being “the only magazine BANNED IN TRANSYLVANIA”; Josh has since unloaded many of his favorite Back-Issue Store purchases, including the first issue of Sports Illustrated, which included a foldout with dozens of replica early ’50s Topps baseball card cut-outs including a rookie Mickey Mantle. I suspect Drew has kept very little of his Back-Issue Store purchases as well.

While I wound up not saving any of the comics I collected from the Back-Issue Store, I still have the very first comic book I ever purchased with my own allowance: DC Comics’ Metal Men No. 28 from 1967, which I bought for 12 cents off a rack at a roadside convenience store in Amagansett, Long Island, where we were spending the summer; I also picked up some beef jerky sticks with the remainder of my 25-cent allowance. The cover depicted the alloy superheroes made out of gold, lead, iron, mercury and tin hovering dangerously above a boiling smelter while Tina, the sexy platinum Metal Woman, protected them from being totally submerged in the molten brew. I’m not even sure if I actually read the comic book; like a lot of children, I was probably simply drawn to the colorful cover artwork. Often, the stories did not live up to the expectation created by the sensationalist covers.

Our trips to the Back-Issue Store lasted for about a three-year period. While they may have enhanced my comic book fever, truth be told, we never really discovered any hidden treasures. Dreams of unearthing a mint-conditioned Action Comics number 1 from 1938 introducing the world to Superman or the original Detective Comics No. 27 featuring “The Batman” never materialized. Like a lot of children of the Sixties, we grew up hearing stories from our parents who wistfully recalled owning all the classic superhero comics from the golden age of comic books during the late-Depression years. My father had a particular preference for Captain America and an aquatic hero with superhuman abilities named The Sub-Mariner (who had pointy ears, dark hair, wore a bathing suit and resembled Leonard Nimoy’s “Spock” in Star Trek), who would re-appear years later under the Marvel stable of superheroes. It was a familiar story we would hear repeatedly from other children of our generation as well: By the time our parents had reached their teen years and had lost all interest in comics, their parents, seeing no redeeming value in these childish possessions, had thrown out all of their comic book collections, along with their toys. Who could predict that years later these same items would become valuable collector’s items in a burgeoning market for nostalgia? Each time our parents told us this, we would be aghast, wondering how they lacked the foresight to save such obvious treasures, which would be worth a small fortune in our eyes. Rather than discouraging us, though, this only steeled our determination to seek rare comic books on our own. My father would also tell us about the Big Little Books that he collected as a child, including such titles as Little Orphan Annie, Buck Rogers, Popeye, Mickey Mouse, Flash Gordon, Dick Tracy and Captain Marvel. He would lovingly describe their thick cardboard covers and the colorful artwork which would appear on each page opposite the text. Naturally, we added Big Little Books to our search for rare, old comic books.

Our trips to the Back-Issue Store lasted for about a three-year period. While they may have enhanced my comic book fever, truth be told, we never really discovered any hidden treasures. Dreams of unearthing a mint-conditioned Action Comics number 1 from 1938 introducing the world to Superman or the original Detective Comics No. 27 featuring “The Batman” never materialized. Like a lot of children of the Sixties, we grew up hearing stories from our parents who wistfully recalled owning all the classic superhero comics from the golden age of comic books during the late-Depression years. My father had a particular preference for Captain America and an aquatic hero with superhuman abilities named The Sub-Mariner (who had pointy ears, dark hair, wore a bathing suit and resembled Leonard Nimoy’s “Spock” in Star Trek), who would re-appear years later under the Marvel stable of superheroes. It was a familiar story we would hear repeatedly from other children of our generation as well: By the time our parents had reached their teen years and had lost all interest in comics, their parents, seeing no redeeming value in these childish possessions, had thrown out all of their comic book collections, along with their toys. Who could predict that years later these same items would become valuable collector’s items in a burgeoning market for nostalgia? Each time our parents told us this, we would be aghast, wondering how they lacked the foresight to save such obvious treasures, which would be worth a small fortune in our eyes. Rather than discouraging us, though, this only steeled our determination to seek rare comic books on our own. My father would also tell us about the Big Little Books that he collected as a child, including such titles as Little Orphan Annie, Buck Rogers, Popeye, Mickey Mouse, Flash Gordon, Dick Tracy and Captain Marvel. He would lovingly describe their thick cardboard covers and the colorful artwork which would appear on each page opposite the text. Naturally, we added Big Little Books to our search for rare, old comic books.

What we couldn’t find at the Back-Issue Store we sought elsewhere. Drew and I soon discovered a thrift shop not far from our home which had a bin by the front door filled with more current used comic books and magazines. The thrift’s manager, a crafty old codger, would coyly tell us that he would occasionally spot an early Action Comics or Detective Comics, but that we were always just a little too late. He cheerfully offered to sell us any rare valuable comics that we could find for the same price as any of the crappy comic books we typically found in the store: 10 cents each. “Even Action Comics number one?” I would ask incredulously, knowing its true soaring value thanks to Drew’s copy of the latest Comic Book Price Guide, with visions dancing in my head of the first Action Comics cover showing the Man of Steel holding a green car in the air. “Yup,” he’d reply without any hesitation. We thought we had pulled the wool over the old salesman’s eyes. Unfortunately, we never discovered any valuable comics, despite the old man’s entreaties to come back the next day, and we finally stopped returning after a number of disappointing visits.

Soon, my brothers and I would lose interest in the traditional superhero action comics genre altogether. But my search for comics would take an interesting twist. One evening in April of 1971, my parents dropped us off at the old Fillmore East concert hall on the Lower East Side. It was the first time I’d been left alone without my parents in the big city, and I remember feeling a sense of danger mixed with adventure. We went to see a Howdy Doody Show revival featuring the red-haired, freckle-faced marionette and the affable ‘50s-era TV show’s host, Buffalo Bob Smith. Before dropping us off, our parents issued stern warnings to my older brothers not to leave my side. Outside the Fillmore, a parade of hippies and street hawkers filled the teeming sidewalks. Soon after being dropped off, ignoring our parents’ warnings to stay put, my brothers promptly took me to a nearby magazine/head shop. And before I knew it we were looking at x-rated Underground Comix--avant-garde, uncensored, irreverent and wildly obscene comics that originated in San Francisco and had made their way to Manhattan. This was my first exposure to comics drawn by an emerging generation of counterculture artists such as R. Crumb, Spain Rodriguez, S. Clay Wilson, Gilbert Shelton and others who would defy all mainstream notions of what constituted a comic book. Apparently, Josh had been quietly collecting these comics during his frequent forays into Manhattan with his friends to see rock concerts at the Fillmore East, enjoying such bands as the Allman Brothers, Mountain, Cactus, Chicago, Grand Funk Railroad and a score of other seminal rock bands from the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Drew and Josh were also secretly buying Underground Comixs whenever we visited Bookmaster’s, a trendy two-story mega-bookstore (now defunct) on the corner of 59th and Third Avenue that also sold adult-themed counterculture books, records and movie and hippie-themed posters (I still have my subversive Richard M. Nixon Coloring Book from 1969).

Underground Comix were so out-there, however, that Josh and Drew wouldn’t dare show them to our parents, who were perhaps the most liberal and tolerant of all the parents we had ever encountered. My brothers had collected comic books with such titles as Zap, Bijou Funnies, Black and White, Hytone and Yellow Dog, each glorifying the hippie drug culture. The stories were satirical in nature, but were laced with explicit sexuality, were often misogynous, chock full of profanities, contained scatological humor, and were blatantly racist. Counterculture characters such as Fritz the Cat and Mr. Natural would soon become mainstream thanks to the growing popularity of R. Crumb’s Underground Comix. The artwork was also unlike any comics we had ever seen before, the closest being Mad magazine; simply put, they were raw, sophomoric, sick, and most importantly, often hilarious. Seeing these comics for the first time somehow set the stage for the Howdy Doody revival show to follow. Inside the Fillmore East, Buffalo Bob greeted the mostly long-haired audience which had been weaned on the Howdy Doody Show. “Say kids, what time is it?” asked Buffalo Bob, decked out in his trademark red-fringed buckskin outfit, repeating the show’s familiar opening refrain. “It’s Howdy Doody Time!” responded the appreciative, mostly stoned audience, which proceeded to sing the rest of the theme song in unison: “It’s Howdy Doody Time! It’s Howdy Doody Time!...” Buffalo Bob asked how everyone was doing in the “Peanut Gallery,” which led to another joyous response. A mushroom cloud of marijuana quickly filled the crowded theater like a ring of smog hovering over Los Angeles and I became dizzy from inhaling all the second-hand dope. In a nod to the changing times, Buffalo Bob would even crack a joke, feigning surprise in finding a pack of Zig Zag rolling paper, claiming it must have belonged to his old TV sidekick Clarabell the Clown. The audience went wild.

Around this time, Drew had discovered the EC (Entertaining Comics) line of science fiction, suspense, and especially horror comic books from the 1950s. These included such classic titles as Tales From the Crypt, The Vault of Horror and The Haunt of Fear, each featuring the familiar hosts—the Crypt-Keeper, the Vault-Keeper and the Old Witch--drawn in small circles on the cover. Drew would relate to me how alarmed McCarthy-era ‘50s government agencies and school boards would seek to ban these graphic comics because of their disturbing depiction of gore and horrific violence, which, naturally, only served to heighten our interest. Eventually a comic books code—not unlike the motion picture industry’s film code from the ‘30s--would be deployed by the comic book industry to self-censor itself from including content that was deemed too graphic in nature. Comic books which contained such words as “terror”, “horror” and even “weird” in their titles were forbidden, legislation clearly aimed at the EC line of comics and its iconoclastic founder, William Gaines, who would also launch Mad magazine around the same time. Many of these horror comics that were under fire and eventually folded by the mid-‘50s, were starting to resurface at comic book conventions a decade later, where they were now considered valuable collector’s items.

My brothers and I had an affinity for horror movies and monsters, so it was only natural that our interest would spill over into horror comic books as well. Since the late ‘60s Drew and Josh had regularly purchased and sent away for issues of the horror-comics magazines Creepy and Eerie from the advertisements in Famous Monsters of Filmland. I remember how excited they were when their magazines would arrive in the mail. My brothers even became official members of the Uncle Creepy Fan Club and Cousin Eerie Fan Club, each receiving honorary buttons drawn by the artist Jack Davis, plus an official membership diploma which they proudly displayed in their rooms. I was too young to fully enjoy the story content of these magazines, but I was always impressed by the wonderful cover illustrations, especially those painted by the legendary fantasy comic book artist Frank Frazetta.

Unknowingly, we had our first taste of EC comics when Josh had purchased a paperback in the mid-‘60s called Ray Bradbury’s The Autumn People—Stories of Chilling Horror by the King of Fantasy. I remember the haunting cover illustration which showed zombie-like creatures rising from the ground beside an old tree under a misty harvest moon. The paperback was basically a reprinted collection of Ray Bradbury stories that first appeared in the original 1950s EC horror and science fiction comics.

Soon after moving into Manhattan in 1972, Drew and I would begin attending comic book conventions held in midtown hotels and convention centers. By now, Josh had lost all interest in comics, focusing instead on his guitar playing and writing. Armed with the latest Comic Book Price Guide, Drew and I would scour the convention halls looking for the best values, often meeting and obtaining autographs from some of Drew’s comic book artist heroes. He would serve as my personal guide through this strange world of comic book collectors and dealers, steering me in the direction of the most innovative and interesting new and old-time illustrators, as well as those comics that would most likely become collector’s items over time. At first, most comic books looked pretty much the same to me, but I soon was able to discern the more talented illustrators from what Drew would dismiss as mere hacks, those artists whose boring work would not stand the test of time. An artist like Frank Frazetta, for instance, was more like a classic painter, with an instantly recognizable style which was apparent even in his earliest work.

Soon after moving into Manhattan in 1972, Drew and I would begin attending comic book conventions held in midtown hotels and convention centers. By now, Josh had lost all interest in comics, focusing instead on his guitar playing and writing. Armed with the latest Comic Book Price Guide, Drew and I would scour the convention halls looking for the best values, often meeting and obtaining autographs from some of Drew’s comic book artist heroes. He would serve as my personal guide through this strange world of comic book collectors and dealers, steering me in the direction of the most innovative and interesting new and old-time illustrators, as well as those comics that would most likely become collector’s items over time. At first, most comic books looked pretty much the same to me, but I soon was able to discern the more talented illustrators from what Drew would dismiss as mere hacks, those artists whose boring work would not stand the test of time. An artist like Frank Frazetta, for instance, was more like a classic painter, with an instantly recognizable style which was apparent even in his earliest work.

While I enjoyed reading comics, Drew was passionate about them. Not surprisingly, he would grow up to follow his childhood heroes by becoming an illustrator himself. Comic book illustrators were the equivalent of his sports stars, and he developed an encyclopedic-like knowledge of their statistics. Beyond the obvious artists who were household names, like Charles Schulz of Peanuts, he introduced me to such artist luminaries as Jack Kirby, Basil Wolverton, Bernie Wrightson, Will Eisner, Wally Wood, Harvey Kurtzman, Neal Adams, Jim Steranko, Jack Davis, “Ghastly” Graham Ingels, Al Feldstein, Joe Orlando, Johnny Craig, Reed Crandall and Frank Frazetta. Why I still remember these names, nearly 35 years after having last seen their actual work, is not only testament to the superior quality of their artwork but, more importantly, to Drew’s influence on my interest in comic books.

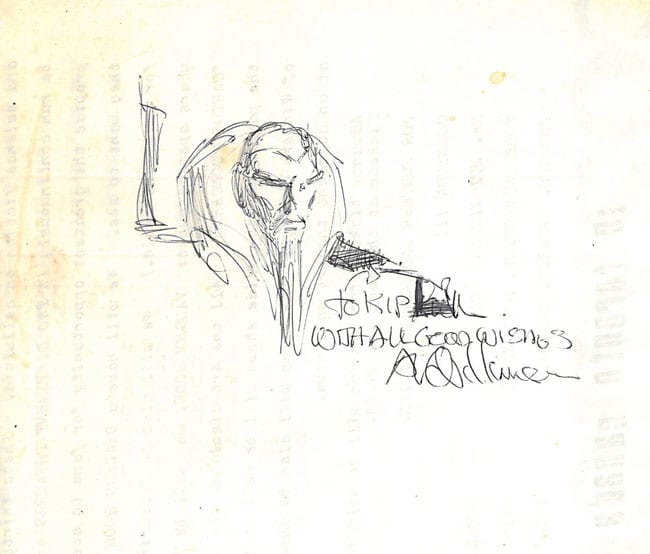

I still have an autograph from the prolific comic book artist AlWilliamson,including a quick illustration he made for me of Flash Gordon’s arch nemesis Ming the Merciless. While Drew may have framed such items as important artifacts, I simply stored them on a pile with my comic books, quickly forgetting about them. For a time, Drew had instructed me to buy number ones of all new DC and Marvel comics, and to promptly seal them in air-tight plastic wraps because someday these premiere issues would be valuable to future collectors. Clearly, he wanted to avoid the same errors that our parents had made as children. Based on his recommendations, I eagerly picked up the following number ones: Conan the Barbarian; Swamp Thing; The Shadow; Kamandi, the Last Boy on Earth; Chilling Adventures in Sorcery; and probably the most important purchase of all, the much-hyped Shazam, the Original Captain Marvel which, Drew assured me, would someday be worth a small fortune. Perhaps my favorite purchase during this period was The Demon number 1, which was loosely based on the Arthurian legends of Camelot, beautifully drawn by Marvel Comics veteran Jack Kirby, who had caused a minor stir in comic book circles by jumping ship to DC Comics. I also picked up Plop number 1, the “New Magazine of Weird Humor,” featuring the freakishly delightful cover artwork of long-time Mad magazine contributor Basil Wolverton.

Along the way, I also started acquiring original EC horror comics from the ‘50s. None of these comics were in very good condition (they had a distinct old-paper smell, as if they had been left unattended for years in a box in someone’s attic), and were probably unwise investments, but it was thrilling nonetheless to acquire the originals. Each time I removed a fragile copy from its protective plastic sheath, lifting the taped lip, I risked further damage to the comic. I would invariably chip a fading edge, undermining its value. But somehow that didn’t bother me. I once made the mistake, however, of purchasing for $5 an original Vault of Horror number 30 from 1953 (known as “the dismemberment cover”) with a third of the cover cleanly torn off. The remainder of the cover showed an arm severed down to the elbow socket still clenched to a subway overhead handrail while rush-hour passengers look on in abject horror and disgust. Drew was clearly upset--not by the shocking cover, beautifully illustrated by EC veteran Johnny Craig--but that I would be so stupid as to waste my money on a damaged comic that was basically worthless as an investment. He would bitterly complain to my father, who would later half-heartedly reprimand me, more so, I suspect, to placate Drew.

I once made the mistake, however, of purchasing for $5 an original Vault of Horror number 30 from 1953 (known as “the dismemberment cover”) with a third of the cover cleanly torn off. The remainder of the cover showed an arm severed down to the elbow socket still clenched to a subway overhead handrail while rush-hour passengers look on in abject horror and disgust. Drew was clearly upset--not by the shocking cover, beautifully illustrated by EC veteran Johnny Craig--but that I would be so stupid as to waste my money on a damaged comic that was basically worthless as an investment. He would bitterly complain to my father, who would later half-heartedly reprimand me, more so, I suspect, to placate Drew.

Disregard for taking good care of my comic books proved to be the eventual undoing of my comic book fever. Unlike Drew, who painstakingly sealed his comic books, lovingly protecting them from the elements and stocking them in order on neatly arranged book shelves, even going so far as to catalogue his collection, I simply left my comics haphazardly in a pile. Drew would continue to attend comic book conventions, but he probably sensed my flagging interest and went without me. Family moves lead to further marginalization of my comic book collection. I was obviously more like my parents after all, quickly losing interest in comics as I grew up. Most of my comic books wound up stored in boxes, tucked away in closet spaces until I eventually sold them while in college, far below their Comic Book Price Guide market value, to comic book dealers who promptly inflated their price tags.

Looking back, it’s hard to believe the hold comic book fever once held over my brother and me. I recently found a postcard that Drew sent to me while I was attending Camp Emerson in Massachusetts during the summer of 1973. Throughout the summer, Drew had been sending me care packages filled with mostly comic books and I must have written him back at one point to thank him, when he wrote back, "Dear Mr. Flip [one of the pet names he used to call me], today is the 14th. You come here in around 10 days. On the 25th of August believe it or not there is a comic book convention in Amagansett at the American Legion Hall…You will probably get around 1 more package of comic books. Daaa!! I will just come out with it and say that the surprise you’re getting is an E.C. comic. Don’t expect no Vault of Horror #12. It ain’t that old. You will see when you get here.“ He had drawn two bizarre faces on the postcard, one of a portly, freckled man with neatly parted hair, separated by a cowlick, wearing a tie which was placed opposite the 8-cent stamp, and a smaller profile of an ugly woman with a bulbous nose and jutting chin within the text. He ended the postcard, “P.S. Who cares about your stupid rockets?"