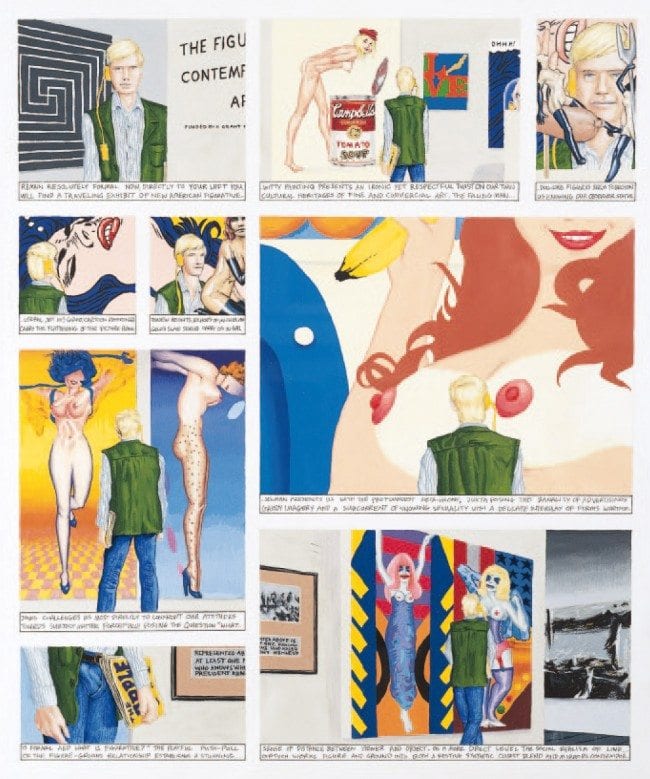

Last fall Jim Shaw published My Mirage (JRP|Ringier, 216 pages, $55.00), a hybrid visual book somewhere between a visual novel, a monograph and a work of omnivorous visual criticism. It collects almost 170 works of art executed between 1986 and 1991 in nearly every medium imaginable. It is an astounding book, perfectly produced, and one that ought to be poured over in comics and art circles for its conceptual and visual ingenuity, emotional heft, and the histories embedded within it. Over the years the My Mirage pieces have been exhibited as a whole only twice, and otherwise it's been subdivided into smaller groupings hung in galleries and museums. The prints, photos, videos, paintings, drawings and sculptures that comprise My Mirage are each that rare thing: objects that work in space and as part of a book-length narrative. My Mirage (the book and works) is the story of Billy, a kind of zelig of visual culture, who lives out his life through the prism of the culture around him, and manifests each phase of his life, almost like a cultural symptom, through complex reimaginings of artists including Ed Ruscha, De Chirico, R. Crumb, Basil Wolverton, Jess, Jack Chick, Hieronymous Bosch and many, many others.

Billy begins as a repressed boy of the 1950s and grows into and out of hippiedom, 1970s decadence, paganism, and fundamentalist Christianity. We follow Billy and his/our culture as he/it moves through different areas of art, making My Mirage a locus for a truly advanced sense of visual history. Two decades before it became acceptable to do so, Shaw makes no foolish high/low distinctions, imbuing as much meaning in Big Daddy Roth as he does John Baldessari. And so in My Mirage we can glimpse the entirety of visual culture through Shaw's eyes, but not as static, museum-ready artifacts. Rather, in its evocation of the power and corresponding psycho-social effect of these artists and forms, My Mirage shows what art can do. In that sense it finds its only real prose corollary in Geoffrey O'Brien's Dreamtime, another book charting an emotional/psychological evolution via the experience of art.

Through it all, as the book's editor/curator Fabrice Stroun notes in his excellent essay (precisely pitched as an elegant commentary with graphically compelling typography) Shaw maintains a kind of neutral surface. No one work is an exact facsimile -- instead all are given an even, almost blank feel. That allows Shaw to be the dominent author, and us to sink into the work without worrying after the particulars. And that's a very comic strip/book way to go at it -- applying an even line, let's say, to make it all cohere. In terms of the comics medium, My Mirage is especially important for what it implies about the cultural narratives embedded in comics, and how those narratives might be teased out to greater and greater effect as they intertwine with other parts of visual culture. Moreover, as a picture story there's never been anything like it -- Shaw ambitiously allows only a skeletal linear narrative and instead forces us to engage with it as a book, a story, a collection of objects, and a culture, with all of the contradictions that combination brings with it.

Shaw (born 1952) has a long history with his source material, having begun his career in Ann Arbor Michigan, immersed in the trash culture around him and transmogrified it as a member of the Destroy All Monsters collective in the 1970s (the subject of an exhibition I co-curated with the late Mike Kelley a few months back). He then attended the California Institute of the Art at the height of the conceptual movement, and began showing in galleries in the 1980s; in the meantime he worked in special effects for film and television, including Earth Girls Are Easy (1987) and even an early version of Terrence Malick's film Tree of Life. My Mirage is one part of Shaw's exceptional body of work, including his landmark Thrift Store Paintings exhibitions and book and his more recent work involving a fictional religion called Oism, which includes multiple comic books presented on gallery walls. He has exhibited in museums and galleries internationally (even crossing into comics as a guest at Fumetto) and will open a show at Metro Pictures, New York, on March 17th.

I emailed with Jim Shaw in January to discuss My Mirage.

As published, My Mirage has taken on the feel of a sequential visual novel, but I know it was created over a number of years in a non-linear fashion. So, was it ever all mapped out on paper or in your head? Was there a grand plan for it?

I always conceived My Mirage as a book and narrative about coming of age in the '60s done in a fragmented, Burroughs-influenced style using as many different aesthetics as I could muster. Originally it was to be five chapters, about 100 pieces, but during the making I had an idea to expand it with a video per chapter, and there were 3 pieces I felt I needed to eternally research before I felt ready to execute them. So the time frame got stretched way beyond the initial couple of years as my delaying those pieces led to new ideas for further pieces. There are a number of pieces not included in the book because the publishers wanted to stick to only pieces I had good quality 4 x 5s of. I intend to create a web access for those other pieces, but have no idea how, or time or money to pay someone else to do it.

Which three pieces hung you up, and why? And what does research entail for you? Do you practice the rendering method or is it all observation?

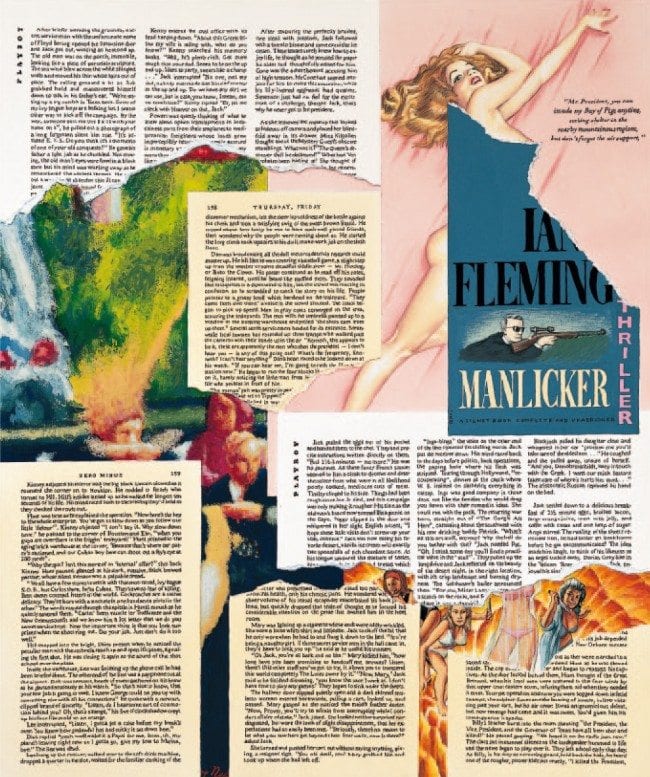

Well one was “Mannlicher” [below] which was JFK’s life in the style of Ian Fleming and the aesthetics of its Playboy-excerpting and paperback versions, with a page out of a supposed E. Howard Hunt thriller thrown in to give the assassin's POV. Another was the Bosch piece ["Chicago 68"] in which all the symbolism, instead of reflecting the concerns of a Dutch Christian in the Renaissance, comes out of Beatles psychedelic lyrics, conflated with elements of the 1968 Chicago demonstrations. I’m not sure what the third one was, perhaps the 4th video…

You have a perverse relationship to picture stories. My Mirage is a series of free standing art objects that can be "read" as a book; and you've completed "comic books" that exist not as publications but as "original art" displayed on walls. How did you arrive at this peculiar paradox? And why have none of the comic books been published as such?

There was a move afoot to publish my earlier Oist pieces, but I wanted to do all the color design, and never had a break from all the shows I've had to do to pay the bills. Now I'm doing a succession of four more Oist comics, and I also have an unfinished project to do all the comics I dreamt of that's been long delayed. Fabrice Stroun [of JRP] would love to publish them, and so would I, but they are a difficult sell as art objects, since we're talking about 20 pages sold together in a "debased" and disrespected medium. After seeing the Sistine Chapel and thinking how radical a piece of art it was and so wanting to work in the figurative, I realized that comics are one of the only art forms where the figure has any legitimate use, so I'm glad to be working in it, and I've finally graduated away from needing to use photo reference to draw them.

What do you mean "legitimate"? You yourself still make figurative paintings, as do some of your peers.

Maybe "only" and "legitimate" are overblown, but I do think that to do a painting of a figure posed ala the Sistine Chapel would be either ironic or pandering in the present, so maybe "unironic" could replace "legitimate."

There's some bitter irony here that you can make comics for the wall but not for publication. A twisted inverse of the pop paradigm. Is it different to stand and read "drawings" than to sit and read "comics"? Does your friend Robert Williams ever give you shit for this work?

I know that Ditko is adamantly opposed to comic art being shown on gallery walls, and that I get antsy trying to read a lot of text on the wall, and my ultimate goal is reproduction for any artwork I produce. I grew up experiencing art in books and magazines, and it’s still the main way I see stuff. Williams hasn’t given me any shit for doing comics, and I think he mostly gave up drawing them because his narrative urges were better expressed now in paintings. I’m glad to see him return in newer pieces to the inked line, something I was missing in the paintings.

Tell me about Billy as a protagonist. Who is he?

Billy is an amalgam of myself and my friends back in high school, but he's basically a cypher for the American puritan pilgrim traveling through adolescence in the land of '60s sin, drugs, beat-off material, rock'n roll, TV, etc.

One of the many compelling parts of My Mirage is its vision of visual culture as a place without high/low distinctions. That seems to mirror your own experience as an artist and collector. Is My Mirage an attempt of your own to create a lineage for yourself? Is it a kind of canon? And if so, have you been tempted to do a pure, explicitly curatorial project, or is that less interesting than synthesizing the work? I think here, for some reason, of "Faithful Cad", which has the effect of working with both Jess and Gould -- a neat doubling almost impossible without this kinda work.

Among my goals with the series was to effect a story through as many different media, aesthetics and types of storytelling as I could muster. There were a few pieces I knew I wanted to do from the beginning when I planned for about 100 pieces, all 14 x 17, that I always felt like I needed to do more research before I was ready to tackle. (Like I am now with The Book of O). This led me to have a number of further ideas, including a set of five videos (the Sinbad piece remains undone), so the series expanded to around 170 pieces. I was attempting a visual version of what Burroughs achieved in the cut-up method, but I would provide all the material that was to be cut up. I also tried to make the medium and the story match up in as many ways as possible, since this was my first big "novel". So, a piece entitled "Watercolor" was a story about nearly drowning at the city pool, the water that trickled underneath the floors of the changing room, and the exposure to women's pubic hair done in watercolor; or a piece in the style of Wes Wilson's Fillmore posters, based on Munch's Madonna, featuring Billy's dream girl in that pose, which resembles Wilson's earth mothers, and text from the lyrics to "I Heard Her Call My Name" by the Velvet Underground in place of the band names and performance details of a real Fillmore poster.

I’m fine with all sides of the culture. At the opening of the Kustom Kulture show there was a guy in a Big Daddy Roth outfit who would occasionally blast an

"a-ooga" type car horn, and it really did unsettle the high art types he was so obviously suspicious of, which is actually quite hard to do as our culture can coopt and absorb all kinds of rebellious activity.

And was there ever a plan for the sources of My Mirage to be shown?

It would be really hard to encompass all the sources. Maybe I should do digital walk thru where I explain all the arcane references. It'll be the same time as I do the color separations for the comic pieces.

Hippy culture has a profound impact on Billy and My Mirage -- and you manage to suss out the raw power (pun intended) inherent in the imagery and correspondent lifestyle. What made it so intriguing to you (and Billy)? And did punk pass you by?

I was as close to a hippie that a middle class kid who lived at home in a small city in Michigan could be. My dream in '67 was to move to Haight Ashbury and have my hair as close to Hendrix as I could get it. The problem began with Woodstock, where the same people who were spitting at me a year earlier were wanting get in on the perceived sex drugs and hedonistic lifestyle they imagined us to have achieved (nobody got laid in those days). I didn't become a hippie to have the whole world join in, but to make plain that I was a weirdo. My friends all revered Zappa and we retained the cynical attitude of the first hippies (the cynics were rebellious youths in ancient Athens who acted like dogs and mocked society). Manson came along and made a mockery of the rhetoric of hippiedom, Nixon was president, we were all punks with long hair. Moving to Ann Arbor reinforced my resistance to the peace and love thing, as we had on one hand gnarly street people (i.e. crazy homeless people), and nascent yuppies on the other pursuing the hedonistic end of it all, listening to Dan Hicks instead of the Charlatans, smoking pot and building resumes.

The choice to tell Billy's story via the media that engulfs him and transforms him (and which you in turn transformed) is very much a late 20th century move. It seems like you're both celebrating the daily onslaught and warning against it. Or both. What are the ups and downs for you?

When I was a kid, I'd do my homework and listen to music, something unimaginable to me today. My own daughter becomes a zombie when the TV is on, and was so addicted to tweener sitcoms that we had to get rid of our cable. Unfortunately she just discovered digital downloading via her WII. The media today is a million times as enveloping as it was in the '60s. TV was small, black and white and fuzzy: McCluhan's cool medium. Today there are several 24-hour kid's networks in high def, way more actually watchable shows, and stuff that panders to every interest group (except maybe artists). Video games activate the brain like a pinball game on steroids. Kids who act up in class will be force fed ADD drugs; how could you emerge unscathed from all that? Back in the 1800s the Bible was the main frame of reference and one's attention was not taken away by any mechanical medium, unless they had player pianos in those days. That's one of the elements I was contemplating in My Mirage: how rock 'n roll replaced the Bible as a moral point of reference for most of us in mainstream America, a country that was largely like Afghanistan 60 years earlier.

Hmm, how puritan do you think America was? Did you consciously fight against nostalgia and easy ironies -- you avoid both at every turn, so I wondered how much of a struggle it was. Do you mind nostalgia?

I am still listening to music from my youth (which ended with post-punk sometime in the early '8os, apparently), as well as stuff from the '20s, '30s, '40s, '50s, etc. I don't know how much of it is nostalgia, but I was eager to get My Mirage up and running as I knew it was inevitable that there would be a '60s revival someday. I started coming up with the concept and researching around 1980, and first exhibited stuff in 1986. I'd been working in special effects at companies like Midocean and Robert Abel's doing glitzy '70s-'8os TV commercial effects (will Mad Men ever reach that coke-addled era?) and I had an older girlfriend who'd started as a beatnik (her high school boyfriend took her to the EC offices about the time they'd collapsed) who encouraged me to retain some of the positive aspects of the '60s rather than trashing the whole era, and my researches began. I also began finding out about the utopian Christian communes of the burnt over district in the 1820s, and later that inspired the background of Oism.

I don't know anything about these communes...

There were a number of Christian and other communes, many in the upstate New York and northwest Pennsylvania area, the west coast of it’s time. The first was called The Woman in the Wilderness, after a figure from Revelations. There was a community on Keuka Lake called New Jerusalem that I found out later was renamed Branchport and was a short walk from my grandfather’s cottage. It was fronted by a woman who called herself The Universal Public Friend, and claimed to be the reincarnation of Jesus, and whose death was hidden from the followers by her lieutenant/boyfriend. Mormonism was founded to the east of Rochester, to the west was the Oneida, a “Free Love” community that lives on today as the silverware manufacturer. The Shakers, started in England ended up nearby. Feminism, spiritualism, and the abolitionist movement were spearheaded in the region. Further afield in Iowa was the Amana colony, where microwaves eventually emerged from the ether. In Oism I appended elements of anti-slavery, feminism and theosophy to the brew in Annie OWooten’s head as she channeled the book of Oism.

Aren't you going to ask me about comic books?

Oh, sure. Let's go. Who is your favorite inker? Who do you like most for narrative flow? Did you ever find much to latch onto in underground comics, or were '50s and '60s SF and Superhero stuff freaky enough? What is your favorite Wally Wood period, and why? Wayne Boring or Curt Swan? What comic book do you most wish existed that does not, as drawn by a real and beloved artist?

My family has always had a too-strong loyalty streak and as a kid I began with DC Comics, since Marvel was at the time just a step up from Charlton with its monster comics and murky colors. So I stuck with DC, having graduated from the more primitive comics -- Superman and Batman -- to the more "sophisticated" (their heroes were all scientists), Flash, Green Lantern, Atom, Hawkman, Adam Strange. So Murphy Anderson inking Carmine Infantino was my favorite. I realized the imagination at Marvel was far superior as their superhero comics began to appear, and I obviously valued Dr. Strange as the pinnacle of comic creation at the time. Now, I have a perverse fondness for the creaky DC plots, predicated as they were on startling, surreal cover images explained by insanely rational plots which often hinged on some scientific fact, like a chemical reaction.

Over time I saw more of the EC work, and Wally Wood was a presence through Mad and reprints- his women defined my ideas of attractiveness even before I saw Playboy (kinda sad, huh?). Of the EC artists, I think Johnny Craig had the best combo of drawing and storytelling, while Kurtzman was obviously the best at sequencial narrative. Now that the world of reprints is gearing up, I can see that I was missing out on the best work of Bob Powell and Bill Everett. It seems that the code wiped away the best instincts of many artists, and it seems from their bios, many were alcoholics whose talents would dissolve away as they might have grown. And then there's Herbie and Katy Keene and all the odd things comics in their mindless production can create almost by accident.

Kirby did his best work in the '70s after 30-40 years of comics. This gives me some hope as I approach 60 myself. Wood did great work at many periods... It was revealing to me to see his and Craig's early comics, as five years in the trenches made them much better artists, they didn't just pop out of the womb as masters.

Wayne Boring's work has a sad poetry to it. The way he drew Superman as a stolid middle aged guy with a wide trunk, the many stories of tragic lost loves, and then to realize he was paid by DC to essentially change the look of Superman since they were being sued by his creators at the time. Curt Swan was obviously a superior artist at drawing realistic faces and expressions, but then he represented the pinnacle of the corporatization of the line, of the lack of vividness, culminating in the company's absorption by Warner Brothers. In researching Boring I found some caricatures he did of his old boss at DC and they were quite good, showing an ability at humor that almost never got an outlet in Superman.

The undergrounds were a continuation of my love of comics, and a bit of an enabler to maintain a childish interest past childhood. The Zap artists and Binky Brown are to me the best of the lot, no surprise. R. Crumb , after starting the whole thing, is still going strong. His Book of Genesis is very good, but it means I can't pursue my idea of doing a comic version of the book of revelations. Let's not forget Chester Brown and Dan Clowes and Alan Moore and I'm sure there are lots of other post-underground comics that I don't have time to read.