Falling into oblivion: admirers & beginnings

Lance and the life of its creator, Warren Tufts (1925–1982), are full of paradoxes. Some sequential art connoisseurs firmly believe that Tufts created two of the most beautiful Western comic strips of all time: Casey Ruggles and Lance. However, for many years Tufts’s work was almost forgotten. Ervin Rustemagic, a Bosnian comic book publisher, distributor, and rights agent, states in his book, Čudesni svijet stripa (The Miraculous World of Comics, 1975), that initially there were not even plans to include a separate entry on Warren Tufts in Maurice Horn’s The World Encyclopedia of Comics. Rustemagic had helped create a renewed interest in Tufts’s work by publishing it in the ‘70s, and subsequently Horn asked him to write Tufts’s entry. This veil of oblivion hovering over Tufts’s work was reinforced by the many collectors of Tufts’s originals and strips, who unsuccessfully tried to contact him. Some speculated that Tufts had died in the ‘60s, some that he had never existed and that it was a pseudonym of another artist. Some even suggested that Tufts was the brother of fellow cartoonist Alex Raymond. James Herbert (1943–2013), one of the best-selling horror writers in the world, was a devoted admirer of Tufts’s work, and he claimed that there was no writer in the world who was better at action and staging a plot. Herbert felt that everything he had achieved in his life he owed to Tufts, and that his Sundays and dailies were the best drawing and writing school around.

Warren Tufts never had any formal art or drawing education. He was born on December 12, 1925 in Fresno, California, and as a boy and member of the Scouts, he toured the Mother Lode country of California that extends northeast of Fresno on the Western slopes of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, a historic area where the gold rush began in 1848. Tufts’s father was also a great lover of nature, a man of the open spaces, who passed on this passion to his son. These two factors strongly shaped Tufts’s personality and later affected his creative passions. Tufts described his father’s role as a deep, never verbalized influence on him and his creative work.

At the age of 14, Tufts began working for a local radio series, where he first got to test his voice, acting, script writing, and production talents. Later the same year, he became the manager of a local advertising agency. After high school, Tufts went into maritime aviation and made his first illustrations for military publications during the Second World War. After his return to civilian life in 1946, he joined a friend and established several radio stations, until they went separate ways when Tufts decided to try a completely new path — the newspaper comic strip. He was 23 years old.

Casey Ruggles

For three months, Tufts read reference literature: books on exploring, writing, sketching, and drawing for his future Western feature, Casey Ruggles. He then submitted test pages to King Features Syndicate and United Features, but they both passed. By chance, he contacted the editor-in-chief of the San Francisco Chronicle, Larry Fanning, explaining his project and showing him the first pages. On Fanning’s strong recommendation, the United Features Syndicate thus decided to sign and promote Casey Ruggles. Weekly Sunday pages began syndication on May 22, 1949, the daily strips on September 19. Until January 8, 1950, Sundays and daily strips carried the same storyline, but on Monday January 9, 1950, the daily and Sunday storylines went in separate directions, each following the adventures of ex-soldier Casey Ruggles in 1848, at the very beginning of the California Gold Rush.

Bill Blackbeard (1926–2011), a man known for preserving the treasures and history of newspaper comics, defending comic strips as worthy of study, stated in 1976 that Casey Ruggles was “unquestionably the finest Western adventure strip yet created.” Blackbeard built his argument on a series of revolutionary changes introduced by the comic strip. Above all, Tufts thoroughly investigated the period he was writing about. The strip brings to life powerful portraits of characters, including real historical figures. It’s also a brutal, bloody, and dynamic strip. Tufts initially created it as a graphically overwhelming colored Sunday page, but Casey Ruggles stunned its readers of the early fifties as it evolved into a truly serious comic drama, which creativity nobody else could match. If readers were annoyed, their letters of protest focused on the graphic display of torture and rape, themes otherwise inconceivable in the syndicated comic strips of the time. Blackbeard wrote that Casey Ruggles should be considered a graphic novel of several volumes, reprinted and sold as such.

A workload of 80 hours a week, writing and drawing both the Sunday pages and the daily strips, soon exhausted Tufts. He had met Alex Raymond only once, when he began working on Casey Ruggles, and recalled the meeting in this way: “I got the impression that he thought I was some kind of crazy because I wanted to write and draw both the daily and weekly version of the comics at the same time. He was a smart man. He was right.” (Nema više Vorena Taftsa / No More Warren Tufts, Ervin Rustemagic, Strip Art # 25, Sarajevo 1982). Meeting deadlines was getting increasingly difficult, and it became necessary to rely on assistants, some of whom were Tufts’s personal choices, such as Alex Toth, Wally Summers, and Fresno Bee, while others were imposed on him by United, such as Rueben Moreira, Nick Cardy, Edmund Good, and Al Plastino. As Tufts’s frustration grew, his great interest in the California Gold Rush suffered, and his research journeys could no longer be prioritized; Tufts was strapped to the drawing board, imprisoned in his studio by his deadlines. Despite his great love for drawing and Casey Ruggles, paradoxically, he felt that he had fallen into a trap.

However, the biggest disappointment was Tufts’s failed efforts to attract studios interested in turning Casey Ruggles into a TV series and feature films. United Features unrealistically raised the price, which made four production companies withdraw. In hindsight, it’s difficult to judge if this was due to an erroneous fear that a film or TV series would endanger the popularity of the comic strip — which, according to Tufts, was the reason for United’s actions — or if the syndicate became too greedy and thereby obstructed further negotiations. After five years, Tufts decided to leave Casey Ruggles. His final daily was published on April 3, 1954, his final Sunday on September 5 of the same year. United Features briefly tried to continue the strip, handing over the writing and drawing to Al Carreño, but the strip was soon cancelled. The reason was quite simple: No one was able to produce the kind of storytelling and artistry Tufts had created.

Satire of The Lone Spaceman

The Lone Spaceman was a short venture between Casey Ruggles and Lance, the project Tufts intended to embark on. This new comic strip was simply created to fulfill the terms of his contract with United Features, which required him to offer them his next comic strip. Only if he were rejected, he gain his freedom to continue with the strip on his own. He thus created the satirical comic The Lone Spaceman, a parody of The Lone Ranger. In this new strip, Tufts again touched upon difficult topics: politics and incest. He later said that this form of parody was not well received or understood, and that the readers who did understand were mostly high school and college students. Although this again was both a weekly and daily feature, Tufts described it as “quick and easy to work,” designed to last three or four months. The Lone Spaceman began on December 5, 1954 (a Sunday), and ended on April 16, 1955 (a Saturday). In an interview with Dennis Wilcutt (first published in Warren Tufts Retrospective, ed. by Henry Yeo, 1980), Tufts mentioned that it was a pity to cancel it, but that it did not generate enough income to hire an assistant and thus prolong its life. At that moment, 29 years old, Tufts was instead preparing another, incomparably more ambitious project.

Lance - an epic ambition come to life

There was no doubt that Tufts, embarking on his next comic strip project, would choose the familiar genre of the Western. The new feature was set in almost the same historical period as Casey Ruggles (1834–1847) and in a similarly magnificent environment, this time Kansas and Missouri. He decided, however, to raise the bar and quality of this future series — and aimed to create the Western genre’s equivalence to Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant. His ambition is reflected in the painstaking richness of the natural scenery, in front of which his racially, socially, and psychologically well-defined characters played dramatic roles, in costumes perfectly designed to the very last detail. A true reflection of the era. Hal Foster was one of the greatest masters of landscapes in the comics, and Tufts’s ambition was to stand side-by-side with Foster’s artistic genius. There are few draftsmen in the world who would have had the courage to try something like this, but Tufts did not suffer from lack of courage. He had already successfully drawn majestic landscapes in Casey Ruggles, which in hindsight was a stepping-stone, foreshadowing the creative authenticity of Lance.

Lance premiered on June 5, 1955, as a Sunday page painted in fascinating colors. Tufts’s father and brother were in charge of their independent distribution, and it was very well received by its readers. During the best period of its run, it was published in about a hundred newspapers, and Lance initially received an even better response than Casey Ruggles had.

Ambiguous classicist

In terms of storytelling and visual narration, Tufts wanted to cover “a whole range of human drama.” He succeeded in a somewhat different way than he might have originally intended. His initial intention was classically oriented, but his complex talents and temperament led him beyond a classic domain. Classicism refers to style, rules, conventions, themes, and sensibility, and as much as he wanted to respect the highest codex of rules and principles embodied in Hal Foster’s approach to genre and drawing, quite often, sometimes consciously, sometimes not fully aware, Tufts violated a number of genre rules and stereotypes.

An artistic perfectionist

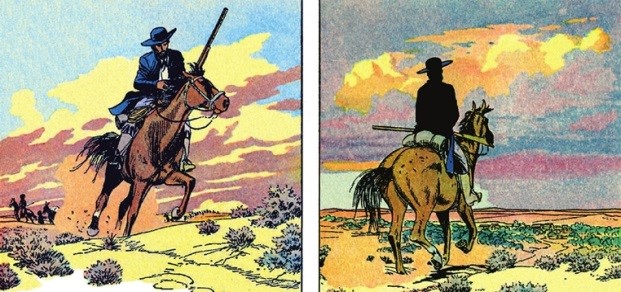

Tufts’s work was immediately stylistically different from the trend that changed the European Western from the mid-fifties. This “dusty atmosphere” was envisioned by artists such as Jijé (Joseph Gillain) in Jerry Spring, Jean Giraud in Blueberry, Hermann Huppen in Comanche, or Michel Blanc-Dumont in Jonathan Cartland. Tufts, on the contrary, was aiming for a more glamorous stylization, similar to the art Alex Raymond created during his 1940s run on Flash Gordon. There are a slew of comics artists who can be characterized by this type of stylization. They include: Warren Tufts, Dan Barry, Sy Barry, John Romita Sr., Paul Gillon, and Sergio Tarquinio. All are cartoonists whose comic art is striving for elegance and “glitter like after the rain.” Imagine that the drawing perfectionism of Space Prison (1951–1952), the cult episode with which Dan Barry began his work on the daily Flash Gordon, was maintained during the full run of an entire series, or in our case, over the course of five years, and you would get — Lance. It’s an unforgettable achievement of craftsmanship. The narrative intensity is accompanied by an equally impressive devotion to the drawing; episode follows episode at great speed, but what remains deeply engraved in our memories are individual stories, narrative vignettes and, of course, the characters.

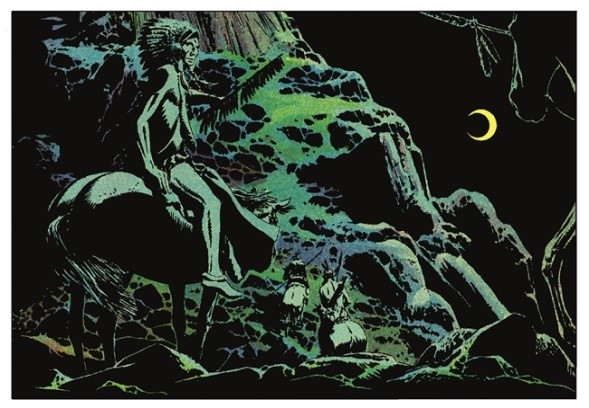

The glow of Tufts’s black surfaces in Lance is an even darker luminescent than the blacks created by Frank Robbins in Johnny Hazard or the blacks in comics created by Domingo Roberto Mandrafina. It’s a reflection of black velvet, a phenomenal use of chiaroscuro, and a powerful means of accentuation in Tufts’s otherwise colorful approach. Still, Tufts does not use it too often, and never as a mannerism.

At another side of the spectrum, we find the full-color experiment, three Sunday pages from May 27 – June 10, 1956 (pages 78-80), which he painted without the use of black ink. These are an extravagance in color usage and differ from the usual, truly “comic-like” scenes of the series.

A superficial observer may classify Tufts’s style in Lance as photorealism. But flirting with photorealism in comics hampers the dynamics of visual narration and thus one of the essential attributes of sequential storytelling. Tufts goes far beyond that. He created an extremely personal style which can hardly be mistaken for any other, and he disrupts the academic realism in at least two ways, dynamic and comical. He uses elements specific for the comics medium, such as motion lines that increase the speed and power of movement.

Lance is a comic strip of mesmerizing beauty. As a man of nature and open spaces, an outdoor man like his father, Tufts created Lance with an incredible respect for the adventure of life in the open. The landscapes, one of the key concepts in Lance, are a dynamic element of narration. The succession of outdoor scenes, the dynamics of changing weather conditions, and the passage of time over a day are stunning. Everything is on the move and pulsates with the rhythm of the story.

A few comparisons

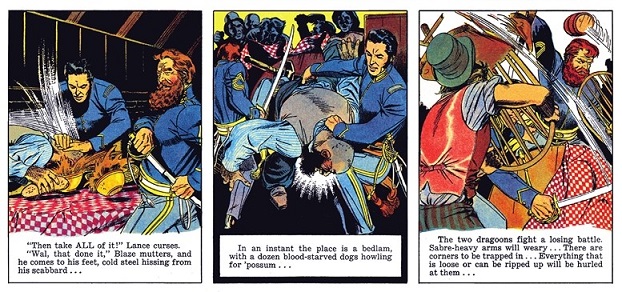

An interesting aspect of Lance is the theatrical movements, which we also find in Dan Barry’s Flash Gordon during the 1950s. This “ballet” of bodies in action, almost flying, in both these comic strips, fascinated me as a child. However, Tufts also possesses perhaps even more important ability, to depict the phenomenal calmness, relaxation or defeat, when the body and soul are at rest or powerless. Regardless of the theatricality of some of the physical conflicts in Lance, Tufts perfectly depicts human anatomy, as well as the dynamics of a body’s movement. This knowledge is expressed in exactly the opposite way from the mannered, not fully motivated dynamic anatomy in Burne Hogarth’s Tarzan. Hogarth fails to convey a convincing interpretation of the moment when he tries to capture the movements. Tufts’s energy was stronger than mere elegance, and he freed himself from the negative ballast of academicism. In the cathartic moments of adventure in Lance, Tufts was more than able to leave the static elegance and dive into dust.

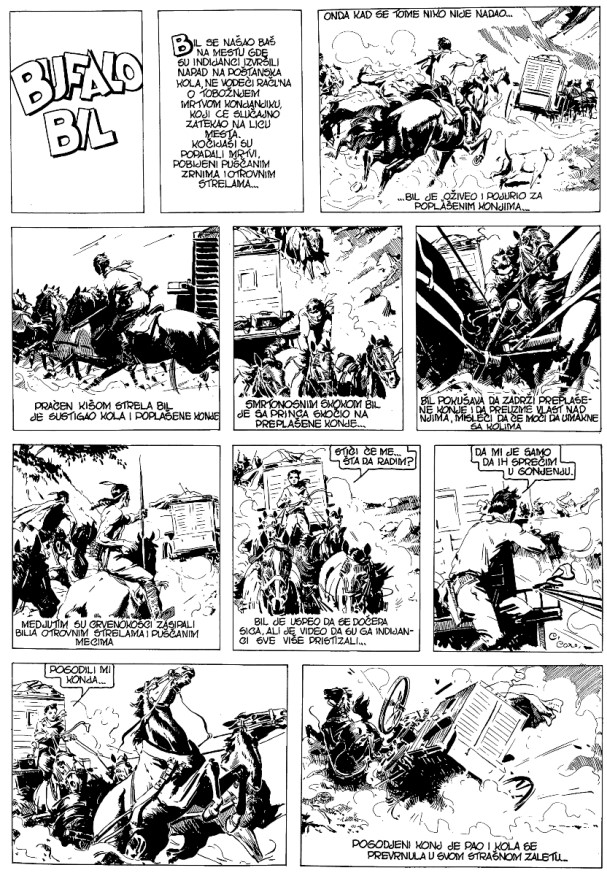

Obsessive attention to detail and historic graphical precision are, of course, not the same as opting for a particular visual style in comics. Hugo Pratt, François Bourgeon, Jacques Tardi, and Tufts share this obsession, but they choose to express it in very different artistic styles. If we continue zig-zagging through the history of comics, we encounter Sergej Solovjev (1901–1975) and his early Western Buffalo Bill (1939). This comic strip had much of the artistic elegance and poetic power that we see in Lance. In addition to the majestic drawings, the scripts by Branko Vidić contributed to this comic becoming an early masterpiece of the Western genre. Surprisingly, Solovjev, already in 1939, showed great power of reduction and abstraction in creating film-like comic scenes. Solovjev took an early, anticipatory step forward, like Pratt several decades later, broadening the possibilities of expression in comics.

About whiteness & the absence of word balloons

Comic strips follow a set of conventions. We abide to these conventions, so that we can read comic strips and enjoy the possibilities of an integral narration. However, when there is an absence of word balloons with dialogue, thoughts, and descriptive narration “inside” of the comic panels, when text and image are not “fully integrated,” some readers tend to assert that the feature is “less comics” in its nature. Today, when classical comic expression is challenged in experimental comics, questioning most of the comic dogmas, with the absence of word balloons in many comics (Lynda Barry, Seth) and the complete absence of text in some (Jason), casting a glance backwards and perceiving the lack of balloons in Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant and Tufts’s Lance as a shortcoming is a frivolous objection.

Without being aware of it, the reading of comics requires that we imagine the events of the gutter, the whiteness that separates the panels, or rather connects and integrates them. The gutter represents one of the basic presumptions of comic fluency in reading. There is a comics dogma of “hearing through word balloons.” Any reader of comics accepts it even without being aware of it. This is another basic presumption of comic fluency in reading. Not entirely opposite mental acrobatics is needed for reading text through captions — and they may include dialog — to push our imagination slightly further and hear the voices coming from the text below the pictures.

Beginning on December 9, 1956, Tufts began using word balloons in Lance, returning to his habit from Casey Ruggles. Was it an improvement? Not necessarily. There are certainly more important parameters to look at when evaluating the evolution of Lance, not related to the presence or absence of word balloons. In the first two years of Lance, Tufts did something that almost no one else would at that particular moment in comic strip history: He consciously abandoned word balloons to come closer to the grandiose epic type of narrative in Foster’s Prince Valiant. It clearly shows the extent of his ambition and courage. It’s thus useful to distinguish between the two types of decisions in Tufts’s work: the ones made under pressure of sales and distribution, and the authentic decisions originating from authorial beliefs and from the very core of Tufts’s creative process.

The restoration of a classic

Reprinting Lance in all its glory wouldn’t be possible without the pioneering work of Portuguese publisher Manuel Caldas, a tenacious digital restorer. Caldas came to prominence thanks to his complete restoration of Lance and black and white restorations of Foster’s Prince Valiant. He has also worked on restoring Casey Ruggles, The Cisco Kid, British Western Matt Marriott by Tony Weare and James Edgar, as well as a number of colorful classics, including The Kin-der-Kids by Lyonel Feininger and Krazy Kat by George Herriman. Besides Portuguese and Spanish editions, German publisher Bocola Verlag has published the complete Lance (2011–2013) in five volumes. There is also a Norwegian edition by Thule forlag (2013–2016) in four volumes (plus a deluxe edition in a single volume) and a Serbian edition (2015–2017) published by Makondo in four volumes. For several decades, I had been searching for quality reproductions of Tufts’s masterpiece, and after getting in contact with Caldas in 2013, I strongly recommended Lance to Makondo for publication. As a result, I also wrote the introductions for all of Makondo’s books.

Humor in Lance

In the early Lance adventures, Tufts’s work is characterized by the rudeness and carelessness of youth, insensitive to the “work of old injuries” at a mature age. Tufts purposefully introduces “a little bit of salt,” Münchhausen-like exaggerations revealing his talent for the grotesque. However, few authors possess an equal talent for humorous and realistic storytelling, but both Dan Barry and Tufts have included occasional comical elements and sequences in Flash Gordon, Casey Ruggles, and Lance. Foster’s attempts to produce humorous escapades in Prince Valiant have, on the other hand, always been lacking in spontaneity. While Barry devoted entire episodes of Flash Gordon to humor, with a notable affection for grotesque stylization, Tufts humorous escapades in Lance are fewer, the longest being two sequences with Big Felon, and a crazy scene in which we, in a cloud of dust, see three actors: a hen, a horse, and our hero’s legs. In the scenes featuring Big Felon, Tufts sympathetically captures the epic dimension of lying and exaggeration, in hunting stories blending facts with pure exaggerated fantasies. You get to know Felon by his incredible strength, his crazy courage, and his tendency to tell more than actually happened, but the boundaries between fact and fantasy are so subtle that Felon emerges as a highly sympathetic character.

Existential tones of the story

In Lance, we encounter narratives and themes which would not appear in films for decades, in works such as Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate, Arthur Penn’s Little Big Man or Ralph Nelson’s Soldier Blue, all films breaking new ground in the world of cinema, but dealing with topics Tufts began to explore in Casey Ruggles and Lance. Tufts, of course, did not create the anti-Western when he decided to tell the most beautiful Western epic ever and succeeded in his efforts. He didn’t know, however, that he was actually singing the swan song of the Western in the weekly newspaper comics.

Tufts is also a good at capturing the emotions of conflicts between his characters. The frenzy of their psychological interactions is linked to the physical action, and it extends far beyond the visual and narrative conventions used by Foster in his masterpiece, Prince Valiant. Of course, Lance is a melodrama, but melodramas differ from each other in their ambitions and some, like Lance, push their characterizations much deeper than the average reader of the genre will notice. One of the revelations of reading Lance is to understand that he is at a transition point, in between accepting the “scenic and genre conditionality” of the old classics, and the emotional layers he created that reach far beyond those same “rules and regulations” by subverting them.

While Tufts truly enjoys adventurous escapades, his narrative talent pushes him to include challenging topics which break with his genre’s conventions. Some of this revolting spirit is also found in the work of his role model, Hal Foster, but Tufts would take it much further. Tufts acts as a more radical psychologist in borderline situations than Foster, especially when he introduces more intense, female characters than are found in Prince Valiant. The reader of Lance is offered a much deeper and multilayered adventure, the kind we decades later find in the best graphic novels of today.

Interestingly enough, the less “masculine” the stories in Lance are, the more complex they become, and the tragic characters are generally stronger than those characterized by conventional male characteristics. Several episodes are dedicated to female characters, and some of these episodes are named after the protagonists (the episodes had titles when originally published), as was the case with the episode about Elizabeth Hackett.

The story of Elizabeth Hackett

Tufts gradually introduces more psychologically complex characters than you can find in the traditional good guy vs. bad guy Western. Hence, fans of the Western genre may at first not even notice the deeper tectonic changes in his narration. In the almost Chekhov-like story of Elizabeth Hackett (January 1, 1956), Tufts aims straight for the heart of his reader, with his blend of realistic and poetic elements. Focus gradually shifts from what is happening to the characters, to what is happening inside them. The emotional elements of the story are more important than the plot itself, and the story would be entirely Chekhovian if Eliza had ended up captured by her conflict of emotions, beyond ability to articulate them. Instead, her decision of apparent self-sacrifice is calm, mature, deeply rebellious, and probably unprecedented in the history of comics. A complex process of moral standards and personal convictions guide Elizabeth’s choices, challenging our definitions of sacrifice, our definition of freedom, and dealing with circumstances beyond our control. I have read this Tufts’s story several times over a span of several decades and still consider it one of the best stories I have ever read. Whenever I return to the story, its power does not weaken, only confirming and reinforcing the values it encapsulates.

You don’t have to always agree with Tufts’s views of the world, but you will never remain indifferent to his stories. In the history of comics, you will encounter great artists whose virtuosity will change your own view of the world. Tufts is one of those artists, who created stories which remain engraved in our memories due to their psychological depth, similar to the best episodes of Milton Caniff’s Terry and the Pirates.

The story of Elizabeth Hackett was first printed from January 1 to March 11, 1956 and poetically surpasses the average narrative quality in Lance. It is a poetic upheaval in what until then had been a somewhat masculine, even simplified narrative. This story was preceded by the appearance of three female characters, the Indian girl from the Sioux tribe, Melisse, the niece of colonel Dodge, and a small girl who has survived the massacre of her parents. These three characters introduced a softer tone into the adventures and opened a path for deeper narrative interventions. Even if Tufts had explicitly wanted to embark on an analysis of the characters of the Indian chief and Eliza, he would hardly have managed to tell such a radical story in 1956, when the ideological barriers between races in general were much more impenetrable. Instead, Tufts opted for a narrative perspective defined underway by a stream of consciousness, where, when he started it, he never knew where a story was going and how it would end. In this way, he was able to tell unique stories within the Western genre, an anticipation of daring narrative tones which would follow in comics decades later.

Narrative Meandering

(Psychology, genre, history and the language of comics)

Meander: a geographical term for a river that meanders gently through a landscape in the shape of the letter S. Meander can be a winding curve or bend of a river or road.

River curves

Tufts’s ambivalent, genuinely fascinating narrative meanders between the existential and the genre, with his watchful eye constantly fixed on his great influence: Hal Foster’s Prince Valiant. In October 1956, the Indian chief Broken Nose, head of the Kiowa-Comanche, rules the tribal council and leads 2,000 Comanche and Kiowa into combat, preparing to attack the American army. Broken Nose previously subjects Lance and his friend, Kit Carson, to a tribal torture, beating, and starvation. Lance’s motive to fight Broken Nose, however, is not primarily revenge. In his mind, the rationalization of the real soldier prevails without the consent of his superior, Colonel Dodge. Lance defeats Broken Nose not with anger but with military tactics. After a long absence, Lance is back in uniform, returning to his role as a soldier. After his defeat, we encounter a tremendous psychological and physical transformation of the powerful political leader Broken Nose, who after losing power, quickly turns into an ordinary old man. Politics and leadership are powerful opiates, and the use of every narcotic speeds up the aging process.

Getting in psychological density

The next meander is a story of the Indian girl called Many Robes falling in love with Lance. A story about a tragic type of hope. The desperate hope of a rejected person is one of the saddest moments in the development of a love affair. The pain of unrequited love or cessation of reciprocated love is authentically shown. The kind of pain that can serve as a trigger for sinking into obsessive love, where the boundary between falling in love, possessiveness, and the inability to accept failure and rejection is lost. Here, Tufts addresses the phenomenon that 20 years later would serve François Truffaut to direct The Story of Adèle H. (1975), which is about the tragic, obsessive love of the daughter of Victor Hugo (Adèle Hugo) for the British lieutenant, her former lover. It ends up with Adèle persecuting a lieutenant who no longer captures her emotions, then in self-destruction and insanity. Obsessive love has been the object of a series of breakthrough psychology books since the ‘90s. And Tufts was one of the first in the history of comics to touch on this topic – where the agony of separation between love and obsession begins.

The story is very short, only six condensed pages (December 2, 1956 – January 13, 1957, intercepted by one Christmas page). Previously, Tufts told a short, two-page romantic episode about Many Robes and Lance and its painful ending (May 6–13, 1956). As with the story of Elizabeth Hackett, which he concluded in 11 pages, Tufts proves himself to be a master of the short story. Chekhov’s poetics of short stories were once described by Thomas Mann as: “Genius can be bounded in a nutshell and yet embrace the whole fullness of life.” Tufts showed that this was also possible in the Western comic strip. Therefore, I claim that the greatest adventures of Tufts’s narrative mastery are found in such miniature psychological studies. Sometimes, these insightful glimpses are restricted to a single scene, or even a vignette, and then the comic panel becomes a nucleus of condensed energy of the comic language.

In Tufts’s hands, the story brims over into the visual and vice versa. Lance is an integral narration, only dressed in neo-classicist clothes. Even in his earliest pages, when he was using text under the panels, it did not change much. Tufts never describes the landscape with redundant words, and his language does not suffer from the kind of pleonasms which were later typical for French Western comics. You sometimes encounter it even in Blueberry (the visual masterpiece by Jean Giraud), thanks to its writer Jean-Michel Charlier, who ignored minimalism in words. In Lance, text and pictures are feeding each other in a healthy diet. Landscape and psychology go hand-in-hand, as well. The dynamics of Tufts visual sequences turn into condensed compositions of an astonishing beauty. Sometimes, it turns into a chiaroscuro vignette.

Time flow within Lance

The story of Lance spans 13 years, up until a year before the events in Casey Ruggles. This was an interesting inversion and an innovative process at the time. Tufts creates Lance as a prequel to Casey Ruggles. The word prequel was still unknown. According to The Oxford English Dictionary, it appeared in print for the first time in 1958. Only in the ‘70s did it come into widespread use. To make things more interesting, Tufts gave us a hint by adding Casey Ruggles as a minor character in Lance. Ruggles appeared very discreetly on August 1, 1957. We hear his name called during a meeting of volunteers. We can assume that it is Casey we see just below the balloon itself. Of course, he is somewhat younger than in the Casey Ruggles series, since this event occurs in 1837, 11 years before Casey “stepped into” his own narrative. Later, Casey gets a slightly more prominent role in Lance.

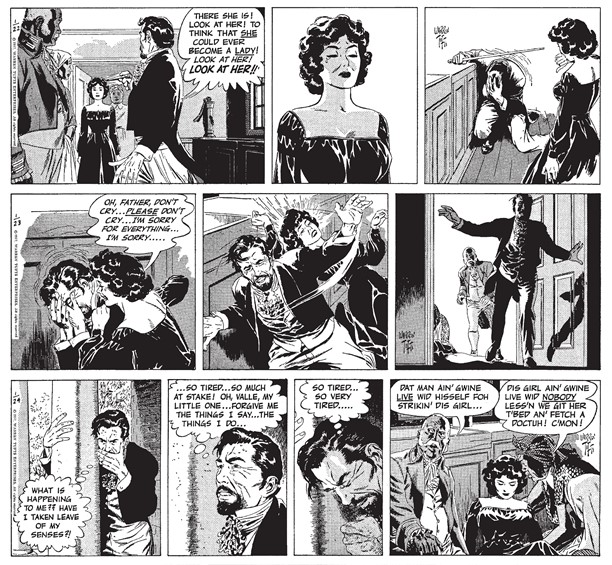

Black & white occurrence of Valle Dufrain

The first black and white daily in Lance is excellent. Brilliantly drawn, it brought a completely new narrative into the series, telling the story of Valle Dufrain and her father, André Dufrain, who are lost between business ambitions and wrongly articulated love and care for her child, and his business enemy, “Black Jack” Stanton. Over the next five months, Tufts opted for longer storytelling passages and introduced new characters, some of which would have a profound effect on future events. Tufts’s Western metamorphosed into a story of the unscrupulous aspects of accumulating wealth and the eradication of specific ways of life that are doomed to disappear due to economic pressure. Throughout the story of a dysfunctional family, Tufts managed to touch on the problem of the fragility of male psychology, where in the father unsuccessfully tried to articulate his role as a parent by confusing it with issues like honor.

The most striking villain in the story is certainly “Black Jack” Stanton. He embodies typical attributes of the brutality involved in the primitive accumulation of capital. That kind of brutality differs from the brutality of liberal and neo-liberal capitalism, in the sense that there is a much more personal connection between the entrepreneur and the victim. There are fewer intermediaries and corporate regulations. Stanton’s “helpers” heavily rely on physical violence in order to achieve his goals.

The loving sadism of a hunter hunting his prey

Stanton’s story is a study of the “loving” sadism of a hunter hunting his prey, and the prey is Valle Dufrain, the object of his desires. This is a story about the relationship between sexuality and economy, male domination of women, reduced to openly traded goods, including the calculations of Valle’s own father.

Due to the dialect and jargon of an uneducated black woman, a servant of the Dufrain family, one’s first thought might be that Tufts is a slave of racial stereotypes. Tufts, however, guides us into the traumatic dysfunctionality of the relationship between father and daughter. An uneducated black woman is able to see what Valle’s father is incapable of seeing, and Tufts’s interest in drama exceeds the racial stereotype that served as a standardized formula of the genre of that time.

After several months of this tour de force and dailies of impressive beauty, Tufts continues with nicely drawn daily strips, though no longer delivering daily masterpieces, as this, in the long run, would have killed him. The creator needs to be able to survive, creatively and health-wise during the full duration of the series.

Incidental adventures on the road: saber & the tank

Following his role model in Prince Valiant, Tufts also takes on some narrative motives that Foster brought to his firmly established pattern. Bandits on the road intercept Lance on March 10, 1957 (and before that as a young lieutenant in his battles with Indians on June 19, 1955 and November 11, 1956). Of course, the attackers will regret their intent, and the encounter serves Lance only as a fitness exercise: “Like coiled spring steel cut loose, he charges!” Fighting is more of an amusement; violence is sedated through choreographed action. Men’s sport.

On the previous Christmas Sunday (December 23, 1956), we find a strange occurrence involving Tufts’s contemporaneity of the times — a tank. In hindsight, viewing this as a possible a mistake, Tufts would not engage in such meta-narrative temporal digressions into the present again.

Moralists of classical views

After years of fur trading and the dramatic abduction of Valle Dufrain, the narrative in Lance goes into lighter, more subtle tones. Tufts succeeds with an uneven success. Nevertheless, his narrative portraits of female characters go deep, and they should even be considered radical. His idea of clearly divided male and female roles persist.

Back to the western genre

After moving from action to psychological drama, the narrative pendulum moves towards the intimacy between Lance and Valle in which Tufts tries to capture the charm and lightness of true romance. After these romantic interludes, it’s time again for a U-turn from pre-marital anecdotes to action, back to the West. Tufts is a master of putting you comfortably into the seat of his narrative vehicle. Then he steps on the gas and starts twisting along “winding roads” to mesmerize you by changing the landscapes you observe.

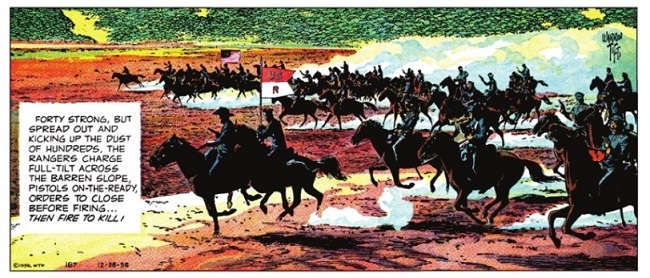

And Tufts begins to embark on a new plot: “Meanwhile, in the heart of the Rocky Mountain fur country, another incident takes place that is to have important bearing ...” (July 9, 1957) “Three incidents, all fitting the one mold cast by history!” (July 12, 1957). A rangers’ regiment is created, a complementary field service to assist the colonization of the West by white men. The men of this light cavalry, selected from the 1st Dragon Regiment, form a new, inexperienced unit, and Lance advances as an incompetent lieutenant to colonel to lead them. This unit also has a secret mission, as Lance receives instructions to read, memorize, and burn.

The existential & genre perspective

This aspect of Lance’s adventures can be read either from the existential perspective of the future genocide of the American Indians, or from the genre perspective of the American epic conquest of the Wild West. In Lance’s inner structure, some existential cracks in the genre appear. Part of its genre ambiguity is that there are so many of them. History breaks through those cracks. The Indian Blackfoot tribe will not only be threatened by extermination by military means, but hunger and infectious diseases, primarily cholera and pox. In 1837, ferry passengers of the American Fur Company were infected with the pox and 6,000 Blackfoot would die as well.

From another planet

Women play a special role in Tufts’s stories. Often put in borderline situations where their personalities emerge full force; a powerful transformation.

The challenges women face in Lance through circumstances beyond their control cause them to abandon then standard social roles. Their strong individualities surpass their environment, and women appear as if being from another dimension, “from another planet.”

Dan Barry in Flash Gordon also used this portrait model in the second half of the ‘50s, the same period Tufts was working on Lance. It was much less unexpected in Flash Gordon because Barry was operating within science fiction conventions that provided him with an “excuse” for estrangement.

It worked just as well in Lance by causing the defamiliarization in the Western genre.

The episode with the “White Indian” girl (September 25 – November 9, 1957) is one of the most remarkable examples. “The Story of Elizabeth Hackett” also fits perfectly into the idea of women abandoning their standard social roles. Valle Dufrain, the future wife of Lance, shows this rebellious spirit, as well.

Is love stronger than anything? No. But it’s able, like a flower that grows from cracks in the sidewalk, to emerge in the most desperate of conditions. In Lance, Tufts frequently deals with extreme situations and human psychology.

Love, more precisely falling in love, is one example, a strong romantic impulse that triggers the story, a trigger headed straight toward melodrama. It’s interesting how Tufts narrates the episode when a young, almost boyish soldier falls in love with the “White Indian” girl and helps her escape. On one side, Lance’s initial attitude is one of explanations and rationalizations. It’s a colonel’s jargon which confronts every situation with the question of “what constitutes a danger to the mission,” and in this story there’s certainly true disobedience by his subordinates.

The second voice in Lance emerges slowly, the voice of a sensible man who knows that the beginnings of love cannot be easily stopped by rational arguments, commands, or prohibitions. That’s why at the end he states to Colonel Blaze, “You tried to interfere with love, that’s all,” and grins. “You didn’t have a chance to start with …” (November 9, 1957).

Body language as a dynamic theatrical device

You can also see Dan Barry’s influence on Lance in terms of Tufts’s visual expression, starting from the last years of Casey Ruggles, especially in scenes in which Casey “hovers” over the abyss; Barry’s favorite theatrical device.

A stylistic affectation occurs when he thrusts Flash into states of flight, diving, and levitation — a variety of situations that are an excuse for visual extravagance. This extravagance became part of the visual poetics of Barry’s Flash Gordon.

The theatrical method described above is not related only to the medium of theater. The comic strip was a kind of front runner. In the theater, this type of effect became technically efficient and poetically convincing in practice a decade later, first in the theater of movement or physical theater, where the storytelling takes place primarily through physical movements, total theater, and the fascinating choreographies by an experimental theater stage director, Robert Wilson, in the last four decades.

In film, however, this kind of effect, primarily based on slow motion, was developed at the very beginnings of the 20th century. Poetically, it was successfully used by Russian film director Vsevolod Pudovkin in The Deserter (1933) and even more prominent in Leni Riefenstahl’s documentary film Olympia (1938). Riefenstahl used slow-motion recording, camera on rails, underwater images of the jumper in the water, the extreme corners of the camera — all to capture and impressively interpret the choreography of the athletes’ body movements (glorifying the Aryan national socialistic body ideal). Nobody, however, will challenge her abilities as an authentic innovator of film techniques and her high aesthetic quality.

This melodramatic frame is perfect for displaying the irrationality of human interaction, which largely depends on circumstances weakening our ability of tolerance. This is the setting for Lance’s rangers facing the cruelty of winter and trying to help snowed in settlers, condemned to death by hunger and the harshness of winter.

Of course, the melodramatic crown in the story is the salvation of saving a baby. Dying parents entrust Lance with the baby as a pledge of life that should remain after their passing.

Commanded by Lance, the rangers' task is to make maps, but the army never stays busy only with cartography; they hunt, they keep the peace, and along the way, they kill an Indian or two. Ultimately, it is just a short social-political interlude for a new melodrama to take off. Lance becomes a victim of his own imagination, suffers from jealousy that makes him suddenly return to his wife, Valle. This part of the story is the weakest and the least convincing. Tufts is a much better and less conventional psychologist in extreme situations.

Problems with narrative rhythm & format in Lance

The story of Valle’s blindness (January 6 – January 30, 1958) begins abruptly, like in real life. The entire station that Lance entrusted her to oversee is infected with a mysterious fatal disease. Because of the disease, thousands of months of dreams and hard work go up in smoke.

The station is burned to prevent the spread of the disease. Valle gets sick. She survives but goes blind. Tufts’s first wife, who suffered from multiple sclerosis, — for which there was even less of a cure then — has some echo in this story that changes Lance and Valle’s perspective on life.

Tufts told the story of Valle’s illness in a bit of a rush. There was an inversion of the order between the Sunday page of January 26, 1958 and the daily strips that followed, which are much more powerful than the ending of the Sunday page. It causes the Sunday page to look as an early narrative gesture. This kind of narrative rush in Sunday pages created a certain sense of repetitiveness. When the nuanced interpretation appears after an event’s occurrence, it somewhat weakens the narrative tension.

Obviously, the Sunday pages were real narrative axes, and Tufts did not want the dailies to precede in dramatic storytelling. However, sometimes this was indeed a weakening factor in Tufts’s story structure.

On February 15, 1958, the last daily strip appeared. Tufts’s reason was work overload. Structurally, it was a change for the better. Narration improved because the two narrative rhythms were not mutually consistent, especially in the last few months of the daily strip’s run. Some of the narrative weaknesses, however, remained. Often, in the last panel of the Sunday page, we encountered something that should be surprising but was told in a flat tone that weakened the surprise. However, in terms of visual narration and in spite of the slightly less detailed work, Lance retained its graphic and color greatness.

Word balloons were introduced in Lance on December 9, 1956. The black and white daily strips started on January 14, 1957. They lasted until February 15, 1958. All of these changes back and forth, done with the best of intentions, did not help Tufts to improve the sales or later to regain and regularly maintain a good narrative rhythm. Each narrative format requires finding your own voice, and combining different formats may appear slippery.

A tour de force in melodrama

Since 1957, Tufts had been working on his melodramatic tour de force in Lance, demonstrating his mastery at reaching the heights of drama in a continuous narrative flow.

From the incredible love that is born between the young soldier and the “White Indian” girl, through the story of death in the winter cold, the death of hunger and the baby that becomes a symbol of hope for survival. Through the miraculous story of Valle’s blindness and her even more miraculous healing. Through the story of an aggressive bulldog, Senator Hart, to the Mexican ending, which is an ideal melodramatic décor for great unrequited passion.

After Tufts emulated Foster’s structure of marital life from Prince Valiant, Lance was a faithful and dedicated husband with no strays into irrational passions. He is only an observer, an object of passions by others, whether the love of a “hellish” father’s matchmaking is in question, and the woman who falls in love with him must, of course, fail or end tragically.

The impressive scene (last panel November 2, 1958) of Maria de Castro’s death is not only theatrical, but it seems as if it literally is taking place on stage. Actors surround Maria, and a choir of witnesses similar to a Greek tragedy ends the drama. Reading this comic in all its genre modes, including its weaknesses, makes Tufts’s efforts more human.

Characters and author

There is something romantic, hearty, and passionate beyond the limits of caution and frustration in many of Tufts’s stories, both in Casey Ruggles and Lance. Some of these attributes seem to reflect the personality of the author himself.

In his work, Tufts did not approach the challenging, very adult and disturbing topics such as torture, rape, violence, drug trafficking, and corruption in politics, incest, and racism in any particularly strategic way. He was interested in ethical situations that take into account the context of the behavior of the participants involved rather than judging them according to absolute moral standards.

According to this rather existential point of view, in addition to universal laws, each situation imposes its own circumstances, instinctive decisions, and laws of love that cannot be reduced to rationality. Hence, Tufts was making an occasional radical diversion into psychology, although in an epic and often melodramatic way. He was also able to portray racial divide and discrimination years before the struggle for civil rights. In his own words, Tufts never knew how his stories would end. They were the result of a “stream of subconscious.” He was observing the thoughts and actions of his characters to events in a constant flow.

One of the consequences of this type of narrative process is that some of his motives, after he introduced them, were not yet fully developed. Some great stories with powerful potential were too quickly resolved, and Tufts could have developed them further. However, Tufts’s narrative frame was not the model for today’s graphic novel but a of a comic strip with an epic flow.

In Tufts’s major series, we find tragic characters, perhaps best exemplified by Lilli Lafitte in Casey Ruggles and the Indian girl, Many Robes, in Lance. In both cases, it is a tragic love, unresolved love, impossible to be fully fulfilled that sinks into obsession. The melodramatic aspects of narration can be found in the final years of Lance in abundance, although always merging with the adventure. Tufts had a strong inclination towards this combination of genres. On the other hand, gentle humor or ironic tones fitted his narrative style better than trying to create a straightaway humorous passages, or satire, which would bring him closer to some stiffness and insufficient spontaneity.

Valle

Tufts created Valle as a character with warmth, much sweeter than Foster’s Aleta in Prince Valiant. What is the difference between these two remarkable women? In Aleta, you can detect some tiny layer of an “ideologist” in practicing her beliefs. Valle speaks only in her own name, and she does not have a confident position of “it should be this way.” In spite of all Tufts’s melodramatic “setups,” Valle never just shows an affectation. Her full-hearted, discretion, sometimes discouragement, emanates from the depth of her character, never from a learned social stand. In Valle, Tufts created a genuine, authentic character. It was absolutely impossible for him not to bring her back, in his final farewell for Lance, in the last scene at the end of the series.

Moving from opposite ends of comic expressiveness

Tufts wanted to combine both directions of comic expression. On the one hand, he created open spaces and spectacular landscapes, including the grandiosity of the Rocky Mountains, and he found interesting camera angles and fluid motion that made dynamic sequences.

To unite both of these aspects — the static and the dynamic — was not an easy task to achieve in a comic strip that was meticulously detailed and done in full color. There is a division among critics which one is better: Casey Ruggles or Lance.

Some prefer Casey Ruggles, finding it less academic, less “perfect,” younger, more thrilling, and fresher in exploring the possibilities of the Western genre. In Casey Ruggles, word balloons were used instead of placing the text in the caption boxes below the image. However, as I mentioned earlier, Lance used Foster’s Prince Valiant as its role model, which in the eyes of many critics emphasized the separation between text and picture. Other critics find Lance a more mature work in which the historical period is well defined, the landscapes are impressive, and color experimentation is brought to perfection. Henry Yeo, in his Warren Tufts Retrospective (1980), opts for Casey Ruggles. My preferences go toward Lance, although, at the end, I see this as a false dilemma. Tufts created diptychs — two complementary masterpieces. Together, they reveal the full range of Tufts’s storytelling talents. Both reached the very peak of the genre, as well as explored the infinite possibilities of the medium of the comic strip, coming from opposite ends of the genre’s expressiveness.

The end of an era

With passionate perfectionism and a willingness to engage in the creative process, Tufts seems to have created a similar trap he had previously faced with Casey Ruggles. The intensity of the creative effort of the artist needs some protective mechanism built in to survive, cope, and continue the long run. If great talent and great work are followed by big dreams, this protective mechanism is often lost along the way.

Somewhat blindly, Tufts hoped that Lance would not experience the same fate as with Casey Ruggles — the failure of securing a film adaptation. He went so far as to imagine himself in the leading role. Regardless of the apparent similarity between the author and his hero (Tufts made Lance almost a self-portrait), as well as the attractiveness of Tufts’s appearance and his experience in acting, this still seems a farfetched idea that would face a whole host of obstacles. Nothing, however, happened. The era of the Sunday comic page was over. Lance was a swan song of this comic form.

Don’t look back

The whole of Tufts’s life was moved through cycles: a passionate dedication to everything he did. He constantly devoted himself entirely in the creative process. Such was his work on the radio, where he showed multi-dimensional talents on Lance, on self-distribution of his own comic strips, and his full commitment to piloting and building his own aircraft. Only the sky was the limit.

There were two phases in these creative cycles: a complete dedication and then departure.

He was not a person who looked back or was ever returned. Especially if his Achilles heel caused his creative enthusiasm to turn into complete exhaustion, bitterness, and disappointment over the confrontation with the boundaries his hopes and expectations met. Tufts had a specific type of pride and respect for utmost quality of the things that he was committed to.

The circumstance of the comic strip’s sales was the independent distribution that Tufts’s father and brother took care of. Instead of the leading U.S. daily newspapers, they managed to reach a lot of local small-town papers. Overall circulation failed to outperform Casey Ruggles, which was certainly the ambition.

A series of bad strategic decisions during the evolution of the series, made with the desire to financially improve things, only complicated matters and further increased the work pressure on Tufts. The introduction of a daily strip did not improve sales. It complicated the creative process because it was necessary to synchronize both Sunday and daily story lines. In the final period, Tufts had to abolish the daily strip again. The tastes of the era were changing. There was no interest in making a film of Lance, even though Tufts was in full creative control.

When Dennis Wilcutt interviewed Tufts in 1979, less than three years before his death, and asked if he would ever return to the comic strip, he resolutely and calmly said no. He was not the kind of person who would return to passions he had left behind.

The sky’s the limit

Did Tufts’s gigantic effort on Casey Ruggles and Lance get the respect it deserved? In the league of enduring devotees to his artistic achievement, there are readers who, after many decades, can recall in detail powerful moments of his story lines. Both Tufts’s strips lasted five years. Both became too labor-intensive and did not meet financial expectations. On May 29, 1960, the last Lance Sunday page appeared. Tufts left the comics field and primarily worked for television, doing some voice acting and working as a storyboard artist.

The ultimate creative cycle of Tufts’s passions is nevertheless the greatest adventure of all. He learned to pilot, was actively engaged in flying small planes, and decided to construct his own. He died on July 6, 1982, at the age of 66, piloting Thunderhawk, a small open-air double-leaf of his own design. Tufts himself, the great narrator, could not have imagined a better ending to the story of his own life.

A version of this piece appeared in Warren Tufts' LANCE, Classic Comics Press 2018.