Adieu, Ligne Claire

Let's not bury the lead: Claire Bretécher, who has just died at the age of 79, made both real and important comics history. The fact of her sex isn't irrelevant. But it wasn't being a woman that made Bretécher one of the few (if not the only) artists to work for all three of the 9th art's founding journals: Tintin, Spirou and René Goscinny's Pilote. Being a woman wasn't why, with Marcel Gotlib and Nikita Mandryka, she founded BD's first adult journal, L'Echo des Savanes. It wasn't why her success with Les Frustrés helped get comics out of the children's page in papers.

Well aware of that power held by editors, Bretécher self-published her first 25 books. Unheard of at the time, this did more than keep her independence and inspire others. It also, as she pointed out, "made me a lot of money".

All this was due not to Bretécher's sex but her talent. For she modernized, in BD terms, a venerable genre – the comedy of manners. Using her own milieu as material, she proved as acerbic as Marcel Proust (or his 18th-century idol the Duc de Saint-Simon, a serial killer of belles lettres). For Anglophones, a good comparison is Noel Coward at his drollest. But Bretécher also owed a debt to French caricature – more than to those comics which, when she began, were still called "les illustrés".

Both in terms of graphic style and humor, what she gave comics was totally, truly original.

It got going during the mid-1970s. In 1973, for an "ecological monthly" called Le Sauvage, Bretécher created the strip Les amours écologiques du Bolot occidental ("The Ecological Loves of an Occidental Mutt"). This was the story of a libidinous hound who runs riot in a home for endangered species. Its topical gags attracted editor Jean Daniel, who ran the left-wing weekly Le Nouvel Observateur. In September of 1973, Daniel gave Bretécher a weekly page in the paper, so she could "poke fun at us and our readers".

Using the rubric La Page des frustrés ("A Page for the Frustrated"), Bretécher installed an aquarium of angst. Its denizens were the tribes thrown up by changing times: hippies, yuppies, punks, ecologists and bobos ("bourgeois bohemians"). The way she drew them was as new as they were and the series became an immediate hit. Soon, both L'Obs and its rivals were hiring more cartoonists.

One big fan of Les Frustrés was Kim Thompson. Here, from 1978, is his summary of it: "Claire Bretécher is… probably the best cartoonist now working in France… Although she has been compared to Garry Trudeau – and it is, in a sense, a fair analogy – her drawing and his are at opposite poles. His is carefully rendered and graceless, hers expressionistic and vivid. It is partly inspired by such American cartoonists as Johnny Hart and Brant Parker, whose work she greatly admires, and displays the same appealing mixture of superficial looseness in rendering and tightly-controlled effectiveness. All of them know precisely which elements can be dismissed with an offhand doodle… and which must be delineated with precision. Yet Bretécher's bizarre faces can convey any feeling or any mixture of feelings and her expertise at using a minimum of background to situate the strips perfectly is evident throughout.".

Les Frustrés drew a bead on middle-class self-righteousness with all its ironies. Its characters militate for sufferers all around the world while they ignore or snub hapless locals. Another of its subtexts is social life as investment – the view that every connection has to imply reciprocal gain. The strip is all about power in human relations. But its biggest laughs come from topical follies and hypocrisies. Jean Daniel wrote that he had unknowingly planted a bomb in his office: "Claire captured our all our tics, mocked our every neurosis… while laying bare our most secret accommodations."

Born in Nantes in 1940, Bretécher hailed from the bourgeoisie she mocked. Her father was a lawyer, her mother a "submissive" housewife – but her mother stressed that Claire should work to earn a living. It was a Catholic family, she once said, "dominated by women, in which all the men were cretins". Yet she had no complex about her roots. "I'm a typical instance of the category I draw: the educated, liberated, left-wing bourgeois. People whose conduct can contradict the views they hold."

By the mid-70s, Bretécher was a media star. She was filmed, recorded, featured on magazine covers. Critics compared her work to Balzac's Human Comedy and intellectuals paid her compliments so they would look au courant. In 1976, Roland Barthes caused an uproar by declaring her "the year's best sociologist". Other academic stars – Umberto Eco, Pierre Bourdieu, Daniel Arasse – followed his lead.

Watching old interviews about all this is startling and not just on account of all the vintage threads. It's because you're back in an era which mostly still sees comics as childish rubbish. Bretécher is not really there to discuss her work and she's not presented as an artist. She's on camera because her satire stung and – perhaps more importantly – because of her looks. This is where being female made a difference: the era's media loved her pixie hair and Bardot lips. She looks right out of a New Wave film by François Truffaut.

This wins her little sympathy, however, especially from female journalists. These young trendies, many of them dressed like her, can get aggressive. Why will she not call herself a feminist? they hector. "How can you indulge in such mockery," one of them frowns, "When, after all, you look the way you do?"

Bretécher, then in her 30s, gives as good as she gets. "Just what do I look like?" she shoots back. "The body you have doesn't count, what counts is how you feel. When it comes to me, well, I've always felt hideous, pitiful… barely even civilized. Maybe it's a little better now that I'm older. But when I was 26 or 27, it poisoned my life. Whenever some guy tried to pay me a compliment I would think he was making me into a joke. I'd respond aggressively and he would think 'What a bitch!'. What all that depends on is your frame of mind, and what creates that? It's created by Elle, by Marie Claire, by all those shitty papers and magazines! Publications that, instead of telling girls 'Make the best of what you've got, you too are beautiful', want them to spend eight thousand francs on some charlatan who sticks needles into their thighs to fight their cellulite!…. I'd like to have their hides, the women that write those articles!"

Bretécher is as independent as she is feisty. "At the moment, feminism is all that interests me. But it's a difficult thing because I've always hated militants. The people who are sure they're right, who think they're the only ones equipped to right the wrongs… It's they who embody the wrong and that's the end of the story. As an attitude, that drives me crazy. But, equally, as a 'feminist' you're obliged to play the martyr. Any subject is reduced to the fact you're being kept from becoming this or stopped from that..It just pisses me off."

There's a reason for the youthful Bretécher's tone of voice – her ultra-frank, direct responses and impertinent slang. They come from all those formative years spent in the ultra-male world of early French BD. Her trajectory was a singular one, unlike that of almost any other artist.

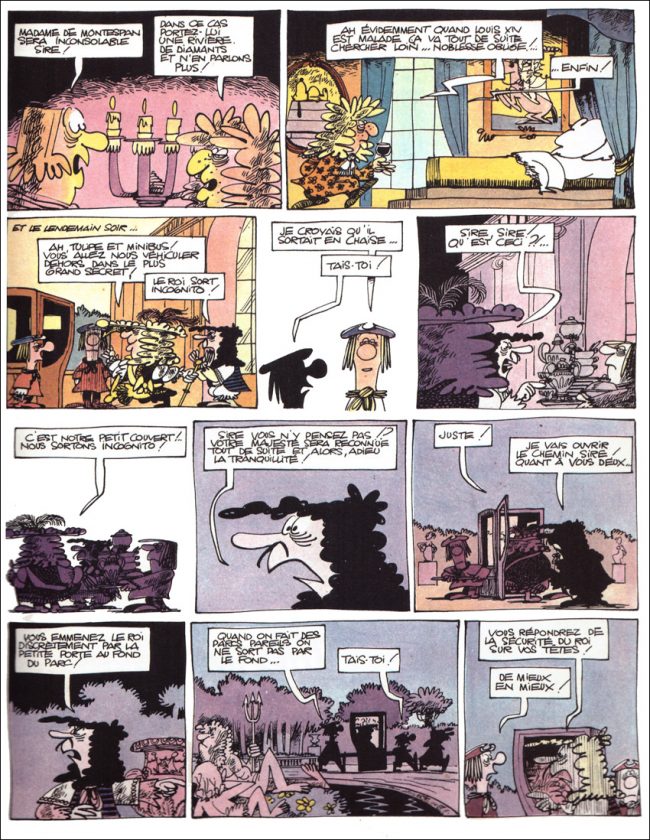

First frame of "X-Ray of the French Man", collection Inédits (Dargaud) © Claire Bretécher/Dargaud

The rebel in a Catholic family, Bretécher saw drawing as "my ticket out". After two years at the Beaux-Arts in Nantes, she briefly taught in a lycée. But, by 1960, she had made it to Paris. There she freelanced cartoons to magazines like Ici Paris as well as doing illustration for the Catholic Bayard Presse. "If I'd had the means, I would have tried to be a painter; I started drawing BD because they paid you quickly. Still, I've never thought of painting as 'better' than comics."

She was determined, worked enormously hard and was relentless when it came to cornering editors. Before the actual meetings, though, nerves could make her vomit. That was the case in 1963, before a one-on-one with Pilote's René Goscinny. Not yet a celebrity, Goscinny was already known for sponsoring talent.

Nor did he disappoint. The editor proposed she illustrate one of his projects, Les Aventures du Facteur Rhésus. This was a sequence of captioned pictures – a pun-stuffed story about a luckless postman. Because she couldn't really draw streetscapes or buildings, Bretécher soon found herself at a loss. The most basic skill required by les illustrés was drawing to order, visualizing scripts someone else had written. This was entirely foreign to the 23 year-old.

Her drawings were accepted. But "Goscinny made it very clear they were nothing special. He told me to come back when I'd learned my trade. He didn't spare my blushes but he was very courteous." Later, however, she was mortified to hear he "had told everyone I was really dirty and smelly. Although, at the time, that was actually true… I was always living in some terrible squat."

Bretécher would never forget her early struggles – and she never left Montmartre, the quartier where she lived them. "For years and years, I was always broke. People now hold that era up as a golden age. But, believe me, it was atrocious! Women were always needing abortions.…and finding somewhere to live was a nightmare."

By the much-vaunted heyday of May '68, Bretécher had made her way out of penury. "By then, thanks to Spirou, I had steady work so the demonstrations didn't interest me. They were just for those who had spare time, who could afford it." Real female liberation, she maintained, came in two forms: 1967's La loi Neuwirth, enabling legal contraception and 1975's La loi Veil, which legalized abortion. All her life Bretécher remained outspoken on the subjects. "Falling pregnant without wanting to," she said in 1998, was "as bad as having a cancer."

Between 1965 and 1966, Bretécher had illustrated gags for Tintin. But, when some of Spirou's Belgian stars were on a visit to Paris, she managed to meet them. She followed this up by sending them Des navets dans le cosmos ("Turnips in Space") and, soon, the magazine accepted a series: Les GnanGnan. (It featured babies having adult conversations.) "All that was critical," she told José-Louis Bocquet in 2007. "Because that was how I got to know Yvan Delporte, Jijé and Franquin. This was 1967 and it put me over the moon; Spirou was a totally mythic magazine."

By 1969, she was also back at Pilote. This time, she came prepared – with a medieval strip starring the princess "Cellulite". By now, Pilote's contributors included the press cartoonists Fred, Cabu and (Jean-Marc) Reiser. Goscinny had taken them in after the censor closed Hara-Kiri. Later, they would go on to form Charlie Hedbo.

All of them had an effect on Bretécher. But, at 29, she finally knew who she was and what she wanted. "I've made many friends inside the world of comics. But, in terms of art, the Belgians had the most effect – Delporte, Gillain ("Jijé") and Franquin. Franquin especially; he could make a straight line magic! All those artists worked like total maniacs. Uderzo and Goscinny too – although, of course, they weren't Belgian. Uderzo actually produced a planche a day! But Franquin… he might sketch a pig three hundred times before, in the end, he had something that satisfied him. He was fascinating, both as a man and an artist."

When asked about being "the only woman" in comics, Bretécher always drew attention to other names: Nicole Claveloux, Chantal Montellier, Florence Cestac, Annie Goetzinger and Jeanne Puchol. Her voice was never that of an embattled aspirant but the voice of a genuine equal to men. She trained, learned, worked and succeeded in a male environment.

Launching L'Echo des Savanes in 1972 proved to be another pivotal move. "Our self-publishing that was a revelation… after that, I knew how to do my books." Unlike Gotlib and Mandryka, however, Bretécher would have preferred to also work for Pilote. (The magazine's 1968 "uprising" – partly behind Savanes – had preceded her 1969 arrival.) "I never thought Goscinny would take L'Echo so personally," she told Bocquet. "It was just that moment in time… His success with Asterix turned him into a scapegoat."*

By 1973, Bretécher left L'Echo for Le Nouvel Observateur. There, from its start, Les Frustrés took off. "L'Obs didn't have the rights to make those strips into albums. But I didn't trust the big publishers either. I could never stand that kind of paternalism." Instead, she found a German printer based in Barcelona – and she began to bring out her albums. This adventure would last three decades and one of those who admired her for it was Goscinny.

Such independence, however, had a price. Bretécher's art – like her story – isn't really obscure. But it deserves much better. Most of her real inheritors, artists such as Catherine Meurisse, only happened across her work belatedly. Yet her influence permeates modern BD. Says Meurisse, "I was 25 when I discovered her, and I was stunned. She was so deeply feminist she needed no word for it and, right away, I recognized her insolence, her indolence and her brand of shrewdness. What she created had passed into our subconscious; it had become subliminal."

In 1982, Bretécher received a Grand Prix d'Honneur from Angoulême – an award that celebrated ten years of the Festival. This has been represented as a kind of second best. But, insists its current President, Stéphane Beaujean, the truth is much different. "To create that special award, they also created a special jury. So Claire wasn't chosen by the usual set of journalists, specialists and professors. She was picked by André Franquin, Fred, René Pellos, Jean Giraud, Paul Gillon and Bob de Moor – and de Moor was representing Hergé." Bretécher, he adds, was preferred over Jacques Tardi and Jean-Claude Forest.

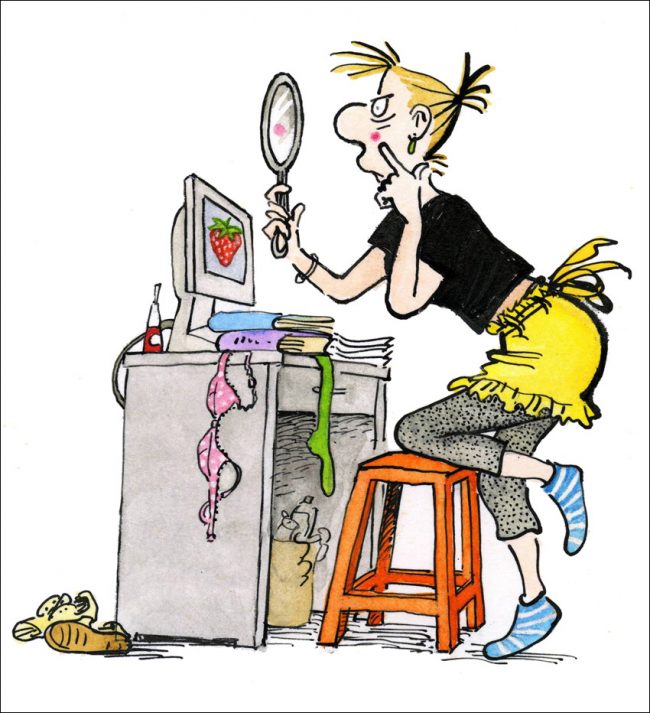

Bretécher was delighted – "I had been told I was as sterile as a stone", she told Libé in 1998 – and the new life energized her work. Her 1985 Doctor Ventouse, Bobologue was a delicious burlesque of medical snobs. But it was 1988 when she hit the height of her fame, with the anti-heroine called Agrippine. Now the artist's best-known character, Agrippine is a harebrained, exasperating teen. Between 1988 and 2009, over eight hit albums, Bretécher's portrayals of her changed the codes for cartooning adolescents. Her teens even spoke their own dialect. These dialogues, half overheard and half made up, were by Bretécher's invention. Yet now they seem uncanny – a preview of our texto-speak.

Bretécher published her last book in 2009. As time passed, she painted more, read more and travelled more alongside Carcassonne – who was often solicited for work abroad. Her studio remained in the family home, the single apartment atop an old parking garage. But, as comic blogs and web comics blossomed around her, Bretécher's importance became even clearer. During the early and mid-2000s, her shadow towered behind a whole cult of 'girly' cartooning. Charlie Hebdo ran two of her most worthy inheritors: La Vie Secrète des Jeunes ("Secret Lives of the Young" by Riad Sattouf) and Scènes de la Vie Hormonale ("Life with Hormones" by Catherine Meurisse). Libération had Aude Picault's L'air du rien – and, as time has passed, there have been many more.

But almost all of them are softer, rounder and, essentially, gentler. In a world filled with Smileys and "Likes", there is now a bit less room, a bit less taste, for truths that bite.

In May of 2013, the Carcassonne family went on a trip to Russia. There, on a Sunday night, 62-year-old Guy died of a brain hemorrhage. His burial in Paris' Montmartre Cemetery briefly reunited the shrinking world of BD greats. Two years later came the murders at Charlie Hebdo, followed by the mass killings in November 2105. Five days after those, the tribute Claire Bretécher opened at the Pompidou Centre. The artist herself attended only its private opening. Yet, at the time she died, Bretécher was negotiating a major retrospective.

In one sense, that is already going on. The last week has been a deluge of posts, front pages, web tributes – even graffiti in the streets. Bédéistes have hailed Bretécher as the "Queen of Comics" (Catel), "a rock star" (Penelope Bagieu) and "Notre-Dame-de-la-BD" (Blutch). Said Fred Lassagne (better known as Terreur Graphique), "Bretécher was unique. Not only was she great – she was maybe the greatest. There was a genuine science behind those lines. You won't find a single false note."

Almost every tribute profited from Roland Barthes' old quote, the one that called her a "sociologist". Back in the 70s, it was Barthes who benefited – from Bretécher's modishness and maverick status. A few years back, she was asked about his inescapable tag. Pale and elegant, Bretécher pursed her lips. "I've never really known what to say about that remark. Because, whatever I do, it's not actually observation. It's much more like assembling an arsenal…" She paused, then looked up with a glint in her eye. "But Barthes was well punished for saying that. Not long afterwards, he died!"

- Dargaud, Bretécher's publisher since 2006 have re-published all her classics

* La Revolution Pilote by Eric Aeschimann and Nicoby (Dargaud) is a guide, in BD form, to the magazine's characters and the upheaval that took place there during 1968