It could be said that in the past twenty-five years, North American comics artists have rediscovered their history. Century-old newspaper strips have been reclaimed and reprinted, dime-store works of passion unearthed and finally aired, styles revived and refined and reworked. And yet, for the most part this renaissance of rediscovery has only gone as far back as the early newspaper strips, only hesitantly reaching beyond the clearly-defined realm of Ben-Day and word balloons, and generally not embracing anything as far removed or as esoteric as surrealist collage or Victorian-era illustration.

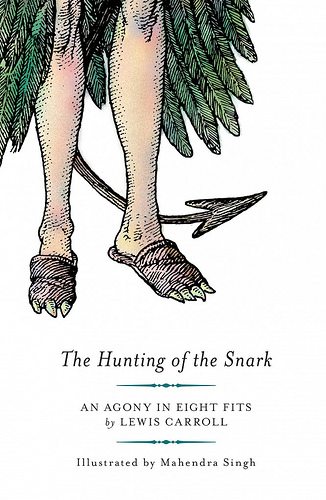

The work of Mahendra Singh, and in particular, last year's Hunting of the Snark, stands in proud defiance to this trend, daring to look back further in time, and further afield, embracing and emulating such disparate traditions as surrealism, Renaissance composition, nonsense poetry, Victorian illustration, and most significantly, the work of Lewis Carroll. The book is such a remarkable collection of passions that, despite its status as an adaptation, it is a product of a single man's obsessions and compulsions, a book that Singh himself was uniquely qualified to create.

Mahendra Singh was born in Libya ("against his better judgment," reads one of his official bios) to German and Indian parents. Although he lived in Washington, DC for many years, he is now a resident of Montreal, where he works as an illustrator. His full-length comic debut was the (very) short-lived Adventures of Mr. Pyridine, published by Fantagraphics in 1989. Pyridine is a collection of surreal vignettes heavily influenced by the collages of Singh's long-time love, Max Ernst, whose collage novel Hundred Headless Woman is touched on briefly below. Compared to the virtuoso performance of Snark, Pyridine is visually crude, but the comparison is illuminating—Singh has spent the intervening decades outside of of the comics field, working as an art director and illustrator, refining his visual craft and personal obsessions in two parallel tracks which in Snark have finally conjoined.

I spoke to Singh for several hours in late March, in a wide-ranging conversation that ran the gamut from art history to Heavy Metal to flogging the proletariat. Singh is quick, funny, and eloquent, and has the ability and inclination to hold forth on a variety of subjects. This sometimes led us to some unexpected detours which I hope you'll indulge.

I spoke to Singh for several hours in late March, in a wide-ranging conversation that ran the gamut from art history to Heavy Metal to flogging the proletariat. Singh is quick, funny, and eloquent, and has the ability and inclination to hold forth on a variety of subjects. This sometimes led us to some unexpected detours which I hope you'll indulge.

ROBINSON: To start practically, how has the book been doing for you guys?

SINGH: I have no idea. I haven’t really talked to Melville House about it yet. I’m assuming it’s not a catastrophe [laughs] because they are talking to me about other projects, vaguely, tentatively, hesitantly. I first did this as a proposal for another major New York publisher my agent got me an in with. I gave them a bunch of ideas, and this was one of them, and they rejected it out of hand. I don’t blame them, because it is a little odd. So I just went ahead and did it on my own over the years. It took me about three years. And I think I sent to almost … probably thirty to fifty people. I mean, I sent it all over the world—I sent it Gary Groth, I know that. And he was very nice about it, actually.

ROBINSON: What’d he say?

SINGH: He just said it wasn’t "for us." [laughs] I could see his point. The problem with The Snark is it's really not a contemporary comic book. So many new, neat things are going on in the world of comics in North America. Some of it is crap, of course. But some of it is pretty cool. And this book is very old fashioned, I think. First of all, the page structure is straight from the 1930s. The pace is a bit slow, the text is slightly difficult. It has a very old fashioned air to it—the visual style. I can’t remember the last … well I guess the only other guy doing this is Crumb, really. I mean, doing this much cross-hatching.

That’s why, when Melville House came a-calling, I was first of all stunned and I realized that this would require a leap of faith and I was all for it. There've been plenty of other comic book versions of Lewis Carroll done, though The Snark has never been done before. I don’t do a lot of comic books, though I love them more than anything else I do. When I do a comic, I really try to give a lot of value for money. I have nothing against minimalism, and I think it’s the only appropriate choice in certain situations, but I like a comic book where it takes you a month to get through it. Because I figure, if you’re going to be paying any where from ten to twenty bucks for a book, you should get some value. This is something I learned in magazines and newspapers: never underestimate the idea of "value added." You give people something for their money. And there’s a lot of very successful comic book artists who are doing their pages extremely fast, and there’s not that much in them, visually. And that’s okay for them, but it’s not for me. I want people, especially young people, to get an object in their hands which first of all has a great text — it's a very cool poem — and then when they realize there’s a ton of crap in there, they're not going to finish it in one sitting. They’ll skim through it in one sitting, and then maybe take another two or three sittings to get the poem and then they can slowly, at their leisure, realize that panel after panel is full of goodies. It’s like a Sudoku, really.

ROBINSON: What do you think about Carroll’s place in popular culture?

SINGH: Pretty grim. [laughter] Yeah, it’s pretty grim. I have to tell you that 99.99% of what you read on the internet or in most publications is complete rubbish. It’s just not true. First of all, Lewis Carroll was not a crackhead. I saw that in some review today, in fact. He wasn’t smoking cocaine. He was not into drugs. He was not an epileptic. He was not a pedophile. I mean, I could go on and on. [Robinson laughs]

ROBINSON: Sorry, you have to clear this up for me. Was he Jack the Ripper?

SINGH: No, he was not Jack the Ripper [laughter]. He was … I’m trying to think of some other criminal. We’ll make him into that. I don’t know. He was Sweeney Todd, that’s for sure [laughter]. He was a college professor. If you’ve bumped into those, and I’m sure you have, most of them are not the most exciting people. He was a college professor who had a very unusual mind and the only way he found for his flights of fancy to really work was to couch them in the form of these very odd stories. And since he had a very mathematical and precise mind that was also given to daydreaming, the results are very unusual. For instance, the Tim Burton movie, Jesus Christ [laughter]. Did you see it?

ROBINSON: I kind of saw it, if you count grimacing, covering my head with shame, and not being able to focus my eyes because of the damn 3D glasses on my face … then yes, I saw it.

SINGH: I know some of the people involved in the movie and, in their particular fields, they did a sterling job. I thought technically the movie was extremely well made. But, as I hope you realize, it had almost nothing to do with Lewis Carroll’s book Alice in Wonderland. And that again shows you the power of Lewis Carroll, because basically they took something, they just slapped his name on it and a few elements from the stories, and they made like a billion dollars or something. The girl was pretty good, though.

ROBINSON: Yeah, she was outstanding. And, you know, like most Hollywood movies – there was some actual skill involved in many aspects of it. But I wonder about people … you know, for an entire generation of children, that’s Alice in Wonderland.

SINGH: Yeah, I know. That’s a pretty spooky thought because it was basically aimed at the goth niche. And what Lewis Carroll would say about the goth niche... I suspect he would have grabbed a riding crop and delivered some hearty blows to the heads of the lower classes. And huzzah for all that [Robinson laughs]. There are times, let me be blunt, and I want this in The Comics Journal: There are times when the lower classes need to be put in their damn places. And that was one of them [laughter]. We can’t have pond scum or bottom of the pond scum crawling to the top and making cultural choices. If we continue – if we visual and verbal people continue to whore ourselves out so shamelessly, we’re going to get what we deserve, which is nothing.

I understand the difficulty of making a mortgage payment and putting food on the table, believe me. And you do have to make compromises at times. But at times, the compromises are so vast that they are no longer compromises [laughter] … when you have sold your soul to the forces of hell... actually worse, because I think Satan has better taste than many of these people in popular media. I mean, you know Satan is going to have the most perfectly furnished place possible [Robinson laughs]. He’s down there, having drinks with Michelangelo and Christopher Marlowe and Shakespeare and Milton, I would hope. That would be funny [Robinson laughs]. Milton is surprised, of course, but he was always surprised—besides, he was blind, he wouldn’t know. But the point is, if we keep cheapening our visuals—let’s just focus on visual culture, otherwise, I’ll go nuts—we’re going to wind up with stick figures pretty soon. There are popular comics that you and I both know that are composed of stick figures.

ROBINSON: I was about to break the news to you [laughter].

SINGH: I do get out of the house occasionally, on the Internet, and I looked at that one. And, again, I’m not going to throw stones at the guy – the guys, plural – whoever is doing that, because there are niches and they need to be filled. It’s not my niche, and I don’t think it’s a very productive niche in the long term, because what we’re really doing is that we’re telling our kids that crap is cool. And in North America, particularly, you get a kind of mantra or response to that where a guy will watch a really shitty movie and his wife will complain, or vice versa, and he’ll say, "You know, it was a really hard day at the office and I just wanted to relax and this was on." And it’s always on. And there’s no alternative. There is an alternative, but this guy is not going to turn it on. What he's really saying is the exact opposite: there is something better on, but I’m not going to watch that because I am tired. And the reason he is tired is because there probably wasn’t much in his brain to begin with. Which is because he has reached a pay scale way above his mental capacity, which gets back to flogging the lower classes. But anyway [laughter] the point of it is [laughter] … that’s why I’m in Canada.

ROBINSON: I’m sorry, are you promoting your book? Or …

SINGH: Yeah, damn right. [Robinson laughs] I know what Gary Groth likes in The Comics Journal, I’m going to supply him with a bit of it. Why not? You want me to mention Harlan Ellison? [laughter]?

ROBINSON: No, I think you probably better not.

SINGH: I used to work at a paper, and one day a guy who knew he was about to get fired went berserk. And he inserted in almost every single article, running almost every article that day was ‘steely determination’. [Laughter] The weather that day … the rain fell with steely determination. The Blue Jays won the football game with steely determination and the corn crop was coming up with steely determination. And from that day forward, the owner of the newspaper, if you put the phrase steely determination in an article [laughter] you were out of there so fast. So I think Harlan Ellison for Gary Groth, probably on the advice of his lawyers, probably qualifies.

You know, that’s always what I liked about The Comics Journal. I think Gary Groth also feels that the lower classes at times do need a good flogging. [laughter] Especially when they’re making drawings—bad drawings. And I wanted so much with my Snark to show people what’s possible in a conservative way. It’s time. I got interested in comic books in the ‘70s, when I was teenage. My mother’s second husband was an art director and he was wasting his life in a horrible studio job, and one day he came home and before tossing off his bourbon and water he handed me this book and he said, "Hey, all the other guys at the office are looking at this thing." And the guys at the office were a pretty wild bunch, let me tell you. They had a good time at the office. And it was, I think, the first issue of Heavy Metal. And at that time I was very interested in the old-fashioned line art like Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein, Lucas van Leyden, Gustave Doré. And I was a verysedate young man, but very interested in classical ink pen techniques. I opened that thing and was like, "Holy shit, what is this?" There was Moebius in that issue and Bilal and Nicole Claveloux. Those three alone... if you’re a pen and inker Moebius is pretty high on the list of guys you want to rip off as much as possible [laughter].

From that moment I knew I had to make comic books -- it made me realize there could be a lot more to comic books than the North American model. Because I never cared for comic books as a kid -- the North American ones. I thought they were pretty crappy, most of them. I don’t understand what’s up with Jack Kirby. He was a very competent guy and I bet he busted his butt doing all that work, and more power to him. But his stuff is just so boring to look at. Jesus. And the vehicles he got attached to. How can you look at those plots with a straight face? I couldn’t. When I was a kid, the only comics I ever looked at was the funny animal stuff, I liked that. Carl Barks. And Heckle and Jeckle. I liked that because they rhymed, too [laughter]. For me as an artist I jumped straight from 16th-century German line art to 1970s French alternative comics and shortly after -- I think that was around the time my aunt gave me Max Ernst, but to me, it was all just one kaboom in my brain. It was like a supernova, man. Blowing up my brain [Robinson laughs]. But no, it worries me because I see the same tendencies still in North American comics. It’s like Hans Rickheit, I’m sure you know about him. This is a guy we should be keeping our eyes on because he’s doing something different. It’s really, really different. He’s moving forward. I correspond with Hans -- he’s broken the cycle of American comics where you sacrifice the art for the story and the story isn’t that good to begin with [laughter]. That’s your pull quote right there. [laughter] Yeah.

ROBINSON: You keep on bringing the interview out into the meta interview in the same way that your Snark pulls back.

SINGH: Oh yeah, absolutely. We’re pulling back frames now. What we’re really talking about is the decline or fall of human civilization here, man. It’s a big project and we’re sworn to fight it. But American comics… it’s like some kind of zombie movie or something. It keeps resurrecting itself and then it gets another shot in the heart and collapses. It’s resurrected itself now, and it’s doing well financially, which is a good thing. But what really puzzles me about a lot of comic books, especially in the United States, is we’re not making money at this. Very few of us are making any money at all. I doubt if you are, and I know I’m not. [Robinson laughs] If we’re going to do something and we love it so much, let’s do the best we can. I mean let’s really make this stuff look good. What the hell man? You know, life is short. Tomorrow you could be run over by a beer truck or whatever [laughter]. You might as well do something that your kids can be proud of. And why peddle crap to kids.

ROBINSON: [laughs] That’s a great point.

SINGH: Another pull quote.

(continued)