ROBINSON: I had had almost no exposure to the Max Ernst collages before …

SINGH: Aren’t they cool?

ROBINSON: I read Hundred Headless Woman this week and it was just incredible.

SINGH: Yeah, and it just blows your mind. I grew up mostly on a farm in Virginia along with my brother and foster brother and so forth. My father was a college professor, my mom was a farmer. And then they divorced. As I mentioned before, my mom remarried a guy who was an art director and illustrator … which kind of got me into the business. She’s German, and she had this really cool hippie sister in Berlin, my aunt. Who chained smoked and drank a bottle of white wine every day of her life [laughter]. And partook of various illegal substances with absolute gusto.

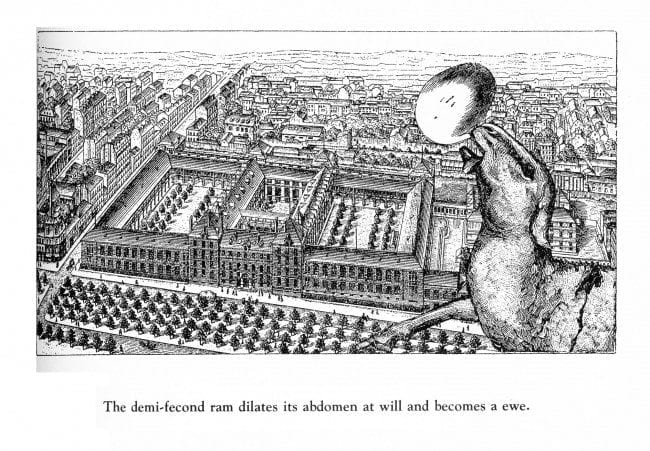

I was fifteen or sixteen and [my aunt] gave me that Dover edition of The Week of Kindness by Max Ernst. She said, "I think you’ll enjoy this." It totally changed a lot of directions for me. It’s stuck in my head since then. And amongst other things, it's because he looked so authoritative when he uses those collages, it gives you the feel of that classic 19th century – late 19th century – storybook illustration. Like Gustave Doré and those guys whom I adored as a kid anyway. I kind of came at it at the angle of a 19th century kid, really. He really played a nice game with that technique.

ROBINSON: How much drawing back into the collage did he do?

SINGH: He may have inked up a little bit here and there, but I don’t think he went very much into it. He made quite a large amount of them. He was taking old periodicals and stuff and just gluing them with glue and pasting them up. He had such a wealth of stuff to work with because that stuff used to be very common. In fact, I’ve done some Ernst collages like that. One of the continuations of Mr. Pyridine was done in that technique.

Unfortunately somebody ripped off my whole stash … I had a huge stash of Victorian engravings at one point. Nice stuff. They all vanished somewhere. But it’s not that hard when you have enough on hand. You can always find a shape that suits what you need to do and you just need a very sharp razor blade and glue. Just very careful … very slow and careful.

ROBINSON: He didn’t shoot a stat of a larger size or anything like that?

SINGH: I don’t think so. I’ve seen, once or twice, a few of his things photographed of the originals and as far as I remember he pretty much did everything as is, torn from the periodical or book he was using. He glued it up on some kind of board and that was it. He did a lot of it, you know?

ROBINSON: Really incredible, and I saw the connection to your work pretty strongly. Not to get too far afield, but it’s amazing to me that there’s this whole history of illustration that is so poorly preserved. I mean the big guys, like Doré, we have stuff of his that’s still around and you can find in pretty good shape. But even Phiz – the Dickens illustrator – you can find reproductions of his stuff, but it almost uniformly looks terrible.

SINGH: Yeah, I know what you’re saying. There’s a huge chunk of Western illustration techniques and styles that is vanishing into an abyss – a black whole – simply because it’s not being reproduced properly, for one thing, and not being disseminated. The reproduction is a bit of a problem because, unless the original wood block exists somewhere, you’re not going to get very nice, crisp first generation print. Although, occasionally, that does happen. Like, for instance, some of the Tenniel stuff [John Tenniel, original illustrator of Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass]. Some of the blocks still exist, and they’ve been pulled again. They look incredible. But unless you have a very careful cameraman working, and you know, very careful production department working on it. Even using the second generation printed piece—it’s hard to pull off. Especially with that tight line art. That’s why Dover is so important because most of their books are pretty damn good.

ROBINSON: I got an opportunity to see an 1870 edition Dickens book that had some tipped in illustrations.

SINGH: Right, the wood engraving, where they tipped it in afterwards. [actually copperplate etching in this case]

ROBINSON: It’s just phenomenal, and it’s still in great condition, it’s just sitting here in this university library. And there’s probably hundreds of thousands of copies of this illustration out in the world in a bastardized form. And here’s this beautiful version of it that was printed in 1870 or whatever.

SINGH: Well, what is making your eye jump up and say, “Jesus, that’s great,” is the beauty of letterpress printing. Now, of course, the illustrations in those days were being printed separately from the type. But if you look carefully at the type it looks unusually crisp and nice. That’s because the ink is sitting on top of the page and it comes off a metal form and it’s going to be crisp if the printer knows what he’s doing. And then again, because you’re looking at a wood engraving, you’re looking basically at a very detailed wood cut. And again, the ink is sitting on top of the page, because you've become used to looking at offset, which is lithography printing since the ’50s or whatever. And in that case, the ink is almost a film on the page. And it never gets that optical snap. So letterpress always rules the day. It looks so darn good. Also, some of those old books, they’ll sometimes have etching or steel engraving illustrations tipped in. And again with an etching or an engraving, the ink is sitting on top of the page – even higher in fact – and the look to your eye is just dazzling. So we’ve moved backwards. Offset just doesn’t look that good. It never has. And it was never meant to. It’s just cheaper to do. And also, because when you look at these modern [reproductions], you’re looking at third or fourth generation [copies]. Even with the best of intentions, it’s going to look like crap.

ROBINSON: And if somebody’s just not willing to go back to that source …

SINGH: Yeah, you’ve got to back to either the best possible copy—printed copy if you can’t find the original blocks, which is kind of difficult—and set up a really good production, and really work like hell. But you’ll never beat letterpress, ever. These technical guys can jump up and down all they want, but the older guys know that letterpress rules. It just looks … even the type looks so good. God, it just sits on that page, very crisp. Very muscular. Ah, good stuff. [Robinson laughs] You’re getting me all worked up because I spent many many years doing newspaper and magazine work, not just illustration, but design, art direction, pre-press, color correction, typesetting, you name it. I set a lot of type, actually. I’ve set a hell of a lot of type in my life. I started setting type in the phototype days, which itself is, well, pretty weird when you think about it, [laughter] and when the computers came in, we were just shocked, to tell you the truth. It was just such rubbish. Because at first, you would take the Mac output and slap it and paste it up directly on a flat, which is the dumbest thing. It was really stupid. Anyway …

ROBINSON: Well, yeah. And you compound that with the fact it doesn’t appear that very many people know what they’re doing anymore. Last month Harper's printed a review of a woodcut novel. Well, every single woodcut they used to illustrate the review was printed CMYK. [full color process, rather than black and white, causing a "soft" broken up and colored edge instead of crisp black line]

SINGH: Yes. Life goes on, doesn’t it? You know, you’ve given me another soapbox to stand on and I’m wondering whether I should just stand on it and rant away.

ROBINSON: Please.

SINGH: Okay, let’s get on the soapbox. Speaking as a print professional working since the ’80s: Since the introduction of the personal computer, it has become so cheap to put out publications that there is no need any longer to have a large staff. It used to be that a magazine like Harper’s had thirty guys on staff. I doubt if they have a production shop of two or three people now, if that. Usually what you do in a magazine is that you’ve got one older guy who’ll be in his forties — and that’s ancient — and then you have a bunch of guys in their twenties. And they mean well and they’re wonderful young people but they’re being sold short. Because they work so hard and the older guy is so exhausted he doesn’t have time to really show them too much. Because it used to be in a shop a guy would show you stuff. And he’d, you know, drink beer doing paste-ups, and do other things during paste-up. [laughter] And that was good. But these guys, they were too expensive so they were gotten rid of. So you keep one guy as the nucleus and the rest of the shop was young guys, and you let them burn out pretty quick. Because, over time, it’s free. Right?

ROBINSON: Right.

SINGH: And that's another soapbox to stand on. Because, in the old days, they paid for over time.

ROBINSON: Right.

SINGH: And so, if an editor decided to make 20,000 changes, one after the other, each change required a new set of type, sent out from a type house that was usually off site. Which meant delivery costs, too. So now days you’ve got an editor who’s standing over some poor kid who’s banging away at type on a Mac and you know how that goes. He keeps changing and changing and changing. Because there is no financial incentive for him to say stop. So you’ve got a total burnout situation going on. You’ve got a kid who is flipped out, exhausted, he’s going to quit. So there’s no way for the older guy, even if he wants to, to sort of start passing on technical tips and stuff to the younger guy. So that sort of tradition is dying out. I don’t think the schools are doing too much about it, not that they ever did to begin with. They seem more interested in minting diplomas and sending people out to make even less money.

ROBINSON: There’s the question about whether anybody, besides you or I, or enthusiasts in the area, gives a shit, you know? They look at it and…

SINGH: Yeah, that’s an extremely good point. And you’re actually really starting to get into the heart of the problem. The thing of it is, first of all, that a lot of the things we do on the printed page are not as important as we think. A nicely designed page is a wonderful thing, and it might get you a job and a portfolio. But as long as the reader can easily navigate the page, easily get in the information you’ve presented, possibly come away with an emotional glow, you’ve done you’re job. Navigation and simplicity of use are the name of the game in good design. It’s not about making a fancy layout. But there’s a flip side to that because the chain has been broken, the chain of tradition. More and more you have art directors and publishers and editors in the field, in all periodical fields and even books, who no longer really have been exposed to good-looking work. There’s many art directors now who genuinely think that clip art looks great [laughter]. Because they’ve never seen anything else. I mean they really haven’t. I like to think of it as, if you look at rubbish, you will make rubbish. And if you train a generation to look at rubbish, they are going to repeat the rubbish that they think. To them, it’s a standard – it’s a classic. You know, thirty years from now, those clip books are probably going to be classics [laughter]. I’d say it’s hilarious.

ROBINSON: And that’s a terrifying thought.

SINGH: There’s going to be guys trading clip books and there’s going to be blogs about famous clip artists, and you know … jeez. [laughter]. One of the reasons I set The Snark up the way that I did, is because I’m really pissed off about what’s going on. And I know part of it is just human nature. But I do deeply worry about younger artists and illustrators, comic-book guys and everyone in the visual arts. They’re losing touch with the past. And sometimes that’s a good thing, because some of the past is crap. You know, Victorian typography is crap, and don’t let anyone tell you different. It’s rubbish: great technology, terrible layout, terrible fonts. But in my book I tried really hard, if you look carefully at every panel, to give basically a history of Western art and culture and literature and philosophy and architecture and music. And not just the snobbish stuff either. I tried to go all the way from Plato all the way up to The Beatles, basically. There’s some George Herriman in there … just a little bit of everything.

I wanted to make it into a surrealist Where’s Waldo. Not just surrealism, but art in general. I’m hoping that some kid will look at my Snark and say, "Wow, that’s a cool poem," read the poem, and say, "Man, those are weird drawings." And he’ll maybe start to think about it, and maybe he’ll accidentally bump into a drawing or painting on the Internet and he says “holy shit, that’s from The Snark," but it’s not from The Snark, it’s from Rafael. And it’s all about Plato and Aristotle standing on a street corner. One’s pointing at the earth, the other’s pointing at the sky. And there at their feet is another guy, and this is the history of Western philosophy and this is also Rafael.