It would be reasonable to assume that you, a reader finding yourself on the website of a magazine titled The Comics Journal, are able to read comics. I don’t mean that you are ‘literate’ in the regular meaning of the word, that you know your ABCs, but that you think of yourself as a person able to parse the various components of a comics page into narrative information. You may even be surprised, since you were probably able to do this from around the age of five or less, that there are citizens who have problems in this department. On the other hand, you may have once or twice given a comic to a regular citizen to read and found them baffled by it. This problem was addressed by Rod McKie in the comments to my last outing here:

I think what we tend to overlook, perhaps because of our over-familiarity with the subject matter, is that not everyone can read comics… In an article for the Independent, Thomas Sutcliffe mentioned the ‘defiant pride’ some reviewers had exhibited when it came to discussing anything as lowly as a ‘graphic novel’ when he was chairing the BBC Radio 4 program, Saturday Review. On one show, two guests admitted to having real problems understanding comics, or graphic novels

…Of course it could be that they feel the need to decry anything that smacks of the vulgarity of pop culture, but it could just be that we need to do a better job of explaining to the uninitiated, how the various elements of comic books, the text, the typography, the colours, the drawings, all work together to tell a story.

I once found myself onstage for a TV book show and challenged to address the same question, as to why some people just can’t read comics. I can’t remember what I said as it was later edited out, but I think I observed that the same people have no difficulty navigating through the complicated mix of text and image in an average women’s magazine. My blather would have been mercifully cut because I launched into an insane mimicry of a theoretical middle-aged woman in tears from not being able to interpret the TV guide. If, in the aforegoing, you find me focusing somewhat upon women, as has just been pointed out by my proof-reader, this is because the people who have said to me that they cannot read comics have all been women. Before jumping on it, ask whether the statement, ‘the readership of comics in the last forty years has been predominantly male,’ is true or false.

I have in my l life met one or two people who were so well brought up that they had never read a comic. They tended to have an underdeveloped sense of humour. Whether there is a correlation between naughtily spending your lunch money on a Betty and Veronica Digest and having a well-honed grasp of the funny, I will leave to another time. But I have also met people, pictorially literate and unfazed by contact with the vulgar, who do not know what to make of a modern day comic book. I sympathise. The fact of the matter, make no mistake, is that I am on the side of the perplexed and mystified. Most comics today are visually unintelligible except to a few.

It could well be that you are one of the few, that you feel that comics publishers should not be pandering to the general public and that comic books are just how you like them, with their forty plus years of stylistic inbreeding and complicated continuity. Perhaps you are a kid and, like me, you think kids owe it to themselves to keep loads of stuff secret from their parents, and the secret language of comics is a part of that. Great. Comic book publishers love you. However, with the shrinkage of the market for comics, these same publishers are trying hard to get back that general readership they lost a long time ago.

Occasionally I see a well-regarded comic wander across the view of a regular person. It happened on my travels recently when I was a houseguest of a friend, a 70-year-old lady who makes her living as an artist. While I was there she was working on some etchings to go into a limited edition anthology of poetry on the subject of war. I mention this simply to show that this person understands pictures. The mail arrived and among it there was a volume of Bryan Talbot’s Grandville, which her husband had bought. She opened it and checked it, in order to let him know by phone that it had arrived. While idly looking at the pages she confessed to me, after putting down the phone, that she didn’t know how to read these graphic novel things. I took a quick look and said, “My first thought is that I can completely understand what you’re saying, because I can see that the author in this case has broken at least three of the basic rules of comprehension.”

Rather than ‘the’ rules, I should say rather that they are ‘my’ rules. These are a bunch of principles I quickly worked out once when I needed to give a college lecture about making comics, and had been encouraged to get a little bit technical if I so desired. So they are rules, toward a rhetoric of the art of comics, for the purpose of commanding the means of expressing oneself in the most effective way. If you don’t care for a curmudgeon like me making the rules, hey, it’s my gift to you. If you have no use for it, put it in the back of the cupboard. Just remember to serve the drinks out of it when I'm visiting.

So let me use Grandville as an example, and this is not to be construed as a review or an opinion of the book. It is published in the USA by specialist publisher of comic books, Dark Horse, and in the UK by mainstream publisher of books, Jonathan Cape. The book is thus useful because it straddles the comics store/bookstore divide. Furthermore, I’m using Bryan Talbot here, not because he would be my first choice to illustrate the points I want to make, but because he just happened to be the one on the table when the discussion came up. He’s an award–winning artist, with justification, and my purpose is to show that even the best of us are less than accommodating to those who are unfamiliar with conventional comic-book syntax. I don’t want to ambush him unfairly, being a brother of the brush, so it’s a page I know he’s pleased with as it was used in the promotion of the book. It is a decently vivid and strong comic book page, and you should be surprised that anybody could be unsure of it. If you show it to your granny and she has no trouble with it, that’s nice; give her my regards and light her pipe for me. It’s from the French edition, which doesn’t matter for my purposes.

There are some great and arresting images in Grandville, like the one above. The story is a complex piece of speculative fiction that was nominated for a Hugo award. Science fiction people love it.

Our page above is very much in the comic book idiom. By that I mean that it’s in the American style. They don’t traditionally call them ‘comic books’ elsewhere, except insofar as the American tradition has spread far and wide. Artists and writers who work in this idiom do not tend to be self-aware. To tell them this is just one idiom out of many would be like telling them they speak with an accent. As we know, it’s other people who speak with accents. All kinds of things go to make up this idiom, from the way the art bleeds to the edge of the page, and the way the figures stand in relation to their word balloons and the panel borders, all the way down to the brushed technique of the ink-lines. That the pictures are crowding in upon each other alarmingly is also idiomatic, and it takes a moment to figure out that the middle row of panels is not so much inset into the large upper panel as that all of them are set against a black ground, with slight overlaps.

Our page above is very much in the comic book idiom. By that I mean that it’s in the American style. They don’t traditionally call them ‘comic books’ elsewhere, except insofar as the American tradition has spread far and wide. Artists and writers who work in this idiom do not tend to be self-aware. To tell them this is just one idiom out of many would be like telling them they speak with an accent. As we know, it’s other people who speak with accents. All kinds of things go to make up this idiom, from the way the art bleeds to the edge of the page, and the way the figures stand in relation to their word balloons and the panel borders, all the way down to the brushed technique of the ink-lines. That the pictures are crowding in upon each other alarmingly is also idiomatic, and it takes a moment to figure out that the middle row of panels is not so much inset into the large upper panel as that all of them are set against a black ground, with slight overlaps.

The first of my rules that are in danger of being ruptured is

Rule #1: All the information necessary to understand the drama of a sequence must be contained in every panel of the sequence.

I extrapolated this idea from a 1960s interview with Bernard Krigstein where he complained that the fragmentation you get in many comic books works against pictorial logic and undermines the drama that the artist is supposed to be expressing. Thus, if you take Krigstein’s masterpiece, the short story Master Race, and look at the second last page (below), you will observe that in eleven panels, ten of them show both the man chasing as well as the man being chased. Add five at the foot of the previous page, and one at the top of the next one, and you get a run of seventeen panels all showing both characters (with only one break to insert a poster-like reminder of the camp commander in the time of his crimes). The subject of the drama is the relationship between them, and there isn’t a single panel, such as one cutting to a close-up or some other detail, where you could isolate it and say that we temporarily lose sight of this.

Looking at the Grandville page. It’s clear enough that the scene is an interrogation taking place in a small smoke-filled room, if we allow the ceiling lamp that we can see to stand in for the rest of the room that we can’t see. We are to presume that the badger is tied to a chair. There is no chair to be seen, or bound hands (having often read comics to little children, I would be anticipating the question “Why does the badger have no arms?” See elsewhere, my Rule #5: In a visual medium, a thing does not exist unless it is seen to exist). The chair may be on an earlier page, but that is part of the problem. Can we assume that the virgin reader knows they are supposed to look back there for the missing parts of the image? If you were to isolate the centre panel (below), is there enough information in it as a picture to make sense of what is happening without referring to all the other pictures? Do we still know it’s a smoke-filled room and that a character is tied to a chair? What is keeping that pistol grip suspended in the air? And to whom is that balloon tail pointing? Can we be sure the reader knows about the convention of characters speaking from off-panel, rather than the just-as-likely possibility that the balloon is coming from somebody over in the succeeding panel? (In this case, as it happens, the speaker is in a dominant position in the next panel, and the bridging balloon tail does arrive at the lettering spelling his name. A decent cartoonist will connect things together like this as he goes along.)

Looking at the Grandville page. It’s clear enough that the scene is an interrogation taking place in a small smoke-filled room, if we allow the ceiling lamp that we can see to stand in for the rest of the room that we can’t see. We are to presume that the badger is tied to a chair. There is no chair to be seen, or bound hands (having often read comics to little children, I would be anticipating the question “Why does the badger have no arms?” See elsewhere, my Rule #5: In a visual medium, a thing does not exist unless it is seen to exist). The chair may be on an earlier page, but that is part of the problem. Can we assume that the virgin reader knows they are supposed to look back there for the missing parts of the image? If you were to isolate the centre panel (below), is there enough information in it as a picture to make sense of what is happening without referring to all the other pictures? Do we still know it’s a smoke-filled room and that a character is tied to a chair? What is keeping that pistol grip suspended in the air? And to whom is that balloon tail pointing? Can we be sure the reader knows about the convention of characters speaking from off-panel, rather than the just-as-likely possibility that the balloon is coming from somebody over in the succeeding panel? (In this case, as it happens, the speaker is in a dominant position in the next panel, and the bridging balloon tail does arrive at the lettering spelling his name. A decent cartoonist will connect things together like this as he goes along.)

In panel #4 the dog and rhino seem to have moved in relation to the tied–up badger, but they’re back to their positions in the last panel, unless there is another dog in the room that I don’t know about. This creates a feeling of manic action, of a great deal happening that may not be happening. And finally, in the last panel on the page, where is that other character, the French Inspector Rocher, coming from? Was he in the corner of the room all along, or has he come through a door that is nowhere visible? Sure, every room has a door, but how much can we take as given? If the whole page were isolated from the book we might not even be sure it’s a room in a building. Without the indication of walls, we might think we’re in a hole in the earth. Naturally, reading the book from the beginning might alleviate such difficulties, but our virgin reader, having flipped through it, looking for a way in, an indication of potential enjoyment, an enticing excerpt, may not make that conclusion.

In panel #4 the dog and rhino seem to have moved in relation to the tied–up badger, but they’re back to their positions in the last panel, unless there is another dog in the room that I don’t know about. This creates a feeling of manic action, of a great deal happening that may not be happening. And finally, in the last panel on the page, where is that other character, the French Inspector Rocher, coming from? Was he in the corner of the room all along, or has he come through a door that is nowhere visible? Sure, every room has a door, but how much can we take as given? If the whole page were isolated from the book we might not even be sure it’s a room in a building. Without the indication of walls, we might think we’re in a hole in the earth. Naturally, reading the book from the beginning might alleviate such difficulties, but our virgin reader, having flipped through it, looking for a way in, an indication of potential enjoyment, an enticing excerpt, may not make that conclusion.

The second of my rules that are under threat here concerns the reading order of the speech balloons. There are worthwhile books, on the subject of making comics, which will tell you that the medium uses a ‘nested system,’ and that the reader is to absorb all the information in a panel before moving on to the next panel. In fact, this is not how things really work. The reader’s eye, even the eye of an experienced reader, will go where all the indicators tell it to go. After reading the contents of one balloon, the eye is likely to go to the next nearest balloon, even if that balloon is in another panel and the eye has not yet taken in all the balloons in the current panel. If the next nearest balloon is not intended to be the next one in the sequence, then the cartoonist risks losing control of their narration. Grandville has many pages like the above where all the balloons look, certainly to the lady that I was visiting, as though they are barrage balloons over a city, not interacting with the life and noise below, hanging there to keep invaders out, rather than invite readers in. One of the criticisms heard from those folk who don’t know how to read a comic, is that they don’t know which they’re supposed to do first, read the words or look at the pictures. Often the two appear to belong to separate systems, not completely integrated, and there are no cues on a page like this to make it clear what the reader should do.

Rule #3: Speech balloons should follow a system that can be intuited and doesn’t need to be explained.

On the Grandville page, the sequential problem occurs more than once due to the habit of placing balloons at the foot of a panel. In the top panel, with plenty of time to compose this page, the artist could have avoided putting that balloon in the same pictorial space as the dog, bisecting its arms. Is it possible that our virgin reader might find this kind of placement confusing? On another page there is a panel showing a character eating dinner. The panel contains just the character and his dinner, except that a speech balloon is covering his plate. This tendency is an indigestible aspect of comics’ technique that came with the ‘Marvel method,’ where the balloons were not composed at the drawing stage, but written and added in afterwards. With inadequate space anticipated for them in the plan, balloons are often placed on top of figures or other art details. Long-time comics readers are accustomed to this by now, but what is the unaccustomed reader to make of it?

After panel #2, at the left side of the middle tier, I’m reading the balloon at the foot of the panel. There is no way that I, even as an experienced reader of comics, am going to keep my eye from accidentally reading the balloon belonging to Rocher, in the coat and scarf, in the final panel, well ahead of his intended surprise entry two panels before this. You, likewise a practiced comic book reader, might just be able to avoid it, but I bet you don’t.

This touches on another Campbellian rule:

Rule #4: Timing only exists in comics if the reader agrees to play the game.

We talk about timing in comics, but really there is no time except in a periodical sense. i.e. 'next issue'. All the pages of a comic book arrive simultaneously. If it happens that Magneto shows up surprisingly on the last page, I've never met a kid who didn't already know this before he got the book out of the store (before you put your hand up, I’ve never met you). Unlike the movies, where good or bad timing is a measurable fact, in comics everything else on this subject is fiction. And like all good fiction, it requires a suspension of disbelief on the part of the reader. In fact it requires a little more than that. It requires complicity between the artist and his audience. This thing that we do, we are going to pretend that it is analogous to time. That is the unspoken agreement at the outset. And because it is unspoken, we cannot complain that a reader didn't know about it, especially in these days when we expend so much effort in attracting new readers. We need to offer them a contract with no hidden clauses. And beyond that, we have no control. In prose novels it takes an act of choice to read the ending ahead of getting there, but in comics it can happen so easily by accident. Part of the humour, or drama, of comics should involve an allowance for that. As artists and writers we cannot prevent the reader's seeing ahead accidentally any more than we can stop some lug from giving away the score of the match whose TV replay we are going to watch fresh later tonight.

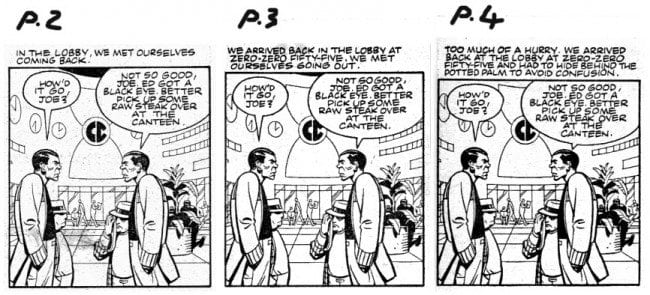

I find myself recalling a very clever piece of work that Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons made in 1983 titled Chronocops, where the whole short story was playing mischievously with the concept of time. The authors quite cleverly laid all the information before us in panel after panel but we didn't see it because we were looking for something else. At one point the cops arrive back at HQ in an earlier time slot and have to avoid themselves in the lobby.

When we flip back the pages to the first appearance of this scene, we see what we didn't see before because we weren't looking for it, the two characters half-hiding behind the potted plant.

For me the conventional three-panel gag can never work again because I know there's supposed to be a punch-line in the third one, and If I haven't guessed it then I've glimpsed it. The third panel is not distant enough in space and time for me to avoid reading it simultaneously with the first. To summarize, if your piece of work involves some intricate business about the order of reading, a 'spoiler warning' ain't going to cut it. You cannot depend upon conventions of the form. You need to work it into the fiction in some way.

On the one or two occasions when I bring out my rules for a lecture or something, I like to finish with one that was meant as a laugh, to deflate the serious complicatedness of the others:

Rule #10: Remember to put at least one pair of feet on every page.

It is also known as “the feet rule.” Sometimes it’s not needed, as for instance in the Grandville page it might create space that would diminish the claustrophobic feeling. On the other hand, sometimes just asking the question can help the artist see solutions to the problems that are being experienced by that hypothetical virgin reader. For instance, If we could see the badger’s shoes just once we’d probably also see the legs of the chair, and if Rocher were full figure, the door would probably suggest itself into the composition.

“But who cares?” says the lover of comic books, and I agree wholeheartedly.

For the curious enquirer after the rest of my rules not mentioned above, some are not as interesting and one was so stupid that, like the 18th amendment, it had to be repealed.