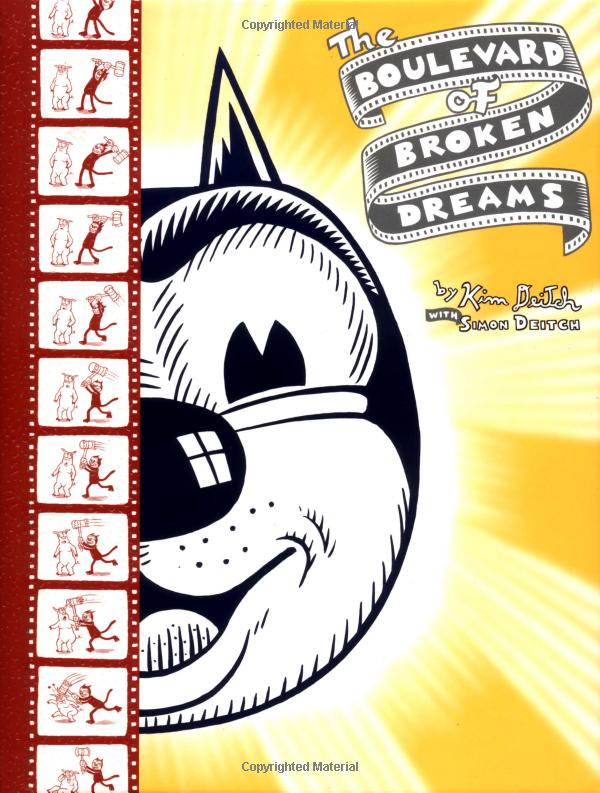

Kim Deitch’s Reincarnation Stories is one of the most significant graphic novels published in North America this year. Few artists working in the comics form today can claim the deep experience and personal history Deitch brings to his work. And even fewer have worked so consistently and doggedly from the underground days of the East Village Other up to the present moment. More importantly, Deitch has produced a significant body of brilliant, unclassifiable work. The library of Kim Deitch graphic novels that’s been published over the last several years, beginning with 2002’s The Boulevard of Broken Dreams, is among the outstanding achievements in the comics field, and one of the few substantial bodies of work that lives up to the promise of the graphic novel as a format. Deitch seems to somehow top himself with every subsequent book. Reincarnation Stories is a masterpiece: one that may be his most accessible work in years, but one that is impossible to imagine as existing without the deep backstory — both personal and fictional — that precedes its creation. I recently wrote about his new book in the context of Deitch’s larger career for The Paris Review.

I’ve done a lot of work about Kim Deitch’s comics over the years. I curated a retrospective of his work at the Museum of Comics and Cartoon Art in 2008, and another exhibition of his work for the Formula Bula festival in France in 2013. I was also fortunate enough to contribute an introductory essay to his book The Search for Smilin’ Ed. But while I’ve conducted public conversations with Kim, I’d never actually sat down to interview him before. For this interview, I wanted to talk about the themes of and the process behind his latest book. I also wanted to talk about it more specifically within the immediate context of his most recent works, including the underrated illustrated novel The Amazing, Extraordinary and Absolutely True Adventures of Katherine Whaley.

Kim Deitch’s books are fictions that include autobiography and a broad range of real cultural history. And while they all stand alone, they are also part of a broader narrative tapestry that he has woven together over the course of his career. All of those elements came into play as Kim and I talked over an hour and a half in his Upper East Side apartment. At the time of this interview, Deitch had already made substantial progress on his next graphic novel, How I Make Comics. He was also preparing for a public conversation with the artist Nina Bunjevac, who is referred to in the conversation. I have pruned some of the more digressive tangents from our transcript while also lightly editing throughout for clarity, but this piece substantially represents the pleasurable and insightful experience of a long and casual conversation with Kim Deitch.

Bill Kartalopoulos: I think for a long time if anyone asked a reader of your comics who your main character is, they probably would have said Waldo. But I feel like at this point “Kim Deitch” is your main character. You appear a lot in the recent books.

Kim Deitch: Yeah, you know, I didn’t see that coming. It just kind of happened. Because in a way it was sort of a peeve with me that people are doing comics that are virtually blogs about, “Oh yeah, and then I went to the store, and I did this, and then I ran into Hillary…” But, you know, not only has that happened, but really now the main characters in my book are me and my wife Pam. And that’s gonna be even more so in the next book that I’m doing. But I think there’s good rhyme and reason to it. They’re fictional stories, or formats, used to tell other stories. And I don’t know, it just seemed to be working suddenly.

It’s interesting that in some ways it seems like it’s a reaction to some of the more autobiographical work you were reading.

Well, I wouldn’t say that exactly. It just that my relationship with Pam — she’s so close to the work I’m doing these days, it’s evolved into practically a collaboration at this point. She actually writes a piece in Reincarnation Stories. And it might hit stone collaboration at this point. She’s got her finger in it a lot more, and it’s been to my benefit because it’s working, in terms of generating material.

And that idea of generating material is interesting too. I’m wondering just in terms of telling stories or telling the kinds of stories you want to tell, if you think there’s something useful or at least attractive about those kinds of stories where the narrator is presenting everything as if it’s really true.

I don’t know, it’s just been a literary trope forever, and a literary trope I’ve stumbled over time and again. One of my hobbies has been reading nineteenth century novels, and they do it all the time. H. Rider Haggard sort of starts his books like, “I was sitting in my study, and suddenly this gaunt man was knocking at my window…” I don’t know, it’s just an interesting way to start a story, and to kind of palm it off as true is fun. I want to be a truthful person in this world, but it’s the thrill of being a pathological liar without being a pathological liar.

It was really interesting to think about Reincarnation Stories in the context of your last few books. This is your first new book of work since The Amazing, Extraordinary and Absolutely True Adventures of Katherine Whaley.

Right.

And it was interesting to think about this book in relation to that one. There are some obvious things about it that are really different, but then in re-reading that book I noticed some similarities and things that connected those two books. But the first super-obvious difference is that for your last couple of books, the Katherine Whaley book and Deitch’s Pictorama, you’ve been working in an illustrated prose style that you developed. So in a way, this is the first big book of full-on “comics…”

Yeah I’m back! (laughs)

(Bill laughs) … that you’ve made since Alias the Cat, in the sense of making a full-length story in the straightforward comics form.

I guess so. I went as far as I could go with that illustrated fiction, and god knows how much further I would have gone, but then, you know, Gary Groth is coming to me saying, “Kim, Kim, they want your comics!” And plus, you know, that was such an indulgence that they let me do Katherine Whaley, because, boy, they were already tired of me doing this illustrated prose thing. Well, I got it out of my system. I’m such a fan of the novel form, I just had to do one myself. Now I’ve done it.

And it’s not like I’m being dragged back, being pulled by my ear. I’m ready to be back in comics, and I’m ready to really embrace that experience again. It’s just, you go through different phases. I’m out of that phase. Now I’m back. Not only that, a sign of it is: I’m reading a lot of comics, which for a long time I wasn’t. I was just reading books. I’m totally addicted to the IDW Little Orphan Annie series, and went through a huge Simon and Kirby reading spree, which I think is about spent except I’ve still got Boys’ Ranch left.

I never thought you were out of comics because, first of all, you’ve made so many comics. And the illustrated fiction, or the format that you came up with, was so visual compared to the kind of illustrated novels that you’re talking about.

Well, that’s what I felt. I didn’t feel like Katherine Whaley really had less art than usual. You know? It was jam-packed with drawings and pictures, and even occasionally drifts into the comics when that seemed to be working. I was real proud of that book, and still am. I hope I can get some people to pay more attention to it. I don’t regret for one second doing it. It was really a fulfilling experience.

I think it’s a wonderful novel and I think one of the things that was impressive about it, too, is the way that just as a writer, you maintained this other person’s voice for that long.

Well, that amazed me too! I sort of spun out of a story I did in Deitch’s Pictorama where suddenly I’m in the female voice, first person singular, and how am I going to get out of this, and what does that say about me? I’d read a lot of female fiction for a while. I spent a whole year reading nothing but women’s fiction, and I think in a way this is sort of a response to that. Although, also, the voice in that one I did, “The Sunshine Girl,” even though it’s a female voice, one of the voices that I was sort of riffing off of was Huckleberry Finn, first person singular, which I re-read recently just before that. There was something very appealing about the first person chat of Huckleberry Finn.

You mentioned that you were doing a lot of comics reading. Is there a cause and effect? You were doing a lot of comics reading and it made you want to do more comics? Or you were interested in telling this story in the comics form, and at the same time you started looking at more comics because of that? Do you think there’s any kind of relationship between those two things?

I don’t know. There probably is. I tend to be influenced by everything that’s going on around me. In that case, I don’t know which came first, the chicken or the egg. I think the comics, I was sort of back in comics so I started looking at them. I just sort of got hooked back on comics. I was reading the complete serial adventures of Frank and Dick Merriwell, and when I finally finished that I needed a replacement for that, and my replacement was Little Orphan Annie. And what a great replacement. I mean, jeez, I’m just lost in that comic strip right now. That’s the big pleasure of my weekends. I get up on the weekend, I don’t have to work, I pull out the latest volume of Little Orphan Annie and read on that while I’m drinking coffee. Pleasure! Pure pleasure! And boy it’s getting good right now, the last days of 1939, volume eight.

I remember one time we visited together with a collector who was showing off story papers that he collected. And his story as I remember it was that he started out as a comic book collector, and he started working backwards through the cultural history, and then he got into the pulps, and then he got into the dime novels, and then he got into the story papers. So I kind of feel like you went from the dime novels to the comic strips. There probably is a strong connection between comic strip artists and the dime novels.

When you look at the dime novels, it’s like: there’s the comic book covers! The comic book covers were going along longer than the comic books! When I was a kid, about 1954, my uncle Don brought me a dime novel and I just looked at it and go, “What is this? This isn’t a comic book, but it looks like a comic book!” It just sort of planted the seed. So it’s something I had to go through. I’m over them now, because the bad news about dime novels is they’re mostly rottenly written. There’s some good stuff, but really: the good stuff is like Frank Merriwell, The James Boys Weekly, and really, the rest of it is pretty much shit warmed over. I mean, it has to be said. Sad, bad news. And being a hard-headed idiot, I had to really find that out the hard way (laughs) by reading a lot of it.

You show that in Reincarnation Stories, in the “Plot Robot” chapter, where you have yourself as a kid reading the dime novels and pulps that Wycliff A. Hill gives you, and even in the story you’re not super impressed…

He’s a real person, Wycliff A. Hill. Well, yeah, you know, I had a ball drawing those pages, where I’ve got pulps, dime novels, and everything. That was just a trip to do that and add some color to that sequence. Some of those are made up, some of them are copped from real dime novels and pulp magazines. I think all the comic book covers are made up, and the paperback novels. Paperback novels, that’s where I’m going next in terms of junk literature. Mickey Spillane-era and stuff, but also pocket book historical novels and stuff like that. There’s a lot of people that are heading in that direction. To me that’s probably gonna be the last frontier. And it’s funny when I compare notes with some of my comic book pals, including Art, a lot of people are looking now at paperbacks. I think there’s gonna be a big boom of interest in that.

Reading the Katherine Whaley book, even though it’s so different: you’re not really present as a character, it’s illustrated prose, even though it’s very heavily illustrated, it’s set in a more relatively narrow time period…

Yeah, a lifetime. A person’s lifetime.

Yeah, exactly. It’s a more self-contained book. But it was interesting to re-read it because I saw that there were these little notions that connected it to Reincarnation Stories. In particular, I didn’t remember that reincarnation is actually a theme that comes up in that book.

Oh yeah, right, OK. I hadn’t thought of it, but now that you mention it…

Because Varnay says that he believes that he and Katherine knew each other in a previous lifetime, and it comes up in a few other places as well. He thinks they’ll be together again in the future in more evolved form, something like that. And of course it comes up in A Shroud for Waldo, which is a big starting point for some of the stuff in Reincarnation Stories. Is that something that’s been a subject in your mind?

It’s gonna come up again in How I Make Comics, because basically how that one started is: Pam came up with a story idea. I like to overlap books, but I figured, you know, I’m getting on, I don’t have to do that this time. But then she came up with a storyline, and it was a reincarnation story! But it was good! And I just looked at her and I said: Let’s do it! And How I Make Comics kind of evolved around that. That story’ll be the payoff of a bunch of stuff that comes before it.

So, yeah, that is true. However, here’s the part that’s kind of odd, and this is coming up in talking to Nina Bunjevac, is that, OK, she’s really into all this mysticism, and I am too. But in fact, I don’t necessarily believe in reincarnation. Because: I don’t know! How am I supposed to know? I’m not gonna believe in anything I can’t know. I’ll accept that it’s a distinct possibility, or a possibility, but that’s as far as I can go. I don’t wanna commit myself. I wish I could be more of a crazed believer in stuff. Maybe you get some peace of mind out of it, but I can’t. I’ve tried all my life. I mean, I got saved on a street corner in New York City by some evangelist, but that didn’t take. I’ve tried all these things, but at heart it’s like, I’m a “show me” kind of guy. But on the other hand, it’s great story fodder.

I didn’t get a sense reading this how much you did or didn’t think about reincarnation outside of the context of working on this book…

I think about it, and sometimes I halfway convince myself there must be something to it. I presented the evidence in my life: I came up with it on my own, I had this weird, distinct feeling when I was four that I could remember a time when I wore glasses. That’s all true. But who knows what that all means? It might mean absolutely nothing. But it was enough to build a story on.

One of the thing’s that’s really striking is that you really seize on things if you think it’s material for a good story.

Yeah, that’s the bottom line. That’s the goal you’re looking for! I’m always looking for that goal. And I’ve figured out enough ways so that I manage to get a steady stream going when I need it.

One of the other things that comes up in a few of your books is Jesus Christ as a character. You mentioned getting saved on a street corner, and Jesus Christ keeps coming up as a character in your books…

He’s a great character! (laughs) I worked my way through the entire Bible and boy, is that tough going. But the real highlight, as far as I’m concerned, hands down, are the four gospels. Those are beautiful stories, and just well written. They could have thrown another one out of apocrypha in there and I wouldn’t have complained, because it’s just moving, and it’s also just fabulous literature. Some of our earliest fabulous literature that I happen to know about. There’s probably other stuff. It’s a wonderful character. Jesus Christ presents this wonderful model for living, which is great if you could actually do it. It’s a little tough in the actual execution. I was always fascinated by the fact that Jefferson, who I guess was pretty much of an agnostic but moved by that thing, made his own Bible by cutting out all of the supernatural stuff, you know? I’ve never read it. And he did it for the same reason. He said, “I can’t be like this, but to aspire to it isn’t such a terrible thing. And here’s what I think is the real meat and potatoes of it.”

If you think of it just as: there was this preacher who had these ideas, who was a good example, versus all of the mythology that surrounds it, you can separate out those two things and think of it as a philosophy for living, versus a metaphysical description of the world.

And who knows, maybe there’s something to that stuff, but I tend to be sort of skeptical. Of course there’s this gospel of Thomas which is kind of interesting. It doesn’t have a storyline, it’s just lots of quotes from Jesus, and it seems to be authentic. And that’s sort of interesting because — I haven’t read it, but from what they tell me, there’s talk about reincarnation in there. Which is obviously taken out of the official story. So that’s sort of intriguing. Who knows what to make of that.

And that’s similar to the subject of Katherine Whaley, too. At the heart of it there’s this essentially lost testament of Jesus that’s been engraved on ceramic tumblers…

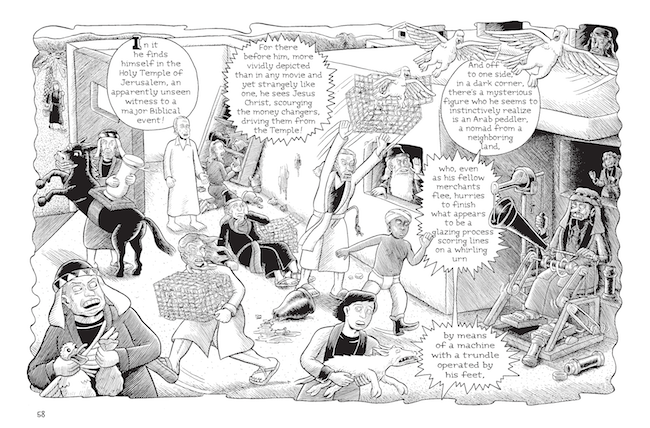

(Kim laughs) Yeah, right! That was just a great gimmick. You know, I remember I was sitting around with Gary Groth one time at dinner, and Gary Panter was there, too. And Gary just, out of nowhere — the conversation was lulling at the other end of the table — he turned to me and he said, “Kim! What’s the best story idea you have that you haven’t used yet?” What an impertinent question. But you know, I had an answer! Which was this whole idea that Jesus Christ could have been throwing the money changers out of the temple, and someone scoring something on the side of a pot could have accidentally been recording it. And I had that little thing around, and I didn’t know what to do with it! And then one day, I found a home for it, and the home for it was the Katherine Whaley book. And that’s a funny thing I’m proud of. Just about every crackpot, stupid notion I have, I seem to have a pretty good, methodical way of getting around to it sooner or later. Something is sifting in the back of my head, utilizing these things.

And of course there’s some real truth to that. You know, you go on YouTube, you can find these recordings that exist from before they were recording. Some guy had some kind of a graphometer, he was just looking at the vibrations of the human voice. And nobody meant to do anything with them, but now in the computer age they’ve taken some of these and they’ve got a human voice of a woman singing, circa about 1858, 1860. You can hear it yourself, she’s singing a little bit of a French folk song. And also there’s people hitting tuning forks, from back in 1859 and stuff. So there was some actual, real precedent to that. Who knows what other accidental records might be out there? It just seems like it could have happened. I’m not so sure I didn’t pick this idea up from somebody else somewhere, but I couldn’t tell you where if I did. But you know, I have a spongey mind. Could be.

There’s an idea that comes up in a few of your books, that things that are mystical or magical or unexplained are maybe just science that humanity hasn’t caught up with yet.

Yeah, Waldo says, “Yeah, the supernatural is just science we haven’t caught up with yet.” Yeah, me and Nina are talking about that right now, too. I think there might be something in that, as well.

Certainly recording a voice two-thousand years ago would have seemed like magic.

There’s this Fox Movietone movie about Conan Doyle talking about his belief in the supernatural. At some point, if you had shown somebody that film in maybe 1850 or something, they would say: “There it is! That is proof of life after death!” It isn’t proof of life after death, but we can actually see dead people. There’s Conan Doyle, sitting there looking straight at us in 1927, talking about this stuff. It does seem like there’s this weird correlation between truth and fiction there.

In your books, the stuff that seems sort of mystical — you don’t exactly give it a scientific explanation, necessarily, but you give it a science-fictional explanation. So it might be aliens, or things on other planets or something like that. You take that Jesus character, and Jehovah, the god above him, and they seem less like mystical beings than just the overlords of some planet. (laughs)

Petty tyrants, yeah. It’s just fun to come up with crackpot logical explanations for the illogical. I thought I got pretty far out on a limb with some of that stuff.

It makes me think of that “Ancient Aliens” stuff…

I was addicted to that show for a while, then I got kind of sick of it. Three or four years running, I was right there every Friday night.

In this book there’s reincarnation, there are aliens, and the aliens are connected to this other idea that is also in the Katherine Whaley book, which is that maybe humans aren’t the endpoint of evolution, and maybe animals are going to evolve to become the next dominant species.

Yeah, that seems fun to me. I really like this new evolved cat character, Boxer, I’ve got. I’m doing a little reprise of him in the next book. But I just feel there’s more I can do with him. Yeah, but what if all of the animals became evolved versions of themselves?

You have the evolved beavers in the previous book, and the evolved cats in this one.

Yeah. Yeah. Boxer, and he’s got a girlfriend, unnamed. That’s a character I’m definitely not done with. I just like the way he looks in general, anyway.

It reminds me a little bit of the cat comics you did for the Little Lit books.

Yeah, it does. Yeah. Well, you know, I loved working on that story, “These Cats Today.” I was on fire when I did that one. It was fun. Yeah, so there’s definite influence. I’m gonna be pulling back some of that with this new Boxer character. Plus it paid off that story, “Kitten on the Keys,” so well. It just sort of seems like this dead-ass story, and: no! No! You turn the page — wait a minute? How could he be this big cat? We just saw him moody about how he was never gonna be big. I don’t know, I love that. Just love that. I also like the fact that “Who Was Spain?” is only just marginally about Spain. It just sort of takes off and plays with the rest of the book. Boxer even does a little crit of Reincarnation Stories at a certain point. I was cracking up over my own material for a while there.

I wanted to ask you about those appendices. The Spain story is a little bit like the Jack Hoxie story, where you don’t have to give too much in the appendix because you’ve already covered it in the book.

Yeah, right. All that stuff in that Jack Hoxie story, that is all true stuff. I loved doing that story. But yeah, the appendix, it’s like: I couldn’t stop. I was having too much fun with this book. I did the appendix. But actually, I’m so glad because, for me, some of my favorite parts are in the appendix, including one I didn’t even write myself, which Pam wrote. I just love all those. I wouldn’t have not done those for the world!

I remember when you were working on the book, it seemed like I talked to you a few times in a row, and you thought you were almost done but then you had an idea for another appendix, then you had another idea for another appendix…

That always happens to me once I’ve got my ball of steam going. But usually it’s sound, and it pays off with more good stuff. Because by that time I’m so warmed up, I feel like: “Nothing’s gonna stop me now!” (laughs) It’s a shame to get over that feeling, but boy, when it’s going, it’s just like the greatest feeling in the world.

You mentioned before you usually have a practice of trying to have something ready to get started on when you’re finishing a book.

Yeah.

And as you were bringing Reincarnation Stories to a close, you kept coming up with these appendices to add to it. Was there ever a question as to whether you should include something as an appendix to this book, or maybe it could have been a good starting point for the next book instead?

That happens. In this book, not really, no. When I suddenly have Jay Lynch going, “Um Tut Fuck You!” I think, “Welp, it’s time to go! (laughs) That’s enough of this!” But by that time I had stuff going. But in this next one, actually, you know, while I’ve been working on getting that one together, I came up with another nice story. And that was definitely something that was going to be outside of How I Make Comics. But Pam said, “Well, you know, maybe that should be in How I Make Comics?” And she talked me into it. So there’s gonna be an appendix in How I Make Comics, and there’s going to be at least one thing in that appendix, and that will probably be this other goofy storyline that just came to me. All my story ideas, they start under that piece of plexiglass. (Deitch points to his desk) Any time some idea comes to me, I write it down and I stick it under there. And the first story for How I Make Comics was one of those.

And when you can get to that nice place — and I’ve been lucky so far of being able to just come up with them, unbidden. Stories unbidden are often the best ones. And I got a story unbidden for the appendix of How I Make Comics. It takes place in the Bronx on Riverside Drive. I still have to work out some of the interior data of that story, but I’ve got a great set-up. And it’s completely different from anything else I’ve been doing. It’s different characters. It’s gonna be great. I hope. You know, all I have to do is last long enough to do it.

Can you talk about getting started on Reincarnation Stories? Like we were saying before, the thing that you did right before this was finish the Katherine Whaley book. And you were saying there’s some stuff that’s true, that you did remember, like having glasses when you were four years old. And the other thing that’s true that I remember you talking to me about is that you really did have this retinal injury.

Oh yeah. That was a bitch. While I’m sitting there with my head down, I was starting to generate some seminal material for this book. But the real place where I started that book was the story about the monkeys, “Shrine of the Monkey God.” That was the very first story I did. And that was just this loose story I had in mind. I didn’t know exactly where to place it. But somehow it just fit perfectly into this book.

Was it originally a “reincarnation story,” or just a story about, “What’s the backstory of one of these Museum of Natural History dioramas?”

Something like that, the fascination with the dioramas. You know what it really was, it was that one diorama of all the white-mantled colobus monkeys. I was just looking at them and thinking, “Jesus Christ, man, they slaughtered this whole village just for that fucking little diorama! Cocksuckers.” Actually it turned out it was more of a collection. Some of those stuffed monkeys went back quite far, and then they fitted them into this thing. They weren’t necessarily all the same generation of monkeys that knew each other. It sort of spoils everything to hear that, but when I started looking in Google Images I was starting to discover that.

And there’s just something so strange and antiquated about those old dioramas. It’s just like a link to our childhood, because we can all remember going and seeing those things when we barely knew what the fuck was going on in the world. And definitely me. We definitely went there on school trips and other trips, at least as early, probably, as 1951. I put the story in ’52 because that’s when I was in second grade. That’s my real second grade teacher there, Mrs. Murphy. That’s where Reincarnation Stories started, with “The Shrine of the Monkey God.”

And then the retinal injury became a way to frame the beginning…?

I might have had the retinal injury before I did “Shrine of the Monkey God.” I was taking notes and stuff, because I was getting stir crazy. You can only sit there and watch movies so long. You want to do something else.

I would guess that for a visual artist having any kind of eye injury must be stressful and frightening.

It was pretty bad. Yeah, I was frightened. I thought, “Shit, I’m through.” I could have probably gone on, but you know, brush inking, you really need that depth perception for that. So that’s going out the window. But this guy brought me back. It turns out this is a routine operation of a sort. I had actually heard of a friend of Pam’s having it before this hit me. The weird part is they didn’t know why this happened. And I asked the guy, “Well, is this gonna happen to me again?” He said, “Ten percent chance!” And dismissed me. “Oh, OK.” It’s been a while. So far, so good.

Something’s always getting me. Shit, I’ve had problems with my drawing hand recently. I had to go to Pam’s personal trainer, stop doing push-ups, start using these rubber things instead. And it’s so far, so good. I just came off of a bunch of really intense inking, and it seems to be working OK. So, just keep doing it until I can’t keep doing it. Or I’ll go nuts, the day when I can’t be doing it. I probably wouldn’t last long, far after that. I just don’t think so. But anyway, I’m still doing it. That’s the good news. (laughs)

One thing that is nice about reading your books is that I feel like I always get a look at things that you’re interested in that you include in the books. One of the things that comes through in Reincarnation Stories is that it seems like you were looking at a lot of silent westerns at some point.

Always. Every one I can get my hands on, all the time. It’s a great form of personal entertainment for me. Early sound, too. And even later sound. Even Roy Rogers and Gene Autry. I love them, I just love them. Is that a guilty pleasure? I don’t know. I think Westerns at their best are kind of a bastard art form. I think it’s the heart of the movies, really. That’s where the movies started. Some of our greatest directors: John Ford came out of the westerns and never quite let them go. William Wyler started out in the westerns. You’d be amazed how many guys started out in those. And there was great art in them right from the get-go. William S. Hart was a Victorian guy. He came of age before the turn of the twentieth century. He was making great movies! You look at those now? They’re terrific! They really hold up. I love ’em. I like all the eras of it, too. I like Randolph Scott, man. John Wayne when he isn’t full of shit. There’s a lot of them where he isn’t: all these John Ford movies he appeared in. They’ve been showing Rio Grande on the Western Channel from about 1950, directed by Ford, with John Wayne: that’s a beautiful movie! John Ford wanted to make The Quiet Man. He went to the head of Republic, trying to sell this movie. He said, “Well, all right, I’ll let you make it, but you’ve got to make me a western with the same stars first.” And so he made Rio Grande. It’s so much better than The Quiet Man. I mean, The Quiet Man seems like kind of a jivey, full of shit, lovely Irish bullshit, whereas Rio Grande is like: “Woah! What a great movie!” Just every shot is just picturesque and wonderful, John Wayne never looked better. So go figure.

You see a lot of stuff. You were talking about reading dime novels, and watching these movies, and reading comic strips and all. I know you’re a big aficionado of a lot of culture, and you spend a lot of time tracking stuff down, too.

I’m a big fan of popular culture, and even unpopular culture.

But you put in the time. Like you were saying, you don’t just read one dime novel to see what it’s about. You read a lot of them until you’ve really exhausted it.

It’s like our hobbies. Reading nineteenth century legit novels is a hobby of mine. I’ve just about exhausted every important novel of the nineteenth century in the English language. But now I’m switching over to the French. The Mysteries of Paris by Eugene Sue is next up, then I’m going to pick up what Dumas I haven’t read yet, what Victor Hugo I haven’t read yet, all of Émile Zola. Because I’ve read a couple of his classics but not recently. That’s where I’m going next with nineteenth century novels. The only reason I resisted on the French: it’s not that they’re any less good, it’s just that all of a sudden you’re dealing with translations.

You don’t know if you’re reading a good one.

Yeah. Just to read all of the Dumas Three Musketeers books, of which there are five, I ended up having to get different translations to compare and contrast. And I was a little shocked at how much variance was going on.

When you read that stuff, in addition to getting pleasure out of it, do you find storytelling techniques or story ideas that end up working their way into your books?

I suppose. I remember never buying the book of The Count of Monte Cristo, but when I was about ten seeing the movie with Robert Donat on TV. And I remember going, “Wow! Now there’s a plot!” (laughs) It’s just this archetypal revenge plot. God, how many times has that been imitated, or variations imitations of that? Incredible.

Even with something like the Western, if you’re watching a lot of stuff in that genre, what is it about a figure like Buck Jones or Jack Hoxie that distinguishes them in such a way that they actually end up in your work, as opposed to, say, John Wayne or any of the hundreds of others you might see?

Well, those are just two stand-outs. I go into it in “Who Was Buck Jones?” The guy could act. Ford directed some of his. There’s a non-western directed by Frank Borzage, and it’s really good. He could have crossed over. I don’t think he wanted to, I think he was too committed to the western genre. And Jack Hoxie, I don’t know, they’re just kind of good old, good natured westerns. They stood out, he had good directors, and there was just sort of an interesting unaffected thing about him. I started looking into his history and seeing, “Oh, he accidentally killed his brother,” and stuff. You can see why he wasn’t quite — so many of these western stars were really, like, guys out on a spree, like Tom Mix and plenty of other ones. They just wore out on high living and stuff. But those two guys: Buck Jones was pretty level headed. He was married to this one woman. The worst thing you could say about him: he got a little cranky about singing cowboys and he kept his daughter on a pretty short leash, but he seemed like a pretty good person, and that sort of comes through in his movies. And Jack Hoxie, too, he just seems like this curious, level-headed guy. He became a star like many of them, out of wild west shows. He was a star for a while, he sort of left, and then he was just sort of working small time shows and stuff. It didn’t seem like it killed him. It just seemed like, “OK, now I’m doing this.” I have him talk about his pet dog and his pet horse. He really loved these animals he worked with. He just seemed like a real genuine guy. It just appealed to me. And the first thing you know, I’m making up this lying story about knowing him.

The one thing that comes close in my life that actually happened like that is when I was seven years old in 1951, me and Simon, we went to the Thanksgiving Day parade. We got there a little early and before it started we looked over: and there was Hopalong Cassidy, standing next to his horse, ready, waiting to get into the parade. And we were so little, we just looked at him: “Hoppy!” And went running over! And he was nice as could be. “Hi, kids, howya doin’?” Just like it was the most appropriate thing in the world. And then our folks came over to break it up, and he shook hands with them and was nice to them. And so I figured, well, you know, turns out that Bill Boyd’s first western film was a silent film that Jack Hoxie was in, so I figured, well, when I shook hands with Hopalong Cassidy, I shook the hand that shook the hand of Jack Hoxie. So, go figure. Crackpot to the end.

There are a lot of stories in this book. One of the things that’s nice about the reincarnation framework is that it’s a story that can contain other stories somehow.

It seemed to work. And it sort of seems like something was guiding me along with it, too. I could almost pull a mystical thing out of that, but I don’t know what it really means. It probably just means that my mind was ready to do this, because every time I would be done with one thing, something in the back of my head was, “Come on now, now we’re going to do this, now we’re going to do that.” And some of the challenges to overcome seemed insurmountable, but every time I hit ’em I was up to it. So it was very fulfilling in that way. And I’m having the same thing now with this one. I’m thinking, OK, I’m doing the opening stories of this How I Make Comics. I know I’ve got some stories coming up that are gonna be a bitch to draw. You know, I’ve got the basic framework, but there’s a lot I haven’t figured out. And on some level I’m terrified about that. But what keeps me going is I’ve got the precedent. You know? “Well, I did this and this, so I can do that.” That’s kind of the magic that keeps it going. The logical magic, if you’re down to cases.

Some of the things you’re talking about are also the subject, it sounds like, of How I Make Comics. When you talk about keeping your confidence up because you know you’ve done this kind of thing before, that’s also the kind of thing that I think you’re going to be talking about in the next book, in a way, right?

In a way. In a way it’s a big fraud, because there’s very little… I don’t know, maybe there’ll be an essay at the end where I really get down to some cases and tell some of my secrets about how it’s done. But really How I Make Comics is a big fake. It’s just an excuse to have a nice set-up to tell a bunch of new stories. That’s the real truth about that. It started out: I’m going to do a book, I’ve learned a lot of stuff, I’m gonna share it, I’m gonna do a how-to book.

But you know what killed it? I’m not gonna mention any names, but there’s a colleague of mine out there in the world who’s been in a terrible slump for a long time. And I just said to him, “Don’t worry! I’ve got all kinds of ways to get out of slumps and stay out of slumps, and I’m gonna get you up and running. I’m about to do a book about this, so you just put yourself in my hands. And we’re gonna have something.” And so, he did. And I failed: miserably! It didn’t work!

I said, “Well, yeah, you’ve worked on a lot of stuff for yourself. But it does not follow then that you’re also a great teacher and are going to be able to pass this stuff on to somebody else. And here’s the proof of it.” So I said, “OK, that does it. I’m not gonna do this book.” But eventually when I picked it up: OK, I’m gonna do a book that’s gonna be an alleged how-to book. But it’s not really gonna be a how-to book, because I’m not really qualified.

Well that book is about education in the same way this one is about reincarnation. (laughs)

I’ve done some teaching and stuff and I like it. But my best strength as a teacher is that I get with the kids, I like the kids, and I develop a nice relationship with them. But that doesn’t mean that I’m a good teacher. That just means that I’ve got lots of good stories that they like to hear me tell. I can entertain them.

Teaching’s a little different I think, because sometimes just taking the students seriously, or just sharing experience with them…

I can do that. I can take them seriously…

… gives them a lot of grist for the mill. Even for them just to be in a position with someone who has experience, who’s being straight with them can give them a lot to think about, and can also get them started thinking, even on a really basic level: “Well, I agree with what he’s saying here, but I don’t agree with what he’s saying there.” In a way they’re just in the room with you and on the same page with you.

Well they get that from me. I respect kids. I respect youth. So they’re always going to get more than an even break from me. More than a lot of people. I’m never gonna take this haughty look-down attitude about it with them. And that’s probably a good thing and a bad thing at the same time in terms of being a good teacher.

One thing you do in different ways in a lot of your books — and you also do it in Reincarnation Stories — is you’ll often tell a story more than once from different perspectives, or you tell different versions of the same story. So in this one I’m thinking particularly of the “Hidden Range” story, where we get a few different versions of it, and even “Young Avatar,” we get a couple of versions. It reminded me, too, of Alias the Cat, where we see the comic strip, then we read the newspaper articles, then we hear an oral history from somebody who witnessed the events, and the reader gets these different versions to put together. “Hidden Range” seems like the main one where you do it in this book, where the reader reads what you present as a visualization of a screenplay, then we hear the legend that it’s based on from the Jack Hoxie character…

Yeah. That’s one of my favorite parts of the book, when Jack goes, “Yeah, there’s one part about the story that wasn’t in that…” And he tells the migration story to this little, small moon…

That’s a beautiful spread, too…

Boy, I just loved that. I thought, “Oh, I’m in the gold now!”

And then later Waldo tells a slightly different version, giving it a little more background and bringing it a little more down to earth. I love that, and I think for the reader it’s a very specific example of something that you do in other ways, too, where it puts the reader in the position of putting the pieces together…

Yeah, it’s like pseudo-folklore. It’s sort of like the four gospels. You get slightly different variations on that story, four times. That was sort of brilliant. I mean, it was sort of accidentally brilliant. That’s been around for a long time.

What attracts you to doing that kind of thing? To telling the same story, and then telling different versions of it? Why do you think that works for your books?

I don’t know, it’s just something I do. It’s not like I set out — I don’t think I’ve ever set out to do that. It just happens. It just happens.

Why do you think it works for you as a reader, when you say it’s brilliant to read the four gospels?

It seems more real. OK, here’s the story again, but, oh, what’s this woman taken in adultery? We’ve never heard that one before. It turns out that while it’s maybe the most beautiful part of the story, it’s probably also most likely to be the most spurious part. All the scholars look at that, and say, “Nah. Nice story, but: never happened.” Boy, that was the first story — even before I read the four gospels — that attracted me to the Jesus legend, was the woman taken in adultery. I think I encountered it in Oscar Wilde’s essay “De Profundis,” and I just thought: Woah, there’s a story. Woah. That was the key to my being more interested in all that.

It does make the whole thing seem a little bit more real somehow. Which is almost counter-intuitive, because it’s not presenting a fake factual account, but presenting a bunch of different versions of the same thing. In a way it reminds me of doing research, even if it’s just personal research for fun, or if I have to research something for a professional reason, eventually…

You come up with a new angle…

Yeah, and eventually, sooner or later, you’re gonna hit on different versions of the same story, and you’re going to have to make some choices about what you might believe or not believe. (laughs)

Right.

I would assume that with the kind of stuff that you’ve been interested in — I think film history is a good example, but even comics history is a good example. I was recently doing some research into the “golden age” of comics, and there are a million interviews in Alter Ego magazine with guys who were drawing comics in the ’40s and ’50s. But you’d have a real hard time massaging all those accounts together into a coherent story, I think.

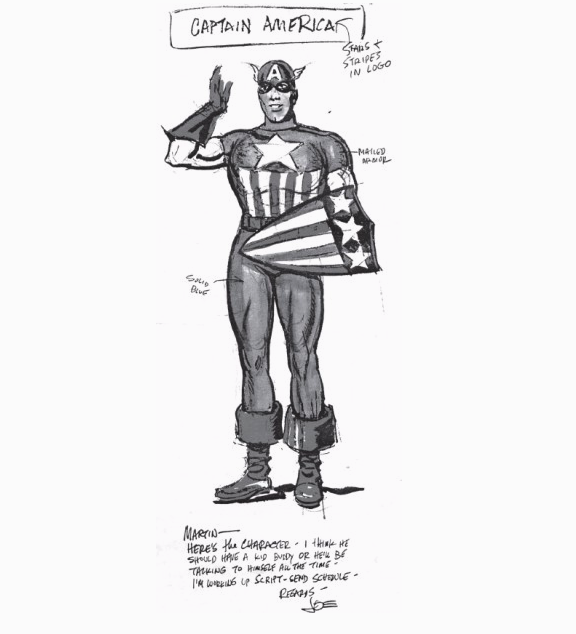

And when I was getting into Simon and Kirby at a certain point, talking about it on Facebook, Jeet Heer chimes in, going: “We’ll probably never really know why Simon and Kirby broke up.” Yeah, I think there was a fight in there that we’ve never heard about, that Jack chose not to talk about. Because I read Joe Simon’s autobiography on the recommendation of Art Spiegelman. And it turns out that while that book is a good read, there’s a lot of bullshit in it. He’s a big bullshit artist. But he does it well. It’s a book that works. I enjoyed it. But boy, then one of my friends came down on me: “He was such a schmuck! You believed that?” And I started thinking back. Right after Kirby was dead, suddenly Joe Simon comes up with this picture of Captain American that he allegedly drew, and there’s a little note on it saying, “Martin, I think this might be…” Come on, that’s bullshit! And we could all tell that was bullshit, going out of the gate. And I sort of conveniently forgot about it. Suddenly Kirby wasn’t around to dispute it, so let it fly!

Reincarnation Stories is a full-length, graphic novel, with pretty much wall-to-wall comics pages, that you’ve done after doing a couple of books in an illustrated text form. But this book has a lot of approaches in it. There’s a way of making comics that is maybe your main approach, maybe the most typical way that you draw them now, but there are some sequences that feel more like the illustrated prose, like the first “Hidden Range” story. It’s presented as if it’s a visualization of a screenplay, so it’s super heavily narrated, there are no word balloons as far as I remember…

No, there aren’t, right…

… because you’re reading a visualization of a silent film. And in the “If It’s Weird It Works” section, you have this great two-page spread…

Yeah, that was fun…

… where it looks like you’re re-creating the visual world of your underground comix in the East Village Other. And you have those great full-page images, too, that remind me of the drawings you do for Pam.

Yeah. They inspired the color section in Reincarnation Stories. Also, in the Spain story, there’s one page where Spain is talking the boss out of docking our pay. The story is a crock, but that whole page is absolutely true, visualized exactly the way it happened —that I saw happen — all the things that Joel Fabricant is saying. He’s going, “I don’t know about you, Spain, but my God is the dollar!” It really happened, just like that. While part of me was going, “Oh shit, we’re catching it, we’re gonna get docked,” I was also thinking, “That I could be sitting here, listening to this folklore on the hoof like this is a miracle!” (laughs)

And in that section you reprint the two pages of jam comics that you and Spain made. I thought that was great to see…

Yeah. It’s funny how that worked out. In reality, we were both kind of fucking around that week, and Spain just suddenly said, “Hey, why don’t we do a jam?” And I was just, “Well, it’s gonna save my ass, shit yeah, let’s do a jam!” (laughs) That’s all it really was. But we were really really late, because we started really really late on it! (laughs)

I think it’s great that you included it though, because you could have told that story without reprinting those pages.

Well, again, this sort of bogus vindication and proof. It wasn’t true, but: “Well, yeah! There it is! What do you want? There’s the strip they did! I’ll buy that!” (laughs) And then I follow it up with an absolutely true anecdote about us coming in, turning it in. That’s gotta have the ring of truth, because goddammit, it is the truth!

Did you have any qualms about showing this kind of work that you made when you were so young?

Yeah, I did. God, my drawing is so shitty compared to Spain there. I’m really showing just how much I was earning while I was learning. If ever you wanted to see it, there it is baby! (laughs)

Just in one book, someone can see all these different ways you have of making visual stories, and how much you’ve evolved since the time that you started at the East Village Other.

It’s sort of a referendum, along with being other things. Yeah, that has occurred to me.

I also liked the “Young Avatar” pages that are in there, too, especially the ones where Jesus, Judas and Mary are children. I felt like you were channeling a sort of Little Lulu, Richie Rich kind of style of comics-making.

Yeah, it was sort of like that, yeah, the rollicking adventures. Well, you know, there’s all this apocrypha of Jesus as a cranky kid. I’ve got a book of apocrypha. All those stories about killing a kid and bringing him back to life, they’re genuine apocrypha that didn’t make it into the Bible.

Can you talk a little bit about these full color images? These seem like this wonderful fantasy of you and Pam buying your building…

Well that really did come out of those annual pictures I make for Pam. It just started out, she said, “I want you to make me a Valentine!” So I made her something. And just little by little, they turned into big, elaborate drawings. They usually take about a week to ten days to do these days. But they have a life of their own.

And those are full color, colored-pencil drawings?

Yeah, colored-pencil drawings, but inked. So I really was trying to get some of the flavor of those. And I just wanted to sort of take Pam’s trip there. “Well, what it could be like if there was this crazy museum, if we owned this place? What would it be like? Let’s see it, buddy!” And why not do it in color? That’s just part of just how being with Pam inspires me. I just wanted to show her off good, and her interests generate good material for me. It comes out here, it comes out in that crazy story I got her to write later on in the book. Because that really happened. Everything she said in that story about us going to the class in past-life regression, it’s all true. And boy, I didn’t expect — I was done with that, nothing happened. And then she comes up with, “Oh yeah, I was in Indian boy, it was back in the eighteen—…”

“Oh really?!” Even if she’s putting us on, and I don’t think she is, it doesn’t even matter. It’s a good yarn, that’s it! You gotta write this down! And then of course I had to sell that to Gary Groth. But he went for it. I explained, look, it’s germane to the book. Just go with me on this. (laughs)

When she says that you were interested in going to that past-life regression class because you were working on a story, was it specifically for this book?

When she says that you were interested in going to that past-life regression class because you were working on a story, was it specifically for this book?

Yeah. The funny part about this book is this: right after I finished Boulevard of Broken Dreams and I was working with Chip Kidd, we were on the phone. It turns out it was the day before September 11th. So Chip’s going, “Well Kim, what are you gonna do next?” And I said, “Well, actually I think I’m going to do a book about reincarnation.” And he goes, “Oh yeah, that sounds interesting.” And then the next day 9/11 happened, and everything got kind of crazy. And they sent me out on a book tour for Boulevard of Broken Dreams. While I was on the book tour I got the idea for Alias the Cat, and I started working on it and I just sort of forgot. So I often wonder: “Well, I didn’t have any fucking reincarnation story! If everything had gone according to plan, I wonder what that book would have been?” Because it wouldn’t have been necessarily this book. It would have been a book that might have had some similarities. I’m glad it didn’t happen then because this seasoned in the wood awhile, and it worked out great. Beyond my wildest dreams great, this book worked out. I’m so fucking thrilled how it came out. I can’t even tell you. I can’t even tell you.

It’s definitely your biggest book…

It seems to be…

… and in some ways I think your most complicated, too, just because there are so many different stories…

Well, I was trying to keep it simple, yeah, but I seem to have fallen into the morass of complexities, in spite of myself.

But I mean that in a good way…

Yeah, I know…

… in the sense that it makes it fun to read, because there’s so much stuff in there.

I hope so. I hope so. It seems like it’s clear to me. Some of the early reviews I’ve been seeing make me kind of wonder. “Oh, he’s off on this, and he’s telling you that…” Okay, well, it’s not for everybody. All right.

I feel like what the complexity does is it makes it all feel more real. Reading three different versions, for example, of the “Hidden Range” story: in a weird way, I don’t remember any one of them very specifically, but I remember just the general shape and feeling of the story, and it becomes more like a memory to me, somehow.

Yeah, I know after a while… I get swept into it too. “And then Jack told me this…” No he didn’t! (laughs)

You have to remind yourself that you didn’t meet Jack Hoxie when you were ten years old…

No, I never met him. I should’ve, but I didn’t.

I was amazed that the story about him accidentally killing his brother was true.

Absolutely true. And also working with Pavlova, in that early movie. They found that movie. It’s kind of a dud. But yeah, he’s got a big part in it. They were fast friends. He saved her from falling while they were on the set one day. He went to grab her, prevented her fall, and she slapped his face. But then she realized: “Oh, he saved me from having an accident here.” That formed a bond. And they were really good friends throughout the filming of that film. “Jack, you know, you’re going to be in all my movies now.” That one was a big flop, so that was the end of it. But you know, he was really proud of that and he never stopped talking about it. “Yes, I’ve worked with Pavlova!” He’d have to tell all of these Western kooks who Pavlova was!

Reincarnation has come up in a couple of your other books, and the big one that this book really connects to is A Shroud for Waldo. And you even depict some of those same events again.

Yeah. I was studying A Shroud for Waldo while I was doing “Young Avatar.” In fact, I was even serializing it once a week on my Facebook page. I went through the whole story, if you wanted to follow it. I gave it away. If you couldn’t afford an old out of print copy, you could read it every week on my page for, I don’t know, sixty weeks? Yeah, I think it was sixty.

So you started thinking about this book, and did it occur to you that, “Oh, I’ve already done something on reincarnation and I need to bring it into this book?” How did that happen, that you came to be studying that book and referring to it in this book?

I just know that I alluded to this whole idea that he was the reincarnation of Judas Iscariot in that story. So if I’m going to have him tell that story, I’d better be up on how it went down there, so I don’t stumble over myself. Also, Sammy Harkham had been telling me: “Oh, I really love that Shroud for Waldo, I want to do something with it.” “Oh jeez, maybe I ought to take a look at it anyway.” It’s sort of a fun thing, it’s sort of a tight story. I was going, you know, Waldo’s going to cover that material again. I wanted to make sure that I didn’t mess up and contradict myself. But also, I expanded on it. I had more to say about that. Finally we’re really getting Waldo’s big story in this book. But I’m very proud of the fact that a good hundred pages go by before he even shows up.

Even though he’s in it, it doesn’t feel like a Waldo book to me…

No, it isn’t, although there’s practically a Waldo book in it. I didn’t want to just do that. I don’t want to overuse that character. I might be through with him now, but he’ll probably come back. Well, actually, that’s not true because the sequence I’m doing right now, Waldo’s in it.

Did you have an idea pretty early on working on Reincarnation Stories that your past lives were going to connect to Waldo’s past lives?

Yeah, I did. I can’t exactly say why at this point. I like the way it all worked out, in that I’m a character, but I’m not any really important character. I’m just this jerk that Jesus kills for fun and then brings back to life, and then I’m never quite the same. And Waldo makes a big thing about that: “Yeah, you know, you were always kind of slow. Maybe this is it.” Although he’s already talked about how when we came out of the slime together as prehistoric, primordial whatevers, even then I was dragging. And then it took me forever to get out of the monkeys, and he was waiting for me to hit humanity. “You were always kind of slow.”

I think in a way I was sort of echoing my relationship with Simon Deitch, who really, at heart, was probably smarter than me in his prime. But he didn’t know what to do with it. Well I knew what to do with it: I collaborated with him for as long as he was worth collaborating with.

It’s funny, that idea of knowing what to do with it. There’s a point in this book where you depict yourself talking to Waldo about Jesus. And Waldo’s saying, “Yeah, I still see Jesus in the park, he’s got this magical bag of breadcrumbs that never empties, he’s feeding the pigeons…”

I liked that scene, too! “As far as I’m concerned, he’s another nice guy, you know what he’s going to say…” Oh, I loved that scene. Plus the recreation of Central Park…

That was beautiful…

… boy, that was a lot of work, that was a lot of work, but I’m really proud of that!

What you were saying about not knowing what to do with it, that’s like what Waldo says about Jesus: he’s still got it, he can still make the breadcrumbs appear, he just doesn’t know what to do with it…

Doesn’t know what to do with it…

Yeah, and one of the big things that comes through in the book, especially at the end, before the appendices, is that you have to do good in the world, whatever that means.

And then we have a Platonic discussion of “what is good.” And that comes from reading Plato. Define your terms. That’s where I got that.

You’re so motivated to make these comics. I feel like even if it didn’t say that explicitly, that’s this implicit statement, that you have to keep doing this stuff. Certainly something keeps you motivated.

Yeah, and plus it’s just such an old cliche in superhero comics: “And remember my son, you must only use your powers for good!” Old man Shazam tells that to Captain Marvel. “Yes sire!” I’m gonna go into that a little bit in this next book, too. I’m going to have a story that takes place during the Golden Age of comics. And this guy becomes a superhero in life and is inspired by the comics, and also by some other stuff. And that’ll be a good story. And it’s gonna be called “The Guardian Angel.”

One of the things that you do in this book is that you’ve got all of these past lives, and you tell the stories of some of them, and you show a lot more than you tell.

Right. None of them look particularly noteworthy.

In the end you break the whole cycle of reincarnation in the book…

Yeah, that’s my argument with Boxer. He’s all for science, and I’m going, “Well yeah, but, now here I am…” Complaining, because I’ve got this nice life they’ve set me up with, and me and Pam are still together in three hundred years. But you know, I always was a complainer. I have a wonderful life and I’ve been remarkably blessed, and I complain a lot. That’s just me. I’m a motherfucker, what are you gonna do.

But I think in the end you depict yourself complaining, so you know what you’re doing. You’re self aware about it.

Yeah. I’m having a go at me.

And also I feel like the book, by depicting it, makes the argument that the best future would be for you and Pam to continue forever. (laughs)

Oh, I would love that. I would love that. I am very fortunate in my marriage. And it’s given me tremendous happiness. And yeah, I’d love to have it go on forever.

And be surrounded by talking cats.

Yeah, why not? As long as they know their place. My cats talk, they just don’t make much sense.