Perhaps the unlikeliest of last year's notable comics was The Bulletproof Coffin, a superhero-damaged, pop art-inflected monthly that carried, in equal measure, deep, yearning nostalgia for the Silver Age of the 1960s and cynical scorn for the current state of mainstream comics. Bulletproof was neither the work of remarkable new talents or all-time greats, but two footnote-level creators, artist Shaky Kane and writer David Hine, who seemingly couldn't hold back what they had to give for a second longer. Over the second half of 2010 an almost unknown, psychedelic Jack Kirby acolyte and a solid-if-overlooked writer of B-grade Marvel and DC books were suddenly saying the most relevant things about superheroes and the comics industry that had been heard in quite some time.

Perhaps the unlikeliest of last year's notable comics was The Bulletproof Coffin, a superhero-damaged, pop art-inflected monthly that carried, in equal measure, deep, yearning nostalgia for the Silver Age of the 1960s and cynical scorn for the current state of mainstream comics. Bulletproof was neither the work of remarkable new talents or all-time greats, but two footnote-level creators, artist Shaky Kane and writer David Hine, who seemingly couldn't hold back what they had to give for a second longer. Over the second half of 2010 an almost unknown, psychedelic Jack Kirby acolyte and a solid-if-overlooked writer of B-grade Marvel and DC books were suddenly saying the most relevant things about superheroes and the comics industry that had been heard in quite some time.

Bulletproof Coffin is at once a candy-coated, psychedelic romp through uncomplicated vintage-superhero tropes, and a savage condemnation of a static and overly commercialized comics business that's lost its motivating sense of wonder. The accusations spew in all directions: hero comics' current malaise, according to Kane and Hine, is equally the fault of corporate lawyers, big-media buyouts, apathetic creators, and a fan base that refuses to grow up and look real life in the eye. It's an unusual, compelling book, one that opens up a truly uncomfortable line of questioning about who the reader is and what they're doing reading a comic when they could be out having a beer and getting laid—and in the same breath offers eye-burning clashes between jungle girls and undead Vietnam vets. With the recent release of the Bulletproof Coffin collection, now seemed as good a time as any to ask Kane and Hine just how they rendered something so unique from decades-old spare parts.

TCJ: So how long have you two known each other? How did you meet, why did you decide to start working together?

HINE: I first met Shaky more than three decades ago. Good God, doesn’t the time just fly by! We were both living in Exeter in England’s West Country, and we were both punks at the time. We listened to the same music, dyed our hair and customized our clothes with fetching little designs. My first punk clothing was a jacket with added bullet holes and blood. The punk community was fairly small so it was inevitable that we would bump into one another and we found we shared all kinds of other interests in comics, literature, and art.

KANE: I first met David in a subterranean drinking hole, situated beneath the Mint public house in Exeter. It was one of the few licensed premises that actually played punk records or for that matter served "people like us." The people in point being a small band of local art college students and disaffected youth who followed the fringes of fashion and music of the time. This would have been 1976 or possibly '77, it was that long ago. As part of a college course David was putting a comic book together, entitled Joe Public. I volunteered a strip, and so spent the next couple of weeks drawing up a sub-poetic angsty offering entitled "Hitler On Ice". Apart from a punk collage in a local fanzine, the short lived Stranded, this was my first published work.

HINE: For a while we were living in the same house. I was at the art college and I commandeered the college printing press to publish Joe Public Comics. I asked Shaky to do something for it and he came up with "Hitler on Ice", which still stands the test of time as a chilling illustrated prose poem. It was so good I opened the comic with it. Apart from that and me inking a few of Shaky’s drawings, we never thought to collaborate because we both believed that most of the best comics are produced by writer/artists, so neither of us was looking for a collaborator.

We went our separate ways after Exeter, though we did seem to end up working for a lot of the same publications. We both had illustrations in the New Musical Express, both worked for Deadline and 2000AD. There was a long period when we didn’t see one another. About ten years I would think.

KANE: You know the way these things go -- we just drifted out of each other’s lives. Our careers, as such, ran parallel courses. David hung on in London. After 15 years, including a short lived and humbling stint as an "artdroid" at Fleetway, I decided to call it a day. My meteoric career had burnt-up on re-entry. I sold my flat in North London and moved back to the South West. I still kept up my drawing along with my interest in comics. Whenever the opportunity arose I’d stretch my creative muscle. I’d even turn up at conventions, but now as a member of the public. To be honest I rarely met anyone who read comics once I’d left the scene, certainly nobody who had heard of Shaky Kane. But I kept drawing, simply because that’s what I always did. I’d evolve ideas along the way, characters and even settings in which to place them. It was certainly running into David at Bristol that got me figuring again. David was now a "name" writer. I’d bought Daredevil Redemption. To realize that childhood dream the way David had, it seemed almost magical to me. But David was still the same guy I had known all those years ago.

HINE: Then I bumped into Shaky again at a comic convention in Bristol. I think that was 2008. I was coming down from my hotel room in the lift. The doors opened and there was Shaky with his wife and son. Fate threw us together. We spent hours in the bar talking and we found we still had the same jaded twisted view of life in general and comics in particular. I had moved on by this time though. I had more or less given up on the drawing and was writing full-time for mainstream comics. That has been fantastic but there’s a lot of frustration working on properties that belong to Marvel and DC, not to mention the inevitable editorial oversight, restriction, censorship. I’ve been feeling shackled by the medium instead of set free by it. Comics is a medium where you can do literally anything you want and yet I was feeling like my creativity was being stifled. I was a writer in search of an idea and an artist who is totally on my wavelength, and by the time we’d been talking for a while it was obvious that Shaky was the man. I say it was obvious but I think it was a while later that it occurred to me that we should actually do something about it.

TCJ: Who came up with the Bulletproof Coffin idea? What kind of process did you go through to develop the idea into a comic?

TCJ: Who came up with the Bulletproof Coffin idea? What kind of process did you go through to develop the idea into a comic?

HINE: The idea was Shaky’s. He had the name and a sketch of the Coffin along with notes and sketches of the characters. Coffin Fly, Red Wraith, the Shield of Justice. He also had one page drawn where Coffin Fly is driving the Bulletproof Coffin across the dead planet and stops to find an arm sticking up out of the ground wearing a wristwatch. That eventually became page 4 of issue 3. Shaky’s notes were full of phrases like “Shield of Justice walks the dead beat.” And the idea of a Legion of Dead Super Heroes was there.

KANE: I think I spent the following year putting all the random ideas together. All the characters were already decided on. Even the "Bulletproof Coffin" itself was in place. I imagined it quite literally as a mobile bulletproof coffin, a vehicle to house the soul of a dead hero. I had the idea of a comic book Valhalla, a place where dead heroes still battled on! Real Kirby Konsciousness! But what it needed most of all was a writer. Someone who could make a logic out of all this stuff. I hated the idea of asking David. David’s career was really taking off and I was Green Kryptonite in my mind! I didn’t imagine that anyone, any publisher in the world would be interest in what I had to offer. David took those ideas and made it cohesive. I don’t know how he did it, but the script he came back with took the whole thing to another level. I had something I actually felt good about drawing.

HINE: Once we decided to do something, I looked at those notes and came up with a plot where this guy called Steve Newman finds a treasure trove of old comics that shouldn’t exist. He’s a Voids Contractor. This is a real job. Voids Contractors are the guys who empty houses when someone dies with no relatives. I read in our local news that these Voids Contractors had gone to the wrong address and busted into a house, cleaned it out, dumped this old guy’s possessions. His entire life went into landfill. It was his next-door-neighbor who had died. What a tragic story! So that’s where Steve Newman came from.

HINE: Once we decided to do something, I looked at those notes and came up with a plot where this guy called Steve Newman finds a treasure trove of old comics that shouldn’t exist. He’s a Voids Contractor. This is a real job. Voids Contractors are the guys who empty houses when someone dies with no relatives. I read in our local news that these Voids Contractors had gone to the wrong address and busted into a house, cleaned it out, dumped this old guy’s possessions. His entire life went into landfill. It was his next-door-neighbor who had died. What a tragic story! So that’s where Steve Newman came from.

I liked the idea of putting us into the story as the Creators. We’ve been no more than a footnote in the history of comics, so it was cool to create an alternative world where we were as famous and influential as Simon and Kirby or Lee and Kirby. There’s a lot of Stan’s schmaltz in the writing but also a lot of Joe Simon’s kookiness. And of course there are elements of the writers and artists that we were into back in the '70s -- William Burroughs, Andy Warhol, Adam Ant. A lot of love for bad movies too, and all that junk culture like bubblegum cards and the crazy shit that was advertised in the back of comic books.

TCJ: What was your collaboration on the book like? Both of you have drawn and written comics, was there a neat division of labor between writing and visuals on Bulletproof or did you both contribute to both things?

KANE: Coming from the same cultural background, David knew exactly the angle I was looking for. It was a mutual agreement of intent! He put all of those details into it. Steve Newman, his job, his family. He made it work as a story. Getting the script in was really something. I wanted this book to work, so I probably put in more hours on the art than you'd ever imagine. This was my chance to show people that I wasn't the gimmick, the crappy Kirby. Over the years away from comics my drawing had evolved and for the first time I was happy about the way it was looking.

Left to my own devices? Well, I can't imagine I would have been able to fill a book.

HINE: I did most of the writing and Shaky did the art. But we have endless discussions. I had some very specific ideas about the way some of the pages should look, and Shaky gave me a lot of input into the writing – more in the first issue where he inserted a few lines, like the quote from Destroyovski at the beginning.

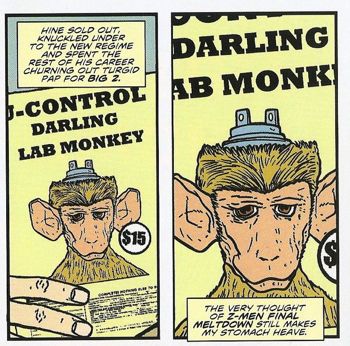

I did do the awful Photoshopped color on one page in the last issue, where we have that Image style superhero comic cover for The Legion of Dead Heroes by the spoof artist Spandax Groyne. Shaky drew. I colored. Shaky came up with the Spandax half of the name, I contributed the Groyne. But to be honest, I no longer remember who came up with a lot of the stuff. The Hateful Dead bubblegum cards were Shaky’s. He already had the drawing for those. There’s an issue where we had a letters page. I wrote half of them and Shaky wrote the rest, but I defy you to identify who wrote which of those.

KANE: Being an artist, David thinks visually. He worked to my strengths. We had a few, not disagreements, but maybe we felt some element should have been slightly different. But at the end of the day I had full trust in David. He was the one with the track record. He knew how these things worked. I can't imagine anyone else coming up with this stuff. David brought an intelligence to the project. I wouldn't consider myself an intellectual by any stretch of the imagination!

KANE: Being an artist, David thinks visually. He worked to my strengths. We had a few, not disagreements, but maybe we felt some element should have been slightly different. But at the end of the day I had full trust in David. He was the one with the track record. He knew how these things worked. I can't imagine anyone else coming up with this stuff. David brought an intelligence to the project. I wouldn't consider myself an intellectual by any stretch of the imagination!

HINE: That’s what I enjoy the most about doing The Coffin – we sit around drinking beer or talking for hours on the phone about this stuff and we’re just bouncing ideas off one another constantly. We sometimes argue about minor points, but really, really minor stuff. I guess in the end I’m more disciplined when it comes to the plotting. Shaky goes off on insane tangents that are really wild and it’s my job to find some way to turn those ideas into some kind of near-linear storyline. Not too linear though. We don’t want to wind everything up too neatly.

When I first read Burroughs’ Naked Lunch it haunted me precisely because I didn’t understand half of what I was reading. It’s the same with David Lynch’s movies. You come out of his movies with your head spinning, trying to figure everything out and just when you think you have a grasp on it, it slips away like a greased pig. The best works of art always leave things unresolved. The only real criticism of The Bulletproof Coffin that I have seen is that maybe we tied things up a little too neatly in the end. But in fact if you take a close look you’ll see that there are more questions than answers. Not to mention enormous plot holes and dangling threads. All deliberate, of course.

TCJ: Bulletproof Coffin is pretty unashamed about being a superhero comic, but it's obviously not the typical thing done in that genre. Can you talk about some influences that you might have pulled from outside mainstream superhero comics? For example, Shaky, last time I interviewed you, you talked about Brett Ewins -- how does his influence figure in you guys' work? Any influences from American alternative comics?

KANE: I can’t say that Brett Ewins was an influence on drawing The Bulletproof Coffin. Although maybe the feel of his early stuff. The stuff he did with Brendan [McCarthy], do you know Sometime Stories? I can see a hint of that in my work. It filtered down into my subconscious. But I just draw the stuff. There isn’t any big overview.

HINE: I think it’s clear that the major influences are silver-age Marvel and to an extent, DC comics. I was knocked out by my first experiences of American comics, which were the Lee/Ditko Spider-Man and the Lee/Kirby Fantastic Four, then Thor, Hulk, Dr. Strange. At the same time I was picking up a lot of Alan Class Comics. These were cheap -- and cheaply produced -- black-and-white reprints of American mystery and horror comics from the 1950s. They were fairly random collections from across a range of publishers, but there were masses of Ditko shorts and I loved them. The storytelling was so perfect. He used the 9-panel grid decades before Watchmen and I’ve always gone back to them for key scenes where you have to get across a lot of visual detail in a limited space. You get a snapshot effect where you can focus on detail in close-up -- a droplet of sweat, a clenched fist, a weird African idol, a cockroach crawling across the floor – details that would go unnoticed without those close-ups. It’s a kind of visual grammar that’s unique to comics.

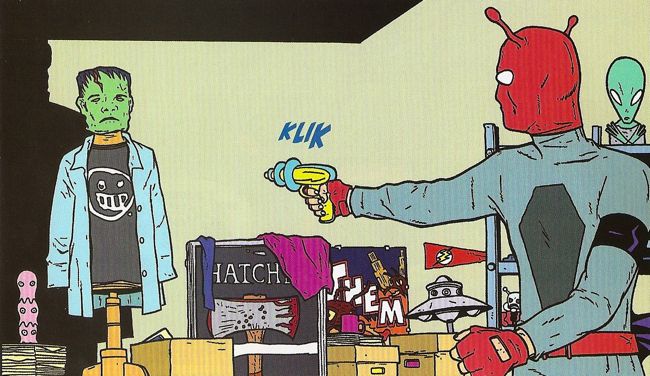

KANE: Some of the detailing has its own back-story. Page 2, issue 2 for instance [below]. In the first panel the Coffin Fly tries out his ray-gun. The tailor’s dummy he’s using as a target is wearing Steve’s Frankenstein mask along with a Newbury Comics "Tooth-Face" T-shirt. Next to that arrangement there’s a framed poster for the low-budget horror movie Hatchet. The lead in Hatchet wore a Newbury Comics shirt throughout the movie. Newbury Comics actually picked up on that detail. I told them how when I was in Boston I visited the store to buy a Newbury Comics/Hatchet souvenir shirt, only they were sold out. They actually sent me one through the mail. That's almost product placement!

I always put in Adamski references. As anyone who’s seen Shaky Kane Unraveled would know, flying saucers are one subject that Shaky Kane takes very seriously!

HINE: Alternative comics influences are harder to pin down, but I find I’m fascinated by a lot of the same subject matter as Charles Burns. Richard Corben is another master of storytelling who influenced me a lot. I’m fanatical about Robert Crumb but I’m damned if I can figure out if he’s actually influenced my work. Probably on a psychological level somewhere. I’ve also been very much influenced by European creators. Hugo Pratt, Comes, José Munoz, Tardi, Jean Giraud, Loustal. There’s a very long list and their collective body of work is stunning. That influence is most obvious in my drawing on Strange Embrace, but it will probably be more to the fore in the second series of The Bulletproof Coffin.

KANE: I don’t really know anything about American alternative comics.

Although, saying that, Frank Santoro sent me whole package of books when I drew the cover of Comics Comics. It was quite an eclectic bunch. Great books to own, but I always see myself as pretty straight when it comes to actually sitting down and drawing.

TCJ: Last year Bulletproof Coffin became part of a unique aesthetic moment for comics, along with two other Image books, Brandon Graham's King City and James Stokoe's Orc Stain -- something Frank Santoro himself named "fusion comics." Did either of you read those comics? What'd you think?

HINE: Does that make us Fusionistas? Hot damn! I always wanted to be part of a cool art movement. I know what Frank means. My own influences cut across so many genres and styles, including manga and British comics. I also go to galleries, watch tons of movies, read quite widely, and waste huge amounts of time surfing for trash on the internet. So yeah, we’re soaking up a very wide cross-section of media and that makes for an eclectic style of genre mash-up. I don’t really think in terms of "high" and "low" art. Whatever I’m doing I try to apply the highest level of discipline to create the best work possible and I also try very hard to be entertaining. I get bored to death by badly conceived, poorly executed comics that lay claim to some kind of artistic credibility through willful obscurity. (I don’t mind willful obscurity if it’s shit-hot though.) I think it would be horrible to set out to produce fusion comics as some sort of intellectual exercise, but I guess a lot of us are so familiar with all this stuff it becomes part of our language. That combination of word and image is utterly instinctive and unselfconscious because we’ve grown up with it and spent our lives absorbing it all. Basically our heads are totally and permanently fucked up.

KANE: Fusion comics? It's always something to be part of a movement. But I’ll have to own up. I never actually read either of those titles. Give me a call when the Fat Paycheck Movement gets rolling. That’s the one I’ve been waiting for!

HINE: I admit to not following enough of my fellow Image creators. I have only picked up one issue of Orc Stain. There are two kinds of people in this world and I’m one of the ones who slink away into the shadows at the merest whisper of the word "orc." The "stain" part of the title negated some of the negativity. That and the beautiful artwork persuaded me to pick up a copy a few weeks back and it impressed me enough to keep mentioning it to people. However I do need to immerse myself in it some more before I make any real comment on it beyond recognizing that it’s totally unique and the work of a strangely twisted mind. I keep hearing good things about King City, so excuse me while I go download a copy. Back in twenty minutes or so…

Okay. I checked this out on Tokyopop’s site. It’s a little too softcore for me. Very slow pacing. It’s almost like a science-fiction Joe Matt comic without the wanking. The drawing is good, the jokes are low-key and subtle –- probably too subtle for me. I feel like I want to turn the volume up on it. It’s not a criticism, just a case of different strokes. Bone wasn’t my kind of book either, though I recognize that it was the work of a consummate craftsman. To give you some idea of what I really do like, my all-time favorite original English-language manga from Tokyopop was MBQ by Felipé Smith. That was psychotic, hilarious, and utterly brilliant.

TCJ: What was it like to create a comic for Image, how did it work out creatively, editorially, financially? How did it compare to making work for your old publishers in the UK? David, how different was it from doing work-for-hire at Marvel and DC?

HINE: Creating for Image is actually creating for yourself. There is absolutely no restriction whatever on what we do beyond a few irritating details like price, page count. It would be insane to bring out a book that was twenty pages one issue and fifty the next, though if we really wanted to do that I’m sure we could work something out. When I pitched this book to Eric Stephenson he took two seconds to make a decision. He was so into Shaky’s work that he would have greenlit a Shaky Kane-illustrated telephone book. I can’t tell you the joy I get from not having an editor looking over my shoulder.

KANE: As far as I was aware I might as well have been working for [Richard Starkings' publishing house] Active Images. We had a lot of contact with Richard Starkings, J. G. Roshell, and Jimmy Betancourt. They were my experience of working for Image. I even ended up shooting them, on the page that is. Imagine doing that to Todd McFarlane! I can’t imagine that going down too well. Or Stan Lee for that matter. Although didn’t he drink that contaminated soda in the second Hulk movie? Maybe he would be up for getting shot.

HINE: I don’t want to be too down on editors because I have worked with some terrific editors. In the mainstream they’re obviously indispensable to coordinating and managing the production of books, and in the case of Marvel and DC, of making sure you’re working within the parameters of what a set of characters should be doing. You’re part of a team and you have to be aware that the characters don’t belong to you. There are a lot of negative aspects to that, but it’s not all bad. My writing has improved a lot through the discipline of working within limitations. I also get to write Inhumans stories, Batman, Green Lantern, and recently the Spirit. With Fabrice Sapolsky I created a communist Spider-Man for Marvel’s Noir line and that was really very cool. It presses all my geek/nerd buttons to work on those books and even though I have huge reservations about the whole vigilante thing where a violent confrontation is always the ultimate resolution to conflict, I do get to work with some of the best artists around and to reach a relatively large audience.

Contrary to what some people have suggested, I don’t see my work for the Big Two as hack work in the sense of hacking it out without due care and attention. Quite the opposite. I work twice as hard to make these mainstream books as good as I can make them. The last thing I want to do is alienate readers. Nothing makes me feel worse than reading a review from a disappointed reader. Every comic should be a pleasure to read and I do everything possible to get to the heart of the characters, keep their integrity and respect the continuity of existing stories. But I also want to insert something of my own into those stories, maybe even subvert the form a little. I’m not a great believer in the superhero as an archetype, so I will always chip away at their image as far as I can. And I’ll avoid the big final smackdown whenever possible, though there are times when I have been literally ordered to write fight scenes.

One thing I find hard to take is having scripts re-written at editorial level without consultation. That rarely happens now, but there was one occasion where I barely recognized the printed version of a book I wrote. That one time I actually sat down and compared the printed version to my script and found sixty-nine separate revisions. And I don’t mean sixty-nine words. Some of those revisions were entire captions or balloons.

There have been times where I’ve felt a real lack of professional courtesy towards myself as a freelancer and talking to other writers and artists, I’ve heard a lot of very similar stories, so it seems to be commonplace. There’s always a conflict between art and commerce and I guess I’m lucky to be able to both make a living through mainstream comics and find an outlet for the more creative work through Image.

It’s just a real pity that the sales numbers don’t correlate to quality. I know that The Bulletproof Coffin is the best comic I ever worked on. For various reasons, Civil War: X-Men was one of the weakest. Yet the X-Men series sold over twenty-five times as many copies, not to mention foreign sales and reprints. The financial rewards are not there yet for The Bulletproof Coffin. Ultimately it may pay better than mainstream work. It depends what sales of the trade paperback are like, if there are foreign editions, whether legal digital downloading takes off. Independent comics are financially precarious. A few thousand extra sales can take you from break-even to making a living and if you have a breakaway hit like The Walking Dead or Chew, you are going to be making really big bucks.

TCJ: Let's talk about the superhero. What did you guys want to do with that specific archetype in Bulletproof Coffin? Do you feel like you fulfilled the goals you had for superheroes?

TCJ: Let's talk about the superhero. What did you guys want to do with that specific archetype in Bulletproof Coffin? Do you feel like you fulfilled the goals you had for superheroes?

HINE: The superhero… yeah. Hate superheroes. Love superheroes. The thing is that when I was a teenager, the best comics I could find (this is in the mid to late sixties and before I saw underground and European comics) were Marvel and DC comics and a few Charlton books. I didn’t particularly go for superheroes. If EC books were around in those days, that’s what I would have been reading. I loved Ditko and Kirby. That’s whey I read FF and Spider-Man. I never much liked the big team books like X-Men, Avengers, Justice League. Having said that, when Neal Adams drew the X-Men it was the greatest comic in the world. But given the choice I would go for anything but superheroes. Steranko’s S.H.I.E.L.D., Ditko’s Dr. Strange, Wrightson on Swamp Thing, Barry Smith’s Conan, Kubert on Enemy Ace or Firehair, Kirby on Sgt. Fury. I was crazy about the DC mystery books – anything by Alex Toth. I did enjoy the really nutty "superheroes" like Hawk and Dove, the Creeper. Anything by Ditko, even if I did feel weird about the way he depicted hippies. I always had the sneaking suspicion that I’m everything Steve Ditko hates. But I still love him.

Outsider superheroes like Spider-Man and the Silver Surfer were fantastic. Squads of vigilantes standing for the American Way—not so much. If you look at the superheroes of The Bulletproof Coffin, they aren’t really traditional superheroes at all. Red Wraith is a spooky mystery guy like a cross between Deadman and, I don’t know, Doctor Strange, I guess. The Unforgiving Eye is Ditko’s Mysterious Stranger crossed with the Phantom Stranger, crossed with Dr. Strange. Strangeness abounds! Ramona is Sheena and Rima and all those other scantily-clad jungle heroines whose name ends in a sigh. The Shield of Justice is a dead cop with a truncheon. Coffin Fly is a guy with a home-made costume and a ray gun. Christ knows where he came from.

KANE: I’d worked in comics in Britain for a number of years. I even had an ambition at one time to actually earn a living doing it. I never thought about it as a career plan as such. Just to be in a position where I could spend my working hours doing the thing that I really loved. I had this love affair going with a specific period in the evolution of American comic books, one that I had kept true to in my approach to drawing. It was probably not the most realistic of dreams to follow!

Somehow, during the late eighties, early nineties, I don’t quite know how, I found work with most of the big publishers of the time. I was always met with a mixed reaction from British comic readers. They were mostly sort of dark fantasy/sci-fi fans. I don’t think they shared my personal vision! I was given a lot of work, for a number of years, but it never quite gelled. The scripts were on the most part not quite what I was hoping for. I was given the humor stuff. I was the cartoony guy. I think Bulletproof came at the right time. It was nice for once, apart from the times when I put out my own projects, to actually draw something that I felt good about putting my name to.

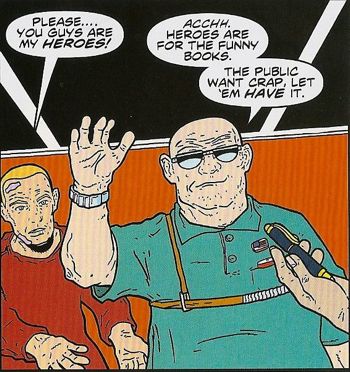

HINE: It’s not that easy to articulate what I feel about superheroes but I think you’ll get what both Shaky and myself feel about them from reading The Coffin. We’re conflicted. But we definitely hated the way they went in the late '80s and '90s. All those slick digitally painted multiple-covered gold-plated turds. They turned me right off American mainstream comics for at least fifteen years and there’s still too much of that false sophistication, which doesn’t alter the fact that most of that stuff is still just adolescent boys' fantasies masquerading as "serious" art.

KANE: I feel like I fulfilled my goals. Bulletproof has the stylized veneer, the one I became enchanted with, all those years ago. But it's also got a lot more going for it, thanks to David’s personal obsessions and the cynicism that comes with age.

TCJ: Bulletproof exists in kind of a strange space for superhero comics, where there's a very obvious element of Silver Age nostalgia and "fun-comics" zaniness -- but also a very dark, grim bent that's only really come to superheroes since the mid-'80s or so. Both in writing and art, the '60s pop seems pretty shot through with a Frank Miller-ish cynical darkness. Was that combination a conscious choice, or just a product of trying to make the kind of comics you liked?

KANE: I think that’s exactly what worked about Bulletproof.

I’ve always strived to present work that has a duality to it. Even the early work for magazines like Deadline, or even say a throw-away strip like "Johnny Tomorrow" from Escape. Obviously with a visual media like comic book it’s the art, the surface which primarily impacts. At a casual glance my art might even look naïve -- this isn‘t the way comics are supposed to look nowadays. It's only when you start to read the thing and take in what’s happening in this visually unsophisticated comic book world that the inherent madness in David’s script starts to seep in.

HINE: I could never be as cynical as Frank Miller, but I always liked a dark side to my comics. I never read comics in isolation. I was always reading a lot of novels and watching a lot of movies. Film noir, art movies by guys like Tarkovsky and Polanski and Lynch. I listened to the Cramps and Patti Smith and the Pistols and New York Dolls, and I read Burroughs and Kathy Acker and Ray Bradbury and Ballard. All of that goes into the mix.

That goes for Shaky too. He just comes out with cool stuff. He doesn’t have a plan. I do have a plan. But I start off letting everything come out in a stream of consciousness. I let the plot take whatever direction it flows off in. Then when I have masses of material I start to tweak and manipulate it. It’s tricky because I never want to be so disciplined that the fun goes out of it. Entertain first, but layer the scripts with other meanings. Anxiety and alienation are the themes that always come through in my stories. And that’s about all I want to say. I don’t want to analyze The Coffin too much. People are getting it. I’ve read a lot of very in-depth reviews, by yourself among others, and you’re all getting it. Totally. So our job is done.

KANE: Drawing the books, even I found it hard to keep up with the logic of the shifts from Steve Newman’s world, which was uncompromisingly comic book in nature, and the inner world that Steve discovered in the comic books he came across at the old guy’s house! Its along the lines of asking yourself what TV shows do TV characters watch on TV! I had a pretty good idea that David was going to guide this book down a fairly uncharted course.

Comic book art. It always sounds like a put-down. It looks cartoony. I’ve always wanted things to look cartoony. There’s a whole world of art out there. If you don’t like cartoons, don’t read comic books. Go look around some galleries, hey! But that’s too artsy for most comic book readers.

TCJ: Especially toward the end, there's a lot of pretty heavy overtones in Bulletproof that point toward the decay of the superhero -- the decadence, both in marketing and concept, that the genre's entered into. In the final issue hyper-action slows down into '90s-Image posing, corporate greed, bitter old guys, and then finally nothing at all. Is all the BIFF and POW really meaningless in the end? Is the superhero dead?

TCJ: Especially toward the end, there's a lot of pretty heavy overtones in Bulletproof that point toward the decay of the superhero -- the decadence, both in marketing and concept, that the genre's entered into. In the final issue hyper-action slows down into '90s-Image posing, corporate greed, bitter old guys, and then finally nothing at all. Is all the BIFF and POW really meaningless in the end? Is the superhero dead?

HINE: You know what? The real statement we’ve made is to create a comic that can’t be adapted as a movie or TV series or a novel or stage play or anything else. It’s the purest comic you can imagine. I fucking hate comics that are movie pitches. It’s nothing to do with the death of the superhero. It’s the death of the cheap throwaway comics that you roll up and stick in your back pocket or pile up under your bed and come back to and re-read over and over because you love them in a way that you cannot love any other medium.

I’m not blaming anyone for selling out. If some Hollywood producer comes to us and offers us big bucks we’ll sell out as fast as anyone – that’s what the final chapter is about. We’re not saints. Our ethical standards are probably not much higher than anyone else’s but at least we have the good grace to feel bad about it. And we have made a comic that is as good as we can do with whatever skills we have. I just wish we could have printed it on cheap newsprint and sold it for ten cents a copy.

KANE: When I was at school I read comic books. Imported American comic books. I certainly wasn’t thought of as a trendy "geek." To the other school kids it marked me as immature and, quite honestly, an unsophisticated person. And this was during the time when Jim Steranko was on board, Jack was at his height of his artistic strength. But it was lost on the vast majority of people. I don’t know what it was like in America, but all that wonder that David and myself found ourselves so besotted by had no cultural impact whatsoever. It was dismissed as wretched gaudy junk.

Now forty years later, I’m taking my boy to school and the kids have got Super Hero Li'l Kiddle back packs and even their dads know who Wolverine is. But they don’t really know where those characters came from. They don’t know who actually sat down and thought those characters up. Why would they? It's just marketing. They’re not comic fans. They don’t read comics. But if you were an executive at a comic book company you’d be easily fooled into imagining they did. So you put out thousands of titles, every possible permutation of the same theme. You know… might just come up with the next Spider-Man. And sometimes they luck out. Look at Kick-Ass, great book and box office hit, now that must have got them figuring.

Let's bring out yet another Wolverine comic, only this time lets have him dripping in blood, have him really fucked up, big up the cussing. Cutting edge, man, cutting edge. But it doesn’t work like that. You can’t sell comics, not in the quantities it takes to keep all those guys in a job, to a public that doesn’t even want to know about comics. Even the most delirious devotee would be hard pressed to keep up with all the multiple covers and crossovers on offer. And to top it off they all look so ugly.

The comic book shelves, to a casual browser are mind blowing to contemplate. It’s a sea of Skrull-chinned zombie carcasses, painted by, and I could be wrong here, the same guy who knocks out landscape paintings for the tourist market in a some far-off subterranean sweat shop.

What was the question again?

TCJ: Don't worry, you answered it.

So both of you seem to have a pretty dim view of comics' increasing crossovers with Big Media. I can see where you're coming from, 100 percent... but isn't it unavoidable that comics and that lowest-common-denominator aspect of pop culture intersect? Without putting too fine a point on it, both of you are familiar with the grinding reality of actually trying to get paid for producing purer comics with no "media potential" to them. Is there a way for "comic book comics" to survive?

KANE: Well, I’ve had such a positive critical response to my work since Bulletproof, that in its own way has been a reward. I’m back on the UK convention tables, this time not just as "that guy who used to draw The A-Men." Last one we went to we actually sold every single item on the table.

Of course "comic book comics" can survive as long as you don’t expect the big publishers to see the commercial value, the marketability, of your work. But a lot of people have looked at what David and myself have produced and picked up on it. As for anything being unavoidable, as any comic book reader could tell you, there are infinite parallel paths that comics' evolution has taken, only we’ve somehow got tricked into taking the noncommercial path. There’s probably an Earth-2 Shaky Kane sitting back in the La-Z-Boy, right this very moment, feeling pretty smug about being the King of Comics!

HINE: I don’t mind TV and movies adapting comics. When they’re good, I enjoy them as much as anyone. Loved seeing Spider-Man and X-Men on the big screen. Kick-Ass was exactly what it said on the box and I enjoyed every minute of it. I’m looking forward to seeing the Walking Dead TV series. Some comic-based movies have been absolutely dire. None of that really matters. It’s the fact that selling an idea for a comic book has become so tied to its commercial possibilities in other media. There is a pitching process now, which feels as cynical as the process for pitching movies. And there’s a sense of desperation among creators to get their books optioned by some Hollywood or TV producer. Even comic book fans give greater respect to creators who have that link to Big Media. It’s epitomized by San Diego where the so-called Comic-Con is a feeding frenzy for other media, while the comics themselves are almost ghettoized.

I have a great love for the print medium but the future is inevitably going to be linked with digital comics and that’s not such a bad thing. I’m not a complete Luddite. Now that we have the iPad and other similar hardware to deliver digital comics it is looking like a genuine alternative. I love seeing Shaky’s art on my iPad. It’s even more eye-blistering. The point is that it’s just a delivery system and it doesn’t seriously distort or corrupt the form. It’s still comics.

For the moment there isn’t a huge income from digital sales but I’m confident that it will expand our audience, particularly among young people. If anything is going to save the art form, digital comics is it.

TCJ: After your experience with Bulletproof -- a huge critical hit, a significant aesthetic success, and a more modest commercial one -- how do you two feel about comics right now as an artistic medium? And are those feelings different from your feelings about comics as a commercial medium?

KANE: It hasn’t changed a thing. The end result, the printed comic book, the one I pull out of the Fed-Ex box, the one I hand to my nine year old son. That is as far as I can be expected to take the project. Beyond that it’s in the realms of speculation. Will people like it? How many will it sell? Its down to pre-orders. Orders put in two months before anyone’s actually even seen the book. To my way of thinking, that document is a piece of art. I can honestly see no difference between that object and a giclée print hanging in a gallery. Or for that matter the objects dreamt up by the celebrated artists of our age. I didn’t physically print the thing, but then I’m fairly certain that Damien Hirst didn’t paste the diamonds onto the skull. Once money changes hands, all distinctions between the commercial and art worlds become meaningless.

HINE: It has been very frustrating to get this overwhelmingly positive response to The Bulletproof Coffin and still get relatively low sales. We know there is a big audience out there if we could only reach it. I’ve heard from a lot of store managers that they sold out very quickly of the first issue and couldn’t get more copies. Our sales stayed solid at more or less the same figure for the rest of the series. The problem with a limited series is that you can’t grow sales. Few people who missed the first issue will buy the second. They’ll wait for trade. Comics are unusual in being so much at the mercy of the people who run the shops. There have been a number of shops in the UK and elsewhere that have been very supportive. That means steering the fans towards The Bulletproof Coffin. Where that happens our sales have been really high. When I was in New York last year, a guy bought ten sets at cover price for his store. He was willing to forgo a profit to supply his customers when they ran out of copies. That’s amazing. It does make me feel very positive about a second series.

As an artistic medium I’m very positive about comics. In the history of comics there have never been so many great comics being produced. There’s a greater variety of comics and a very high quality of work. Most of them make no money and that tells me that the creators are in many cases doing this out of love for the medium. Okay, there are some who self-publish with the hope of breaking into the big time, selling the movie/computer game/TV rights to their property and so on. But there are also many many people who do this simply because they can. It’s never been easier to self-publish. It’s possible to print very low runs with modern print techniques and there are a huge number of conventions and comic expos where small-press creators can sell their books. The comic book is a medium where one or two people can produce the entire product from start to finish.

What I find disappointing is that so much of the British small-press product is trite or superficial. There don’t seem to be many dangerous comics out there. Everything is very tame compared to the underground comics of the '60s and '70s. I do pick up small press comics when I can and some of them look good, but there really isn’t anything that that I can really enthuse about. Maybe it’s me getting hard to please in my old age, but I don’t think that’s it. I still see amazing work that does really get me excited, but it mostly comes from the USA or Europe, with the honorable exception of SelfMadeHero, who are publishing some excellent books. Markosia have some good books too, though they can be hit and miss.

Honestly though, it’s hard to keep your integrity when it’s so easy to compromise to make a living. All the self-flagellation in The Bulletproof Coffin is a reflection of that.

TCJ: Finally, I just have to ask -- David, you mentioned a second Bulletproof Coffin series? Let's hear at least a little something about that!

TCJ: Finally, I just have to ask -- David, you mentioned a second Bulletproof Coffin series? Let's hear at least a little something about that!

HINE: My collaboration with Shaky has been so successful, that I really did want to carry on beyond the first series. I have nightmares of Shaky being tempted away to work with other writers. It’s hard to find an artist that I really feel comfortable with and Shaky can only produce one series in year, so I wanted to jump straight into another series. It will actually be a year between the end of the first series and the launch of the second. We want to be sure that Shaky has enough art completed that we can publish six monthly issues on time. We’re planning series two to launch in December of 2011, tentatively titled The Bulletproof Coffin: Disinterred. There will be links with the first series. Some of the characters will return and we’ll be picking up on some of the plot threads. But you won’t be seeing Kane and Hine this time round. The structure of the series will be very different. Six self-contained but linked issues.

KANE: The first series was so perfectly self-contained that any attempt to duplicate it... well, we'd be on a hiding to nothing. But in the process of drawing these things, and I'm talking many hours here, the details of the story play through your mind. What we're planing to do this time around is use the ideas within the first series as springboards for further imaginings.

For instance we might ask, who was the Shield of Justice before he died? There's a whole story there, not necessarily rooted in the Golden Nugget books. What were the circumstances surrounding the Hateful Dead? The bubblegum cards we included in issue 3 imply a conflict beyond the events described in the books. What about the scene of the murders in issue 4, "Done because we are too menny (sic)"? There's a whole book in there! Could anyone be The Coffin Fly? Steve stumbled across the costume, but was he the first?

We might well come up with some answers, or just play with the ideas. These thing evolve the more you look into them... David knows what he's doing! We're going to mix it up, keep the readers guessing. Build on the first series.

HINE: We don’t want to repeat ourselves. It’s important to us that The Coffin is always fresh, always unpredictable. We’ll be taking more chances with some of the stories. We could have played safe by simply producing titles from that endless cache of "unseen" Golden Nugget Publications and I’m sure that would have been fairly popular, but we prefer to take a few chances and explore some new creative directions. If you ever read an issue of The Coffin that is exactly what you expected, then we’ve screwed up.