To mark the release of Chris Ware’s decade-in-the-making Building Stories—a box of fourteen print artifacts ranging from cloth-bound volumes and newspapers to broadsheets and silent flip books—The Comics Journal is featuring a series of essays from the contributors to the 2010 volume The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking (University Press of Mississippi). Each contributor is revisiting the argument they made in that edited collection two years ago in light of the newly released work, speaking to the ways in which Ware’s comics have either transformed in that time or are returning to the themes of his earlier publications. We hope these first thoughts give rise to a spirited discussion about a novel that will shape conversation in the medium in the years to come.

Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth is, in part, a comic about the history of Irish immigration to Chicago and the Irish immigrant’s inevitable assimilation into white Americanness. Indeed, even though his grandfather had been mocked as a “little micky leprechaun” at the turn of the twentieth-century, Jimmy is utterly deracinated by its end. But Jimmy Corrigan is also about men making generations they do not intend to acknowledge. Through careful exploration of the Irish and African Corrigan family tree, Chris Ware teases out the buried interracial family legacies lost to us as a result of hundreds of years of slavery and sustained apartheid. As I argued in The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing is a Way of Thinking, in order to convincingly represent peoples of Irish and African descent without reducing them to racist caricature, Ware simultaneously employs and challenges Swiss artist Rodolphe Töpffer’s theory of comic art as a study in the pseudoscientific practice of physiognomy—or the divination of a subject’s moral and intellectual character through careful reading of combined facial or bodily features. Because the principles of comic art rely on easily comprehended images rooted in both visual stereotypes and physiognomic logic, Jimmy Corrigan is Ware’s attempt to successfully represent racial difference while working both within and around the limits of the comics language.

If Jimmy Corrigan is a comic about men and representations of race, then Building Stories is about women and representations of sex and gender. As such, Ware’s attention to the principles of physiognomy have turned corporeal, centered almost compulsively on the female body. His protagonist is singularly obsessed with her body’s shape and size, an attention that is often expressed as self-loathing. Women’s bodies are everywhere in Building Stories: the protagonist’s childhood, young adult, pregnant, post-baby, and middle-aged bodies; her landlord’s youthful and elderly bodies; the bodies of the protagonist’s friends, including her best friend, Stephanie, who is recurrently mocked for being “fat”; the body of her downstairs neighbor, who in middle age has developed “child-bearing hips … without bearing any child”; and the infant body of the protagonist’s daughter, Lucy, blown up to an enormous size in the middle of a page.

Yet it is the body of the protagonist that we are asked to consider most frequently, with her pear-shaped silhouette, narrow, slightly hunched shoulders, full breasts, round buttocks, large thighs, thick calves, and small ankles. Her body and face are drawn with an eye for verisimilitude, and, to that end, though rendered with the same characteristic roundness, are often provided more detail and specificity than is typical of Ware’s other work. The effect is that we are asked to take her body seriously, and to consider how she makes her way in the world with and in it, to come to understand that her body is a building in its own right. We are repeatedly asked to “read” her body against the grain of her own self-hatred, on her terms and our own simultaneously. While jogging one afternoon, part of her routinely endless and largely fruitless quest for physical perfection, she thinks to herself, “If guys would just not focus so much on what women looked like, the world would be a better place … Men have absolutely no idea the stress women undergo every minute of their lives worrying about how they look.” This comic is, at least in part, Ware’s attempt to bring this to your attention.

Yet it is the body of the protagonist that we are asked to consider most frequently, with her pear-shaped silhouette, narrow, slightly hunched shoulders, full breasts, round buttocks, large thighs, thick calves, and small ankles. Her body and face are drawn with an eye for verisimilitude, and, to that end, though rendered with the same characteristic roundness, are often provided more detail and specificity than is typical of Ware’s other work. The effect is that we are asked to take her body seriously, and to consider how she makes her way in the world with and in it, to come to understand that her body is a building in its own right. We are repeatedly asked to “read” her body against the grain of her own self-hatred, on her terms and our own simultaneously. While jogging one afternoon, part of her routinely endless and largely fruitless quest for physical perfection, she thinks to herself, “If guys would just not focus so much on what women looked like, the world would be a better place … Men have absolutely no idea the stress women undergo every minute of their lives worrying about how they look.” This comic is, at least in part, Ware’s attempt to bring this to your attention.

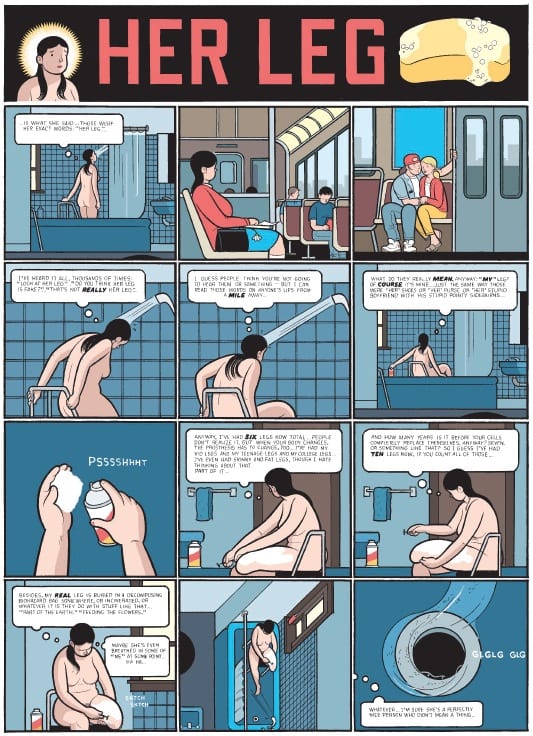

Ware is particularly interested in the protagonist’s naked body, drawing it over and over again as she bathes, examines her vagina in a mirror during sex with her boyfriend, stands before her husband suddenly shy and self-conscious in the moments just prior to coitus, or sucking in her belly in front of a looking glass. At one point, Ware flays her body of its skin and pares it down to its skeleton, an image meant to call forth her favorite childhood book, an encyclopedia with “acetate overlays of the human body that you could peel away.” Diagnosed with a weak heart as a child, the protagonist spent much of her time poring over its renderings of the human anatomy; as a result, the text powerfully affected her understanding of the human body as a child, and is therefore intimately connected to her understanding of embodiment as an adult. Many times, while waiting for her heart to resume normal rhythm after walking up the three flights of stairs to her apartment, the protagonist explains that she “often plays a dumb game, where, by simply concentrating as hard as I can, I try to find exactly where ‘I’ am in my body.” Her attempt to locate her consciousness within her corpus—in her “eyes,” “throat,” “arms,” “legs,” “fingers,” “toes,” “heart,” and “brain”—is structured in the text around the diagram of her skeleton. Yet her efforts to pinpoint the exact position of her “self-consciousness” is futile: “Thing is, I can ‘focus’ on any part of myself, but that’s really just artificial, because as soon as I stop, my consciousness ends up somewhere else … besides, part of me is already gone, and I’m still me … I’m still here, somewhere.” For the protagonist, the boundary of her consciousness is both constitutive of and broader than her corporeal self, part of which—her leg—is “gone.” She has trouble comprehending the meaning of her “self” not only because her limb is missing—“buried in a decomposing biohazard bag, somewhere, or incinerated, or whatever it is they do with stuff like that”—but also because her body schema, informed as it is by studies in human anatomy, does not easily conform to the nonmateriality of “consciousness.” The disconnection between her body schema and her self-consciousness has the effect of leaving her feeling “empty,” and, very often, depressed.

All of this looking at the protagonist’s body is, on the one hand, voyeuristic. There is a sense in Building Stories that you are always looking in on the protagonist’s life, peering at her from a distance or through a window. Even though she largely narrates her own story, she is occasionally written over by an anonymous “editor,” who clarifies her false memories or provides correctives for her frequent hyperboles. That the “editor” can overwrite her without her knowledge establishes a critical distance between her own recollections of the past and our reading of them. Yet, on the other hand, the protagonist is open about her sexuality, and speaks freely about her feelings of sexual ambivalence following the birth of her daughter, for example, or her shame at her ex-boyfriend’s various sexual humiliations. There are very often moments where we are asked to consider her body in deeply personal and non-sexual ways, such as the agonizing physical pain she endures while undergoing an abortion, the sensation of her own weak heart beating in her chest as a child, or the fatigue that attends her deep depression as a young woman. These moments encourage empathy and identification with the protagonist, and, in some ways, mitigate our tendency to fall back on voyeurism as a way of reading.

All of this looking at the protagonist’s body is, on the one hand, voyeuristic. There is a sense in Building Stories that you are always looking in on the protagonist’s life, peering at her from a distance or through a window. Even though she largely narrates her own story, she is occasionally written over by an anonymous “editor,” who clarifies her false memories or provides correctives for her frequent hyperboles. That the “editor” can overwrite her without her knowledge establishes a critical distance between her own recollections of the past and our reading of them. Yet, on the other hand, the protagonist is open about her sexuality, and speaks freely about her feelings of sexual ambivalence following the birth of her daughter, for example, or her shame at her ex-boyfriend’s various sexual humiliations. There are very often moments where we are asked to consider her body in deeply personal and non-sexual ways, such as the agonizing physical pain she endures while undergoing an abortion, the sensation of her own weak heart beating in her chest as a child, or the fatigue that attends her deep depression as a young woman. These moments encourage empathy and identification with the protagonist, and, in some ways, mitigate our tendency to fall back on voyeurism as a way of reading.

Our attention is drawn all the more sharply to the protagonist’s physical body and her negotiation of space because she is an amputee, having lost her left leg in a boating accident as a young girl. On one page devoted exclusively to her leg, the protagonist sits on a shower chair while shaving, and explains how her prosthesis functions as an extension of her body: “I’ve had six legs now total … people don’t realize it, but when your body changes, the prosthesis has to change, too … I’ve had kid legs, and teenage legs, and my college legs … I’ve even had skinny and fat legs, though I hate thinking about that part of it.” As we watch her navigate stairs with a wrist crutch, hop across her apartment floor on one leg, or wrap her leg in preparation for putting on her prosthesis, we are continually asked to consider the ways in which her disability impacts her day-to-day experiences. There are moments when her life is expressly complicated by her missing limb; during an abortion, for example, because her leg does not fit in the stirrups, a nurse is required to hold it in place during the entire procedure. Yet the protagonist is no victim, and we are not asked to pity her not only because she does not feel sorry for herself, but because there is no need.

It is easy to focus on the aspects of Building Stories that are readily apparent—the materiality of its utterly new book form, the complicated architectural panel structure of its pages, or its exacting history of buildings in Chicago. There will be plenty of reviewers who will examine those aspects of the comic, but I want to make the case that the narrative and plot-based elements of the story are just as important to our understanding of the work. Building Stories is in a very primary sense a comic about women and the private lives they lead, and it investigates more fully than any other comic I have ever read the way they age, fall in love, explore their sexuality, come to terms with compromises they’ve had to make as they’ve grown, accept their limitations, confront squandered ability, have children (or choose not to have children), marry (or stay single), and make sense of the world around them. Indeed, even the building that receives the most attention (and is rendered four times over on a large, cardboard foldout), endowed with its own memories and partialities, much prefers its women to men: “With the ladies, life is a picture hung on a nail that was already there … They’re my little birds, bathing, breakfasting, and planting their broad backsides wherever they please.” It is worth considering, then, how the various representations of women are central to our understanding and interpretation of the comic, in both its narrative and material aspects.