As often as baiketsu was covered in the early 60s, and as shocking were the images of human degradation it offered, “there was almost no public response,” recalled the Yomiuri’s Honda Yasuharu, the reporter most committed to the topic. “Since it’s San’ya we were talking about, people probably read about what happened there as only belonging to a remote world, unconnected to our own.” That mental block was breached in the mid 60s, when the discourse on baiketsu suddenly shifted from underclass degradation to mass contamination.

In 1962, a group of medical students from Waseda University went undercover to report on the conditions in places like San’ya and, the main day labor market in Osaka, Kamagasaki. The living conditions of the poor bothered them. But their real motivation was the prevalence of jaundice cases amongst recipients of blood transfusions during surgery. As Mizuki’s first Kitarō story indicates, with its contaminated patient, this issue was already in the public air in 1960.

American blood banks were notorious for buying blood from the urban poor, who suffered high rates of infectious diseases due to poor health and needle swapping. But American horrors paled in comparison to those in Japan. Hygiene was generally a low priority at blood banks in the country. More problematically, so was concern about contamination. Blood density was checked, but nothing else, with disastrous results. The blood industry in Japan was so dependent on unscreened purchases that a hospital patient requiring a transfusion was essentially resigned to hepatitis infection, the rate ranging from 10 to 25 percent across the country, and reaching as high as 65 to 95 percent at some Tokyo hospitals. Dr. Murakami Shōzō, head of the Red Cross in Japan, gave a name to this problem: “yellow blood” (kiiroi chi). The name was meant to capture the discoloration that results from a low concentration of red blood cells (a sign of overselling), but it also resonated with the jaundice that was one of hepatitis infection’s most obvious symptoms.

Following their fieldwork, the Waseda students formed the Japanese Red Cross Students Association and began touring campuses for blood donations. Smart about tactics, they first recruited cute girls. “Because if you get nice looking girls,” explained one of their leaders, “then the boys will also come.” From handsome young people, they moved on to politicians (future Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro was reportedly the first parliamentarian to sign up) and then to movie stars (females first again). More students followed. Red Cross groups were formed at various campuses across Japan. The fight was also taken public. The student activists published damning pamphlets about baiketsu in San’ya and Kamagasaki. The leader of the Tokyo group frequently assailed officials in the city and national government with questions about what they were doing about the situation. The leader of the Osaka wing went on television and described in graphic detail, for an audience of housewives, the aggravated situation in Japan’s slums and the culpability of the blood banks. In 1963, the Japanese Red Cross, for many years alternating reluctantly between “donation days” and “buying days,” announced that it would henceforth operate on a donation basis only. Donations across the country rose slowly, but still were a drop to the rivers being channeled by the commercial firms.

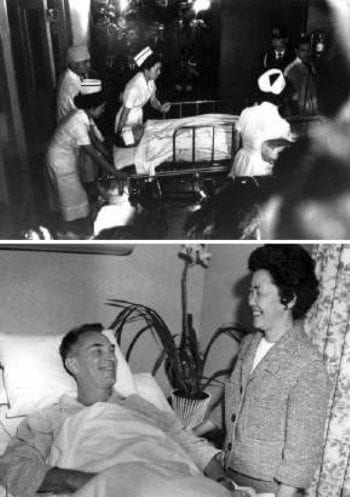

Then came the “Reischauer Incident.” In March 1964, Edwin O. Reischauer, United States Ambassador to Japan, was attacked at his embassy’s entrance by a man with a long kitchen knife. As Reischauer recalled in his autobiography, the man “plunged it straight into my right thigh, where the tip broke off against my thigh bone.” After tying a tourniquet to his leg, Reischauer was rushed to nearby Toranomon Hospital, one of Japan’s best, where he received large transfusions of blood and plasma. “After my second round of transfusions, I issued another statement to the effect that I felt all the closer to Japan because I now was of ‘mixed blood,’ which pleased the Japanese public.” But while recovering in Hawaii, the newly consanguineous ambassador developed a dangerous fever stemming from a liver infection. At Toranomon, Reischauer had been injected with large doses of gamma globulin in order to combat potential diseases in the transfused blood. It was not enough. The blood was intensely contaminated. In 1990, the former Ambassador to Japan died at his home in Boston from complications related to hepatitis. The Japanese blood banks that once saved his life had been slowly killing him.

Thus began the “Yellow Blood Scare” (kiiroi chi no kyōfu). Reischauer’s illness caused a far greater stir than the failed assassination. Commercial blood banking, which was already in the crosshairs for questionable business ethics, was now suddenly a serious political issue. Reporters and medical activists hounded pharmaceutical companies. Ishikawa Gan, one of the earliest reporters on baiketsu with his 1960 article on the Katsushika Plant cited above, threw himself back into the issue with a series of stinging articles for Asahi Shinbun. The issue was even more aggressively covered by Yomiuri reporter Honda Yasuharu, who had been covering blood-selling in San’ya since 1962 after being tipped off by the Waseda students. Honda also spearheaded the “No More Yellow Blood Campaign” (Kiiroi chi tsuihō kyanpeen), begun soon after the Reischauer Incident and continuing until 1967. It aimed for nothing less than the eradication of baiketsu and the achievement of a 100 percent donation system in Japan. Blood bank operators were naturally reluctant, arguing that buying blood was a “necessary evil” for a country in which there was a high demand for surgery transfusions but no culture of donation. Even medical professionals and blood specialists were at first reluctant to support the campaign. Many doubted the possibility of a pure donation system in Japan. Unlike Christian countries of the West, they reasoned, there was no deep-seated religious feeling for “charity” in Japan.

But soon things began to change. Newspapers, magazines, and television programs reported widely on the dangers of yellow blood, stressing that donation was not only desirable but urgently necessary. Their tack diverged consciously from the Red Cross discourse of yore. “What we need now,” wrote Honda in 1964, soon after the Reischauer Incident, “is not just to return to the debating points of humanitarianism and love. The issue is far more pressing than that. Recently a number of people have had their health robbed by bad quality baiketsu, and they may lose their lives. If you are concerned about personal issues, this is one. An issue of a remote world, baiketsu is definitely not.”

With the exploitation of the poor now a middle class concern, the pro-donation movement suddenly found a following. While newspapers hammered upon the commercial blood industry, Red Cross activists increased their activities on campuses and in cities. College students began lining up in greater numbers, setting an example for the general populace to follow. A point was made to have collections conducted in public, so as to familiarize people with the practice of giving blood and bring the practice out of the shadows of the for-profit blood banks. The Ministry of Health and Welfare was petitioned to reform its blood policies, which it did incrementally as donations climbed. Prior to the campaign, 2.5 percent of the nation’s stored blood came from donations. Five months later, in October 1964, that number was 10 percent. The Ministry conceded to increase funding for mobile van units and donation facilities, a first step toward making voluntary donations official government policy.

By 1966, the percentage of donations contributing to the overall national blood supply had crossed the halfway mark. Commercial firms switched to a donation basis, diversified their business, or simply closed shop. The biggest corporation, Nihon Blood Bank, changed its name to Green Cross in 1964 soon after public opinion began to shift. Once providing some 60 percent of the transfusion blood used in Japanese hospitals, the company shut down its preserved blood wing in 1966, marking the end of an era in the industry. The selling of whole blood in Japan was phased out before the end of the decade. It was an amazing turnaround in a country where baiketsu accounted for practically the entire blood supply at the beginning of 1964.

Now back to manga.

(cont'd)