In 1960, when Mizuki Shigeru began drawing his legendary Kitarō series for the rental kashihon manga market, he decided to revise that beastly kamishibai child not only through the dynamic visuals of American horror comics and his own distinctive brand of smart-ass humor – these two mediators are well-known – but also against the backdrop of one of postwar Japan’s most sullied industries: blood banking.

In the first Kitarō story, “A Family of Ghosts” (Yūrei ikka), published in the short-lived horror anthology Yōkiden (Tales of the Strange and Supernatural, from Tokyo’s Tōgetsu Shobō), a young salary man named Akiyama arrives to work one morning and is immediately called into his boss’s office. “I want you to look into something,” he is told, “and keep it a secret. You see, ghost blood has gotten into the company’s blood supply. . . Someone who received a transfusion has turned into a ghost.”

With his company’s reputation at stake – it’s a thriving business occupying a multistory building in the heart of booming Tokyo – Akiyama heads out to the hospital that reported the travesty. Sure enough, the transfused patient has become a flesh-covered bag of bones. Technically dead, explain the doctors, yet somehow still conscious and talking.

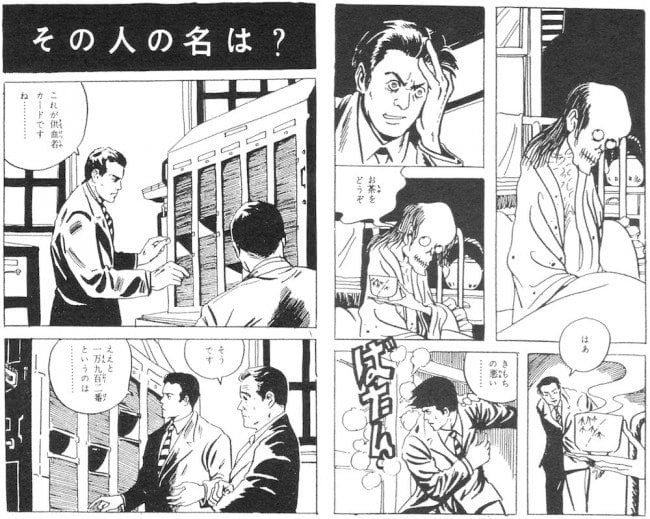

Upon searching company documents to find out who the donor was – unlikely in the real world given actual practices in Japan’s blood banks, as we will see – Akiyama is surprised to discover that the address listed is his own. He questions his landlady about this. She says that she’s seen some strange lights around the abandoned temple at the rear of the property. He decides to take a look.

There, to his eye-popping horror, he finds a Japanese style female yūrei with a forked snake’s tongue and her husband, a mummy imported from American comics (from Bob Powell’s “Servants of the Tomb,” Witches Tales (1951), to be exact). “Please have pity on us, for we belong to an oppressed race [shuzoku],” they plea to the disgusted Akiyama, explaining that their kind was chased into the dark recesses of the earth long ago by the rodent-like proliferation of humans. Ill and without resources to pay for treatment, the female yūrei risked going into town to sell her blood, which was not uncommon for the desperately poor in postwar Japan. Mizuki protests that he must inform his company immediately about the truth behind the contamination, but the mummy makes him promise to remain silent on the matter until their child, the future Kitarō, is safely born.

Underclass contamination of the nation’s blood banks as material for comic horror: Mizuki was not yet done with the motif.

Later that same year, 1960, when Mizuki shifted publishers from the flagging Tōgetsu Shobō to the monied upstart Sanyōsha, he restarted the Kitarō series by elaborating again on dirty blood. Kitarō’s main job, as fans know, is saving humans from the diabolical supernatural. Here, in the first volume of Kitarō Night Tales (Kitarō yobanashi, signed April 1960), Kitarō dedicates himself to the fate of star crooner Trunk Nagai, named after the popular kayōkyoku-jazz singer Frank Nagai. He has, growing out of his right upper arm, the sprout of a plant, the horrible “bloodsucker tree” (kyūketsu ki). It was, without his knowing, implanted inside his body one dark night on a Tokyo city train. This is the doing of the Rat Man (Nezumi otoko), a famous character from the Kitarō universe. Rat Man, as his name suggests, is an oversized anthropomorphic rodent. For our purposes, he is more importantly a stinking, knavish vagrant.

Nagai visits a doctor to have the plant removed. The doctor informs him that it’s too late, that the roots have reached too deep into his arm. Removing the plant would require severing his limb at the shoulder. The matter is somewhat urgent, because everyday this “red tree” (akai ki), as the doctor names it, sucks some 500 cc (just over a pint) of its host’s blood, much above what the body itself can naturally replenish on a daily basis. This is a telling detail, for the number turns out to be a bit over the maximum 400 cc that might be safely taken from someone if they visited a blood bank in real life. As a pop star who depends on his limelight, Trunk Nagai’s career would not be able to survive the amputation of a limb. So he opts instead for daily transfusions to replace the lost blood. To pay for the expenses, he must hand over his performance fees in toto to an agent of a blood bank. “Woe is my fate,” he cries. “I have to work like a beast of burden just to stay alive each day.”

Trunk Nagai survives his ordeal, but ultimately at the expense of his humanity. On stage one night soon thereafter, while singing a typical kayōkyoku tune of tears and male hardship, Nagai turns into a mangle-faced beast (from Steve Ditko’s “Sam Dora’s Box,” Strange Suspense Stories (1954), to be exact). A month later, he sits under an awning in a Tokyo suburb, immobile and in the shape of a gigantic piece of driftwood, before ending up artistically as an avant-garde ikebana display in a swank coffee shop called The Panty at the hands of Sōgetsu School founder Teshigahara Sōfū (a real life person, and a major figure in postwar Japanese culture). Later the driftwood grows a large fruit, from which Trunk Nagai hatches naked and back to his human self. But by this point, Mizuki had moved away from the motif – contaminated blood – that had originally inspired Nagai’s transformation from man into monster.

There is no shortage of vampires in Mizuki’s work, ranging from the obvious Bela Lugosi type to cute little girls and shaggy-haired guitar players whom you would never suspect. However, the origin story of Kitarō and the yōkai hunter’s first task – to save a celebrity from the ill effects of blood contamination – indicates that Mizuki had also been paying attention to the news. As might already be guessed from the above, Mizuki was rather obsessed with incorporating off-handed references to contemporary pop culture, politics, and social issues into his manga. When Kitarō was redrawn for Shōnen Magazine beginning in 1965, many of those references are oriented toward television and tokusatsu – probably because the magazine was dependent on tie-ins with the Braun tube. Meanwhile, in the original kashihon version, it is the poor man’s pulp culture of B-grade movies, American comics, reworked kamishibai and folk stories, and current event scandals that provide Kitarō his field of action. Kitarō might shuttle from the underworld of hell and back, but his point of departure is the everyday of those who, like Mizuki, lived and worked at Tokyo’s lower echelons. Until the mid 60s, the blood trade was an integral and particularly harrowing part of that world.

The city of Kitarō’s birth, in reality as in fiction, was menaced by bloodsuckers. And it is likely that Mizuki, like many other struggling manga authors, knew them personally.

(cont'd)