This is the first in a series of highlights from The Comics Journal’s letters pages (titled “Blood and Thunder”) where many battles raged among members of the comics community.

The grand tradition of the flame war as a snapshot of the pressing issues of the day and as a catalyst for criticism that has its own literary worth is not new. (For the 1730s version, check out Jonathan Swift’s “The Lady’s Dressing Room” and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu’s “The Reasons that Induced Dr S to write a Poem call’d the Lady’s Dressing room.”) At its best, before the Internet was widespread, The Comics Journal letter pages, dubbed “Blood and Thunder”, served essentially as a message board for the comics community. It was a forum where cartoonists, fans, critics, and professionals debated and dissected every development — aesthetic and commercial — in the medium at the time, whether it was the formation of the Direct Market, Creators’ Rights, “writing for the trade,” or “craft is the enemy of art.” (In other cases, they simply trolled each other; the insults in the great R. Fiore/Kenneth Smith showdown got positively Shakespearean.)

Unlike the Internet, however, there was a lag time between provocations, challenges, and proclamations. The effect of this was twofold: 1. Because they appeared in print, and because it took so long to get a response, participants put more thought and effort into their missives and manifestos, and 2. these arguments could — and did — span several months, even years.

In this series of letters, circa 1989-1990, spurred by Leon Hunt’s “Pekar and Realism” piece in issue #126 (January 1989), American Splendor creator Harvey Pekar and critic R. Fiore argue over realism and genre fiction in comics. And Animal Farm.

The first letter, by Harvey Pekar, appeared in The Comics Journal #130 (July 1989):

Comics are as good an artform as any in existence. (How many times have I said that?) Therefore, comics critics should have high standards: a comics work shouldn’t just be good-by-comics-standards; it should be good period. If bad comics are produced, the creators are at fault since the medium they employ allows them as great a range and depth of expression as any other.

But most comics critics and fans have low standards. They like escapist, pulp-derived stuff that will transport them from “mundane” reality into what they believe is a more exciting, glamorous world of the imagination. They crave adventure stories in which life is at risk, where great fame and fotune can be won. Comic book humor tends to be exaggerated; the drawing in "funny" comics stories is generally cartoony. Lately some relatively well-educated comics critics have emerged; they’ve accumulated large vocabularies and claim to have read Ulysses. Unfortunately, most of them like the same dumb comics that ordinary fans adore — for example, they take Frank Miller’s work seriously. These critics attempt to legitimize their rotten taste by relating childish, genre-derived comics to classic mythology and to great non-realist literary works rather than admitting, “Hey, I know this stuff is junk, but I like it.” Most of us like junk of one kind or another; we can’t all have high standards in everything. I like junk food, but I admit it’s junk food. Beware the quasi-highbrow comics critic who tries to tell you Frank Miller and Howard Chaykin write well.

Realism

Many comic book fans don’t like to read about everyday experience; they say such writing is “bo-o-o-oring.” It may also be painful to them; they’d rather fantasize than contemplate their own world. When they become comics critics, too often even the most well-read among them praise and overrate flawed, escapist work.

Leon Hunt recently published a confused, if complimentary, article about me in The Comics Journal [“Pekar and Realism” in #126] that exemplifies the kind of criticism I’ve described above. Hunt said that he liked my work, citing its “fascination,” and that he generally agrees with critics who’ve praised it, but thinks it’s been misunderstood, and sometimes praised for the wrong reasons. Hunt dislikes realism. Most people would claim my stories are realistic and so would I. What Hunt does is cite stories of mine he likes, stories about things I’ve experienced and seen, and then claim they’re not realistic because of the way in which they are told.

His attitude seems to be, “If it’s good, it can’t be realism.” Let me oppose to Hunt’s comment on realism a definition I found in Thrall, Hibbard, and Holman’s Handbook to Literature: “Realism is, in the broadest sense, simply fidelity to actuality in its representation in literature... and in this sense it has been a significant element in almost every school of writing in human history.”

This definition of realism is more viable than the narrowly circumscribed one that Hunt provides. To him it appears that realism equals bad, hackneyed realism.

However, to me “realism” is not simply a school of literature that had its heyday between 1845 and 1925; it is a type of writing that, like “fantasy,” turns up in many eras and takes various forms. It has been argued, for example, that stream-of-consciousness writers are super-realistic because they attempt to convey the thoughts and sensory impressions of their characters so directly. Realistic styles have evolved and are evolving.

That having been said, I still think Hunt’s general description of realistic writing of the late 19th and early 20th centuries is seriously flawed and misleading.

Hunt claims that social realist novels, movies, etc., not only “attempt to record empirical reality as it is” and “people as they are,” but must record “events as they occur” in a linear manner and have “a closed system of producing meaning.” He notes that I don’t always use a linear narrative technique and that some of my stories are open-ended. Therefore, according to his definition, these autobiographical stories are not “realistic,” no matter how accurately the factual data and dialogue in them is presented.

I think Hunt confuses content and style. When he claims realists are concerned with presenting empirical reality, I agree with him, but when he says that realistic works must “record events as they occur” and have “closed systems of producing meaning,” I disagree. I looked at several definitions of realism after reading Hunt’s article; none cited “recording events as they occur” or “closed systems of producing meaning” as essential to realism. Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead is considered a realistic novel, yet in it Mailer departs from recording “events as they occur” and employs flashbacks, which many other realistic writers have done. As for “closed meaning,” Flaubert’s great realistic novel Sentimental Education is open-ended, a “writerly” text that raises questions and stimulates readers to think. Flaubert considered it his greatest novel, but when initially released public reaction to it was cool and it sold poorly, partly because his motives for writing it were not obvious. There are many other truly open-ended realistic novels, for example George Ade’s Doc’ Horne.

This novel contains chapters in which the elderly Doc’ tells a series of stories about his amazing accomplishments that his listeners at a seedy Chicago residence hotel find hard to believe. Still, the reader wonders about Doc’. His articulateness and knowledge imply that he has been more than a skidrow character. And near the end of the book, after a series of humiliations, Doc’ inherits a considerable amount of money from his sister, indicating that once he might have been well connected.

Ade never explains the mystery of Doc’s background, leaving the reader to wonder about it. Perhaps Ade’s major goal, however, is to describe a segment of Chicago’s underclass. This he does vividly and accurately while avoiding, however, making value judgments about his characters. He presents readers with information arid lets them draw their own conclusions. The last chapter of the book merely describes how Doc’, returned from a European trip, finds his companions scattered to the four winds. The novel is deliberately left unresolved. Readers can come to a variety of conclusions about it or none at all.

I believe realistic literature can jump around in time, can deal with multiple themes and points of view, and can be open-ended. Realist works can also be experimental. I have no objection to Ulysses being called a realistic novel; it’s autobiographical and a slice of life, taking place in a short period of time. Joyce’s writing, while experimental, deals with everyday existence. Perhaps it’s no big deal that my definition of realism doesn’t agree with Hunt’s, but beyond this there’s a real difference in our values. Hunt implies that “recording events as they occur” is outmoded. Though I sometimes depart from this practice, I disagree. The linear form is so basic that it’s going to be around a long time. All sorts of writers, including avant-garde stylists, realists, and fantasists, use it, including some Hunt praises. It’s a hard style not to use, especially when dealing with events occurring over a short time span.

Ambiguity or open-endedness is present in many of my stories. But in others I’m didactic, by which I mean that I try to inform, and to render, judgments, sometimes about political and social issues. Many comic book fans don’t like this; they call it “propaganda.” I think the reason they dislike didacticism is because they want to escape from their own and societies’ problems. Didacticism is fine; if writers want to spell out what they think in a novel or comic, it’s O.K. with me. The way they handle it determines whether they’re aesthetically successful, but there are plenty of great works of art in which it’s plain where a writer stands on some issue. We know from reading Germinal that Zola thinks French miners were treated badly, but it’s a great, moving (and not unsubtle) novel. Eisenstein’s left-wing bias is apparent in Potemkin, but it’s considered a great experimental film. Lenny Bruce was an avant-garde comedian who used art to advance his political beliefs, as do many satirists. You can take a stand and still be an experimental artist. Koyaanisqatsi is a highly unusual movie, but its environmentalist message is apparent. Some of the best comics artists — Crumb, Spain, Shelton — make their political positions obvious. But Hunt doesn’t like direct, frank statements of opinion in comics, novels, and film. In listing what he considers realism’s shortcomings, Hunt claims, “Realism is a closed system of producing meaning. For all its varying degrees of ambiguity or complexity, it essentially places us in a passive position as readers or viewers. Regardless of the desire to create confrontation, the effect is just as likely to be reassuring or bleakly despairing, which often amounts to the same thing — neither suggests that change is possible.”

Hunt seemingly considers realism outmoded and clumsy: “Most realist novels and films depend heavily on the economy, the linearity, the identification techniques of classic fiction. They tend to have a visible ‘point of view,’ a discriminative sense of relevance. We are left in no doubt as to why the story has been told.” Realistic writing can be open-ended, as Sentimental Education and Doc’ Horne demonstrate. Not only that, but didactic realistic writing — that is, writing intended to inform and convey opinions — can stimulate readers rather than anesthetizing them. The information contained in books with a “message” obviously can suggest that change is possible. This is so apparent that it leads me to believe Hunt was referring only to certain types of change. However, he never specifies the kinds of change he means. Certainly some didactic novels and short stories have helped, in any event, bring about political change. Their aesthetic quality has varied, but some — like Turgenev’s A Sportsman’s Sketches, which publicized the difficulties of the soon-to-be-emancipated Russian serf — are excellent. Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle helped enact food inspection laws — that is, helped bring about change.

Talkin’ ’bout My Intentions

My intentions are a major focus of Hunt’s article. What do I want to do with the comics form? Well, let me spell it out here. Regarding subject matter: I choose to write about my life and times, as accurately as possible in most cases, to deal with events generally considered mundane, often so mundane that most writers don’t want to make them the focal points of their works as I do. Mundane events, because they occur so frequently, have a much greater influence on people’s lives than the rarely occurring “big” or sensational or traumatic events that readers through the ages have been so taken with.

I write about my life and times because I’m so well-acquainted with them, interested in them, and have more to say about them than about the experiences of people with super-powers parading around in Halloween costumes.

Many of my everyday experiences have, in a general sense, been shared by a number of people, so that they can identify with me and what I write about — if they have the inclination. Everyday situations are sometimes very dramatic; consequently, I have much to choose from when I want to write serious, tension-inducing stories. I can do pieces about getting and keeping jobs, a very important subject. As for heroes, I see them constantly, doing boring, taxing, low-paid work to keep their families going. Regarding humor: I see much funnier things going on at my workplace and in Cleveland’s neighborhoods than I do on TV. In writing about everyday life, I have a huge range of subjects to deal with.

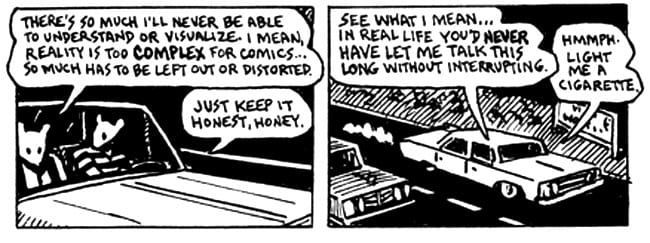

I want very much to be an innovative writer. Dealing with mundane but important subjects other writers ignore is one way I try to do this. Beyond that, I’ve experimented with various narrative techniques, both literary and, in my capacity as an art director for American Splendor, graphic. I’ve asked the people illustrating my stories to avoid the idealized/genericized and cartoony drawing typical of comic book art. Much of the illustration found in American Splendor is realistic; but the realistic styles of Gerry Shamray, Val Mayerik, Paul Mavrides, and Drew Friedman are quite different from each other. Robert Crumb does have a cartoony style, but his work, because of its wealth of accurately observed detail, is also realistic.

Sue Cavey’s graphic style has impressionistic and symbolist qualities. Rebecca Huntington’s beautiful illustration in American Splendor #13 demonstrates how subtle pencil work can be. Kevin Brown’s bold drawing resembles woodcuts. Joe Zabel and Gary Dumm aren’t flashy, but they’re terrific at making their illustration complement a story’s text.

I employ various narrative techniques. Some of my stories are wordy but sometimes, as in “Broken Window” and “Making Lemonade,” I try to tell a story mainly with pictures. Sometimes I use tiers of meaning in my stories and write pieces that have more than one theme, such as “Presidents’ Day.” In “A Marriage Album,” co-written by me and my wife Joyce Brabner, a narrative style is used in which the authorial presence is eliminated and free association, flashbacks, and wordless sequences are featured to create a stream-of-consciousness effect. (I don’t recall any critic referring at length to this story, one of the best, most experimental, and complex pieces I’ve published.)

I frequently use indirect narrative techniques and ambiguity and eschew punchlines, or place the most significant statement in a story somewhere other than at its end.

But in some stories I write didactically, making direct statements to the reader about political and social matters. As stated earlier, there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with this. What the federal government does, for instance, affects our lives, sometimes quickly and significantly. I’m aware of this. I keep up with political events; they concern me greatly. Consequently, I refer to them in my stories. This is perfectly valid, especially in an autobiographical work. The question is how to accomplish this in a fresh, non-hackneyed way. As Hunt notes, one of the ways I do this is by stepping out of my stories to address the readers as an author, not as a character. Instead of eliminating the authorial presence, as in “A Marriage Album,” I emphasize it (sometimes to spell-out and reinforce the point I’m trying to make, and sometimes, as in “Read This,” to create a humorous effect by satirizing the laboriousness of didactic story-telling at its worst — I agree with Hunt that it can be clumsy, as can other types of storytelling). Why not? The stuff I write about really happened. While I employ a lot of fiction writing techniques, I don’t try to disguise the veracity of my stories. Why be cute? Why not write about how political and social issues and problems impact on my life, sometimes jumping out of the story to do it?

What Are Comics Readers Really After?

What do Hunt and most other comic book fans want? Is he really so concerned with stylistic innovation, to which I also give a good deal of thought? Are his artistic standards as high as he would have us believe?

Hunt says approvingly that a modernist sensibility has crept into the work of such commercial writers as Stephen King, as if he believes King is underrated. In an earlier Journal article [“Popular Defective,” #125], he has nothing but high praise for Charles Burns’ horror stories and/or satires of them, never mentioning that in sticking with such stuff Burns, who has ability, is severely limiting his range.

Hunt sneers at Marvel fanboys, but praises what he calls the “estimable” work of mainstream comics writers Steve Gerber, Steve Englehart, and Doug Moench. Maybe these fellows exhibit more modernist tendencies in their work than is generally appreciated, but their stories are not estimable; they’re cliché-ridden. Modernism has been around a long time: Ulysses was published in 1922, Gertrude Stein’s Three Lives in 1909. Obviously, some modernist devices have had time to trickle down to commercial comics writers.

Hunt lauds Frank Miller for “demolishing” the super-hero, when Miller actually worships larger-than-life heroes in his confused way. Why does Hunt like the stories of these Marvel and DC hacks — because of their so-called modernism? I suppose if you wanted to, and looked hard enough, you could find “modernist” elements in a lot of comic book writers’ work. Does Hunt praise it because, although inconsequential aesthetically, the writing of Miller, Gerber, etc., is not the worst of its kind out there? Hunt seems to make a lot of allowances for writers who are doing genre, escapist stuff.

Hunt claims critical response to my work has been so positive that to call into question anything I’ve done would be considered blasphemous. He’s wrong. I don’t win comic book critics awards, like Art Spiegelman (a.k.a. art spiegelman) and the Hernandez brothers, who are treated as icons by their fans. Consider their outraged reaction in letters and articles to the Journal essay I wrote objecting to various features of Maus [“Maus and Other Topics,” #113]. But these people didn’t deal with what I said; they dealt with what they thought I said. Let me answer their objections here, because it relates to what I’ve written above.

Maus Reprise

I have no general bias against anthropomorphism and symbolism, as some readers assumed; rather, I thought Spiegelman handled them clumsily and sophomorically in Maus. What’s the point of using symbols and metaphors when they’re so thin and obvious as to be pointless? Spiegelman’s employment of them in his original 1973 Maus story, which was more of a fantasy, made more sense. There the father was not identified as “Vladek Spiegelman.”

Portraying Jews as mice and Germans as cats, as they are in his Pantheon book — which is plainly a biography and/or autobiography with anthropomorphism arbitrarily imposed on it — is just a gimmick. George Orwell used anthropomorphism in Animal Farm, to which Maus has been compared, but he didn’t identify the pigs explicitly as Lenin or Stalin. Orwell’s work was really allegorical; Maus is not, even though Spiegelman uses symbolism. (I’ve used symbols, too, but I’d rather they be felt than immediately understood. I’m not interested in playing games for the sake of playing games.) Spiegelman has been praised for “distancing” himself from his narrative with his anthropomorphism. What he’s actually done is dilute its intensity and, by doing so, unintentionally make Maus more commercially successful. It’s been claimed that people are inured to the Holocaust by now, that to get their attention with a Holocaust narrative you’ve got to package it differently. That’s baloney. Whenever Israeli politicians want to justify their brutality toward Arabs or ask for support from other countries, they drag foreign statesmen to their Holocaust museum, Yad Vashem, and show them documentary evidence of the horror. After touring Yad Vashem, most visitors are shaken; they haven’t seen cats and mice, they’ve seen real human suffering. People don’t get inured to Holocaust stories; it’s too terrible an event to be taken in stride. Spiegelman’s watered-down Maus, however, is not too painful for them to read.

Spiegelman could’ve used the drawing style he used in “Prisoner from the Hell Planet” in Maus, but that would not have been as arty as employing animals, and he has difficulty distinguishing between arty and artful, and between gimmickry and genuine innovation, as do many comics fans.

Another problem with Spiegelman’s anthropomorphism is that it stereotypes nationalities, which is particularly unfortunate in Maus in that Poles are shown risking their lives for Jews, yet are portrayed by Spiegelman as pigs. Jews were not treated as first-class citizens in Poland, but that doesn’t justify employing a doctrine of collective guilt to implicitly condemn all Poles by picturing them as pigs.

This can lead to embarrassing problems. Chicago cartoonist Carole Sobocinski, a Polish-American, told me that while Spiegelman was autographing a copy of Maus she’d bought for her mother, she asked him how she might explain the Poles-as-pigs metaphor to her mother. Spiegelman disingenuously replied that he’d pictured them that way because Poles eat a lot of pork. (I regret having to use an anecdote like this to make a point, but do so because Spiegelman fans are so worshipful they can’t bear to read anything negative about him. You should hear some of the absurd rationalizations they’ve come up with for his using the Poles-as-pigs metaphor.)

While on the subject of Maus, let me also point out that I didn’t simply object to Spiegelman portraying his father, Vladek, negatively; I objected to Spiegelman’s writing a self-aggrandizing autobiography in which he went out of his way to make himself look good (that is, the long-suffering son) at his father’s expense, emphasizing the old man’s faults to the point of redundance, and de-emphasizing the affection and concern Vladek felt for him. This caused a Village Voice reviewer to conclude that Art was the hero of Maus — “this brave artist,” she called him — and Vladek, who lived through the Holocaust, the villain. Spiegelman claims his portrayal of his father is objective and sympathetic. Actually, it’s fake objectivity. He tries to disguise his hostility to his father. At one point, he shows himself lying to Vladek about not publishing information concerning his father’s early life, but Art says in Maus he’s doing it to humanize Vladek. So we’re supposed to forgive him the lie because he’s improving, humanizing Vladek’s image. Rather than come out and tell us the truth about his loathing of Vladek, Art puts the heaviest criticism of his father in Vladek’s second wife’s mouth. That way, he looks like a reasonably dutiful son and Vladek gets trashed.

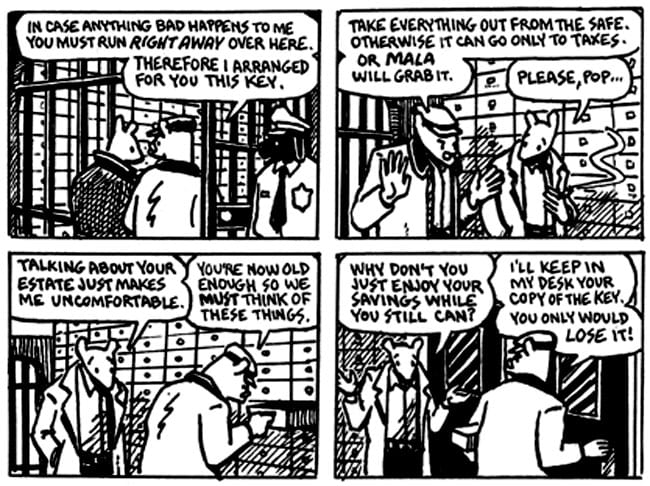

Even when Vladek does something praiseworthy, Art sometimes negates it. For example, Vladek takes his son to a bank to show him a safe deposit box containing precious objects for Art to have in case of an emergency. But the emphasis in the scene is not placed on Vladek’s generosity but on his love of money, craftiness in hiding valuables from the Germans, and on his hostility toward his current wife Mala, who he denounces as mercenary: “Three times already she made me change my will. She wants that I should give nothing for my brother in Israel and nothing for you.”

I’m not saying this event didn’t happen, but Art describes it in such a way as to emphasize his father’s irrationality, miserliness, and sneakiness. The generosity and concern Vladek exhibits toward Art are buried.

Meanwhile, Art puts himself above the fray, makes himself appear a father to his seemingly childish father as he tries to calm him, saying, “Come on, Pop, Mala’s O.K.”

But is Mala O.K.? Is Vladek wrong about her? She calls Vladek “cheap,” “more attached to things than people.” When Art says Vladek may have been twisted by his concentration camp existence, Mala claims that no one she knew that’d gone through the camps was as rotten as Vladek. And yet having known him for years and presumably thinking he was a jerk, she married him. Why? For his money maybe? Maybe Vladek’s right about Mala. “Why,” to quote from my earlier article, “is Vladek shown to be a crazy, petty, tyrannical miser at the beginning and end of two thirds of Maus’ chapters? What is the reason for this overkill?”

It’s probable that Vladek had faults as a father, the kind of faults many Eastern European Jews exhibited when they tried to impose their values on their kids in America, not realizing that the U.S.A. isn’t Poland. However, Vladek also had virtues as a parent. Art seems to have manipulated the facts in such a way as to put Vladek in a bad light while making himself appear sympathetic. Vladek is a complex person. Whatever his motivation, Art’s done a poor, confusing job of portraying him.

It doesn’t matter, for aesthetic purposes, whether Art likes his father or not; what I criticize Maus for is its artificial, contrived, and pseudo-intellectual qualities.

How do I explain Maus’ popularity? Well, for one thing, Vladek’s Holocaust narrative is compelling and full of interesting details. That alone makes the book worth owning.

Also, most people in the U.S. and Europe are so sympathetic to victims of the Holocaust that anyone who writes about them with any competence gets credit for being profound and a great humanitarian. You think I’m kidding? Check out the case of Elie Wiesel, a Holocaust survivor who’s written a number of books about his experiences that are moving but not moreso than other Holocaust narratives, and, even though he’s not a great writer or brilliant philosopher, has been given a Nobel Peace Prize for constantly bringing attention to the Holocaust so the world will not forget it. However, Weisel has been criticized by left-wing Jews for not speaking out against Israeli persecution of Arabs in greater Israel, which leads me to believe that, rather than being a paragon of virtue, he is merely a Jewish nationalist. You see, and I say this as a Jew myself, not everyone who has survived the Holocaust or is related to a survivor is holy.

Because he’s dealt with the Holocaust, Spiegelman gets credit for being more skillful and humane than he is. Kim Deitch tried to defend him in an interview [“Kim Deitch,” Journal #123] by saying, with regard to my statements concerning cheap shots Spiegelman took at his father, “I thought he [Pekar] took it too seriously. All of Artie’s bickering with his father Harvey took as some kind of attack, whereas I felt it was done with real affection... Jews thrive on bickering. .. All of this bickering goes with the territory of being Jewish. [Laughter]”

Deitch’s statement is wrong. In Maus, Spiegelman writes about his having been in a mental institution, about his mother committing suicide, and about his lather’s bitter quarrels with his current wife, who denounces him viciously to Art. This is clearly not a Jewish family that thrives on bickering.

Comic book fans like Maus, in addition to reasons cited above, because it is an adventure story involving Vladek’s attempt to keep himself and his wife alive, to elude the Germans. They also love the anthropomorphism. To these fans, getting Jewish mice and German cats in an adventure story considered “serious” is like having their cake and eating it. They always knew comics were great and now their opinions are being verified.

Los Bros Considered

The reaction of comics fans to the Hernandez brothers is also interesting. I like their work; in fact, I wrote an introduction to a trade paperback collection of Gilbert’s stories, and I stand by every comment I made in it. It ought to be realized, though, that Jaime and Gilbert have their limitations. They certainly don’t outclass some of the best 1965-75 underground comics artists like Crumb, Shelton, Justin Green, Frank Stack, Spain, and Bill Griffith. Although Gilbert’s work differs from Jaime’s, both tend to employ characters that are idealized and/or genericized. Luba, for example, conforms too much to the hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold type, even though she’s a banadora, not a hooker. Maggie and Hopey are just too hip and perky — even when depressed they exude perkiness. They’re romanticized versions of real people.

The work of both Gilbert and Jaime lacks the intellectual richness of Spain or Crumb or Stack. Spain is plenty street smart, and he’s familiar with several street cultures. But beyond that, he’s well-read, he’s interested in politics, and his knowledge comes through in his work, makes it something more than just good popular art. Spain’s lower- and working-class people are seen by him in a larger overall perspective.

So why do today’s comics fans praise the Hernandez brothers so much and ignore Spain? I think one reason is that most contemporary comic book readers, people in their teens to 30s, aren’t equipped to appreciate Spain. We’re talking about people who are less interested in politics than any generation of young Americans I’ve seen (and I’ll be 50 this year) or read about since the First World War, and who, from what I can observe, are not well-versed in good literature. A lot of the material that Spain uses, not just in his biographies of revolutionaries but in fictional works like Trashman, goes over the heads of today’s comics fans. It probably disturbs them, too.

The Hernandez brothers don’t transcend the traditional comics idiom the way Spain does. He doesn’t always write heavyweight, realistic stories, but when he does his characters are more individualized than the Hernandezes’, and physically uglier. A lot of comics fans don’t want to deal with Spain’s harsh, unvarnished world; it’s too much like the one they’re trying to escape. I’m not asking Gilbert to do political tracts; however, in his Palomar you don’t get enough of a sense of the poverty and oppression that most Latin American village dwellers must endure. Jackie Gleason’s New York bus driver Ralph Kramden expresses more anxiety about money than most Palomarans, who seem more like working-class U.S. citizens of Latin American descent than inhabitants of rural Latin America. That is, they seem to be modeled on people Gilbert’s known in California. Interestingly, Jaime has dealt with differences between Chi-canos and Mexicans in Love & Rockets #15.

But they, the fans, love Love & Rockets, full of young and good-looking women they can fantasize about, full of young people of both sexes looking for adventures or having adventures, so that you forget some are supposed to have jobs. The Hernandez brothers know a lot about popular comics and movies, but most of these aren’t worth taking seriously. Locas needs more in it than one character who gains weight to give it credibility. Gilbert has written about serial killing and a witch’s visit to Palomar; his writing owes too much to genre literature, and at times it’s melodramatic.

Genre Literature

What is genre literature? It’s commercial, as opposed to fine art, romance and adventure — that is, science fiction and fantasy, detective, espionage, horror, and cowboy — literature. It’s not impossible to write a great novel dealing with these areas. It’s been done. We by Russian author Yevgeny Zamyatin, for example, is an outstanding science fiction novel. Most American science fiction fans aren’t aware of it, though. Zamyatin is a “fine art,” not a genre, writer. His literary style is too advanced and complex for the average SF fan; he doesn’t employ the clichés genre fans are fond of. And writing an adventure story is clearly not his main purpose. We is a futuristic allegory in which Zamyatin denounces the totalitarian and highly regimented societies emerging in his day. (Hunt may not like We despite its modernist characteristics because Zamyatin’s political position can be so easily discerned. Maybe he’d call it preachy.) Acclaimed by scholars of top-notch fiction, We has little to offer the typical SF fan, who doesn’t care about politics but is fascinated by accounts of life on weird worlds, humanoids, and spaceship battles.

Genre novels rely for their appeal on contrived, tricky plots, sensational adventures in which lives, power, and wealth are at stake, idealized protagonists, too-good-to-be-true heroines, and other stereotyped characters. Obviously, they’re very popular. People who don’t take art seriously, who just want superficial entertainment, enjoy genre literature, TV, and movies. And yet genre fiction is derived from “fine art” literature. And most comics writing is, in turn, derived from genre literature, though sometimes not directly. The trickle-down influences can work like this: Ernest Hemingway, a “fine arts” writer (though one I have serious reservations about) influences hard-boiled detective writers, who influence adventure movie writers, who influence comic book writers, who influence worse comic book writers. By the time you get to the bottom level of these writers, they’re using nothing but solid clichés.

Genre writing is mostly schlock writing. Schlock is popular; there’s a big market for schlock of all kinds, including schlock comic books. (Almost all comic books are schlock, by the way.)

The Monsters and the Critics

Let’s get back to comic book critics again. I’ve mentioned Hunt, who likes Steve Englehart, Steve Gerber, and Doug Moench, who thinks Stephen King’s modernism is underappreciated, and who cites the TV show The Prisoner as an example of modernism. (The Prisoner was actually a genre series apparently synthesized from ideas taken from, or similar to, those of Lewis Carroll, Franz Kafka, and espionage novels.) There’s another genre fan, Donald Phelps, who, like Hunt, wrote a complimentary article about me [“Word and Image: Approaching Harvey Pekar,” Journal #97] — “one of the most engaging phenomena to appear among American comic books, Harvey Pekar’s... American Splendor” — but busted his butt trying to find something to complain about in my work. Since Hunt refers to and praises Phelps’ article, and since Phelps is an advocate of genre art who comes on like a highbrow, I’d like to deal with his comments. I suppose I should have done so in a letter to the editor years ago, but didn’t because I didn’t want readers to realize how touchy and vindictive I am. If you’ve gotten this far, however, the cat’s out of the bag, so I might as well go for broke and reply to some of the things Phelps said about my work — stuff I’ve been grinding my teeth over for years. You can skip this section if you want to; I work cheap, so out of appreciation the editor lets me indulge myself. However, if you read it you may find it interesting. Malicious though I am, I don’t put people down in print unless what I have to say is, in my opinion, valid and consequential.

Phelps really has a shaky idea of where I’m at. He credits me with “a loving, witty esteem for genre art” just because a scene from The Maltese Falcon film is shown in the background of an American Splendor panel.

I was exposed to a lot of popular culture as a kid, but that doesn’t make me a Dashiell Hammett enthusiast. You know by now that Phelps is wrong to say I’m a genre art fan. Let me also reveal that I didn’t really see The Maltese Falcon on the night I wrote about; I saw a Marx Brothers movie. But I told Gary Dumm and Greg Budgett to draw a scene from any old movie they wanted to in the background.

Phelps cites Paul Goodman as being among my influences: “I should be genuinely surprised if he did not know of him.” Brace yourself, Mr. Phelps, because at the time you wrote your article I hadn’t gotten around to checking Goodman out. Since then, I’ve read and enjoyed his Empire City, but what we’re supposed to have in common, except for being Jewish, is beyond me.

Phelps seems to view me as a new kid on the block. He adopts a “wait and see” attitude toward me. After all, I was only 45 years old when his 1985 piece about American Splendor was published, and had only been writing comics since 1972.

He praises stories I wrote and Crumb illustrated as “the most alert, clear-eyed, and richly attentive observations of black people in the daily professions that I have encountered in the work of white authors.” But he claims he’s detected a bit of patronizing toward Crumb in my assigning him these stories. What nonsense! First of all, the stories Crumb’s drawn for me involving major black characters amount to far less than half the work, in terms of pages, he’s illustrated for American Splendor. Beyond that, I have more daily contact with black people than members of any other ethnic group. I’ve always lived in or near neighborhoods with large black populations and worked mostly with black people, and I evidence this in my work, quite understandably. Phelps criticizes Crumb for accepting some of the pieces I give him to illustrate, implying that he’ll get into a rut by doing them. But the fact is that Crumb’s work for American Splendor includes some of his best and most unique illustration. Phelps has cited his wonderful drawing in “American Splendor Assaults the Media,” which contains some brilliant page layouts. To this I’d add his amazingly subtle drawing in “The Harvey Pekar Name Story,” which Hunt praises to the skies, and his outstanding work, employing a brush, in “Hypothetical Quandary.” This is the first time he’d published anything using this technique, by the way. Another stunning piece of work is his drawing in “Pa-ayper-reggs!!”

Phelps patronizingly advised me in his essay to guard against getting too "sentimental" in my work. Where he got that idea was that I’d deliberately pictured myself as self-pitying in a few of my stories dealing with a time in my life when I was single, lonely, and losing lots of money on American Splendor. Since 1983, my life has improved quite a bit; consequently, I’ve cut down considerably on the kvetching, although I’m certainly doing some here. Anyway, I stated in one of my stories in American Splendor #8, “I don’t wanna exaggerate though. I have the advantage over those funky Victorian writers in one big way, so y’don’t have to feel sorry for me. (However, I’d appreciate as much pity as you can give me.)” Shit, wasn’t it obvious that I was highlighting another in my panorama of faults? People think it’s O.K. to show myself as cheap, sloppy, and bad-tempered, so why not self-pitying? Many of us do pity ourselves, at times with some justification. To portray myself honestly, especially at that time, I sure couldn’t suggest that I was a stoic. But Phelps apparently thinks I intended my despairing thoughts to be considered as a body of philosophy — he talks about an internal monologue of mine as a meditation on the “What’s It All Mean” theme. Do I sound like a sentimental guy here? Actually, I’ve made it a point to avoid sentimentalism and romanticism. People describe my work as “grim” and “gritty.” In my story “Rip-Off Chick,” which Hunt wildly misinterprets, a major theme concerns my view that friendship is based on mutual exploitation. Does that sound sentimental?

Let’s consider Phelps for a minute, the fellow telling me to guard against sentimentality. Does he have tremendously high standards? No, he doesn’t. He once wrote an article for Zat magazine praising Little Orphan Annie very highly, claiming it was some kind of masterpiece. Baloney! Little Orphan Annie by the near-fascist Harold Gray is interesting as a period piece and a document of Gray’s craziness, but it has no literary merit. Phelps has nerve charging anyone with sentimentality or with being in danger of falling into a rut when his hero Gray was so corny he was unintentionally funny, and very repetitive, using the same plot devices year in and year out for decades.

I admire a lot of comic strip artists from the 1900-1950 period, including Winsor McCay, J.R. Williams, Elzie Segar, Gene Ahern, and Frank King. But Gray — don’t make me laugh. His stuff is aimed at people with the intellects of children (they are always in abundant supply), like himself.

Phelps and Hunt sling around the names of lots of writers and artists to let everyone know they’re knowledgeable and mean to be taken seriously. If only they could think better. Check out Hunt on Maus: “What Spiegelman has done in his use of funny animal characters corresponds roughly with what the Russian formalists call ‘making strange’... it refers to a process of defamiliarization, transforming the familiar, the routine, the everyday into something new and strange, thereby heightening our perception of it...” The trouble with this statement is that the experience Spiegelman deals with, the Holocaust, is not the familiar, the routine, or the everyday. He could’ve used some non-realistic style to illustrate his Holocaust story, but by employing animal characters he’s not heightening people’s perceptions, he’s watered down the intensity of his work. Comparing Spiegelman to Russian writers who empty ostranenie, or “making strange” (including Nikitin, who, in Daisy, wrote about a tigress from her point of view), doesn’t serve any useful purpose, though it lets Hunt display his erudition. A good example of ostranenie, or “making the everyday strange,” can be found in Yuri Olesha’s story The Chain, about a little kid who borrows his sister’s boyfriend’s bicycle, loses the chain, and panics, experiencing a waking nightmare. What’s next on Hunt’s agenda, an article about the influence of Krylov’s fables on Carl Barks?

Check these two out: Hunt, who likes Englehart, Gerber, and Moench, takes Frank Miller seriously, and gushes over Charles Burns’ approach; and Phelps, who finds a scene from The Maltese Falcon in the background of one of my stories “hypnotic in its off-hand charm,” and praises Harold Gray in terms more applicable to Winsor McCay.

Hunt apparently wouldn’t mind seeing comics remain in the genre ghetto. Maybe he’d like the average comic book writer to become more technically accomplished, but he doesn’t show any enthusiasm for stories dealing with the real problems of today’s world, perhaps because thinking about them would restrict his imagination’s ability to soar — that is, to escape.

Phelps is in love with genre stuff and may have a hard time dealing with non-cartoony illustration in a comic book; he dismissed Gerry Shamray’s superb illustration in “I’ll Be Forty-Three On Friday” as schmaltzy. Apparently, he wants pies in the face. Even Crumb, who I expected would consider Gerry’s work “too modern” or “too fancy,” likes it a lot, and has used it as a reference for his own American Splendor work.

Anyway — if more comics writers and illustrators don’t get away from genre influences, comics are going to continue to be viewed by the general public as a less-than-first-class art form, because they will so seldom see anything worth taking seriously.

Disclaimer

Now here’s the disclaimer: Some of you will notice that the kind of comic book writing I seem to be championing here, realistic and experimental, is the kind of writing I do. You’ll think that in writing this article I’m trying to further my career. That’s an acute observation — certainly, I’m attempting to do that, among other things. If you detect irritation here because artists and writers whose work I’m not crazy about are getting raves, your mind’s not playing tricks on you. But I strongly believe in what I’ve written here and hope that people who really think comics are a great and versatile medium (as opposed to those who think they can only tell adventure stories) take it seriously.

I’ve been lucky to get so far as I have writing comic book stories that are so alien to comic book fans. Really, I’ve done quite well. But we take things for granted; we get greedy. In six years, I’ll be able to retire. At that time, I’d like to be able to supplement my pension with money earned as a writer. The more non-genre-derived comic books there are around at that time, the better it’ll be for me. Not just realistic comics, but surrealist, impressionist, expressionist, anything as long as it’s not the kidstuff that dominates the market now. Comics need new, more demanding readers for their quality to improve, but to attract them better comics have to be produced. I don’t care which comes first, the chicken or the egg, but I’d like to see this process, involving better artists and writers producing better comics for more knowledgeable fans, catch hold. My idea of better comics is not the 1970s Howard the Duck written by Gerber, or Dr. Strange written by Englehart, or Master of Kung-Fu by Moench; it’s not Little Orphan Annie produced by Harold Gray on the best day of his life.

This is not to say I think junk or schlock comic books like Superman and Batman and Thisman and Thatman should be banned any more than McDonald’s or Taco Bell food should be. They all fill a need; they give pleasure to a lot of people, including many (far too many) who read this publication.

But comics can be, and occasionally have been, more than that. There are tons of bad genre novels and movies produced every year that account for a huge percentage of their respective markets. But enough high-quality novels and movies are done to attract talented, uncompromising artists to these media. Gifted writers and illustrators may never encounter a good comic book, however, and consequently will assume it’s impossible to create one.

Hunt concluded his article by claiming he wanted to initiate a discussion about my work. It’s been a pleasure to join such a discussion; I could go on for many more pages, but I don’t want to continue offending all the Marvel and DC comic book readers out there, the ones that cause The Comics Journal to waste space on super-hero publications, the ones that make Fantagraphics publish Amazing Heroes so that they can earn enough money to print good comics that don’t sell.

I hope, however, that a few readers find this

article enlightening. To them I say: Remember,

I also make a very fine pepper jelly.

Continued: R. Fiore's response