The "Craft is the Enemy" debate, which ranged over several years, several issues, and several continents, began with a letter by James Kochalka (American Elf) in The Comics Journal #189 (in 2005, Kochalka would expand on his theory in The Cute Manifesto). Some readers found this letter inspirational; others, notably Jim Woodring, wrote in refutations.

From The Comics Journal #189 (August 1996)

CRAFT IS THE ENEMY

JAMES KOCHALKA

Burlington, Vermont

I'm not exactly sure why I'm writing this letter, but I've been reading TCJ #188 for a couple hours now and my mind has just been racing and blood pounding. My excitement with the power and possibilities of comics mixed with the fear of a royally screwed-up marketplace... well, let's just say I've got a weird, shaky adrenaline rush.

I just felt suddenly like I had to write and say craft is the enemy! You could labor your whole life perfecting your "craft," struggling to draw better, hoping one day to have the skills to produce a truly great comic. If this is how you're thinking, you will never produce this great comic, this powerful work of art, that you dream of. There's nothing wrong with trying to draw well, but that is not of primary importance.

What every creator should do, must do, is use the skills they have right now. A great masterpiece is within reach if only your will power is strong enough (just like Green Lantern). Just look within yourself and say what you have to say. Cezanne and Jackson Pollock (and many other great painters) were horrible draughtsmen! It was only through sheer will power to be great that they were great. The fire they had inside eclipsed their lack of technical skill. Although they started out shaky and even laughable, they went on to create staggering works of art.

This letter is not for the established creators... they're hopeless. This letter is for the young bucks and does... let's kick some fucking ass!

From The Comics Journal #190 (September 1996)

CRAFT IS YOUR FRIEND

JEFF LEVINE

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

I'm surprised to see you printed James Kochalka's near-moronic letter in the latest Comics Journal (#189) regarding craft being the enemy. I might agree that trying to draw well is not of "primary" importance—but at the same time I think it is, in fact, incredibly important! What makes comics a unique medium is the combination of words and pictures — and while a naive artist/writer's work can occasionally be amusing, to advise that technical skill is to be avoided is a ridiculous philosophy.

If you take Kochalka's statement that both "Cezanne and Jackson Pollock (and many other great painters) were horrible draughtsmen" as being true, and that despite that they still made great art — it's horribly bad logic to imply that that means that technical skill isn't worth acquiring or working hard to achieve. I can think of a fuck of a lot more artists who were great draughtsmen, who made timeless worthwhile art, then artists who didn't have those skills whose work is worth studying and admiring. Yes, art doesn't have to always be technically strong to be "good," but it certainly tends to help.

The last thing modern comics is in need of are more naive artists lacking technical skills, when the majority of comics that are currently being published are already so horribly drawn that there's little to be gained by looking at them. I'd be much more interested in a new artist's work that was original and well drawn, that actually had something interesting to say, then looking at a bunch of felt-tip pen poorly drawn comics about elves and robots.

This letter is for all the young bucks and does... learn to write... learn to draw... having a professionally published comic is a privilege, not a right — and it has to be earned. Let's kick some fucking ass!

From The Comics Journal #191 (November 1996)

CRAFT ISN'T A FRIEND

JAMES KOCHALKA

Burlington, Vermont

O.K. I'll say it again in a different way for the idiots who couldn't understand me the first time.

When you're shooting for immortality, anything less than stunning achievement is a failure. Creating a powerful work of art is like running and leaping across a chasm. It takes all of your strength and you'll probably be dashed on the rocks and fall to your death.

Being a craftsman is like sitting in your woodshop all day carefully building a chair and when you're done, you sit on it.

Are comics craft? Well, certainly any cartoonist you are liable to meet will tell you "yes." And that's a big problem. Craft is boring. Ever been to a crafts fair? Not unlike a comics convention. Craft sucks.

When a cartoonist sits down to draw, and their goal is to draw well, they are doomed to failure. No matter how much they practice the best they can hope for is to become a polished hack aping their preconceived ideal of "good comics," to become a mere hollow shell of the cartoonists who came before.

For one reason, there is no objective "good" in art. Someone could conceivably think Spawn is well-drawn and think Peanuts is poorly drawn (although that sounds insane to me). So if you're trying to draw well what you're shooting for is illusory. There is, objectively, no such thing.

However, if you're burning up inside with the need to express yourself, if there's something you desperately need to say, when you sit down at the drawing table you think "How am I going to say this? How am I going to express myself so that people will understand?" The art will be slave to the content. Either the artist expresses the meaning, emotion, and power of their vision or they do not. The comic succeeds or fails on these terms. The notion of quality is meaningless.

From The Comics Journal #192 (December 1996)

ONE IDIOT'S REPLY

JIM WOODRING

Seattle, Wash.

As one of the "idiots" who disagreed with James Kochalka's first anti-craft letter I want to reply to his brazen follow-up.

Kochalka, you are wrong. Craft is control; it is the ability to create according to one's intentions, not in spite of one's limitations. Imagine saying that a writer doesn't need to know how to write, or that an architect need not be concerned with "craft." Well, I can imagine you saying it.

Was your point that craft without content is not great art? Well, no shit. Everyone knows that. Craft fairs not your cup of tea? Tut tut.

To describe Pollock and de Kooning as artists who were great despite a lack of craft is absurd. They may not have been great draughtsmen but they both had oodles of craft as painters, which is after all what they're known for. Both men were obsessed with getting exactly the effects they wanted and they worked like demons to develop their particular crafts.

You say there is "no such thing" as good drawing. Wish it into the cornfield, Jimmy! I've got an idea; why don't you re-draw the pictures of Heinrich Kley, preserving only the ideas. We'll see what role craft plays then.

CALL OF THE WILD

MITCH CARLTON

San Diego, Calif.

I'm ticked off! When I read James Kochalka's letter in #189, it gave me just the kick in the ass I needed to put pen to paper and pursue in earnest writing and drawing the comics I'd previously spent more time daydreaming about than bringing to fruition. Then along comes Jeff Levine's letter in #190 raking Kochalka over the coals for his "near moronic letter."

Jeff, you need to go back and reread Kochalka's letter — you completely missed its point! Nowhere does Kochalka imply that technical skill "is to be avoided," as you put it. What Kochalka was stressing was the importance of cartoonists — of any skill level — saying what they need to say right now instead of forever putting things off — as I'd been doing — until they'd reached some fantasized, far-off plateau of artistic perfection.

Now that we've got that straight, all you young bucks and does, let's kick some fucking ass!

STARVING IN SEATTLE

JEFF JOHNSON

Seattle, Wash.

I don’t know if Kraft is the enemy, but they make a fine macaroni and cheese.

From The Comics Journal #194 (March 1997)

FOLLY

JAMES KOCHALKA

Burlington, Vermont

It may be folly to keep writing back, but oh well. I don't feel too much real need to respond to Jim Woodring's answer to my letter specifically, but it does give me a good starting point to continue and expand on my rant.

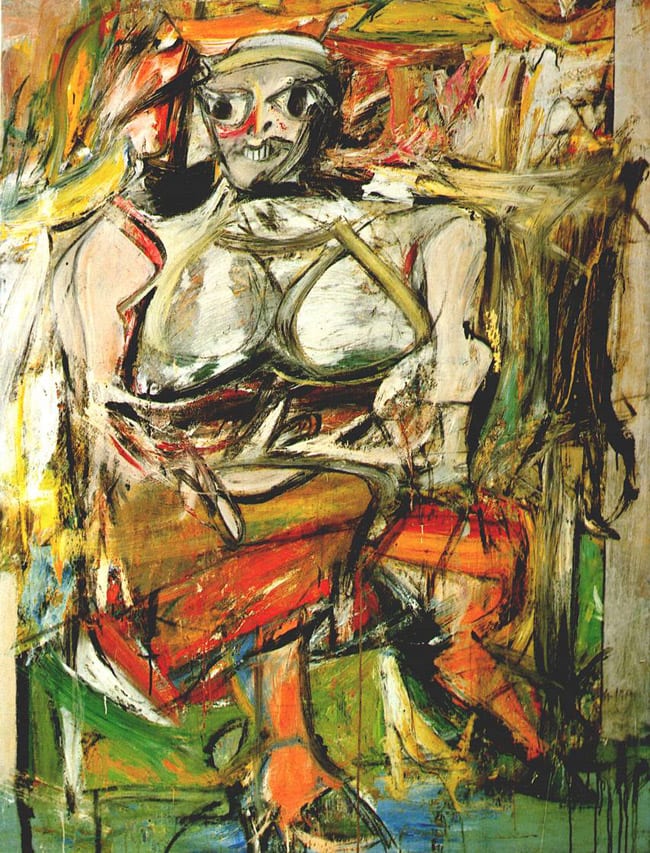

I don't think Woodring read very carefully because I never even mentioned de Kooning in my letter, let alone set him as an example of someone being great despite lacking craft. De Kooning is a craftsman through and through, and a marvelous one at that.

However... his very best painting, the first "Woman," has nothing to do with craft. It was a violent attack, an error, in fact he rejected it and threw it away… luckily a friend rescued it. And it’s got so much more life than his many countless well-crafted works, which get a little boring actually.

Craft allows you to be pretty good most of the time. Which is absolutely useless. The only thing that allows you to be great is taking massive risks.

Craft is knowledge. You perfect your craft, slowly adding to what you know how to do. But great art only comes from risking to attempt what you do not know. No matter how much craft you have under your belt it will not help break the magic barrier to creating a truly great and immortal work of art. Only a complete abandonment of your mental safeguards will allow you to do that. Craft will hinder you, keep you forever tied to the world of the known.

So, while craft may give you tools to express yourself reasonably well, it's just not enough. I'm not talking about "craft without content." I'm saying that craft is not enough to express content in a way that will have any real effect on anyone. For instance, who could better express anger... a professional session musician who is a technical expert, or the punk rock kid who can barely put two chords together? My money's on the punk.

But beyond that even, to get to the real heart and soul of what makes us human it takes a wild leap away from the safety of our conventions, our craft. Craft is a rope tying us to mediocrity of expression! We're all too timid to untie it! "But we've worked so hard to learn how to draw, how to write. We can't give that up. If we untie the rope we'll just float off into space," we whine.

I'd rather fucking choke and die in the vacuum of space than anemically craft a series of smarty pants sequential pictures and pat myself on the back for my skillful accomplishment.

The joy of comics is their stupidity, their simplicity. The way they can cut right to your soul so easily. Just a simple string of symbols and pictures, how can they do that? Magic! It’s magic, pure and simple, not craft. I refuse to accept that the magic of comics is crafted. It comes out of nowhere, I know it.

Yet, at the same time, clearly the opposite is true. Comics is a visual medium, and all there is to see is ink on the page. What we see is processed by the brain and in turn causes an electro-chemical emotional response inside our bodies. The composition within panels, the transitions between them, every minute touch of the brush will affect the meaning of the comic and the reader's response. Can the artists really control all of this well enough to produce the response in the reader that they intend? Especially considering that each reader's response will be tempered by their own lifetime of experience, can anyone possibly predict any of this reasonably well enough to craft a comic that will actually function as they desire it to? And that's assuming that the universe is truly governed by laws of cause and effect. What if things occur randomly?

You don't want to be thinking about any of this crap when you sit down to draw, I'm pretty sure. Better to let it flow out like magic, or lash out wildly like a beast, than to try second guessing the universe well enough to actually craft greatness. I'm sure you'll have little trouble learning how to craft mediocrity, however.

SUPERSTAR?

DUANE PARTON

Houston, Texas

How pompous can James be, to assume that because someone disagrees with him they don't understand his argument. It seems to me that his argument is simply not defensible.

If Burne Hogarth, Neal Adams, or John Byrne were to make the same argument, I might have some respect for their position. Why? Because they have skill and are therefore able to select an appropriate style of art based on the ideas they are trying to communicate. I have never seen any work by Kochalka (the self-proclaimed super-star) to indicate that he has any significant talent. Therefore, his rant against craft sounds to me more like an excuse for his lack of ability than a truly defensible philosophical position.

I simply find him and his work pathetic.

PLAY NICE

JOSEPH CHANG

Singapore

I have been following the debate between Jeff Levine and James Kochalka, as it's an interesting topic for discussion (though the calling of names could be spared).

I think cartoonists can be divided into two camps, namely the 'anti-craft' camp of James and the 'craft-is-important' camp of Jeff. The argument here is whether craft is important to create good comics, or if it actually hinders the cartoonist to create equally good comics.

Let us take punk music as an example. There would not be The Sex Pistols if Johnny Rotten and company had been spending their whole life perfecting their guitar-playing skills in their garage. Without doubt, punk music has since gone on to become an important music movement and The Pistols are considered an influential band by many critics and fellow musicians. In fact, punk even spilled its influence into comics at its helm.

The above shows why craft can be the enemy like what James fear. While being obsessed with perfecting one's craft, one might forget the initial aim, which is to produce good comics. One good example is John Porcellino, creator of King-Cat Comics. It is John's almost child-like art that brings out the charm of his stories. Even Jeff agreed that 'this comic is past due for greater recognition...' (TCJ #192).

On the other hand, Jeff has got a point too in refuting James' point of view. Without the necessary craft and skill of drawing and composition, it can only frustrate the cartoonist who is trying to create a good comic. Unless you're a natural like John Porcellino whose naive art complements his story almost perfectly, the lack of craft can only hinder you to create a good piece of work. I believe it would not be possible to create a work like Seth's "It's A Good Life, If You Don't Weaken" if he did not have the necessary drawing skill to execute it.

I can go on to quote examples of cartoonists who continue to create interesting comics with nothing but sheer enthusiasm and determination (e.g. Mark Beyer), and those who do it with great technical skill (e.g. Chris Ware), but I think the point is, it takes all kinds to make the world. And we need both James' and Jeff's schools of thought in order to have more variety in comics and make comics a continuously exciting medium.

From The Comics Journal #195 (April 1997)

TO THE MOON...

SCOTT McCLOUD

via the Internet

Poor James Kochalka.

I think I know what he was trying to say way back in TCJ #189 with his "Craft is the Enemy" letter, but it got kind of garbled (more due to a deficiency in his command of the "craft" of rhetoric — no dig intended — than a weakness in his basic argument).

There are a significant number of young artists who believe that great work is just the inevitable result of the gradual accumulation of skills and those are the artists J.K. said he was talking to. Maybe he deserved a slap or two for slingshotting [sic] so far in the other direction (and from no less than Jim Woodring — ouch); and I'm on the record saying that craft is an inseparable part of the creative process. But in the real world, a lot of comics artists really do put cold skill on a pedestal, and never make those great intuitive leaps that put those skills in perspective.

There's no way to skip the hard work of learning our craft. But I hope we haven't given anyone the impression that hard work is all it's going to take. Getting from poor to fair to good to great isn't some kind of straight path of incremental steps. If you're working on your skills every day and just assuming that inspiration will come if you work long enough, you could be waiting for the rest of your life.

No one ever reached the moon by becoming a really good mountain climber.

From The Comics Journal #196 (June 1997)

TKO

JOSEPH POOLE

London, England

Like a boxer who has just felt the power of his opponent's punches and realizes he has stepped out of his league, Mr. Kochalka is left defiantly flicking out his jabs in an effort to disguise the fact that, in reality, he is backpedaling.

In defense of his original "rant" and in response to Woodring's criticisms, Kochalka performs a classic textual sleight of hand (TCJ #194). He clumsily shifts the ground of his argument from his original assertion that craft is at best useless and at worst detrimental to the production of great works of art to a new position in which he claims that craft is not everything. Gee, James, no shit. As Kochalka knows fine well, nobody has argued nor would argue with this latter view and if he had initially expressed this view it would have proved to be as uncontentious [sic] as it would have been insane.

And, true to form, Kochalka is soon up to his old tricks again. As one would expect from a nobody who awards himself the status of "Superstar," Kochalka's primary goal is attention and he is clever enough to understand that is something much more easily obtained by spouting simple-minded provocative mumbo-jumbo than by undergoing the laborious task of thinking. As a result, he rapidly lapses back to his former position that "Craft is a rope tying us to mediocrity of expression!" because he realizes this statement will provoke those who admire skill in a way that his earlier, more rational claim that "while craft may give you tools to express yourself reasonably well, it's just not enough" simply would not. For Kochalka, it is far better to be wrong and noticed than right and ignored.

This time when Kochalka returns to his craft is crap stance, it has an interesting addition, however. Not it is accompanied by the kind of quasi-mystical hogwash that one would expect from somebody who thought that philsophy [sic] sounds like a "neat idea" but felt that actually taking the time to read any would be too much trouble. Mechanistic models of human thought are ineptly linked with a vision of a relativistic human subjectivity perceiving randomly in a chaotic cosmos and all in one crazy, rambling paragraph.

Of course, the question of the stability of the concept of the cause/effect relationship was addressed with considerably greater insight by the Scottish philosopher David Hume some two and a half centuries before it stumbled its way into Kochalka's conscioiusness [sic]. However, in his response to Hume's skeptical questioning, Kant demonstrated that while it is possible to partake of the academic exercise of doubting the existence of the cause/effect relationship in the object world its presence in the structures of the human mind cannot be similarly doubted because it constitutes a prerequisite of the act of perceiving itself. Kochalka's theories insofar as they are coherent set us adrift in a world (?) of nonsense in which not only meaningful communication but the very act of perceiving is rendered impossible.

We can see that a certain universality exists between us in our reading of works of art even if we cannot entirely explain it. If there were no commonality in our response to art then why are almost all moved by Hamlet's tragic plight but feel nothing for Liefeld's Captain America. (I confess I have not read the later. I'm just guessing.) If the production of great art occurs by chance alone as Kochalka suggests, why is it that certain individuals such as Picasso, Scorsese or Kafka consistently produce a high standard of work while Kochalka consistently produces mediocrity?

The fact is that craft is not simply the ability to adhere to a set of anatomical measurements, rules of perspective or antiquated schemata, but rather the ability to adequately translate one's vision into its externally presented form. The more accurately the final result matches the idea the artist sought to express the more accomplished the artist's craftsmanship. In order to produced great art, the artist must, as Kochalka repeatedly suggests, have a great vision to express and no amount of craft will make up for a deficiency in this area. Nobody would contest this and in raising it, Kochalka seeks to win a war that no one is waging. Naturally, inspiration, ideas and creativity are crucial components in the production of great art, but without the ability/skill/craft to make such things manifest, one can be a great person but not a great artist. Because to be an artist, great or otherwise, one must produce an artifact and the transition from inspiration to manifestation requires the perspiration of craft.

From The Comics Journal #198 (August 1997)

KOCHALKA’S CRAFT CORNER

JAMES KOCHALKA

Burlington, Vermont

Let's say you're a painter, and one day perhaps you hit upon an interesting way to paint grass that you had never thought of before. If, from that day forward, every time you need to paint grass you paint it in this same manner, then you've become a craftsman. You were an "artist" when you invented this technique, and a "craftsman" when you repeated it.

In this way, every artist becomes a craftsman. You learn to become consistent. There has never ever been an artist who has not lapsed into formula. However, it's the rare flashes of brilliance that we all hunger for, not the consistency. Craft is important because it gets us through the days when we're not brilliant. It can also be a hindrance, because if we adhere to it, it keeps us from that brilliance.

It's funny to me that no one seems to notice that there could possibly be any danger in devotionally adhering to craft. I suppose it could be because the great cartoonists of the past were such strong craftsmen and we think it would be nice to follow in their footsteps. Unfortunately, their footsteps don't lead very far. So fuck them.

Whoops! I promised myself I'd play nice this time. In many ways, the consistency of craft is quite valuable, especially for comics. There's a cumulative power that grows page after page in a comic that is consistently crafted to conform to a particular mood, for instance.

It's a very tricky business, though. To utilize the power of craft, without suffocating and killing your work. Craft can be a crutch which keeps one from making his next exciting discovery.

SILLY, SILLY MAN

JOUKO RUOKOSENMAKI

Tampere, Finland

It is very likely that by the time I finish typing this letter and get it mailed you may very well have chosen to abandon this rather silly conversation sparked by James Kochalka's attacks on the craft of cartooning. As it stands, I read his latest missive (in TCJ #194) just a few moments ago and felt sufficiently pissed off by his claims to write to you.

I am what you might call an "amateur cartoonist" (not that there are that many professional cartoonists in Finland, but that's another story). I have drawn comics for the last 15 years, and I have been fortunate enough to have gotten most of my work published in Finnish fanzines. I draw mainly for my own amusement: if people like the stuff that I produce, fine; if not, well, I really don't give a shit. When I draw, I'm mostly concerned with what Kochalka would label as "craft." My object is to make illustrations come out as I intended them to be, not to produce some great and meaningful works of art by accident. I can, however, understand the other point of view: some cartoonists might have an irrepressible need to communicate with their audience, and they think that craft gets in the way of this. To claim that this is the one, true way to make comics is, of course, bullshit. In the end, it is just a question of taste, not about who is right and who is wrong.

As Kochalka has seen fit to compare comics artists with musicians, I guess I should continue that line of thought. Kochalka says that a "craftless" punk rocker can express anger a lot better than someone who actually knows how to hold a guitar. Bollocks to that. Punk was, is and always will be just a marketing gimmick. The music of the "great" punk bands of yesterday did not have any staying power or real values. Oh yes, DJ's all over the world are still playing "God Save the Queen" and the serious rock magazines are praising its importance. But when the Sex Pistols finally do a reunion tour, what happens? They get booed off the stage. What's the matter? If the music is that great, surely it should still work live, even if the musicians are already middle-aged beer-bellies? To get a good impression of how anger is expressed with a guitar, I advise Kochalka to listen to King Crimson's Red from 1974. Robert Fripp plays with real craft, yet his tunes are more chilling than anything Steve Jones ever got out of his guitar. And when you listen to KC's version of the same song in 1995 (B'Boom-live), it still sounds chilling. And even the audience is cheering. This is craft at work.

Mind you, I don't think that you can compare comics with rock music that painlessly. Still, I'm pretty sure that Kochalka cannot stand bands like King Crimson: again, it comes down to the question of taste. It's useless to say that the Sex Pistols suck because they are not "crafty" enough. Likewise, claiming that KC suck because they are excellent players does not lead anywhere. Just for the record: I have never read any of Kochalka's comics, and I pray to God that I never have to.

(By the by, I'm sure that I do not have enough "craft" in the English language to express myself as fluently and wittily as the other writers in your splendid letter column do. Does that then make my letter a serious work of art or what?)