Some more notes on race and comics. Although the notes deal with this issue from a variety of angles, one topic that I keep returning to here is the question of black readers of the comic strips.

The Big Picture. “The cartoonist’s craft is by its nature a conservative, perhaps even a reactionary one: its very essence consists in the manipulation of shorthand visual signs and widely recognizable stereotypes.” Art Spiegelman, “A Real Eye-Opener", foreword to The Unexpurgated Carl Barks (Hamilton Comics, 1997).

Harold Gray, Racial Progressive. One of the things I’m trying to do with these notes is to move beyond the cliché that “everybody was racist back then” and try to show that there was actually a spectrum of racial attitudes among cartoonists. Evidence of this spectrum of attitudes can be seen in the aesthetic choices that they made. One good example of this is Harold Gray, who despite his reputation as a reactionary was a robust critic of ethnic bigotry and nativism.

Gray’s opposition bigotry could be seen most clearly in the issue of immigration: Gray created Little Orphan Annie in 1924, a high-water mark for nativist sentiment. It was the year Congress passed a severely restrictive immigration law, and the second wave of the Ku Klux Klan, which targeted “un-American” groups like Jews and Catholics, was at its peak. From the very early days of Annie, Gray was critical of nativist sentiments and made sure that the orphan star of his strip would befriend Americans from all different ethnicities. One of Annie’s earliest friends was an Italian American boy named Tony DeBella. Later Annie would befriend Jewish-Americans like Jake the shopkeeper (who would employ Annie in the early days of the Great Depression) and the Irish-American Maw Green (who ran a boarding house Annie and Warbucks lived in when they were down on their luck in the early 1930s).

In light of the Spiegelman quote above, which quite rightly notes that “widely recognizable stereotypes” are part of the core of cartooning, it’s worth underlining that in taking an anti-bigotry stance in his comics, Gray doesn’t eschew stereotypes but rather repurposes familiar ethnic tropes in a positive way. Jake, for example, is careful with his money and a hard-bargainer, but in the context of the Great Depression these are shown to be essential character traits that keep his business going. Maw Green, like her Irish-American sister Maggie from Bringing Up Father, is a tough-talking broad, but, again, that makes her a good friend to have if you’re a luckless orphan: Maw Green is tough enough to back you up in any fight. Gray’s customary tactic in dealing with ethnicity is to rework standard tropes and turning them into positive stereotypes.

Annie and Tony. Annie’s friendship with Tony DeBella is worth looking at in greater detail because it shows how Gray integrated his pro-immigrant message within the comic. In late 1925 and early 1926, Annie is under the care of the prissy, dishonest Mrs. Sandstone. Bored by Mrs. Sandstone’s gentility, Annie takes a walk in her old haunt, Tin Pan Court, a bustling tenement street. There she meets here old friend, Tony DeBella. Annie visits Tony in the small apartment where his family lives and delightfully eats Italian food: “Oh baby – ravioli – I haven’t had any real ravioli or spaghetti since the last time I was at your place.”

The next day Mrs. Sandstone tells Annie that she is lucky to be living “on a respectable street” rather than “that terrible Tin Can Court,” which is filled with “such a rough, illiterate foreign element. Trash. I’m so glad we don’t come into contact with them.” After she gets away from Mrs. Sandstone, Annie voices objection to what she’s heard: “Where does she get that stuff. Trash. Foreigners. They’re swell people, they are – and tin-can court’s got this drag we live on licked to a frazzle.”

Soon thereafter, Annie discovers that Tony’s family is having trouble. Sam, the father of the family and a janitor, had been framed for a crime and is now in jail. Annie’s appeals to Mrs. Sandstone for help but the older woman objects to orphan hanging out with “foreigners” and “criminals.” The DeBella’s have a lawyer, Mr. Flam, who promises to help free Sam DeBella. Unfortunately, as his name indicates, Mr. Flam is a Flimflam artist.

In desperation, Annie turns to Paddy Cairn, the local ward boss. Cairn is a type of character who would recur often in the strip: a Warbucks-substitute who helps Annie when her adopted father is away. Like Warbucks, Cairn is a barrel-chested mesomorph as well as being a tough-talking regular guy. Annie notices the similarities between Cairn and Warbucks, observing ““gee you always make me think of ‘Daddy’ Warbucks.” As it turns out, Cairn and Warbucks had been “kids together in the old eighth ward.”

One of Cairn’s cronies don’t want to help Annie and the DeBellas, saying, “Aw, why fool with dem wops? Wot can a bird like that guy ever do fer you? Lay off dem ferriners.” Annie of course objects to this ethnic slur and attacks the crony, kicking him and yelling: “Wop, is it? I’ll wop yuh one on th’ nut, I will – buttin’ in when Mr. Cairn an’ a lady are talkin’” Cairn’s calms Annie down and offers his help, saying, “I’m for you, see? But don’t cripple ‘em on the premises. And that foreigner stuff is out with me too, Annie. Breed or creed or doesn’t count with regular folks. We’ll get the straight on Tony’s dad and then do what’s right.” (By way of contrast, Bud Fisher in a Mutt and Jeff strip from 1910 described a character as speaking “pure wop talk.” George McManus was similarly cavalier about using the slur “wop” in Bringing Up Father.)

African-Americans in Annie. For obvious historical reasons, Gray was much more gingerly about discussion anti-black bigotry but in a few strips he did make clear what his stance was. In 1927 Annie was, as so often, living as a tramp on the road, hungry and destitute. As a train car passes by, the African-American cook (drawn in a minstrel fashion) hands her a package of food. Annie and Gray make sure that the appropriate lesson is drawn: “A whole meal, Sandy! Whaddyuh think o’ that? An’ we never even asked him for anything. That just goes tot show you, Sandy, just ‘cause a bird isn’t our color is no sign he isn’t right – see?”

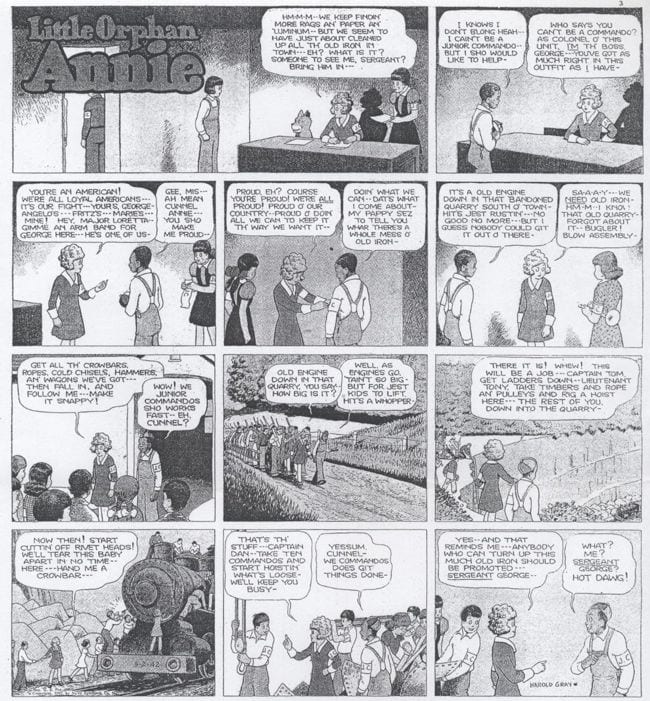

A Sunday page from 1942 takes up the race issue again in an even more interesting way. The war is going on, and the always active Annie has taken charge by organizing a group called the “Junior Commandos” which is trying to help the war effort by collecting goods for recycling. To appreciate the strip, it’s important to bear in mind that it was created at a point in time when the American army was still segregated (although the civil rights campaign for integration that would eventually succeed in 1948 was already starting).

As the Colonel of the Junior Commandos, Annie is approached by a black boy named George. Unlike earlier black characters in the strip, George is not drawn in a minstrel fashion but in the same style as the white characters. He speaks deferentially in a southern accent but his dialogue is also far less minstrel than the norm. They have the following conversation:

George: I knows I don’t belong heah – I can’t be a junior commando – but I sho would like to help.

Annie: Who says you can’t be a commando? As colonel o’ this unit, I’m th’ boss George --- You’ve got as much right in this outfit as I have. You’re an America! We’re all loyal Americas --- it’s our fight --- yours George. Angelo’s --- Fritz’s --- Marie’s --- mine! Hey, Major Loretta – gimme an arm band for George here – he’s one of us.”

George’s first act as a Junior Commando is to lead the troops to a great find, an old railway engine waiting to be salvaged. Annie immediately promotes George to the rank of sergeant. Given Gray’s penchant for political allegory it’s hard not to read the whole episode as a commentary urging the integration of the army.

The episode was certainly controversial in its time. Gray received many letters from African-American readers praising his portrayal of George and showing that blacks were an essential part of the war effort. The cartoonist also got an irate letter from a white editor in Mobile Tennessee upset that the strip showed a white girl consorting with a black boy.

I’ll talk more about this episode in an upcoming volume of the Little Orphan Annie series, but for now it might be worth asking why Gray, a man famous for being a right-wing Republican was also a critic of ethnic bigotry. In the early 20th century, most anti-racist activists belonged to the far left, being either anarchists, socialists, communists. But among mainstream political figures, the debate on racism was scrambled in very odd ways. Well into the 20th century, the Republicans remained the party of Lincoln, a legacy that meant much to Gray (his middle name was Lincoln, as was his father’s middle name). A Lincolnian commitment to equality of opportunity explains Gray’s progressive racial politics.