Comics fandom lost one of its best friends Sept. 12 when comics historian, biographer and lifelong fan Bill Schelly passed away at the age of 67 shortly after being diagnosed with bone cancer. Never less than supportive, gracious and respectful toward his fellow fans, Schelly was instrumental in coaxing a generation of comics readers out of their bat-caves and into a social network. His efforts as an amateur in the comics fan community earned him a San Diego Comic-Con International Inkpot Award for Fandom Services and led to a professional career as the widely praised biographer of Harvey Kurtzman, Joe Kubert, John Stanley, James Warren, Otto Binder and comedic silent film star Harry Langdon.

Schelly was born in Walla Walla, Washington, Nov. 2, 1951, but his family had moved to Pittsburgh when an encounter with Giant Superman Annual #1 in 1960 sparked an ecstatic love of comics that never left him. As with many fans, Schelly’s was initially a solitary obsession, but he soon bumped into a classmate in front of a drugstore spinner rack, and his new friend introduced him to comics fanzines. Fanzines like Rocket’s Blast Comicollector opened up a whole world of camaraderie.

In his 2001 autobiography, Sense of Wonder, Schelly wrote, “The rise of comic fandom was a genuine American grassroots movement. Entirely unplanned, it took hold in whatever fertile soil it could find. Fans emerged like so many wild mushrooms, popping up from sea to shining sea, from Peoria to Portland, from Nome to Norfolk.”

Schelly was one of them and, finding that he had an aptitude for drawing, he and his friend, Richard Shields, put together a Xeroxed fanzine called Super-Heroes Anonymous in 1964. It was the first of an off-and-on series of fanzines that, in later incarnations, went under various titles: Incognito, Fantasy Forum and Sense of Wonder, the last of which continued until 1972.

It wasn’t just comics that captivated Schelly, but especially superheroes. In an expanded 2018 edition of his autobiography, Schelly speculated that one reason for his interest may have been that, as a closeted youth, he identified with Superman’s burden of a secret identity. Like the superheroes whose adventures he followed, he felt alienated, different from the other boys in his classroom and neighborhood. “Should he tell his friends his secret,” he wrote. “What if, in the case of Peter Parker’s frail Aunt May, it would be too much of a shock? His enemies might use that knowledge to destroy him or his loved ones.”

This identity crisis was also one reason the discovery of a like-minded community of fans beyond his neighborhood was so important to him. As recounted in his autobiography, he came home one day bruised and bullied by rowdies at his local school to find an envelope containing fanzine Batmania #4 — with features about a redesigned Batmobile — waiting for him: “I opened up the pages, and soon I had completely forgotten my troubles. I was home again in Fandomland.”

In printing his own fanzines, Schelly felt he had become “a member of a brotherhood.” In the 1960s, which Schelly termed the “golden age of fandom,” fans were motivated essentially by a desire for inclusion and connection, and when he came out to his fellow fans, he found that he was no less welcome in the “brotherhood.”

Nevertheless, the first publication of his memoirs made no mention of his sexual orientation. It wasn’t until cartoonist Howard Cruse expressed disappointment in the book’s reticence on the subject, that Schelly decided to come out publicly in the expanded edition of the autobiography released in 2018.

In the late 1970s, Schelly drifted away from comics. But he was as much a cinema buff as a comics fan, and that interest did not abate. His comics-fanzine work had been fed by a voracious curiosity and meticulous capacity for research, but when he tapped into those elements to write a book, the subject was not comics but Harry Langdon, a comedic actor best known for a series of silents he had done with director Frank Capra. Despite threats from Langdon’s widow and lawyers, Harry Langdon: His Life and Films was completed and published by Scarecrow Press in 1982.

It was the first of several distinguished biographies and histories produced by Schelly over the years. But until he was able to retire in 2011, all were researched and written while Schelly worked at day jobs that ranged from drawing layouts for Boeing 767 designs to accounting for a fertilizer wholesaler to underwriting construction bonds for Surety Insurance Services and the Small Business Administration. For a time, in 1986, he even co-owned and co-operated a comics shop in Seattle called Super Comics and Collectables.

His intimacy with a fellow fan blossomed into a love affair but was defeated by geographical distance, and for the most part, long-term romantic relationships eluded him. But his friendship with Stephanie Seymour, a co-worker where he was employed as an accountant, set in motion events that led him to twice become a father. Seymour was in a relationship with Maureen (“Renie”) Jones. The couple wanted to have children and asked Schelly to help them conceive. In 1990, a son, Jamieson, was born to birth parents Schelly and Jones. A year later, Seymour gave birth to a daughter, Tara Jane, also fathered by Schelly. The kids were raised by Seymour and Jones, but Schelly played an ongoing role in their lives so that they had two moms and a dad. At age 14, Jamieson was diagnosed with testicular cancer, which he was able to beat, but in 2010 the disease returned fatally and, after a whirlwind bucket-list tour of Europe with his sister, girlfriend and cousin and a father-son trip to New York City, Schelly’s son died at the age of 20.

In 1991, having just become a father, Schelly found his interest in comics re-igniting and he joined Capa-Alpha, an Amateur Press Alliance, in which members contribute to a joint fanzine. A visit to the 1994 San Diego Comic-Con inspired Schelly to conceive a book that would bring to light the untold history of comics fandom. Publishers didn’t get it, though, and none would greenlight the project. Schelly’s frustration led to what he described in his autobiography as his mad-as-hell-and-not-going-to-take-it-anymore moment: “I was sick of being told ‘no’ in my life by the powers that be. No, you can’t have a career in the arts. No, you can’t love the person you want. No, you can’t have children. No, your book isn’t worth publishing.”

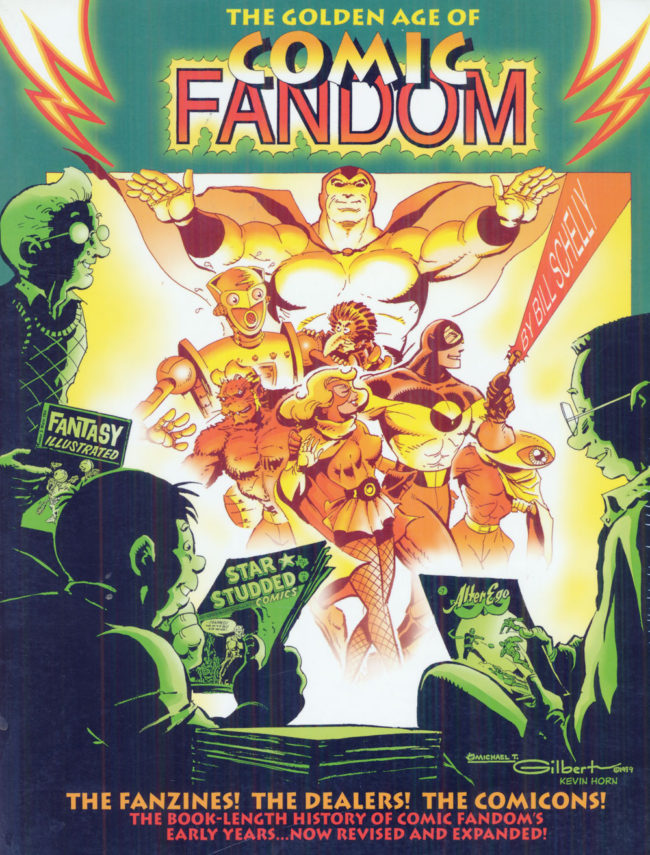

As always, unwilling to take no for an answer, Schelly formed Hamster Press and published The Golden Age of Comic Fandom himself in 1995. It turned out to be a strong seller and was nominated for an Eisner award and twice expanded and reprinted. It was followed by a 1997 collection of fanzine-published comic art called Fandom’s Finest Comics, also published by Hamster Press. That same year, Schelly took it a step further and organized a Fandom Reunion event at the Chicago Comic Con that brought together many fanzine publishers and contributors for the first time in the flesh.

Hamster Press published nine books between 1995 and 2004 and managed to do so without losing money, a major feat for a small press. Many of them covered fan culture, but one of its more ambitious projects was Schelly’s Words of Wonder: The Life and Times of Otto Binder, the definitive biography of the seminal comics and science-fiction writer, published in 2003 and re-issued in 2016 as Otto Binder: The Life and Work of a Comic Book and Science Fiction Visionary.

Moving beyond self-publishing, Schelly’s first book for Fantagraphics was Man of Rock: A Biography of Joe Kubert. Overcoming Kubert’s initial resistance, Schelly managed to deliver a thoroughly researched book that was followed by two Fantagraphics collections of Kubert’s work curated by Schelly: The Art of Joe Kubert (2011) and Weird Horrors and Daring Adventures (2012).

Schelly’s 2013 book for TwoMorrows Publishing, American Comic Book Chronicles: The 1950s was nominated for a 2014 Harvey Kurtzman Award.

But Schelly’s next book for Fantagraphics topped everything that had come before it: Harvey Kurtzman: The Man Who Created Mad and Revolutionized Humor in America. Published in 2015, the 624-page book won rave reviews and the Eisner Award for Best Comics-Related Book. Steven Heller, writing for The Atlantic, described the book as “exhaustively researched.” D. Douglas Fratz of The New York Review of Science Fiction counted Schelly “among the finest writers of biographies in the comics field,” adding, “His signature ability is to illuminate the life as well as the work of his subjects, which he does extremely well in both the Kurtzman and Binder biographies.”

Schelly went on to write similarly well-received books on John Stanley (Giving Life to Little Lulu, Fantagraphics, 2017 and James Warren (Empire of Monsters: The Man Behind Creepy, Vampirella and Famous Monsters, Fantagraphics, 2019).

But for members of the comics fan community, Schelly’s greatest triumph may have been the 2011 Comics Fandom 50th Anniversary Reunion at the San Diego Comic-Con International. The event brought together some 150 of his fanzine brethren. Since Schelly was adamant that there be no microphones, speakers, platforms or interruptions — essentially no program — the Reunion consisted of nonstop animated conversation between friends who rarely saw one another. Schelly was given the Inkpot Award for Fandom Services at the same con that year.

In the last couple of years, the flow of books from Schelly was only increasing with a collection of essays (The Bill Schelly Reader) and a never-before-published coming-of-age novel (Come With Me) from Pulp Hero Press and audiobook editions of his earlier books from Penguin Random House. One of the books to receive the audiobook treatment was the expanded edition of his autobiography, Sense of Wonder, published in print in 2018. The memoirs gave critics an opportunity to comment not only on the book, but on the significance of a life lived in comics.

Batman movie producer Michael Uslan wrote, “Bill Schelly was one of those integral people responsible for nurturing and growing comic book fandom until the rest of the planet finally began to join us, bringing comic books and superheroes from the subversive to the mainstream. For that, the entire world today owes him its thanks for a job well done!”

Game of Thrones author and erstwhile fellow toiler in the fanzine trenches, George R.R. Martin wrote, “Reading Bill Schelly's fond, funny and nostalgic memoir was like going home again.”

Film critic Leonard Maltin wrote, “The author is living proof that a lifelong passion can pay off in countless ways, both personal and professional.”

At the end of Sense of Wonder, Schelly’s voice rings with the satisfaction of a man who has reached the top of an enormous mountain and defeated the loneliness that had clung to his early years. He had been welcomed into two families, the Seymours and the Joneses, and had fathered two children, of whom he was extremely proud. He had brought together a dispersed family of fans at the San Diego reunion. He had personally been reunited with his romantic love after a long separation. He had won an Eisner Award.

“Mine has truly been a life in comic fandom,” he wrote, “since the years when I foolishly strayed have now faded into insignificance.”

In the final weeks, Schelly had sounded confident that his condition could be successfully treated. Cause of death was blood clotting in the lungs during chemotherapy. Maureen Jones, the birth mother of Schelly’s late son, was by his side much of the time at the hospital, and his daughter Tara flew in to be with him.