Fantagraphics has just released John Stanley: Giving Life to Little Lulu by Bill Schelly. We asked cartoonist and historian Mark Newgarden to interview Schelly about the book, the artist, and his own history.

Fantagraphics has just released John Stanley: Giving Life to Little Lulu by Bill Schelly. We asked cartoonist and historian Mark Newgarden to interview Schelly about the book, the artist, and his own history.

Your last project was a thorough, painstakingly researched biography of Harvey Kurtzman, a fairly high-profile pop cultural figure who, as you describe in the book’s subtitle “revolutionized humor in America.” After that, why John Stanley?

The Kurtzman book was a dream project, but it was long and incredibly involved. Wrangling that much information was almost beyond me. I knew a biography of John Stanley would be much shorter, because his career in comic books and publishing wasn’t as varied. The people who worked with him were already dead. There were many fewer sources of information, so it seemed a lot more manageable. At the same time, I felt John Stanley’s work was worthy of committing a couple of years of my life to writing about it, because I rank his best work right up there with people like Kurtzman, Eisner, Barks, Kirby and Crumb. Plus, I was enthused that Gary Groth agreed that it should be a big, full-color coffee table book.

Who was John Stanley? Can you describe some of the inherent difficulties you encountered in researching the life and career of this significant, yet (nearly) anonymous mid-20th century multi-mass-media worker?

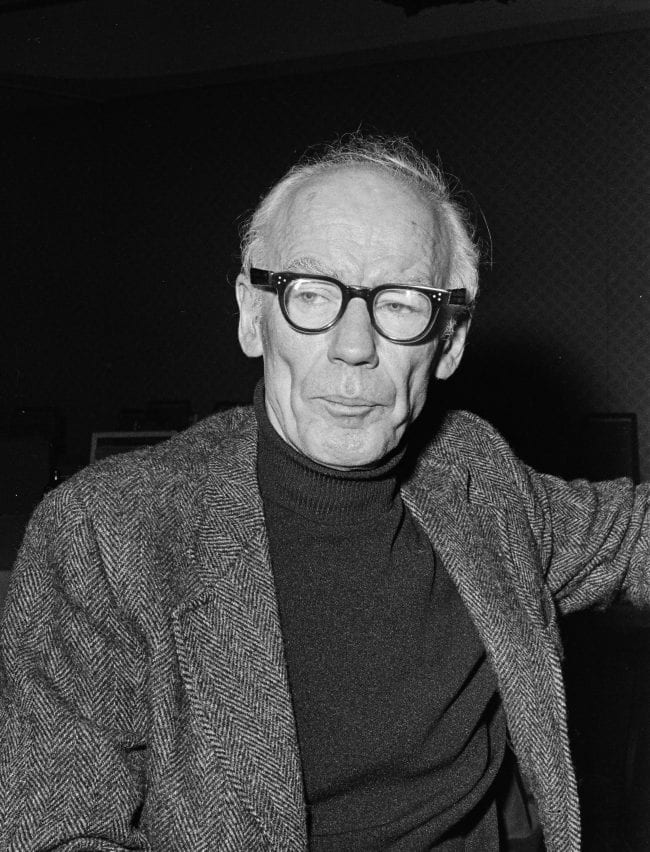

John Stanley was born in 1914, a son of Irish immigrants who was brought up in the Bronx, and lived in New York City environs all his life. He died in 1993. He only gave three interviews in his life, two of them being question-and-answer sessions on panels at NewCon 1976, the only comicon he ever attended. He shunned the limelight, largely because of his natural reticence plus an extremely self-deprecating attitude about his work, and a career that ended badly. In contrast, Harvey Kurtzman must have given forty or fifty interviews, many of them extensive.

By 2014, when I starting doing my research, virtually all his colleagues and friends, not to mention his birth family and wife, had passed away. Only a few had been interviewed about him. His son Jim Stanley, the chief caretaker of his father’s legacy, was born in 1962 and he was still a child when his father quit comics in 1970. So putting John’s story together, and tracing how one event led to another, was a challenge. I’m happy with the way it turned out. I was able to unearth a lot of previously unknown stuff.

What were some of your discoveries?

Jim sent me a lot of unseen photos from his father’s youth, as well as sketches and his attempts at a newspaper comic strip. He filled in a lot of information about the last 25 years of his father’s life, and provided some unpublished art from that period. Plus, he put me in touch with his older cousin, Barbara Stanley Steggles, who remembered a lot about the Stanley family and her Uncle John. She also contributed photos and artwork. Between the two of them, I was able to construct a portrait of the cartoonist, his early life, and his personal struggles with alcohol and depression.

A major find was a series of gorgeous 35 mm photographs taken at the 1976 NewCon by E. B. Boatner. One of the best was used on the book’s cover. Even at 62 years old, he was still a handsome guy.

Stanley was reputedly also a New Yorker cartoon gagman for a fair stretch of his Dell comics career (although he was only once allowed to take one to finish himself.) I found this a particularly tantalizing part of his story, given we know so little about who actually “wrote” so many iconic New Yorker cartoons of this era. How far were you able to dig down that particular rabbit hole?

Once I realized that Stanley had a full page cartoon continuity in the March 15, 1947 issue of The New Yorker, I figured he had to have done more. This was bolstered by a sheaf of New Yorker-style cartoons that existed in sketch form. Interviews with Dan Noonan and Morris Gollub, two of Stanley’s colleagues at Western Printing, confirmed that Stanley was very successful in selling gag ideas to the magazine. But, as Noonan said, New Yorker art editor Jim Geraghty would assign them to other cartoonists (as was often their custom) to finish.

Apparently a number were rendered by Whitney Darrow, one of the most celebrated cartoonists at the magazine. If so, how could we identify Stanley’s? John Stanley expert Frank M. Young scoured every issue of the magazine from 1946 to 1955 to see if any of the extant sketches appeared in final form, or if there were any others signed by Stanley. No dice. We were never able to figure out how to dig deeper. Unfortunately, Jim Stanley didn’t have any pay vouchers among his father’s papers. Maybe somewhere in the bowels of the magazine’s archives, answers could be found among the thousands of gag cartoon submissions.

What distinguishes Stanley from the hundreds of other comic book makers of his era, many of whom not only shared his lack of pretense, but perhaps also a casual disregard for the medium they toiled in?

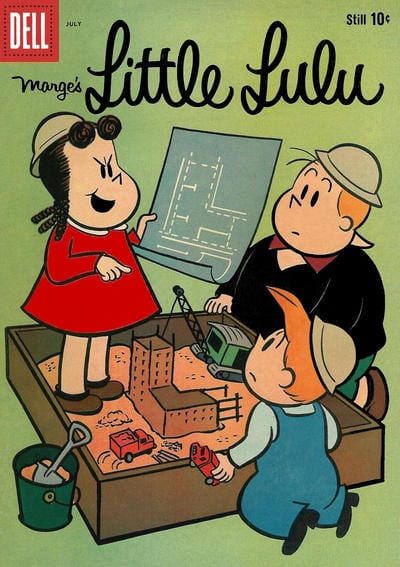

What distinguishes Stanley is the exceptionally high quality of his work as a cartoonist and storyteller. His stories tell the truth about children in some of the funniest stories to ever appear in comic books. He didn’t aspire to draw comic books, but, when he fell into it during World War II, it proved to be his true calling. From the moment he walked into the Western Publishing offices in 1942, his work was very good, well up to professional standards. By the time he’d spent a couple of years writing and drawing such features as Tom and Jerry, Andy Panda and Woody Woodpecker, he had earned a reputation in the office as one of the top freelancers working for Western (Dell comics), right up there with Walt Kelly on Pogo and Carl Barks on Donald Duck. That’s why he was given the plum assignment of adapting Marjorie Buell’s character Little Lulu for Western, after she had appeared for 10 years in a wordless gag panel in the Saturday Evening Post.

Can you give us some background on Western Publications in this era? What was the editorial culture that enabled an ex-Disney merch artist like John Stanley to walk in that door and be given a chance to take on so much creative freedom fairly quickly?

A key factor is that Stanley was 4-F, due to a collapsed lung and a history of childhood tuberculosis, so he was available when so many cartoonists had been swept into the US military in 1941 and 1942. Also in his favor was a portfolio with examples of his work on Disney characters, which he had been drawing for a licensee for several years. Therefore, it’s understandable that Western’s editor Oskar Lebeck figured it was worth giving him a try-out. Similarly, letting John try his hand at scripting wasn’t that big a gamble. Of course, other editors might not have reacted favorably when Stanley asked to draw an episode from his own script, but Lebeck was good at recognizing talent and potential. As it turned out, he was right to intuit that Stanley would come through.

What made Little Lulu exceptional? What distinguished this series from Stanley’s other comic book assignments as well as other contemporary comic books aimed at the same demographic?

Stanley was a true auteur. He wrote, drew and lettered the first three Little Lulu comic books (Dell Four Color #74, 97 and 110) all by himself. When these proved successful, and Lulu got her series after several more try-out issues, Lebeck let him work essentially unsupervised for the remainder of his tenure as editor. While others were brought in to do the interior art from his layouts, mainly Irving Tripp, Stanley did the finished cover art on Marge’s Little Lulu all through the 1950s. He gave Tripp detailed layouts for the Lulu stories, which Tripp followed faithfully. So it’s essentially one person’s idiosyncratic vision. In all, he wrote more than 6,000 Lulu and Tubby pages.

While it’s true that Marge created Lulu Moppet and Tubby Thompkins, it was John Stanley who gave Lulu much of the personality we associate with her, and who developed Tubby into one of the most complex characters to appear in any comic book. Tubby’s infuriating narcissism, sexism, arrogance, and insensitivity make him a perfect foil. He’d be a monster if he wasn’t essentially likable. Stanley created the entire cast of supporting characters such as Alvin, the Boy’s Club, and Witch Hazel, and stories that captured the way kids really were, and are. Young readers experienced a “shock of recognition” when they read those comics. I suspect a lot of older readers liked them, too. As a result, Marge’s Little Lulu and Marge’s Tubby were some of the bestselling comics of the 1950s, with print runs topping 1,000,000 copies per issue.

His non-Lulu work was generally clever and a cut above average, and his self-created series in the 1960s, Thirteen (Going on Eighteen) and Melvin Monster, have moments of brilliance. But somehow, nothing he did clicked like Lulu.

Can you tell us a little bit about Stanley’s creative process and if you think it may have contributed to the “real life” flavor of his narratives? It really seems to defy the typical “how-tos” of mass-market storytelling.

Stanley worked in a stream-of-consciousness way. He would come up with a premise, and just work along from sequence to sequence, somehow knowing that the story would reach a logical conclusion. His stories don’t seem contrived. They unfold the way things do in real life, where one things leads to the next. He said he wrote that way because he didn’t have time to plan. There were times when he got stuck and had to set a partly-done story aside, but this seems to have happened rarely. He developed a cast of specific personalities, and knew how to put them together to create humorous situations, and then raise the stakes as the story progressed. He could do this without planning even when he knew a story had to fit a certain page count. Yet most of the endings are extremely satisfying, and often quite breathtaking. We have to finally accept that it’s a bit of a mystery. It’s just something he could do.

In what respects has Stanley’s Little Lulu aged well for a 21st century kid audience (and in what respects hasn’t it?)

The feminist message in Little Lulu is as relevant today as it was in the 1950s. Lulu wanted nothing more than to show that a girl can do anything a boy can do, and that girls are often smarter than boys. This theme, explicitly stated, runs through a large percentage of the stories. But even more than that, there’s a universality to the stories because children—their striving, their mistakes, their efforts to be accepted by others, the way they process information—never really change.

Modern audiences will notice the lack of diversity, and the way the characters are clothed. Plus, references to children being given “a good spanking” will bother some people. At the time, spanking was a form of discipline accepted by parents and children alike. (For the record, Jim Stanley told me that he and his sister were never spanked as children.)

From 2005 to 2011, Dark Horse published a series of trade paperback books reprinting Little Lulu stories by Stanley, about 30 books in all. I’ve heard of plenty of parents buying them for their children, and the books being very well thumbed. They’re just fun to read.

What’s next for Bill Schelly?

My next book, which will be published by North Atlantic Books in May of 2018, is my expanded memoir Sense of Wonder, My Life in Comic Fandom – The Whole Story. The original version, published in 2001, told about my adventures as a fanzine publisher in the 1960s and 1970s, and left off in 1974, when I moved to Seattle to find fame and fortune. Well, I didn’t find either of those, but I do know what happened in the ensuing years, including being a part owner in a quixotic comics retail store, struggling to get a book published, and finally realizing that writing about the history of comics was my creative mission in life. It all leads up to winning the Eisner Award for Harvey Kurtzman, The Man Who Created Mad and Revolutionized Humor in America in 2016. The book includes the original text, and an all-new “book 2” of equal length.

One key difference is that I didn’t come out as gay in the original book. Comics with muscular superheroes clad in spandex were received a little differently by a gay boy than a straight boy. A “secret identity” had special meaning for me…. And so on. I don’t think anyone has written a book describing a comics fan on similar journey. It’s a journey of hope and striving by someone who was a late bloomer – a deeper, more honest memoir than my first attempt.