When Steve Ditko died in 2018, his family had difficulty opening his office door because it was blocked by piles of unopened correspondence.

Fan letters and packages had piled up in an accidental monument to the enigmatic creator and co-creator of Spider-Man, Doctor Strange, the Creeper and other beloved characters.

Almost three years after his death, more analysis and new information about Ditko—some of it from Ditko’s own letters—is coming to light, most recently in two new books, Mysterious Travelers: Steve Ditko and the Search for a New Liberal Identity by Zack Kruse and Ditko Shrugged: The Uncompromising Life of the Artist Behind Spider-Man by David Currie.

The correspondence Currie published, with the blessing of the Ditko family, is particularly illuminating of his life, personality and worldview, making it a strong companion piece to Blake Bell’s 2008 book Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko. Currie’s letters with Ditko open up a biography that had previously been defined by Ditko’s own rejection of the mainstream media spotlight, his independently published essays and his association with Ayn Rand’s Objectivism philosophy.

In a letter that could have been dated last month, let alone 2012, Ditko told Currie that “Even today, too many now don’t care about the difficult lessons learned in the past...A big problem is that too much is done by too many to protect, excuse the wrong, bad, even the evil.”

In another exchange, Ditko takes aim at his editor and Spider-Man co-creator, Stan Lee.

“Stan promoting Marvel titles worked more [as Stan] promoting himself. He took advantage of an opportunity and it keeps paying off,” writes Ditko, who cast himself as the opposite of Lee. “Wanting, needing some public recognition status, being a public celebrity, a false ego-building, pandering to others, fans, crowds with interviews, etc., is self-defeating.”

Currie told me that the dozens of letters he exchanged with Ditko offered “plentiful insights” and most ran “contrary to some perceptions of him.”

“He didn’t retreat Salinger-like from the world but had a preferred method of communication that was becoming increasingly outdated in modern times but nonetheless important to him, and he saw no need to change,” Currie wrote. “I would imagine, and hope, that within the reams of correspondence he wrote over his lifetime, there are many more insights yet to be revealed.”

Such a collection would be difficult to make encyclopedic, since Ditko wrote so much and didn’t keep copies of his letters.

“You have to understand that he probably wrote many hundreds of letters every year, amounting to many thousands over the decades. Where would he store them all?” said Ditko’s nephew, Mark S. Ditko. “I know one person that exchanged around 1,500 letters back and forth with him. That’s only one person.”

That’s a lot of correspondence. For context, Ernest Hemingway wrote an estimated 6,000 letters in his lifetime, and those that survived are being published by Cambridge University Press in a projected 17 doorstop-size volumes. Having written two books about Hemingway myself and contributed letters I found to the project, I’m familiar with the genre of publishing literary letters. And just using back-of-the-envelope math, Ditko far outpaces Hemingway.

Even today, Ditko’s letters regularly pop up on eBay and other auction sites, and since 2018, publisher Craig Yoe has curated a Facebook group of letters that Ditko sent to fans. There was even an unauthorized book, Regards, Ditko: An Exploration into the Mind of Steve Ditko, published by Jaison Chahwala. That 2019 collection featured Ditko’s often lengthy letters to Chahwala, largely dealing with Objectivist principles. (It also features at least one insight into the Lee / Ditko dynamic. When Chahwala shows Lee some of his correspondence with Ditko, Lee tells him with a laugh, “You tell him I said hello, and you tell him that he drove me nuts!”)

Together, these sources shed light on Ditko’s prodigious letter-writing practice.

“If you wrote to him, he would reply. And it didn’t matter if you were 10 years old or 70,” says Mark Ditko. “He was always available through written correspondence, and it seems that writing letters eventually became one of his preferred methods of corresponding with his admirers, friends, family and business associates.”

Given some of Ditko’s responses—“I can’t answer questions about someone’s curiosity about me or what I did,” he told one fan—it makes you wonder why Ditko responded at all. It seemed like a compulsion, or perhaps just good manners, that Ditko replied to people who took the trouble to write him, even when that response could be brusque.

He told another fan: “The questions you asked are not important to my life or well-being. My focus is on ‘What’s next?’ ”

Yet, people wrote him, myself among them.

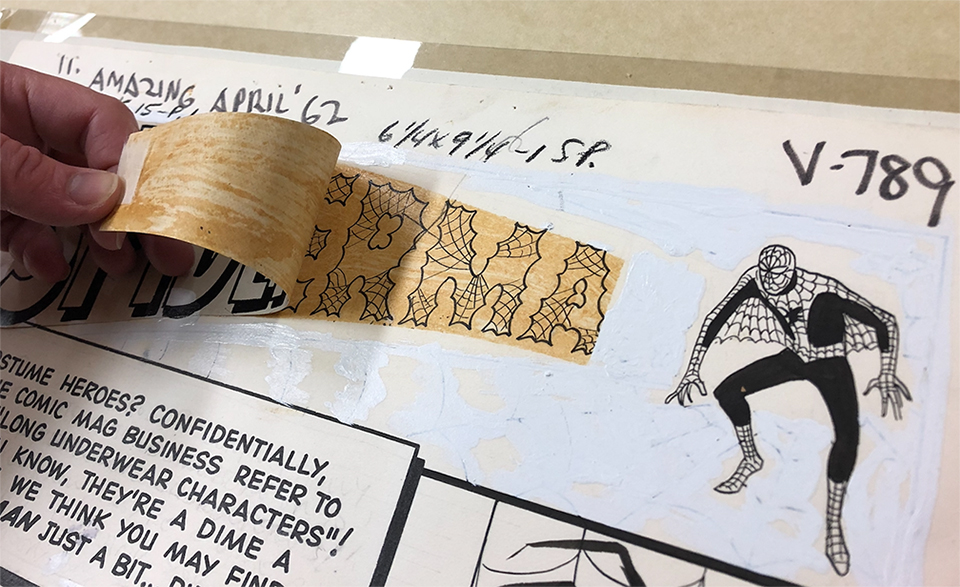

In 2008, when his pages for Amazing Fantasy #15—including the first Spider-Man story—were donated to the Library of Congress, I reached him by phone at his office. After I introduced myself and told him about the story I was writing for the Chicago Tribune, Ditko told me that he “couldn’t care less” about his artwork’s final destination in Washington D.C.

“Is there anything else you want to tell me?” Ditko asked me, before we said our good-byes and hung up.

When I sent Ditko a copy of the story, he wrote back thanking me. I followed up the next year, knowing I’d be in New York on other business, and I asked if he’d be willing to participate in a series of stories I was doing for Wizard magazine about artists and their studios. I’d published stories about Todd McFarlane’s and Phil Jimenez’s studios, and I thought there’d be little harm in asking Ditko. I was wrong.

“Let me get this right,” Ditko wrote me in October of 2009, “...you want to publicly expose everything that is inside my studio, that is, expose my private property and my right to privacy. What do I think? I know, NO.”

But what did he write to other people?

“The length of his exchange was really dependent on the contents of the letter. If there was something that warranted a lengthy exchange, then he had nothing holding him back from writing an appropriately lengthy response,” Mark Ditko says. “He didn’t generally write long letters to ‘fans.’ He wrote to exchange mutually valuable and relevant information with his friends, family and associates.”

What he wrote about depended on what you wrote him, his nephew says.

“And in that respect he was no different than any other reasonable person,” Mark Ditko says. “He’s worked on hundreds of comics over many decades and when the 1,237th person asks him ‘Why did you leave Spider-Man?’...You’ll likely get a polite ‘...that was 40 years ago, I’m working on other projects now.’ And that would be that. But if you asked for advice on your drawing skills, or for his thoughts on some current event, or something ‘real,’ he would respond in kind.”

There’s been talk of a book collecting of Ditko’s letters, though no publishing date has been announced yet. Mark Ditko describes the project as “In progress and on the table for further discussion.”

With a new biography of Stan Lee out this year, Abraham Reisman’s True Believer—and a high profile rebuttal by former Marvel editor Roy Thomas in the Hollywood Reporter—the demand for more work about Marvel’s early days increases, as does the size of Marvel’s entertainment empire under Disney.

It seems that there is plenty left to explore.

Kruse’s new book, Mysterious Travelers: Steve Ditko and the Search for a New Liberal Identity, offers a closer textual reading of Ditko’s work and themes. In part, the book re-examines Ditko’s association to Objectivism, which Kruse defines as “Ayn Rand’s philosophy in which she identifies capitalism as a moral, political and ethical ideal.”

“He’s his own mind, he’s his own independent thinker,” says Kruse, an assistant professor at Michigan State University. “He’s beholden to no mind...and tethering him to Rand or Libertarianism or the Right ignores the complexities of his work.”

In many ways, Kruse argues, tying Ditko to Rand limits him.

“Ditko was interested in stories of redemption,” Kruse says. “His sense of justice doesn’t come from Objectivism, it comes from his own lived sense of the world.”

Like Currie, Kruse also exchanged correspondence with Ditko, and even met him at his office in Times Square, which Kruse writes about in the new book. Stories like these, as more letters and biographical details emerge, are fertile ground for future scholars.

“We’re at the beginning of Ditko scholarship,” Kruse says. “There’s something of a cottage industry in re-reading Steve Ditko. I think that we’re going to get a much closer glimpse into his life and work that will make us rethink a lot of assumptions we had.”

Robert K. Elder is the author of 15 books, including Hemingway in Comics, out now from Kent State University Press. For more information about Elder, visit robertkelder.com.