I had been under the impression that Comix India, inaugurated in 2010, was the first amateur comics magazine in India. It might have been the first with significant heft and geographical reach. Chronologically, however, there is at least one precedent.

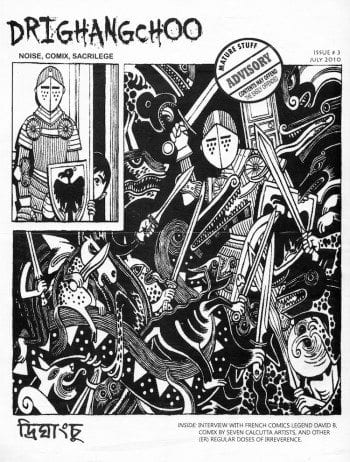

Out of Kolkata’s Jadavpur University in 2009 came Drighangchoo. It only lasted three issues. It is a pamphlet affair in black and white. The first issue is half prose, but by no. 2 Drighangchoo is a robust comics magazine. It is printed cheaply but the artwork can be as good as what one finds in the luxurious mini-comics from Manta Ray in Bangalore. And dealing as some Drighangchoo comics do with harder social issues, it is generally a meatier magazine than its more polished peers. It definitely feels like something produced on a university campus, due to its jocular but palpably self-conscious editorial commentary, peppered with baroque self-deprecations and mocking academy-ese. But the evident earnestness of the project and the increasing quality of the contents and production from issue to issue suggest that, had it lived a bit longer, Drighangchoo might have become a standard-bearer in amateur comics publishing in India, or at least in Bengal.

Getting ahold of the issues was a bit of work, and not just for me. After a series of forwarded emails, I finally was put in touch with Deeptanil Ray, an about-to-graduate PhD student at Jadavpur University and one of Drighangchoo’s five founders. “It's been two years since the last issue was published and it's really nice to hear people still interested in it. The magazine is no longer functional but I do have one or two extra copies of the three issues we published which I can mail you if you let me know of your postal address.”

He might have regretted this offer later. The first package he sent to my apartment in Mumbai was eaten by India Post. The arrival of the replacement shipment was secured only after Deeptanil stood in queue for part of a day to get tracking and signature confirmation. And this was just the beginning of his labors. I asked him to answer some questions about Drighangchoo over email, to which he responded most generously with the series of mini-articles below on Bengali comics and cultural history, as well as on the magazine itself. The byline on this article should probably be his.

Before moving on to the interview, a quick note that Drighangchoo is not the only comics-related enterprise to come out of Jadavpur University. Abhijit Gupta, who teaches literature at the university, is directing The Comic Book Project. Its aim, part of a larger archiving endeavor conducted by The School of Cultural Texts and Records at Jadavpur, is to collect and digitize comic strips from vernacular (meaning non-English) Indian periodicals since the 1950s. In an interview with the Sunday Guardian, Gupta explained, “In the case of comic books, there is a wealth of material in Bengali, Malayalam, Hindi, et cetera, which is in the danger of being lost since they came out in magazines and were often not collected later. There were also small, local comic book publishers who published on a very small scale, often stopping publication after 3-4 titles. Then there was the use of the comic-book form in advertising. In the case of Indian comic books, Amar Chitra Katha and Indrajal comics have been extensively digitized but not the other stuff.” If the preparatory blog is any indication, this promises to be a stupendous resource. Once fully operational, reportedly about ten percent of the material will be available for free online, while the entire physical archive will be open-access at Jadavpur University.

From the following interview with Deeptanil, conducted in November 2013, one gets the sense that this deeper history of Indian comics is part of the genetic makeup of amateur cartooning in Bengal, much more than in the case of the manga-inspired and online discussion board-supported Comix India. Or maybe only Deeptanil has a special obsession with the past – I cannot parse the style of Drighangchoo’s comics to say myself. Having spent no time on the east side of the subcontinent, and very little with Bengali art and literature, this interview was pure education to me.

Embarrassingly the only reference I could identify with has nothing to do with comics. It comes toward the beginning, where Deeptanil is talking about crows in Kolkata, which are also aplenty in Mumbai. I thought maybe it was just me, but I have been shit on by birds more times during a year living in Mumbai than otherwise in the previous thirty-six years of my life. Not just more times, but many more times. I can count three splats on my shoulder in the past week alone, and probably two dozen over the year. This not including a plop in my beer in Goa – an impressive bullseye through the narrow mouth of a Kingfisher bottle. Who knows how many occasions I didn’t notice because of my maginificent full head of hair.

What does the magazine's title mean and how do you pronounce it?

Drighangchoo, or Dree-Ghang-Choo as we spell it in Bengali: “Dree” as in Adrian; “Gha” as in Ghana; “Ng” as in Gang; and “Choo” as in Fu Manchu. The word has its origins in a short story of the same name by Sukumar Ray, a popular author, poet, and dramatist in Bengal from the early twentieth century. He was also one of the early experimenters in nonsense verse, a children’s writer, an expert in half-tone printing (his father was one of the inventors of the process), a brilliant illustrator and cartoonist, and a sharp-witted political satirist. In “Drighangchoo,” Ray tells the story of a mystery raven that arrives one day at a king’s court, and goes “Caw!” The king calls in all the pundits, who fail to explain the metaphysical significance of bird’s monosyllabic caw. Then, a man arrives and identifies the raven as a strange creature of metamorphosis: he calls it Drighangchoo. He teaches the king a nonsense poem to recite to Drighangchoo, the next time he sees it, and promises that a wonderful thing will happen. At the end of the story, the king spends the day chasing crows and ravens. But Drighanchoo is never heard of again, nor do we know of its wonders. Ray’s work is very difficult to translate, but you can find a rather literal and unimaginative translation here.

Since Sukumar Ray, Drighanchoo has come to mean many things in the Bengali cultural imagination: a creature of metamorphosis, a mystery bird, nonsense, trickstery and fun in all seriousness, a Borhesian object of infinite possibilities. Since we were planning to have fun with a comics magazine for “mature readers,” primarily meant to cure readers in this part of the world thinking of the medium solely as a form of juvenile recreation (like all small press publications, we had begun with grand desires, you see), we thought the name would suit our mag. The naming also had something to do with the location of our publication headquarters: a corvus-infested open-air canteen in Jadavpur University, where there are still a lot of dive-bombers watching you from the trees when you’re reading Kafka, ready to snatch your lunch, and white manna from the heavens occasionally drops on your head and coffee via some contemplative crow’s intestines.

How did the magazine come about?

The idea took shape sometime in early 2009. Osamu Tezuka had arrived at the city’s bookshops, and you could buy a hardback copy of Art Spiegelman’s Breakdowns without raising too many eyebrows in Kolkata. For Robert Crumb, Thomas Ott, Chester Brown, Jason, Eisner, and Tezuka: there was always a library on the internet called Gigapedia. Other things had happened too: corporate globalization in India, violent land acquisitions, the brutal killing of peasants at Nandigram by a left-wing state government, the empty slogan mongering of most pro-people resistance movements, urban decadence, the enormous loss of faith in the Left. Drighangchoo appeared with these things going on the backdrop and in our minds. Sarbajit Sen’s wordless comics in the first issue – about a villager chased off his land for an upside down world devoured by giant cranes and other monsters accompanying “industrial progress,” then chased off again and again till he reaches the end of the big upside down world and finds himself together with the last of the human survivors chased off a melting South Pole – is symptomatic of this context. As are our editorials.

I was in the first year of my PhD fellowship, and spent most of the time reading comics, downloading stuff from the web, playing the occasional librarian at Gigapedia, thinking. Then, I was also illustrating a book-length comics written by a British-Indian author (the project fell through half-way), and working on my comics in bits and pieces (it didn’t materialize), when Tintin-da (Dr. Abhijit Gupta, one of my teachers at the English department, a good friend, and a die-hard comics enthusiast) first suggested the need for a comics magazine in Kolkata. In April 2009, during the usual angst-laden PhD student blabber at the canteens, me and Debapriya Basu (a fellow PhD student, a friend, and a poet) began discussing the mag in all seriousness. We were to have a magazine on “noise, comix, and sacrilege”, with the greater part of it devoted to comics and sequential graphic art.

The mag was to be bilingual: printing works in English, and also encouraging takes in the Bengali language in which, as far as I know, no comics has been published so far that go beyond children’s adventures and cartoons, detective and spy stories, and other run-of-the-mill stock (except, of course, the singular attempts by Prasad Ray, who published under the name of Mayukh Choudhury during the 1960s and 1970s). Anyway, Debapriya brought two of her research-scholar friends, Shubham Roy Choudhury and Spandana Bhowmik, and I roped in Tintin-da and Anindya-da (Anindya Sengupta, an assistant professor at the Film Studies department, a friend, and an author), also Soumik Datta (a postgraduate and student activist; a folk-music archivist now). In two days, I had drawn a cover for the mag and a short two page strip called “Porijayi” in Bengali, about a construction worker from the villages who loses his way in the city, decides to jump from an unfinished skyscraper, and grows wings to fly out of the city, all the birds leaving with him.

With the editorial team in place, and everyone excited, there was only one practical problem to be solved. Apart from me, who used to doodle a lot in the classrooms and whose friends called an “artist,” none of the other editors wanted to try their hands at comics. We were in serious need for contributing artists. I remembered Pinaki De then (a graphic artist, designer, and a departmental senior who taught at a district college), and called him ecstatically over the phone. We got another editor in him, right away, super-excited about the project. In a week, we had put up posters throughout the university, and went asking about in the city for comics artists. I had met Sarbajit Sen (a comics artist, designer, and a documentary filmmaker) earlier, but this time I met Sarbajit-da and talked for hours about comics, finally finding the courage to ask him about contributing a piece. Anindya-da (who became the edit writer for all our issues) wrote us a kind of manifesto in the form of a pseudo-academic seminar paper from two hundred years in the future, which later became the first issue editorial. And the magazine was on.

Why two languages, Bengali and English? It seems to me in the rest of India there is a pretty strong divide between Anglophone culture and the regional Indian-language culture. Why is Bengal the exception?

It is mostly a matter of state policy and bureaucratic judgment in identifying one language as “national” and others as “regional.” Societies and individuals often do not live to these definitions. We (and by that, I mean, most of us who were children in West Bengal in the 1980s and early 1990s) had grown up reading books in Bengali and English, and also lots of Soviet and Chinese children’s books that were available both in English and Bengali. Often, we had two copies of the same book in two different languages: as were our collections of second-hand Indrajal Comics in Bengali and English. And that was a matter of additional pride. I have had professors who know Greek and Latin, teach English, and write excellent Bengali prose, often translating books from one language to another. And I’ve got some friends who switch between two to four languages unconsciously while speaking, and in fact a friend who speaks eleven languages fluently and reads eight with ease. Multilingualism is a common feature throughout India, but I think I’m digressing.

We never discussed this at length, but bilingual was the natural choice for our mag. There are more than a thousand languages in the Indian sub-continent, and every language brings with it its own set of sociocultural stereotypes. Perhaps it was working in our minds that opting for a single language of expression would have us stick to certain stereotypical notions pertaining to the language sphere within which we chose to operate. If it were only in English, we would have immediately distanced ourselves from many who understand English (and not always, incorrectly) as the language of the Indian power elite. If only in Bengali, we would have been typified as one of those Bengali little magazines that choose to bask in the glories of their linguistic ghettos. Probably, we wanted to avoid this typification and concentrate on what we considered our principal task: comics and visual culture.

Ah, the divide exists here as well. Although most Bengali-speaking people hate to admit to it, West Bengal (for there’s always an unreachable East that exists across the border with Bangladesh) is not an exception in this regard. In fact, the colonial hangover looms large over here: perhaps larger than it exists across the rest of India, and English is the primary language of power. But there’s perhaps a slight difference, which has its roots in the strong sentiments occasioned by the Bengal Partition and in the anti-colonial struggles of the Bengali-speaking people who stood for their language and culture in an atmosphere of extreme Anglophilia. There were many among our colonial-era Bengali writers, for example, Tagore, who moved with equal ease across Bengali and English, and saw the survival of Bengali culture in internationalism (not the Bolshevik kind) and cultural exchange, which was kind of opposed to the narrow-minded nationalism of the political class.

The strong undercurrent of left-wing political movement in this state, since the 1940s, also had had its impact in bridging the cultural divide, somewhat. Then, there was the Naxalbari movement, and the liberation struggle in Bangladesh, coinciding with the Paris 68 student movement and anti-Vietnam war protests around the world, which resulted in a different upsurge of internationalist cultural sentiments. Pete Seeger and Dylan; Allen Ginsberg and the Beatniks; graffiti, rock bands and political street theatre: you know what I mean. The state repression and terror that followed the Naxalbari movement left a strange bitter aftertaste in our cultural imagination: young men cheering for Chairman Mao as their chairman and dying in hundreds in false encounters, disbelief in politicians who appeared once in five years asking for votes, and a general sense of fear, disillusionment, and insecurity that pervades even now. But I’m speaking of the experiences of the so-called “educated classes” here, urban people, and not the majority who live in the villages. We know very little of what passes in their minds.

Is there a distinctive Bengali or Bengal-area comics tradition, distinct from that in say North India or Bombay? If so, how did that local tradition shape Drighangchoo?

Yes, as there probably is in every state territory in India, though you’ve to dig them out throughout the subcontinent. We are horrible at archiving things, except for kitschy stuff. If you’re speaking of comics in India, the most visible ones are the syndicated stuff: archetypal Indrajal Comics. Next are the derivative ones: Chacha Choudhary, Amar Chitra Katha, Diamond Comics, Tinkle and the like, also championed by big publishers. The third is experimental, inspired but not derivative, local work; what I’d like to call our indigenous comics tradition. In Bengal, if you exclude the narrative tradition of the patachitras (which are hand-painted scrolls of unfolding sequences of illustrations by village artists, which is a different narrative tradition altogether), work on sequential narratives in print had begun sometime in the early twentieth century. The first example of it is probably a four-paneled story by Sukumar Ray drawn sometime between 1915-1920. Cartoons were popular in print since the 19th century, though, mostly in newspapers that worked within the caricaturing and lampooning conventions set by the 19th century British magazine Punch. Sometime during the Second World War, the comics form first gained popularity here, courtesy the war comics supplied aplenty by the propaganda machinery of the Allies.

I don’t know what happened in East Pakistan (presently Bangladesh), but here in West Bengal, under Indian territory, that is, comics first appeared in the children’s monthly magazine Shuktara (Evening Star) in the early 1950s. These were derivative, though the artist made attempts to “Bengalicise” the funny acts of two young boys, Hada and Bhoda. I’m not sure, but judging from the style of drawing, the original creator of this comics was probably the Bengali illustrator and artist, Pratul Chandra Bandopadhyay, and not Narayan Debnath, now known as the grandfather of Bengali comics. (I’ve shared a few of them from my personal collection with The Comic Book Project at Jadavpur University.)

Later, this comic strip was run by Narayan Debnath, an extremely prolific artist, who went on to draw comics for the Bengali children’s magazine industry for the next fifty years. A conservative, Debnath however stuck to derivative funny capers (Baatul the Great from a Norwegian comics; Bahadur Beral, Nante Fante, etc.); some lame detective stories set in Calcutta featuring a dhoti-clad detective Nishit Ray chasing a master criminal called Black Diamond who always wears Western clothes; and a James Bond like secret agent (minus the wine, the girls, and the sex) called Kaushik who kicks out a secret blade from his left shoe at the slightest provocation and punches with a white metal glove worn on his right hand. By the 1960s, many Bengali-language magazines for children and young boys and girls were publishing comics. As were the newspapers: cartoonist Pratul Chandra Lahiri, or PCL as he was more popularly called, drew a daily comics in the Bengali newspaper Jugantar called Sheyal Pandit (The Learned Fox) under the pseudonym Kafi Khan, and Khuro (Old Uncle) for the Ananda Bajar Patrika.

Prasad Ray or Mayukh Choudhury (whom I mentioned earlier) was a giant of this time. He didn’t go with the newspapers but made his life by illustrating book covers and drawing comics for the magazines. He is the one, I’d say, who can be considered the true face of the indigenous Bengali comics tradition. He drew recklessly, with deeply inked shadows, and yet so particular. You could see animals frozen in motion, the exact snarl of a lion, the flight of wild horses. He narrated adventures of his own creation: adventure stories set in Africa or in ancient India at the time of Alexander’s invasion, Jack London-esque animal adventures, and crazy mystery tales. His best work, probably from the early 70s, is a story called “Aguntuk” (The Stranger) about a humanoid Martian called Jura (who has pointy ears, retractable claws like today’s Wolverine, but noticeably Bengali features) who fights to death against his Martian clansmen to save a Bengali boxer friend. I remember reading it again and again during my adolescence, in a well-thumbed compilation of his comics, and shivering with trepidation before going over to the final climactic fight between Jura and Monthap, the Martian chieftain.

By the middle of 1970s, however, syndicated comics had appeared through Times of India in the form of Indrajal Comics, and these local forms lost their ground. Debnath, who's ailing now, continued working, in a career that spanned more than half a century. But Prasad Roy died in utter penury, uncared for, and in great pain. In the magazines, there were people continuing in Bengali, though less and less noticeably: Gautam Karmakar drew space operas and time-travel stories throughout the 80s and 90s; Sarbajit Sen drew the Adventures of Timpa (a Tintin-like character moving in the streets of Calcutta) in the early 90s. By this time, there was a splurge of American syndicated comics in the magazines and newspapers, and many like Sarbajit Sen stopped working and moved into other fields. It was pathetic, really, to find Bengali comics artists single-handedly trying to churn out tales of caped superheroes, and trying to compete for attention against the syndicated comics in smudgy ink and cheap newsprint.

The only difference that I've had seen between Bengali comics and North Indian comics (I'm speaking of Hindi-language mainstream comics) of this period is that there were some experiments in science fiction comics without recourse to the Flash Gordon model. The Bengali young adults magazines Kishore Bharati and Sandesh published some of them during the 1990s. Shuktara stuck to the 70s model, publishing repetitive works by Narayan Debnath; the chief player in this field, Anandamela, heavily depended on translating and popularising syndicated comics.

And yet, somewhere in between, there had been people trying to break the mold, people like Mayukh Choudhury and other comics artists about whom we know next to nothing. Tintin-da (Dr. Abhijit Gupta) has in his collection a small comics strip from the early 1970s, drawn by a young Naxalite who wanted to narrate the encounter killing of his comrades through the medium of comics. Researchers working for The Comics Book Project at Jadavpur University have unearthed small-press indigenous comics in Kerala, in the Malayalam language…. And I’m sure they can be found in every other Indian language as well, if someone is keen on finding them… As whether the Bengali comics tradition inspired us, it’s difficult to say. But we were definitely moved by the total absence of serious comics here, and utterly disgusted by the derivative nonsense.

I noticed an article in Bengali on patua in issue two.

Yes, the author, Sujit Kumar Mondal is an assistant professor of Comparative Literature at JU and a folk-history researcher. In his piece, he outlines a brief history of the Bengali patua tradition, their tools of craft, and argues for the need to revisit to the older, indigenous forms of the patachitras, that is, if we are to get serious about comics.

Do you think there is a real link between the region's comics and such local visual storytelling traditions?

No, I don’t think so, unless people here are referring to something like Jungian “collective unconscious”. In fact, it’d be hypocritical to say that there’s a link, for there isn’t any. Our comics artists have been almost successful in severing our contact with the past. Some revivalist attempts have been made in the field of visual art, most notably by the Bengali painter Jamini Roy, but none by comics artists. Nowadays, the bitter truth is, most people on the field are busy regurgitating young adult fiction written by Bengali authors in the comics form, modeled on The Adventures of Tintin, and calling those “graphic novels.” They are content with that.

You mentioned "little magazines," self-published literary magazines. I was just reading a couple of articles on the subject of Bengali and Marathi little magazines in Art Connect, from the India Foundation of the Arts. Did such literary magazines influence the shape of Drighangchoo?

Yes, in a way, though you need to differentiate between big “little magazines” (those who take advertisements from the state and commercial establishments and follow a merchandising model), and the small “little magazines” (who seriously stick to the non-commercial self-publishing model).

The first ones, who once started small, and in most cases as offshoots of the erstwhile avant-garde leftist cultural movements that rocked the 1960s and 1970s, are more visible and are generally identified as “little magazines” here. The second ones are more difficult to find, but they are the ones that have tried exploring alternative possibilities, or at least, kept up the enthusiasm before they folded up. Team Drighangchoo was a mixed group: Pinaki-da was one of the big names of the mainstream book cover design industry in India; Anindya-da had experience in Bengali little magazine publication; Debapriya ran a poetry magazine when she was an undergraduate student; I too had three small-press little magazines on my belt. When thinking on Drighangchoo, though, we all decided it would be a not-for-profit initiative, unlike the little magazines that flood the Kolkata literary scene.

Were there other sorts of publications you had in mind, within comics publishing, literary publishing, et cetera.

Strictly speaking, no.

Sarbajit Sen has a major presence in the magazine. You talk about him as a kind of a mentor figure. Who is he, and what was his role in the magazine?

Sarbajit Sen is a cartoonist, a comics artist, a painter, and a documentary filmmaker. He is also a book designer for the small press and alternative Bengali publishing industry (many books, like the first edition of Akhtarujjaman Elias’s collection of short stories, have been illustrated by him). His Adventures of Timpa was quite a rage in the early nineties, and I came across his work in many unlikely places, before meeting him for the first time in 2008. He was working on a book-length comic in Bengali on the politics of climate change then. We became friends soon after: someone you could always consult when in doubt, or have an inspiring conversation on comics, literature, and films.

Though he wasn’t formally involved in the making, he was very enthusiastic about Drighangchoo from the beginning, and readily agreed to contribute pieces for our issues. He is the one who introduced us to the works of older Indian cartoonists and European comics artists, and made us seriously enthusiastic about comics. He’s consistently optimistic about the comics scene in India (something I’m not), and I have found him putting in great care and effort for every task at hand, whether it be his own comics, a book cover for a small press publication that doesn't offer compensations, or sets of giant posters and banners for many small peoples' collectives that throw his artwork to the bins once the show is over.

Have any of Drighangchoo's contributors continued as cartoonists/comics artists/illustrators?

Yes, that I’d put as one of the achievements of Drighanchoo, that is, if we had had any. Post-Drighangchoo, Pinaki-da is working on his graphic novel, Sarbajit-da is busy on a number of projects. Rimi-di (author and academic Rimi B. Chatterjee) has been editing a number of comics books with mainstream publishers after her comics intitiative Project C fell through. Madhuja Mukherjee has rendered Nabarun Bhattacharya's novel Kangal Malshat in the graphic form. Among our younger contributors, Vaswar Mitra, now an architect, is working on a comics rendition of some stories by Subimal Misra (an anti-establishment Bengali author who sticks to writing for Bengali little magazines). Pramit Basu, who is currently studying at the National Institute of Design, is working on his own comics. Tito (Arnab Chakraborty), who was an eager undergraduate then, went on to initiate and publish the university magazine Hypocrite Lecteur, and now close to publishing his first comic book.

Why was Drighangchoo discontinued ultimately?

There were many reasons for its discontinuation, but I'd identify the primary one as a lack of enthusiasm among the five editors, including myself. I don't know about the others, but I can tell you of my reasons, though.

Initially, the magazine was enthusiastically received by a small group of people in Kolkata. Since we weren't able to pay authors, we relied on voluntary submissions. We were also insistent on telling people that we were interested in making comics for adults, though not many of our friends understood what we were saying. Nevertheless, we made a good start. The best thing I personally got of the Drighangchoo experience was to make friends with Sarbajit Sen, who agreed to contribute to all our three issues, and also young people like Vaswar and Tito. Anyway, we were selling quite a number of copies in the campus and got friends to transport a few copies to Delhi and Bangalore.

Problems cropped up after the second issue. Bookkeeping wasn't a strong point with us, and there were many among our friends who had taken a number of copies, sold them, but didn't turn up the money. A printer charged us exorbitantly for the second issue, the magazine was seriously short of funds, and the sales did not recover the production costs even marginally. You see, the seed money for each issue mostly came from me and two other research fellows. Once we ran out of our fellowships in 2011, and since we weren't taking commercial ads, there was no way to generate the money. Yet the third issue came out: an issue featuring an interview with French comics artist David B whom we had managed to meet on his visit to Kolkata.

Enthusiasm also became a major point: I and Debapriya were the only ones who did the running around part. As it turned out I then had a major work load: from soliciting authors and breathing on their throats to keep the deadline, correcting pages of the individual copies, designing the mag, negotiating with the printer, buying paper, to selling the printed magazine to people I know, and carrying it to different bookshops. I was also working hard on my PhD thesis then, and terribly close to submission. So was Debapriya. Consequently, there was no issue in 2011, despite quite a number of phone calls and emails.

In 2012, we got temporary project jobs at the varsity. That was when Debapriya and I met once again and thought of making a final effort to revive the magazine. A submission request was put up, and contributions started pouring in, ones by twos. But then, again, after many emails and phone calls, no one except us two turned up for the meetings we had called. It was then I decided I had enough, and decided to fall back, silently, without raising any issues. Nothing followed in my absence. As it stands now, the magazine is dead: and chances of its revival are, to be honest, none.

I had a number of talks with Sarbajit-da after all this happened. He's still working on comics, and despite his years, more optimistic on the growth of serious comics consciousness in India than I am at present. He told me that the consciousness doesn't come from a blind aping of Alan Moore, Art Spiegelman, and Thomas Ott, and the vague participatory glee of Indian comic-cons. It's got more to do with an Indian comics artist relating to his surroundings, the way Eisner related to his life at the New York ghettos, and working like an medieval master artisan on his craft rather than a machine operator working on mass-produced consumables. He advised me to work on my own comics: an advice I'm yet to follow. He also told me that nothing is lost. Reading your first email to me, after I had thought everything about Drighangchoo was all buried and forgotten, I guess he was right.