Adapted from Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature (University Press of Mississippi, 2012).

Adapted from Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss: How an Unlikely Couple Found Love, Dodged the FBI, and Transformed Children’s Literature (University Press of Mississippi, 2012).

Cushlamochree! In April 1942, Mr. O’Malley — part confidence man, part fairy godfather — met five-year-old Barnaby, and the comics pages had a new classic. When the first collection of the strip was published the following year, newspapers and magazines sought interviews with the strip’s creator, Crockett Johnson. He talked to journalists, but, in his wry, laconic way, he typically said very little about his life before Barnaby.

But before Barnaby, there was Crockett Johnson. And before Crockett Johnson, there was David Johnson Leisk.

He was born in New York City, on October 20, 1906. His roots go back at least six generations in the Shetlands — rocky, mostly treeless islands halfway between Scotland and Norway, governed by the latter until the late fifteenth century. His blue eyes and blond hair hint at this Scandinavian ancestry.

Seeking professional opportunities, Johnson’s father — the third eldest of ten children — left the Shetlands just after the turn of the twentieth century. In New York City, he found work as a bookkeeper at the Johnson Lumber Company, and fell in love with department store saleslady Mary Burg, a German immigrant.

In October 1905, they married, moving into a six-storey apartment building at Manhattan’s 444 East 58th Street, a block west of the East River, and a block south of where the Queensboro Bridge (the 59th Street Bridge) was then under construction. A year later, David Johnson Leisk was born in this apartment. His parents named him “David” for his father, and “Johnson” for his father’s place of employment. At the time of David’s birth, Mary was 29 and David Sr. was 41, relatively old for first-time parents. On May 27, 1910, Else George Leisk was born. As a tribute to her father’s love of literature, they gave Else a middle name in honor of novelist George Eliot. By 1912, the Leisks had moved out of their Manhattan apartment, and into the suburbs — Queens.

As Dave’s grandfather had done, his father built things — including a sailboat — in the backyard, and took Dave sailing on Long Island Sound. So begins his life-long love of sailing, and the reason that, when Harold draws a boat in Harold and the Purple Crayon, he draws a sailboat. When Dave was a boy, he and his sister spent many a Sunday like this: Their father rowed a small boat out into the water, and they dove off the boat into the ocean. However, pollution soon ended the swimming. Flushing’s sewage emptied into the bay, driving away fish and bathers. In 1915, the Board of Health advised against swimming in Flushing Bay, and after 1917 no one swam there.

Perhaps his fondness for the unpolluted outdoors led Dave Leisk to a comic strip about frontiersman Davy Crockett. To distinguish himself from the other Daves in the neighborhood, Dave Leisk borrowed the name “Crockett” from this cartoon. He later said that he adopted “Crockett Johnson” as a pen-name because “Leisk was too hard to pronounce,” but he began using the name “Crockett” in childhood. In 1934, he started signing his work Crockett Johnson, and by 1942, the phone book listed him under that name. Well before his childhood nickname became his professional name, he began using Dave privately. But private and public were closer than he was willing to acknowledge. Crockett Johnson’s works were always a reflection of Dave Leisk. It’s no coincidence that his most famous character, Harold, is also an artist.

In this respect, Dave took after his father. While the elder David Leisk was a regular guy who had a weekly pinochle game with the guys from the block, he was also an avid reader and writer. He read history, and learned the Declaration of Independence by heart — doing so well before he became a naturalized citizen in 1923. He read poetry and wrote poetry, including one poem about his native Shetlands. A boat designer and sailor himself, David Sr. followed the 1920 America’s Cup race, dispatching a full news story to his hometown newspaper, the Lerwick Times. His son inherited not only his father’s literary and journalistic inclinations, but also his slow, deliberate manner of speech.

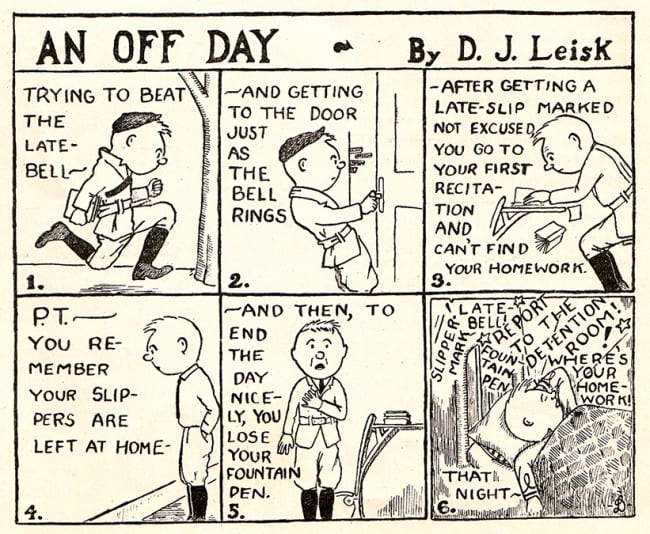

Dave Leisk’s earliest creative work appears in The Newtown H.S. Lantern, the school magazine of Newtown High School, which he began attending in the fall of 1920. The publication’s second issue, from March 1921, included “An Off Day,” a cartoon by 14-year-old D.J. Leisk chronicling the exploits of a round-headed schoolboy identified only as “you.” As Jeet Heer and Chris Ware point out (in their pieces for The Complete Barnaby Volume 1), these early cartoons bear the influence of Gluyas Williams, whom Ware calls “the original ‘clear line’ artist.” Not yet using his famous pseudonym, Leisk signs his work — in the bottom right corner of the sixth and final panel — with a cursive “D” transposed onto a cursive “L,” the sigil that would become his signature for his high school work.

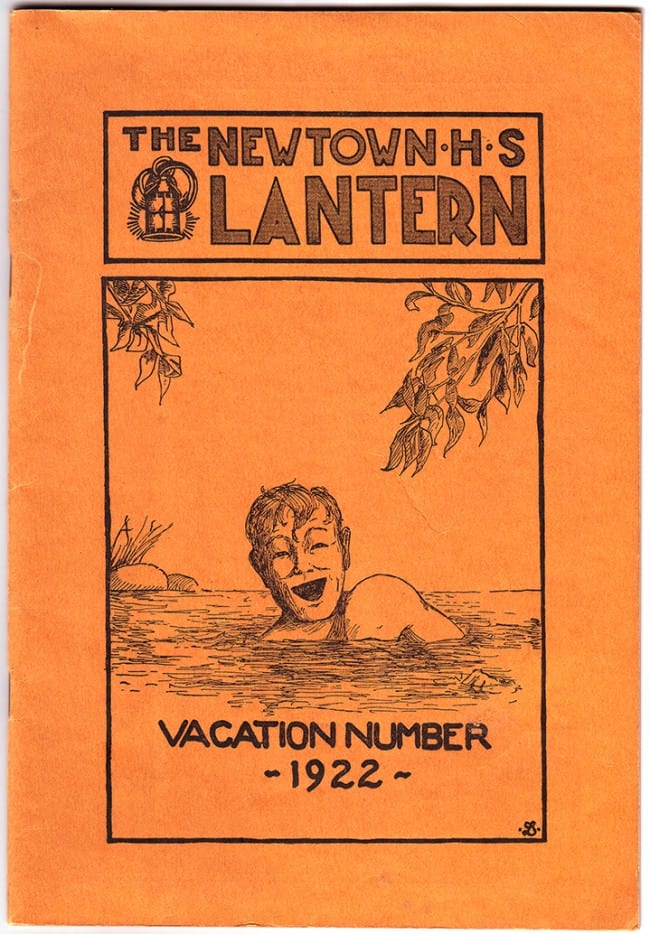

He drew his first cover for the Lantern’s May 1922 issue. Framed by tree branches, a laughing boy’s head rises above the surface of what may be Linden Lake — in the park two blocks south of his home, and directly across from P.S. #16, where he went to grade school. Suggesting his affinity for this subject, his cover for the May 1923 Lantern features an illustration of a young man dozing by the edge of he lake. If his early cartoons are any guide, Dave knew that he was a dreamer, but was uncertain where those dreams might lead.

On June 26, 1924 David Leisk graduated along with his class of 149, “the largest ever graduated from Newtown High School.” As the class photo discloses, it was a diverse group, reflecting the area’s ethnic mix of Anglo, German, Swedish, Italian, Jewish, and African people. Neither a star athlete nor an ambitious student, Dave was a tall, athletic, easy-going 17-year-old, well-liked by his peers. In that class photo, he sits front and center, scrunched casually between his classmates. Dressed in a dark suit and white shirt, he smiles broadly, as his blue eyes look out at the photographer, who was then taking what is now one of the earliest known photographs of Crockett Johnson.

Though not a highly motivated student, his natural intelligence landed him on the Honor Roll of Newtown High School students who earned 90 per cent or above in New York State’s Regents’ examinations for English. He won a scholarship to Cooper Union, in lower Manhattan. He commuted there for two semesters, taking classes in art, typography, and drawing from plaster casts. By the Spring of 1925, his father had died, and Dave’s college career abruptly ended. At age 18, he dropped out to get a job and support his family.

Department stores were thriving in the ’teens and ’20s — Marshall Fields in Chicago, Filene’s in Boston, and Macy’s in New York. On the strength of his Cooper Union art courses, Dave in the winter of 1926 became Macy’s advertising department’s Assistant Art Director, a position he described as “a glorified office boy.” Working in the advertising department gave him a chance to develop skills in typesetting and illustration, but few chances to express his creative side. All ads had to conform to Macy’s style, using its distinctive typefaces and trademark red star. He did not stay at Macy’s for very long, quitting just before he was fired for wearing a soft collar instead of a regulation stiff one.

After Macy’s, Dave got a job hefting ice in an ice house. It is possible, too, that during 1926, he played semi-professional football for the Flushing Packers. Just two weeks after his 21st birthday, he returned to publishing, becoming the first art editor of Aviation (Aviation Week today). During his time at Aviation, he began taking typography and graphic design classes at New York University’s School of Fine Arts. He studied with Frederic Goudy, a master of print design who invented more than a hundred typefaces, and who may have influenced the precise minimalism that defines Johnson’s artistic style. Goudy described his own work as “simple[;] that is, it presents the simplicity that takes account of the essentials, that eliminates unnecessary lines and parts,” an aesthetic echoed by Johnson’s later view of his illustrations as “simplified, almost diagrammatic, for clear storytelling, avoiding all arbitrary decoration.”

Beyond what he was learning at school, Dave was receiving an on-the-job education in layout and design. In early 1929, publisher James McGraw bought Aviation, adding it to his portfolio of business periodicals. During the corporate reshuffling that followed, Dave became Art Editor of a half-dozen McGraw-Hill trade publications. However, the stock market crashed less than eight months later. The company’s fortunes declined, circulations dropped, and some magazines disappeared entirely. McGraw-Hill laid off employees of all magazines; Dave and others who remained received reduced salaries.

As many in his generation did, Dave turned left. He joined the Book and Magazine Writers Union. He read The Daily Worker and New Masses. He befriended like-minded people, such as Charlotte Rosswaag. He also fell in love with her.

Like Dave’s mother, Charlotte was a strong-willed German. Born in 1908, Charlotte emigrated to the United States with her family in 1915. She shared Dave’s progressive politics, and could be blunt, though her sense of humor softened the edges of her frankness. By the mid-1930s, Dave and Charlotte were married and living with their two dogs, in a garden apartment on or near Bank Street in Greenwich Village. She was a city social worker, and Dave continued to do magazine layout for McGraw-Hill.

He began to contribute to the Communist weekly New Masses. His first cartoon, published 17 April 1934, mocks self-professed experts on communists. In a cartoon published three months later, he goes after not only the rich in general, but President Roosevelt in particular. Billionaire industrialist J. P. Morgan reclines on a luxury liner’s deck chair. “CORSAIR” on the life preserver links Morgan to piracy, likening the captain of industry to the captain of a pirate ship. A young man delivers a message: “Radiogram, Mr. Morgan. The White House wants to know are you better off than you were last year?” Johnson suggests that President Roosevelt is more concerned with the wealthy than the needy, implying that, yes, the rich are doing fine, but how about everyone else?

In 1932 and 1933, 24 percent of Americans were unemployed, up from 3.2 percent in 1929. Though the unemployment rate would drop to 21 percent in 1934, the nascent New Deal had yet to produce major results. It was a time when people went on hunger marches, when police shot strikers, and when general work stoppages shut down major U.S. cities. As Michael Denning writes, “The year of the general strikes—1934—was also the year young poets and writers proclaimed themselves ‘proletarians’ and ‘revolutionaries.’” In his cartoons, Johnson announced his sympathy with proletarians and revolutionaries.

He signed his first cartoons simply “Johnson.” By August 1934, he began signing them “C. Johnson,” sometimes reverting to “Johnson” and once to “C. J. Johnson.” Whatever name appeared on the image itself, New Masses nearly always printed his byline as “Crockett Johnson,” the public debut of his pseudonym. The first cartoon to bear that name was published on 7 August 1934 and showed a wealthy capitalist wife complaining, “Just because your greedy workmen decide to go on strike I can’t have a new Mercedes. Somehow it doesn’t seem fair.” Thoughtful, soft-spoken art editor Dave Leisk had become radical cartoonist Crockett Johnson.

In June 1936, Johnson joined the staff of New Masses, earning between twenty and twenty-five dollars per week. As the publication’s art editor, Johnson would redesign the weekly with the aim of increasing circulation beyond its radical readership. Working with Rockwell Kent, the best-known and most successful American printmaker, Johnson planned an easier-to-read layout and design for New Masses, adding more artwork and pictorial covers. Johnson explained, “The idea now is to go in for decorative covers that are not too blatant (and often non-committal) about our editorial viewpoint. Titles, when we use them, will pose a question rather than dogmatically state a fact. The intention is of course not to deceive the prospective reader, but to try to avoid having him react unfavorably to our position as stated by headlines or an unpleasant or too strong political cartoon before he’s bought the magazine and read all the facts we present.” The first redesigned New Masses appeared on 15 September: Instead of listing article titles, as previous issues had, the cover bore a bold Kent illustration of a woman’s profile, facing right. Her right hand holds a pole, with a blank flag waving just over her head. Left hand cupped to her open mouth, she calls out. Her gaze and the angle of her hand point to the right side of the page, inviting the reader to open it, and to discover just what has made her so animated.

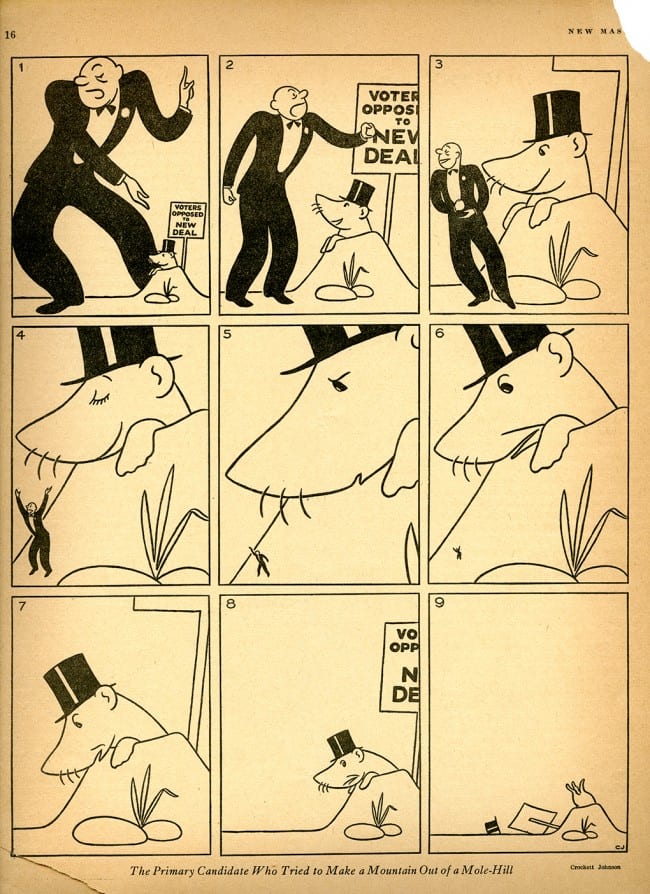

Though that issue featured news with a distinct Party flavor, Johnson’s New Masses cartoons display his evolving politics. As the radical Left began to warm to FDR later in the 1930s, so did Johnson. A May 1938 cartoon, “The Primary Candidate Who Tried to Make a Mountain Out of a Mole-Hill,” displays Johnson’s changed attitude toward the New Deal and shows the clean, minimalist style that would become the hallmark of the artist’s work. In the New Masses cartoons and in all of his subsequent work, Johnson practiced what Scott McCloud calls “amplification through simplification.” He strips images down to their essential components—a curved line for a man’s open mouth, three short lines for a mole’s whiskers, an oval for a rock. As McCloud observes, “If who I am matters less, maybe what I say will matter more.”

On August 23rd 1939, the Hitler-Stalin pact sent the radical Left into disarray. Having led the fight against Fascism, many U.S. Communists were shocked when Stalin and Hitler agreed to stop war preparations against one another and to instead divide Europe into two spheres of influence. Literary critic Granville Hicks, a New Masses contributor since 1932, quit the Communist Party and resigned from the magazine’s editorial board.

Some younger staff members followed, but Johnson remained committed to the cause. In November, Johnson spoke with Syd Hoff about an idea for a cartoon based on Marx’s idea (and Lenin’s claim) that revolution is the locomotive of history. Published in the New Masses on 28 November 1939 under the pseudonym A. Redfield, Hoff ’s drawing shows the locomotive’s relentless progress over obstacles. A group of former supporters marches away from the train tracks, with leaders bearing a sign announcing themselves as “The ‘Russia Was Okay Until . . .’ Society” and followed by smaller groups carrying smaller signs such as “Until Trotsky Left,” “Until Kerensky Left,” and “Until that Pact.” Despite the optimism of Johnson, Hoff, and others, the pact marked the beginning of the end for New Masses. Its support, both financial and otherwise, dwindled until it finally ceased publication in 1948.

![A. Redfield [Syd Hoff], "When the locomotive of history takes a sharp turn," New Masses, 28 Nov. 1939.](https://the-comics-journal.sfo3.digitaloceanspaces.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/8_Redfield_locomotive-650x412.jpg)

Dave and Charlotte decided to divorce.

Baltimore native Ruth Krauss, recently divorced herself, returned to New York City. At a party in the fall of 1939, the outgoing, energetic Ruth met the wry, laconic Dave. He was tall and taciturn. Seven inches shorter, she was slim, exuberant, and ready to speak her mind. Her exuberance drew him out of his natural reticence, and into conversation. His calm, grounded personality balanced her turbulent energy. They were complimentary opposites who felt an immediate attraction toward one another. As Ruth liked to say, “We met and that was it!” Within a year, she moved into his West Village apartment, he left New Masses, and he embarked upon a new career as a comic-strip artist.

After creating a minor classic in his wordless “The Little Man with the Eyes” (which ran in Collier’s from 1940 to 1943), in the early 1940s Johnson stumbled upon the idea that would make him famous: a precocious 5-year-old boy, and his pink-winged, cigar-champing fairy godfather. At the age of 35, Crockett Johnson had created a comic strip that would make him famous: Barnaby.

Philip Nel is Professor of English and director of the Program in Children’s Literature at Kansas State University. His latest book (obviously) is a biography of Crockett Johnson and Ruth Krauss, over a dozen years in the making. With Eric Reynolds, he is co-editing The Complete Barnaby for Fantagraphics.