“Producer of preposterous pictures of peculiar people who prowl this perplexing planet”

“Producer of preposterous pictures of peculiar people who prowl this perplexing planet”

– Basil Wolverton’s letterhead

Dear Uncle Foopgoop,

I'm still wrestling with writing about Wolverton. Gotta say that new Fantagraphics Scoop Scuttle collection is really the berries. The more I look, the more I see. The more I see, the more I laff.

Uncanny how—in some ways—these 1940s stories prefigure the MAD comic books. They take the tropes of past screwball cartoonists and build on them, so they are sort of a missing link between Count Screwloose and Superduperman!.

But they are their own thing, too. As much as he learned from other cartoonists, Basil also made his own rules (for instance, as you once put it to me, living on the wrong coast) and then methodically ignored them, in the best form of Screwballism.

I'm starting to think Wolverton just might be the greatest of them all, Saul.

Sincerely,

Tall Pumey

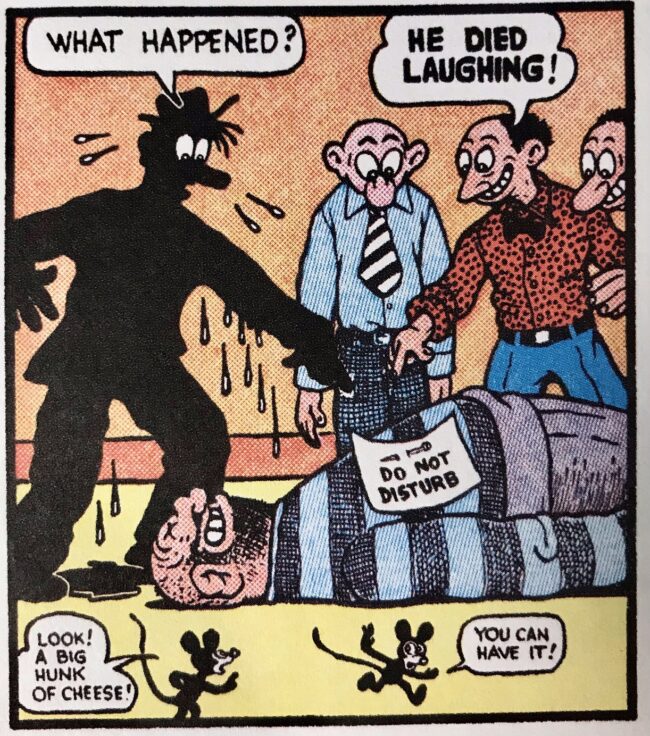

In the back pages of the obscure 1944 comic book, Candy Comics, there’s a Basil Wolverton story filled with unforgettable funny phallic nose-play. When reporter Scoop Scuttle questions a street sweeper bestowed with the stupefying and typically Wolvertonian surname of “Foopgoop,” he’s absentmindedly pinching the man’s bulbous snoot as tiny pain stars radiate outward. No attention is paid to this strange behavior.

A few panels later, the protruding proboscises of two characters casually press together like gherkins nuzzling.

Before this four-page schnozzle ballet concludes, Scoop has bonked, honked, and rubbed beaks with six Foopgoop brothers and no one says anything about it, which makes it funnier and funnier. One has forgotten the plot of the story, becoming delightfully lost in the subtext, suggestive of what I and my boyhood chums used to call a “swordfight.”

Before this four-page schnozzle ballet concludes, Scoop has bonked, honked, and rubbed beaks with six Foopgoop brothers and no one says anything about it, which makes it funnier and funnier. One has forgotten the plot of the story, becoming delightfully lost in the subtext, suggestive of what I and my boyhood chums used to call a “swordfight.”

On top of this bizarre action is a casual discussion of suicide, one of many examples of India-ink-black humor in Wolverton's 1940s comic book stories (see also the early years of Rube Goldberg's Boob McNutt, 1918-1920, and, of course, those Jack Cole comics which were contemporaneous with Scoop Scuttle). This story, with intoxicating screwball comedy squeezed out of a sober subject, numerous side and background gags, frenetic energy, and masterful, singular cartooning, is like reading one of the celebrated Kurtzman and Elder/Wood/Davis MAD comic book stories from 10 years later—only the satire is less specific, weirder, and... at times, dirtier. The resemblance between Wolverton's humor comics of the 1940s and those insane MAD comic book stories of the 1950s (and all the inspired imitations) is notable and significant.

It makes sense to me that Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman—prime shapers, among a handful of others, of the taboo-breaking underground comics movement of the 1960s-70s and beyond—imprinted on Wolverton’s work at an early age. The underground ethos quietly existed in comics, albeit in disguise, long before Zap and Arcade, and here's an example.

When I stop to wonder if I am seeing subversive, frisky undertones where they weren’t intentional, it helps to remember Basil Wolverton performed comedy routines on stage as a young man in a circuit that took him through the cities of the Pacific Northwest and later hosted radio shows in the late 1940s. Surely there were some elbow-in-the-ribs-wink-wink type gags performed for a chuckling public.

Wolverton’s sly humor comes through in a set of home recordings made in the 1970s and produced in 1992 by Ray Zone (who wrote an excellent essay on Wolverton called “Boltbeak: The Art of Basil Wolverton” which appears in the scholarly Journal of Popular Culture, volume 21, issue 3, 1987) and released on the Sympathy for the Record Industry label as Wolvertunes, a seven-inch red or blue transparent vinyl EP festooned with 3-D Wolverton art.

Wolverton opens a ukulele song with: “Hello. This is your o-o-o-O-O—old cartoonist friend, Basil Wolverton.” (He pronounces his first name “bay-sil”.) By leaning into the vowel and stretching it out, Basil infuses a seemingly innocuous self-introduction with a gag that brings to mind the twistings and turnings of his outrageous caricatures.

Similarly, he leaned into those big nose drawings in his comic book stories. And he leaned into those caricatures—boy howdy, did he lean. In fact, one would be hard-pressed to find a gag or a caricature into which our o-o-o-O-O-old cartoonist friend did not lean into. It is the essence of his style: over-the-top-and-under, like a pile of spaghetti.

Wolverton’s technique of layered gags, inserting them where one would not normally expect to find them, such as written on a sign held by a hand sticking out of a hole in the ground, is also the mainspring of Screwballism. Nested gags, over-the-top slapstick, offbeat and off-color humor are all hallmarks of both Screwballism and Wolverton's masterful comics, which celebrate the absurd nature of the world. With his singular vision, Basil Wolverton added novelty to an already novel form (and I don’t mean graphic novel!).

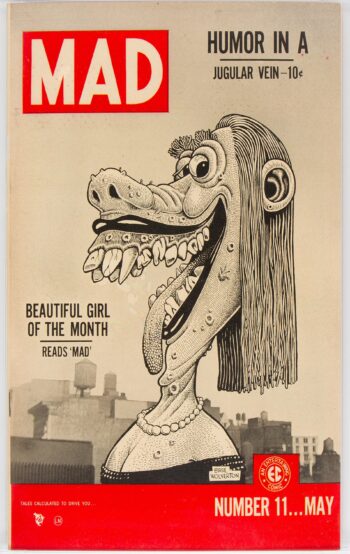

There’s nothing else quite like a Basic Wolverton comic book story. The first thing that strikes you is the art—a singular mixture of grotesque distortions and OCD rendering. His work is simultaneously inviting and repulsive. The style is so strange, one wonders how any of it was ever published—and, in truth, Wolverton's work was mostly relegated to the back pages of comic books as "filler" and tertiary features. It took the help of two other cartoonists, Al Capp and Harvey Kurtzman, to amplify Wolverton’s subversive strains and create two iconic images in American comics: Lena the Hyena (1946) and the cover of MAD #11 (1955).

The Foopgoop brothers story, the naughty nascular nonpareil described above, appears, with 47 other, equally dizzying comic book stories from the 1940s and '50s, in a new trade paperback volume entitled Scoop Scuttle and His Pals: The Crackpot Comics of Basil Wolverton. Written, edited, designed and produced by Wolverton’s biographer, the indefatigable Greg Sadowski, this book provides some powerful ammunition to those who would fight to place Wolverton (1909-1978) among the most brilliant humor cartoonists of the 20th Century.

The impeccably restored stories in this collection have been dredged up from the back pages of lesser-known, long-ago comic books like Silver Streak, Daredevil, Candy Comics, Comic Comics, Black Diamond Western, Weird Tales of the Future and Ibis the Invincible. This delectable banana and strawberry-colored volume represents the latest in an impressive library of Wolverton volumes published by the faithful fiends at Fantagraphics.

In the last decade, Foopgoopgraphics has released Sadowski’s exquisite two-volume biography of Wolverton (Creeping Death from Neptune and Brain Bats of Venus), a large-format, to-die-for collection of Spacehawk stories, a very cool collection of Culture Corner (complete with pencil roughs!), and The Wolverton Bible, a mind-boggling art book of Wolverton’s devout, “straight” illustrations from scripture (matched in our era by Robert Crumb’s The Book of Genesis, one of a few examples of Crumb following in Wolverton's tracks, intentionally or not).

One might assume that, with this latest collection of filler material, Fantagraphics is scraping the barrel, but not so. The material represents some of Wolverton's finest work in humor comics and includes an almost-masterpiece, the Scoop Scuttle series.

The volume is divided into four sections, each presenting complete and impeccably restored runs of four long-overlooked Wolverton humor comic book series:

» Scoop Scuttle (18 stories, 1940-45, Lev Gleason and William H. Wise & Co.)

» Mystic Moot and His Magic Snoot (13 stories, 1945-48, Fawcett)

» Bingbang Buster (13 stories, 1949-51, Lev Gleason)

» Jumpin’ Jupiter (4 stories, 1951-52, S.P.M. Publications)

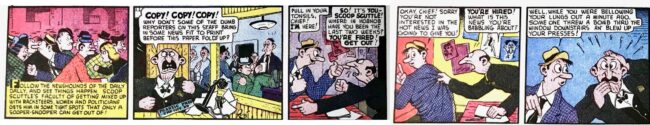

Scoop Scuttle is a reporter for the Daily Dally and gets his assignments from Frantic Fred, the City Editor (shortened in the stories to "Ed" for the rhyme). In his scripting, Wolverton creates plots that are as elastic and surprising as his people.

Scoop Scuttle is a reporter for the Daily Dally and gets his assignments from Frantic Fred, the City Editor (shortened in the stories to "Ed" for the rhyme). In his scripting, Wolverton creates plots that are as elastic and surprising as his people.

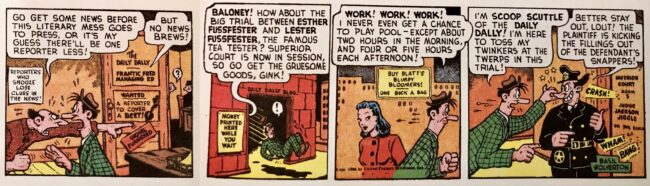

Lamp this, Len: in one story, Scoop falls asleep observing a courtroom trial and dreams he is fighting Nazis in the desert. In another, he is sent to Germany to interview Hitler, and that one isn't a dream! Scoop attends city council meetings, chases fires, and makes the mistake of going to inferior court instead of superior court (rim shot, please). We meet a parade of eccentrics like opera star Screamo Adenoido, the millionaire vitamin pill magnate Varicose Vane, and Lester Fester, who has invented a left-handed mouse trap. Sccop and his fellow citizens tend not to get too far into a plot; they are too busy pinching, punching, pursuing, trash-talking, or sometimes even shooting each other in these four-color operettas.

Wolverton infused a humming, frenetic energy into his Scoop Scuttle stories. People are wide-eyed, dashing, zooming, wildly gesticulating, yelling, shouting, climbing over each other, and—as previously noted—pinching all available noses. This mania would be at home in the rapid-fire Howard Hawks screwball comedy movie about newspaper people, His Girl Friday, which came out in 1940 and may well have been an inspiration to Wolverton for Scoop, created the same year. It's also a device Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder sometimes used to astounding comic effect in MAD, and one that is the raison d'être for the gaudily screwball film It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World (1963, poster by MAD artist Jack Davis)... but I digress.

Unlike anything ever seen in a film, labeled “screwball” or not, is Scoop Scuttle’s insane, gag- and pun-ridden slangy dialogue, delivered in snatches of rhyme and tongue-twisting alliteration. In one splash panel, Frantic Fred, City Ed, proclaims: “Doggonnit! The Daily Dally will drop in the dump if the dawdling droops who dish its drivel don’t drag in some decent dope before deadline!” Imagine Cary Grant rattling that off! At a diner, a salivating Scoop tells the waitress, “I love to gorge, by George, so fetch me a flock of frittered filberts fried in fragrant fusel oil, old goil!” In Wolverton's best comic book stories from the 1940s, one can make a meal of just the dialogue alone.

As if the grotesque characters, madcap pacing, convoluted plots, and dense dialogue weren’t enough, Wolverton shoves signs in virtually every empty space. For example, behind Scoop at the diner, there are signs that read:

» Clammy Counter Café Cutlets: 1 Clinker

» Coddled Collar: One Dollar

» Goons Spoons

» Blobs of Boiled Brake Bands: 1 Buck

» Scalloped Scalps: 1 Skimmer

» Big Bowl of Bicarbonate: Six Bits

And there are even more novelties and gags packed into the boxes. I’ll just mention one more, a favorite. There is a running gag throughout several of Wolverton’s humorous comic book series in which Walla Walla is mentioned. Splash panels and background signs have Walla Walla gags. Sometimes characters, including Hitler, mention Walla Walla. Just what is Walla Walla?

Walla Walla is a small town in Washington State (1940 population: 18,109; 2021: 32,793), about 200 miles east of Vancouver, Washington—where Basil Wolverton lived for 59 years. I live in the state and have been through Walla Walla myself. Grocery stores in Seattle often stock prominently labeled and delicious sweet onions from Walla Walla.

But what’s important, of course, is that Walla Walla is a hella funny name. Wolverton, like onion merchants, knew a good thing when he saw it (another Washingtonian thing I spot in the comics is soft drinks being called “pop”). The Walla Walla gags are funny enough on their own, as a single occurrence. They are much funnier when one sees them crop up over and over.

Scoop Scuttle started out as a 12-episode newspaper strip sample. When it didn’t sell after making the rounds of the syndicates, Wolverton’s agent tried the comic book market. Publisher Lev Gleason bit and Scoop scuttled into the back pages of his comics (which had previously featured early work by another screwball master, Jack Cole). Gleason then sold Scoop as a newspaper strip to a syndicate where he had connections, probably giving Wolverton whiplash.

Struggling to pay the bills, Wolverton was hardly in a position to turn down a chance at the Big Time, even if it represented a frustrating circle. The hardworking cartoonist dutifully refashioned Scoop Scuttle back into daily strips and drew 52 of these before the syndicate got cold feet and backed out of the deal before the strip saw publication. Second-tier publisher Gleason sold the strips and a last story (the Foopgoop suicide yarn) to third-tier publisher William H. Wise & Co. for a few hundred bucks, much less than the hoped-for payday. Wise ran some, but not all the strips in their Candy Comics title and the art for the unpublished dailies has been lost.

Whew.

I recount the complex publishing history of Scoop Scuttle, in abbreviated form, because it shows how close the series came to becoming a mainstream comic strip. Yes, it is that good and has deserved a lot better than its exile in the back pages of now rare and rarely-read comic books. Plus, this single example demonstrates Wolverton’s considerable talent. Few cartoonists have been able to create copious quantities of both comic book stories and comic strips, much less change a property from one format to the other and then back again. For Basil Batbrain Wolverton, it was just another day at work.

The Scoop Scuttle stories were made in the same period Wolverton arguably created his best comics. Scoop started in 1940, the same year Wolverton launched his celebrated Spacehawk series (30 stories, 1940-42, Novelty Press). Two years into Scoop’s five-year lifespan, Wolverton created his second masterpiece: Powerhouse Pepper (approximately 50 stories from 1942-48, Timely/Marvel Comics), a humorous series that has much in common with Scoop, such as the rhyming, alliterative dialogue.

To discover the joys of Scoop Scuttle, made when Basil Wolverton worked at a fever pitch of screwball brilliance and forgotten for 80 years, is like finding a lost Marx Brothers movie from their Paramount days, when they were at their unchained wildest in films like Duck Soup. In an age of recovered cultural gems made available on a regular basis, it is easy to be blasé about a new collection of weird filler humor stories pulled from obscure Golden Age comic books, but Scoop Scuttle and His Pals: The Crackpot Comics of Basil Wolverton is kind of a big deal. There is much enjoyment and some enlightenment to gain from these stories, as a more complete picture of Wolverton emerges in which it becomes clear he was one of the most gifted, inspired, and resilient screwball artists (in any medium) of his time.

For example, comparing the three phases of Scoop Scuttle, one can map out Wolverton's search to find a package for his singular style that would win him a decent income—a quest that went on well beyond the Scoop Scuttle years. The first phase exhibits a caged lion: Wolverton watered down. His art is tight, too tight. His pacing is awkward, and—even though Basil was drawing from a rich past of screwball newspaper comics—he seems reluctant to shift into high gear.

The second phase, several comic book stories, lets the lion out as blessed madness ensues. A good example (shown above) is a superb four-panel sequence of Scoop accidentally eating a man's beard, published in Captain Battle Junion #2 (Winter 1944).

Wolverton masterfully slows his pacing sometimes, for comic effect. He sits back and lets his characters act out little routines that would be at home in comedy films (and some probably are!). These visually striking sequences are similar to the wordless sequences in Milt Gross's Nize Baby Sunday comic strips (1926-29), which Gross created after working in Hollywood, writing gags for Charlie Chaplin's silent feature The Circus. The greatest use of this breakdown technique occurs in the E.C. science fiction and war comics of Harvey Kurtzman's, the cartoonist who commissioned Wolverton art for the "Life magazine" cover of MAD #11.

When Wolverton returns to the comic strip format, just two years later, the result is much more assured than the first attempt and filled with the sort of madcap pacing, background gags, and surreal humor which is characteristic of his best work.

My favorite Scoop Scuttle story, "Comic Mag Cartoonists and the Newspaper Cartoonist" (Sadowski explains the rather schematic, unzippy titles are taken from Wolverton's working notes) reflects the zig-zag formats of the series. The Daily Dally's cartoonist is fired and Scoop brings him to Colic Comics Corp., a comic book sweatshop. Upon learning there is a position open for a newspaper cartoonist, the studio cartoonists rush in a herd to apply for the job.

Mystic Moot and His Magic Snoot shows just how masterful Wolverton was in adjusting his cartooning style. Created upon request, as a side-feature for Fawcett's title featuring Ibis the Magician, the cartooning is less detailed and more reflective of the elegant, simplified look-and-feel of the art directed by C.C. Beck, who created the publisher's main property, Captain Marvel (which includes numerous screwball touches, such as a talking tiger and a mysterious arch-villain who turns out to be a tiny worm with a tiny amplifier around his neck).

"Mystic Moot and His Magic Snoot" is the perfect name for a Basil Wolverton series title. As the perverse truth would have it, the moniker was created by an editor and not Wigglewit Wolverton. Thanks to Greg Sadowski's research and writing (aided by Wolverton's son, Monte—also an artist) we now know Wolverton first submitted "Champ Van Camp and His Magic Lamp," followed by "Mystic Mose and His Magic Nose"—neither of which are anywhere near as good as what Managing Editor Will Lieberson invented. "Moot" is a nice comedic echo of "Ibis" and a funny name for a magician who speaks magic spells, being a homophone for "mute," and an echo of "moot point." The editors surely admired Wolverton for the fine quality of his work. Similarly, I am sure Wolverton appreciated help to improve his work. You might say the admiration was moot-ual.

Even though the Mystic Moot stories contain fewer funny signs and sight gags, less frenetic madcap action, and the dialogue is straight (no wordplay), the series is still quite funny. The basic structure of the series is very similar to Milt Gross's Count Screwloose newspaper comic strips (1931-35). A funny little oddball character from some foreign place traverses a large American city and fails to make sense of the absurdities he witnesses. In the Moot stories, Wolverton gets a lot of mileage—and brings in an edge—by having Moot misunderstand things, such as when he praises a prison's electric execution chair for its aesthetic qualities (were these stories really meant for the kiddies?).

Bingbang Buster, Wolverton's wacky western send-up, represents yet another tweak to his style. Back with Lev Gleason, the wacky signs return with a vengeance. Wolverton also gives himself playful nicknames, such as "Westwart", "Boulderbean", and "Wigglewit", beating Stan Lee to the trick by about 15 years.

In the Bingbang Buster stories, Wolverton continues to experiment with extended wordless comedy (it may be no accident the series uses Buster Keaton's name; Wolverton met Keaton while filming The General in Oregon). He gets a lot of mileage out Buster's horse as well, creating a charming funny animal character I wish he had used more.

The last set of stories in the collection, Jumpin' Jupiter, moves to the science-fiction genre, a familiar one for Wolverton who had written and drawn a slew of serious superhero tales starring his vengeance-driven character Spacehawk. This time, Wolverton is taffy-pulling the genre for laughs. It is fascinating to compare his bold treatment of science fiction tropes in both series, which contain some of Wolverton's most polished comic book art.

Wolverton's comic book work deserves a deeper look and further analysis. Among fans, he is celebrated for his exceptional late-period caricatures (such as the ones that graced the covers of Plop! in the 1970s) and his handful of outstanding 1950s horror/science-fiction stories, such as "The Eye of Doom". This material alone is enough to make a case for Wolverton's importance in popular culture. With the re-emergence of a generous chunk of his deliriously zany 1940-52 humorous comic book stories—thanks to Greg Sadowski—we can now have a deeper appreciation for the work of Basil Wolverton, surely one of the 20th century's greatest cartoonists.

* * *

Tall Pumey is the author of Screwball! The Cartoonists Who Made the Funnies Funny. He is currently working on the launch of Sporadic, The Magazine of Termite Archeology.