William Morgan DeBeck was a cartooning genius who made a mark in the history of the medium by renewing his creation again and again, each time with a more inventively hilarious novelty than before. Born April 16, 1890, on the South Side of Chicago, he was the son of Louis DeBeck (a French name, originally spelled DeBecque), a former newspaperman who had taken refuge in the offices of Swift and Company, and Jessie Lee Morgan, a farm girl who had worked as a school teacher. After graduating from Hyde Park High School, young DeBeck enrolled in the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, intending to become a painter in the Dutch Masters tradition, but he was selling cartoons to finance his artistic aspirations and was successful enough at it to land a job in 1910 with a weekly theatrical paper, Show World, whereupon he gave up painting.

Growing up, Billy’s talent was shaped by his admiration for the cartoons of John T. McCutcheon, the legendary editorial cartoonist at the Chicago Tribune, and Clare Briggs, who drew down-home cartoons under a rotating series of titles—When A Feller Needs A Friend, The Days of Real Sport, Ain’t It A Grand and Glorious Feelin’? Although DeBeck could produce copiously cross-hatched illustrations in the manner of Charles Dana Gilbson, most of his early newspaper work was in the fustian cartoony vein of the idols of his youth.

Like many newspaper artists of his generation, he bounced around, moving from one paper to another as better opportunities presented themselves. He left Show World within a year to take a position at the Youngstown Telegram in Ohio; after two years, he departed in late August 1912 for the Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, which he left two years later for what he imagined would be greener pastures. For the papers, DeBeck did the routine drawing assignments that fell to staff artists—sports cartoons, a few politicals, borders around photographs, spot illustrations for newsstories and columns and the like. The greener pastures he took off for, humor magazines Judge and Life in New York City, weren’t as verdant as he’d hoped, and by May 1915, he was back in Pittsburgh, teaming with a fellow named Carter to launch a newspaper feature syndicate and a mail order cartoon instruction course.

Not much green there either, so DeBeck returned to Chicago, where, in December 1915, he joined the staff of the Chicago Herald while moonlighting a comic strip, Finn an’ Haddie, for the Adams Syndicate. Finn an’ Haddie went nowhere, but DeBeck’s next comic strip concoction, Married Life, about a bickering couple named Aleck and Pauline that started December 9 at the Herald within days of his hiring, attracted the attention of press lord William Randolph Hearst, who, according to Brain Walker in his 75th anniversary reprint compilation, Barney Google & Snuffy Smith (1994) was so smitten with DeBeck’s work that he bought the Herald in order to secure the cartoonist’s services. Hearst merged the Herald with his Chicago Examiner, and DeBeck’s Married Life continued under the new masthead. DeBeck added several other cartoon features, mostly on the sports pages of the paper, taught night classes at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, and “became something of a local celebrity,” Walker said, going on to describe one of the antics that earned DeBeck his standing:

Not much green there either, so DeBeck returned to Chicago, where, in December 1915, he joined the staff of the Chicago Herald while moonlighting a comic strip, Finn an’ Haddie, for the Adams Syndicate. Finn an’ Haddie went nowhere, but DeBeck’s next comic strip concoction, Married Life, about a bickering couple named Aleck and Pauline that started December 9 at the Herald within days of his hiring, attracted the attention of press lord William Randolph Hearst, who, according to Brain Walker in his 75th anniversary reprint compilation, Barney Google & Snuffy Smith (1994) was so smitten with DeBeck’s work that he bought the Herald in order to secure the cartoonist’s services. Hearst merged the Herald with his Chicago Examiner, and DeBeck’s Married Life continued under the new masthead. DeBeck added several other cartoon features, mostly on the sports pages of the paper, taught night classes at the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, and “became something of a local celebrity,” Walker said, going on to describe one of the antics that earned DeBeck his standing:

“Legend has it that on Armistice Day, November 11, 1918, DeBeck rode a white horse through the saloons of Chicago and after his night of revelry fell asleep on the desk of Arthur Brisbane, [Hearst’s fearsome factotum of all jobs, then serving as] editor-in-chief of the Herald and Examiner. The next morning, Brisbane chased Billy out of his private office, but Billy returned shortly after, interrupting an important meeting to retrieve his socks, which were neatly tucked away in Brisbane’s dictating machine.”

DeBeck’s next notable antic was to invent another comic strip, which was launched June 17, 1919, on the sports page. Entitled Take Barney Google, For Instance, this new endeavor partook somewhat of the domestic travails that distinguished Married Life but with a difference: it concentrated on the husband’s fixation with the sporting world in defiance of his wife’s opposition. Despite all that henpecked Barney could do, the strip just limped along. Shortening the title to the name of the protagonist didn’t help much either. Then on July 17, 1922, DeBeck arranged for Barney to acquire a race horse named Spark Plug, and the sad-faced nag, most of whose anatomy was hidden underneath a moth-eaten shroud-like horse blanket, became, as Walker puts it, the Snoopy of the Roaring Twenties. Barney entered his sorry steed in a race, and DeBeck, drawing with a loose but confident line and intricately hayey shading, quickly discovered the potency of a novelty in comic strips of the day—continuity, which, at the time, almost no comic strips indulged in.

The crucial months in 1922, May 18 to December 26, when DeBeck radically altered the theme, and thereby the circulation, of his strip, are reprinted in IDW’s Barney Google, a handsomely produced 2010 volume edited and introduced by Craig Yoe. In May, the strip was a gag-a-day strip about a ne’er-do-well husband; in July, it became a humorous continuity propelled daily by comedic suspense about its protagonist’s fate as the owner of a race horse. As the strips reprinted in this book for the first time reveal, Barney fritters away his winnings on high living and the pursuit of beauteous ladies (having forgotten, apparently, that he is married). When one of them dumps him for a more wealthy sugar daddy, Barney goes back to Spark Plug and they go to Cuba for the big race in Havana. By the end of the year, he is sitting pretty financially and the love affair is between him and his horse, which circumstance no doubt did as much to endear the strip to readers as did the suspense DeBeck conjured up about the outcome of the next race or of Barney’s latest infatuation. (DeBeck depicts the outcomes of the races, but never the races themselves; he probably didn’t want to spend a lot of time drawing horses.)

Yoe’s introduction, quickly rehearsing DeBeck’s biography and the history of the strip (particularly its incarnation in the movies), is accompanied by a “scrapbook” filled with photos and newspaper clippings and includes a passing assertion, fraught with historic significance: the Spark Plug inaugural sequence was reprinted in the tenth issue (October 1922) of Comic Monthly, “the first monthly newsstand comic publication,” produced, Yoe tells us, by Embee Distributing Company of New York and featuring the reissue of such comic strips as Tillie the Toiler, Polly and Her Pals, Little Jimmy, and Barney Google.

The suspense inherent in a continuing story captivates readers, and so for most of the ensuing decade, DeBeck kept his audience on tenterhooks by entering Spark Plug in a succession of suspenseful contests, the outcomes of which were never certain (some of them, surprisingly, Spark Plug won). DeBeck milked the suspense inherent in continuity for all he could squeeze out of it: To prolong the tension, on some days the strip appeared as a sort of “editorial cartoon” in which the current suspenseful predicament was dramatized in visual metaphors and symbols, heightening the anxiety by restating its terms without bringing matters any closer to resolution.

The strip increased in readership and circulation, and it was relentlessly merchandised. In 1923, songwriter Billy Rose contributed to its notoriety with the song, “Barney Google,” which became a smash hit due, doubtless, to an irresistible refrain that referred to a conspicuous feature of Barney’s visage—“Barney Google with the goo-goo-googly eyes.”

Barney’s eyes stayed the same size for as long as he appeared in the strip, but the rest of him didn’t. When the strip started, he was as tall as his wife, but he shortly started losing altitude, and by 1921, Barney was a gnomish wart, a scrunched-down jot of his former tittle, a pipsqueak mote of a homunculus—a perfect comic runt of a character who looked as outlandishly funny as his obsessions were fanatical. Among the latter, a propensity to admire chorus girls and other beautiful manifestations of the opposing sex.

Hearst had suggested, in the strenuous manner for which he was renowned, that DeBeck put a pretty girl back in the strip, but DeBeck resisted, briefly, claiming he couldn’t draw pretty girls. As it turned out, this was one of the few things in comic stripping that DeBeck was wrong about, and when he finally relented and acquiesced to the boss’s dictum, the girl was as beautiful and voluptuous as any in the funnies.

“And then the fun began,” DeBeck recalled. Quoted by Walker, he unfolded the story. DeBeck said he was at a loss for a name for this paragon of pulchritude. “Muriel, Jane, Eliza, Annie—none of them fit,” DeBeck said. “Stymied no end,” he finally hit on a pet name instead of a proper one: Sweet Mama.

“Wow!” DeBeck went on. “That started something. Letters poured in. The readers wanted to know where her child was. How could a single gal be a mama? Was Barney the father, etc., etc.? We lost several clients. Brisbane phoned. ‘Cut out Sweet Mama,’ he demanded. ‘Go back to Spark Plug.’ But in two short weeks the expression ‘Sweet Mama’ had swept the country. Songs were written about ‘Blonde Mamas,’ ‘Red Mamas,’ and so on. Brisbane phoned again. ‘Put Sweet Mama back in the strip,’ he said—‘don’t you know when you’ve got sump‘n?’”

Thereafter, DeBeck went on, he started regaling his readers with colorful invented argot. With such linguistic stunts, the inventive cartoonist proved perfectly capable of contributing to popular culture single-handedly without Billy Rose’s help. In the strip, DeBeck coined a parade of expressions that captured the public’s fancy: in addition to sweet mama, DeBeck gestated heebie jeebies, horsefeathers, hotsy totsy, osky wow wow, and bughouse fables, to cite a few.

Somewhere amid a procession of sweet mamas, Barney’s wife (whom he had called “sweet woman” in their inaugural appearances) faded from view. Once Barney became obsessed with Spark Plug and horse racing, Mrs. Google seldom showed up. And Barney never mentioned her—for months, sometimes years. An unnamed daughter of a somewhat preschool age likewise vanished from view (she, within hours of the strip’s debut). The sweet woman would wander back into the strip every once in a great while, and on one of her return engagements, in 1928, she was married to Horseface Klotz, a friend of Barney’s to whom Barney then explained that he’d been married to her long ago. Clearly, he no longer was. Henceforth, Barney was an unapologetic bachelor. Not that he’d ever felt like apologizing for his wandering eye: he didn’t, and he even told a pretty girl on a park bench that he was a “confirmed bachelor” as early as October 20, 1919, less than six months after his debut as a henpecked sports fanaddict (sic).

As an unabashed philanderer, Barney broke one of syndicated cartooning’s most sacred taboos: comic strip husbands weren’t allowed to cheat on their wives. Nor were husbands permitted to beat their wives. Just down the page from DeBeck’s strip was George McManus’s in which Maggie regularly pelted her husband with crockery; but Jiggs wasn’t permitted to fight back. Barney, however, got away with playing around while his wife stayed home and played house.

Maybe it was because he was so short: how realistic was it to suppose that such a shrimpboat could fascinate beautiful women? And if Barney’s dalliances weren’t realistic, they couldn’t, perhaps, threaten the institution upon which all civilization was founded—marriage and the family. Or maybe Barney got away with it because he no longer had any visible children; neither did DeBeck.

Not even the storied licentiousness of the Jazz Age undermined syndicate prohibitions. But it was the Golden Age of Sport, as proclaimed by Grantland Rice, the dean of American sports writers—the age of Jack Dempsey, Man O’War, Babe Ruth, Bobby Jones, and Red Grange; the age of bathtub gin, flappers, Tin Pan Alley, cross-word puzzles, mahjong, and flag-pole sitting. And maybe the pervasive sense of play permitted players at indoor sports as well as outdoor sports. DeBeck himself was an avid sports enthusiast. He regularly went to prize fights, race tracks and baseball stadiums. Later, he became a dedicate golfer. His was “a man’s world,” as Walker puts it, and Barney Google appealed to just that crowd. “Barney was the Everyman of the Jazz Age. ... His adventures were the male fantasies of his loyal readers. DeBeck’s creation is a reflection of their hopes, dreams and failures.” And so Barney got away with it.

DeBeck embodied some of those male fantasies (no failures) as well as the general frenetic ambience of the age. He was, seemingly, in constant motion, showing up at events in San Francisco, then Seattle, then Washington, D.C. He hobnobbed with politicians, star athletes, actors, and authors. Newspapers recorded in pictures and prose his peripatetic comings and goings. And how could he be a wandering playboy and still produce a daily comic strip? Luckily, he was a fast worker. He might evade his deadline responsibilities for days at a time, but then he’d sit down at the drawing board and crunch out two weeks of dailies and a couple Sundays in a single non-stop sixteen-hour stretch. After blocking out a strip with rough pencil sketches of the characters to show their positions, he went directly to pen and ink, drawing “straight ahead”—that is, without knowing much in advance where, exactly he was going with a particular strip or storyline. He always claimed the last thing he drew in any strip were the dots in Barney Google’s goo-goo-googly eyes. Putting a period to each release, we might say.

In marriage, DeBeck was similarly capricious: he married three times, twice, in succession, to the same woman. But his last marriage, in 1927 to Mary Louise Dunne, settled him down. Somewhat. They moved to Paris and lived there for two years, DeBeck mailing his drawings regularly to King Features in New York.

The circulation of Barney Google had begun to slip by 1934, and the resourceful DeBeck decided to change the direction of the strip, shifting its locale from the city and the race track to the backwoods of Appalachia, joining numerous other popular entertainments of the thirties in acquainting a mainstream American audience with hill country culture. What prompted Americans’ apparently sudden interest in hillbillies is open to speculation. My guess is that it stemmed from radio broadcasts, since the mid-1920s, of country music in the weekly “National Barn Dance” originating in Chicago (1924) and “Grand Olde Opry” from Nashville (1925). As the country’s addiction to radio grew (particularly during the Depression when the appliance offered free entertainment), so did the popularity of country music—and an interest in the place where country music was presumed to originate, Appalachian hill country. DeBeck caught on by autumn 1934; Al Capp had preceded him that summer with Li’l Abner.

The circulation of Barney Google had begun to slip by 1934, and the resourceful DeBeck decided to change the direction of the strip, shifting its locale from the city and the race track to the backwoods of Appalachia, joining numerous other popular entertainments of the thirties in acquainting a mainstream American audience with hill country culture. What prompted Americans’ apparently sudden interest in hillbillies is open to speculation. My guess is that it stemmed from radio broadcasts, since the mid-1920s, of country music in the weekly “National Barn Dance” originating in Chicago (1924) and “Grand Olde Opry” from Nashville (1925). As the country’s addiction to radio grew (particularly during the Depression when the appliance offered free entertainment), so did the popularity of country music—and an interest in the place where country music was presumed to originate, Appalachian hill country. DeBeck caught on by autumn 1934; Al Capp had preceded him that summer with Li’l Abner.

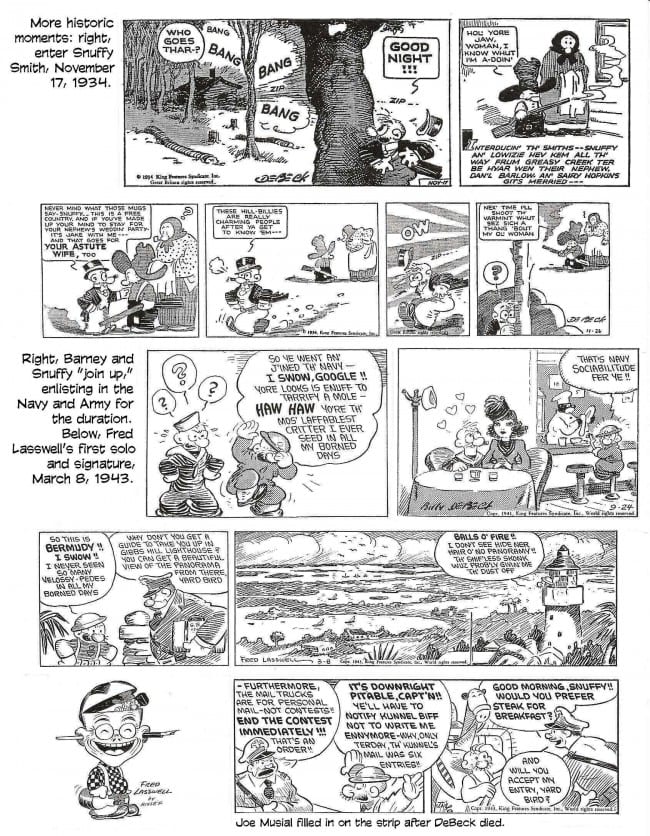

In the early fall that year, Barney Google inherits property in the mountains of North Carolina, and when he journeys there to inspect his estate, he encounters on November 17 a cantankerous hillbilly named Snuffy Smith and his wife Loweezy and an ensemble of picturesque characters. After Snuffy’s debut, most of DeBeck’s stories were set in an imaginary Appalachian community called Hootin’ Holler.

Although the strip was entirely fictional, DeBeck took pains to give his work an authentic foundation. According to comics scholar M. Thomas Inge, “in preparing for the new episodes, DeBeck traveled through the mountains of Virginia and Kentucky, talked to the natives, made numerous sketches, and read everything he could lay hands on that treated mountaineer life.” DeBeck collected books on the subject, building an impressive library of the literature and lore of Appalachia. But the help he had in refining the lore he collected came from a 17-year-old kid he’d found in a toilet.

Fred Laswell Jr. was born on July 25, 1916, in Kennett, Missouri, son of Fred Lasswell, movie theater owner and farmer, and Nellie Forence Waldridge. Fred, Sr. was in the U.S. Navy when his son was born, having sold his theater in Campbell, Missouri, to enlist immediately upon the U.S. entrance into World War I in April 1916. After the War, he moved his family to Gainesville, Florida, where he bought a ten-acre chicken farm. The farm supported a horse, a wagon, a plow, a cow, a dog, a cat, and 2,000 white leghorn chickens. But no electricity, telephone, radio, hot or cold running water. “We had an outhouse with a croker sack hanging where the door ought to be,” Lasswell remembered. “In some parts of the country, a croker sack is called a gunny sack.”

He would remember his rural roots all his life. “I remember sitting on our front porch at twilight time in a squeaky old rocking chair,” Lasswell wrote once. “Way off in the distance, you could hear hound dawgs howlin’ and yappin’ like they had just treed a big ol’ fat ’coon. And I’ll never forget the mournful cry of the whippoorwills. And you could smell a pine stump smoldering ’way off somewhere. Once in a while, if you listened very carefully, you could hear the chatter of crickets and the frogs croaking in the creek. The world shore was a purty place in them days.”

But in 1926, the Lasswell family became city dwellers. They moved to Tampa, Florida, where young Fred enrolled in Seminole Heights Elementary School. Starting at age twelve, he drew cartoons and comic strips for his school newspapers. Through high school, he earned money with a Tampa Daily Times paper route and by hawking the rival Tampa Morning Tribune on the streets in Ybor City, which, at the time, was the venue of much of Tampa’s nightlife, including saloons, gambling halls, and brothels—Tampa’s “recreational area,” as Lasswell called it in later years: “In a thirty-square-block area, there were a whole lot of small houses side by side, where young ladies lived. And, since it was hard times, four or five of them would share the same house.”

Fred quit school just before graduating and went to work part-time in the art and engraving department of the Tampa Daily Times for awhile, freelancing simultaneously, then found a job in an ad agency. “Space was at a premium at the agency, so I wound up working in the men’s room,” he said. “I sat there on the toilet seat, with the lid down and a drawing board on my lap.”

He was perched right there in late spring 1934 when he got a phone call from Billy DeBeck. In those days, DeBeck wintered at St. Petersburg, and he was golfing near Tampa with fellow cartoonist Frank Willard (Moon Mullins), baseball greats Paul and Dizzy Dean, and sports writer Granny Rice when he saw a poster that Fred had lettered. He wanted a letterer for Barney Google, and he soon hired Fred. When DeBeck went back to New York, Fred went with him. When DeBeck and his wife rented a home in Great Neck, Long Island, Fred moved in with them. “Wherever they moved, I lived with them,” he said. And they lived in a lot of places over the next few years: Great Neck, Kings Point, Port Chester, Lake Placid, and St. Petersburg.

DeBeck undertook Fred’s education. He recommended books for him to read. And he directed the youth to copy accomplished pen-and-ink artists—Charles Dana Gibson, Phil May, and others—including his own work in the comic strip, which he made Fred copy, line for line. And Lasswell also attended Art Students’ League in New York and the Phoenix Art Institute.

Snuffy Smith’s Hootin’ Holler could have been Lasswell Land: Lasswell was “country.” And he undoubtedly helped DeBeck to conjure up the aura of the new hillbilly locale. Once DeBeck moved the locale of the strip to the backwoods, he indulged his fascination with language to imbue his creation with colorful expressions that reflected the lingo of the hills. Lasswell reported that one of his first tasks involved assisting his boss in the research. DeBeck went through books about the hill folk and blue-pencilled words and phrases; then Lasswell entered all of these into a “log book,” which DeBeck later consulted for ideas and vocabulary. The two most heavily annotated authors, Inge notes, were Mary Noailes Murphree and George Washington Harris. And in the latter’s Sut Lovingood’s Yarns, Inge says, “there isn’t a page not heavily annotated.” DeBeck borrowed copiously from Harris for the dialect spellings of such words as “hit” (for “it”), “hyar” (“here”), “mought” (“might”), “orter” (“ought to”), “propitty” (“property”), and so on.

Aided, doubtless, by his country-boy assistant, DeBeck also concocted entirely new expressions that had the ring of Appalachian locutions—daider’n a door-knob, time’s a-wastin’, a leetle tetched in the haid, shif’less skonk, bodacious idjit, ef that don’t take th’ rag off’n th’ bush, and others. And many of these (like “balls o’fire” and “jughaid”) joined “heebie jeebies” and “Sweet Mama” in the popular slang of the day.

Lasswell started contributing gags and other ideas to the strip almost at once, but it wasn’t until 1941 that DeBeck gave him a chance to solo. Lasswell wrote and drew a six-week sequence (February-March) in which 30,000 soldiers go to Hootin’ Holler for practice maneuvers and encounter hostile hillbillies, who have mistaken the uniformed legions for “revenooers” bent on destroying the local distilling business.

Despite the authenticity of the strip’s language, the stories and situations partook of the stereotypical portrayals of mountain men and women in the literature about the region. Mountain men carried rifles wherever they went, and Snuffy was always willing and able to “bounce a passel of rifle balls off’n punkin haids” of miscreants in his path. Laziness, chicken thievery, stills of corn whiskey, ignorance, illiteracy, belief in ghosts and wood goblins and other supernatural creatures, feuding families, weddings of the offspring of feuding families, and stubborn individuality are frequent motifs in DeBeck’s Snuffy Smith tales. Snuffy himself is the epitome of self-centered, opinionated indolence. But Snuffy became so popular with readers that by the end of the 1930s, he was given equal billing with the eponymous star when the strip was re-titled Barney Google and Snuffy Smith. The hillbilly years of the strip inspired two motion pictures and numerous animated cartoons.

During World War II, both Barney and Snuffy “joined up,” as the saying goes. Snuffy first. After days of rejection (he was too short and had no teeth), he finally got himself into uniform in the Army on November 13, 1940—well before the U.S. had even entered the hostilities. But the draft had been introduced in September that year, so Snuffy’s enthusiasm was in step with the times. (He was motivated, we suspect, more by the promise of “thutty dulers a month” than by rampant patriotism, but we’ll leave that aside for now.) Barney went into the Navy but not until a year later, September 1941. Again, before we were actually at war. The strip was popular with service personnel because its protagonists were both in the military, but Snuffy was on stage more than Barney and popularized the expression “yardbird” for a kind of military camp loafer.

(continued)