Here's a piece of vintage Harv from 1995: a profile of the late Betty Swords.

Humor is a big joke on us all. It’s one huge paradox. While it seems unconditionally benevolent, stimulating laughter and good feeling, it is often cruel, destructive, and manipulative.

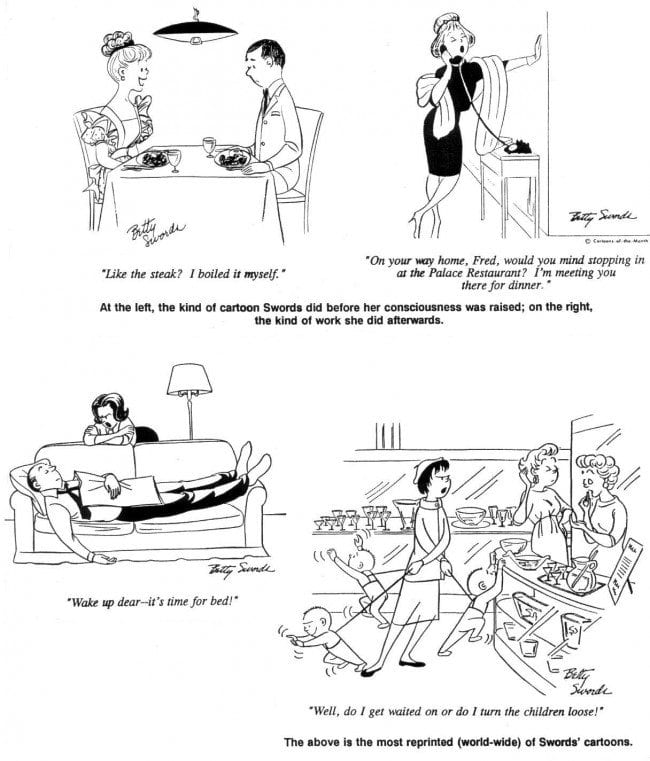

So says Betty Swords. And she should know. For over twenty-five years, starting in 1955, she was a professional humorist. She sold her cartoons to the major magazine markets, including Saturday Evening Post, Redbook, Good Housekeeping, Ladies Home Journal, Changing Times. She also produced a considerable quantity of humorous writing for such publications as McCall’s, Modern Maturity, Christian Science Monitor, and others. And beginning in 1976, Swords taught college courses in the power of humor and lectured widely on the subject. (The substance of her lectures she has incorporated into a book project, Humor Power; excerpts from the precis for the book appear at the end of this report.)

Swords discovered the hostile side of humor after she’d been cartooning for a dozen years or so. “I was reading a book of comic one-liners,” she reported, “—The Encyclopedia of Humor by Joey Adams—when I became aware of a growing discomfort. People usually skim these books, but I had to read them thoroughly because I reviewed them for the Denver Post. I was growing punchy from the aptly-named punchlines. And then I realized that the punching bag was always a woman. “Marriage is seen as bad,” she went on, recollecting the experience as we talked on the patio in back of her Denver home in June 1995. And she cited examples of one-liners to prove her point:

Married life is great—it’s my wife I can’t stand.

He was unlucky in both his marriages—his first wife left him. And his second one won’t.

A bachelor’s last words—I do.

“Marriage is seen as horrible because it meant that the man had lost his freedom,” she continued. “Everything about marriage was very bad for men. I kept going through the books, looking. Husbands were bachelors who had run out of luck. Then I checked cartoons. Cartoonists usually have their studios at home, and I thought they’d be more domesticated than, say, night club comedians with their one-liners. And I found that in one way cartoonists were worse: I saw how hideously ugly they made the battle-axe wife. Women were either babes or battle-axes. As babes, they were always trying to trick a man into marriage, after which they got bigger and became battle-axes.

“All the jokes were not only against marriage,” Swords went on, “they were against women as well: the fall guy was a gal.”

More incriminating one-liners:

A woman’s brain is divided into two parts—dollars and cents.

Women have a tough life. They have to cook and clean and scrub. That’s hard to do without getting out of bed.

“Women were dumb about money, dumb about driving, dumb about anything that happened in the real world,” Swords said. “And that began my trip into feminism. I began to see how humor treated women. Dumb, dumb, dumb. Humor did it to blacks, too; they were dumb. Did it to Jews—not dumb, but sly; not to be trusted. The Irish at one time were the victims of humor. The Polish. The power of the stereotype. When you made them the object of humor, you could make them lose their humanity and become objects of ridicule, and you could even kill them with impunity.”

Suddenly, Swords said, she realized why there were so few women cartoonists. “Actually, it’s probably easier for a woman to become a doctor or lawyer than a cartoonist,” she said. “It’s men who dominate the humor field, especially in cartoons.”

Women cartoonists are discriminated against because of their ideas. “Women don’t make jokes,” she said, “because they are the joke.” What’s funny to a woman doesn’t appeal to male editors, who tend to want women in the jokes to be the butt of the humor; and women are likely to be uncomfortable to be always in that roll.

All at once, her “rather Pollyana view of humor as a kindly contemplation of life’s incongruities” (quoting Stephen Leacock) changed: she saw humor’s tremendous power “to kill as well as to amuse. Humor commits countless little murders of its victims’ self esteem. I saw that too often men used humor as a weapon against the Others of society, and it was women who marched at the head of this Hit Parade. And since each of us marches to a different drummer, we all join the humor hit parade at some time.”

Swords’ journey of discovery began in an antebellum hotel in a little town in Mississippi in the early 1940s. She grew up in Oakland, California, and earned her bachelor of fine arts degree at the University of California at Berkeley. She did graduate work across the Bay at the San Francisco Academy of Advertising Art.

“I specialized in fashion illustration,” Swords told me. “What I had planned to do—from the time I was four—I wanted to draw the most beautiful paper dolls. And as I grew older, I was constantly drawing paper dolls, designing clothes for them and so forth. In high school I studied costume design, and in college they had something called Household Art, which was hardly very good for cartooning. When I graduated from college, the only real place for costume designing was New York, and the designers were in New York—and they were all men anyhow—and it just seemed like not a very good idea, so I went to that school in San Francisco and did fashion illustration mainly.”

I asked: “Was this an acceptable career for a woman at that time?”

“Yes,” she said. “Fashion illustration for women’s clothes, in particular. Women were not supposed to be able to draw men. And we had one student who did a wonderful job doing men’s fashion, and she ended up with a job at a men’s store. But I didn’t do any fashion illustration until after we got married.”

Swords married a doodlebug. “Leonard’s a geophysicist,” she explained. “Oil exploration. We moved a lot. For six years, we averaged a move every two months. We were in California the first year. But after that, it was all over. Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi.”

For most of that six years, World War II was raging, and the home front was plagued with shortages—“certainly in housing,” Swords said. “Nearly half the time we lived in auto courts; motels didn’t exist out in the boonies where they usually find oil. I tried freelance fashion illustration while we were in Sacramento with great success. I got work right away in three stores—and after three weeks, we were transferred. It was even worse in two other places: we were transferred before I started work. Frustrating! Fashion work requires a good-sized town, and staying put, neither of which is common to the doodlebug (oil exploration) life. I was stuck with painting scenes—when there was any scenery. And then we arrived at Stafford Springs, in the wilds of Mississippi—population, two, I think,” Swords said with a grin.

“It was a health spa, hot springs. We were there for a week’s work, which lasted almost a month because it rained and poured and thundered every day, and when that happened, the roads became impassable. And the electricity went off. The refrigeration went off, and no water! We carried our little jugs from the wells at the bottom of the road up to our hotel room to flush the toilet or to wash. Anyhow—there was this book in the hotel lobby, a beat-up copy of Writer’s Yearbook. And in it was an article about cartooning, and it said, ‘Now that so many men are in the service, women are welcome in the cartooning business.’ Not only that but it observed that cartooning was the only form of commercial art that can be done by mail—from anywhere!

“Both of those things hit me,” she continued. “If anybody was any place and every place, it was me. I began drawing. I always loved humor, and I loved drawing people. In fact, I used to read the Saturday Evening Post from the back and make scrapbooks of the cartoons and of ‘Postscripts’ [the jokes and cartoons page]. So eventually, when I got into the Post and then into ‘Postscripts,’ it was quite exciting. But it was a long ‘eventually’ because I hadn’t met a cartoonist, I hadn’t met an editor, so I wasn’t sure how to go about it; I just read what was in the Writer’s Yearbook about sending cartoons to different markets—which I did—in pencil! I sent just the pencil rough. Later I learned that I should have enclosed a finished inked drawing with the roughs. And of course I sent them to all the top markets to start with. Gurney Williams at Collier’s had held a couple of mine, but I never sold a one. There or anywhere. And we kept moving. I quit cartooning after awhile. The backs of my cartoons were just covered with different addresses. The postage was adding up. And the mail took forever to catch up with us.”

She quit doing cartoons but she never stopped thinking of cartoon ideas, and when she and her husband finally settled in Midland, Texas, she joined a writer’s group. And then she took up gag writing.

“One of the first places I tried was Dennis the Menace [which began in 1951],” Swords said. “I had two boys, one older than Dennis, one younger. So I had some Dennis ideas. And at one of our writer’s group meetings, we had paper napkins with Dennis cartoons on them. That’s what prompted me to submit to Hank Ketcham. I didn’t write first and ask; I just sent about eight gags at the same time as I asked if he wanted any. And when I met him a few years later, he said he rarely ever bought gags that way. He had a couple regular gag writers that he used. But for some reason, the ones I sent hit him. And I worked for him for some time.”

She also furnished gags to Dave Gerard, Martha Blanchard, Irvin Caplin, Morrie Brickman, and others. Eventually, she heard about New York Cartoon News, a little newsletter for cartoonists and gag writers. She corresponded with the editor, Don Ulsh, who, when he learned she had a background in art, urged her to draw up her own gags.

“If you ask, who inspired me,” Swords said, “the answer is, No one. There weren’t that many women. There weren’t that many cartoonists I could relate to that way. Plus the fact that I grew up with the notion that copying was terrible. I wish I hadn’t. I would have learned a lot faster. What I did was to do a page of facial expressions that I copied from different cartoonists. I’d make pages of action, copying from action pictures—stick drawings. All this for my education.”

I said: “Traditionally, that’s exactly the way most cartoonists learning cartooning—by copying other cartoonists.”

“I think that’s fine,” she said. “Now. That’s the way they should learn. I saved cartoons and kept them for scrap when they illustrated things I wanted to draw. Baseball. The theater.” Swords agonized over her cartoons, and much of her suffering derived entirely from not knowing cartoonists or meeting editors and finding out what could be done and what couldn’t be done. In retrospect, however, she sees this circumstance as a mixed blessing. “I was unlucky,” she said, “to be starting cartooning away from New York or any major city where I might have found help handy—responses and advice, that sort of thing. But I was also lucky—lucky that I didn’t start in the New York area because it would have been easy to blame a beginner’s problems on being a woman in a man’s field. When I finally got to New York, I met about sixty cartoonists; only one was a woman. But it was too late to quit then since I’d already started selling to the Saturday Evening Post.”

In 1954, she acquired an agent to sell her cartoons—Alice Heuman. “Agents certainly aren’t necessary,” Swords said, “nor is it usually possible to get an agent until you are selling, but I seemed to need a lot of crutches, and Alice’s biggest advantage to me was that there was someone waiting every week for a batch of cartoons from me. Editors at magazines couldn’t care less about whether I produce or not, and it was easy to get too busy to get out a weekly batch—until I got an agent, who was always waiting.

“Another reason I wanted an agent was to save time,” she continued. “That summer, one batch of mine had been gone six months to only two publications. The seasonal gags were quickly out-dated. An agent can visit most major markets in a day.” Heuman sold Swords’ first cartoon within a few months to King Features’ “Laugh-A-Day.” Shortly after that, the Saturday Evening Post started buying. She knew she had arrived, she said, when she started all at once to get letters from gag writers, offering to sell her ideas, most of which were heavy on the battle-axe wives with rolling pins—“an old and sturdy stereotype,” Swords said.

Soon she was appearing in many other magazines. Eventually, she made it into The New Yorker, too--in a noted series of ads about carpet: “A Title on the Door Rates a Bigelow on the Floor.” Hank Ketcham urged her to go to New York to meet editors and others in the business, and later that year, she did. Ketcham gave her other sound advice, too, Swords said: “He recommended taking a ream of paper, drawing 500 cartoons—and then start sending them out.” He also suggested that she regularly attend community theater. Stage productions provide good examples of how to compose a scene in a single panel cartoon. When Swords went to New York, Heuman took her around and introduced her to cartoonists and to editors. She stayed five days, and she made the rounds on Look Day, Wednesday.

“I met Gurney Williams,” she recalled. “And it was strange. After all the time I’d been sending things to him since the forties, he was strangely stand-offish. He wasn’t helpful, wasn’t welcoming. I think now that he was just shy, but then he scared me. Later, he found out through a friend of mine who was selling humor pieces to him, and he wrote me a note, saying, ‘Kay says I scare you.’ And what he told her was that he liked my work but my men were too young. I thought that Hank Ketcham had the right idea: that the father of a small boy should be young. And most of the cartoons in magazines then had fathers and mothers who looked more like grandparents.”

“Not realistic at all,” I said.

“No,” she said. “And the majority of my cartoons were domestic cartoons, dealing with the family—momma, poppa, and the kids. The main difference between young persons and old you can see in the neck: older people’s heads come right down to their shoulders; younger people have necks.”

With a husband and two young children under foot, Swords quickly realized that she needed the discipline of a regular daily regimen in order to produce enough cartoons to keep her agent occupied. Her routine is based upon a simple rule: Never do housework while the children are at school. She began the practice when her youngest son entered nursery school. “The moment he’d leave the house,” she said, “I’d take my coffee to the work table and get busy.”

She spent the morning writing, then read a little, then worked on cartoons in the afternoon. Household chores began after school. “Housework doesn’t take a brain,” she said. “I could do that and talk to my children at the same time.”

Her routine didn’t leave much time for fancy cooking on a daily basis, but Swords made up for it with a “cook in” on most Saturdays. (Swords added “most” to the sentence while this piece was in its penultimate state, saying, “I sound so darned organized, and I wasn’t that good at it!”) On Saturday, she’d make six times an average family favorite recipe and freeze what wasn’t eaten that night. Over a period of weekends, she accumulated a variety of frozen favorite meals that she’d thaw out on weekdays. It was a maneuver that made great sense to her: “You go through all the work and make enough for only one meal, and—whoosh!—it’s all gone at once. My way, there’s something left for all that effort.”

Even with the discipline of her workday, Swords’ output was relatively small. She spent as much as two hours drawing and inking a cartoon; her weekly batches were 5-7 cartoons. She once described her method as follows:

First I draw on a tracing pad, a difficult action shot may find one figure redrawn with additional tracing papers; a complicated background may be drawn on another sheet of tracing paper placed over the first. All the principles of good art are basic to cartooning, and most cartoonists are wonderful artists. In cartoons, the artist must be selective. The sketches may be detailed, but there is an art in selecting which details to draw.

In transferring the sketch via light table to good quality typing paper, I often push the people closer together. One of my greatest faults has always been scattering the people too far apart, hating to overlap them—which is one reason I still work with tracing paper: it enables me to correct this tendency. I transfer in pencil since I can’t do a good job this way in ink, and then I do my inking with a No. 1 Winsor Newton brush. I do not take one cartoon through from start to finish but always work on the week’s batch at once, first in pencil, then transferring, and finally inking, the inking being done in the morning when I am freshest.

Eventually, Swords abandoned the brush. “Recently, I’ve been using a Flair pen—terrible if you want to use water. I loved the brush—thick and thin. But when it’s reduced a lot, you lose the thin. And when you haven’t been working a lot, doing it every day, you lose that perfect touch of thick and thin. So the Flair pen is fine. I like it.”

Shortly after selling her first cartoons, Swords started selling humorous text pieces, too. Some ideas were simply too complex to be adequately conveyed by cartoons. “My pieces were like those Erma Bombeck does—or, before her, Jean Kerr,” Swords said. “A number of them were sold to the Christian Science Monitor and to the Denver Post Sunday magazine, Empire. The nice thing about doing short humor pieces is that I could illustrate them, too. Sometimes I got more money from the illustrations for my own articles than I did for the writing.”

I asked: “To what extent were you made conscious of the fact that as a woman you were either doing something you shouldn’t do or that you were unusual because you were doing it?”

“Constantly,” she said. “Still. One of the issues of Cartoonist PROfiles that Jud Hurd sent me has an article in which the writer says that only one or two percent of the cartoonists are women.” I said, “I think of women cartoonists in the twenties—like Alice Harvey, for example, who was printed in Life, and Judge and even The New Yorker—”

”And the one with the dog.”

“Oh, yes—Edwina Dumm,” I said. “Who, by the way, was the first female political cartoonist.” Swords corrected me: “No, I don’t believe so. I have a book put out by the University of New Mexico Press by Alice Sheppard. Called Cartooning for Suffrage, it traces the political cartooning done by women way back in the 1800s. In abolitionist newspapers, for example. Edwina may have been the first woman political cartoonist in a regular paper.”

“Yes,” I agreed. “Her paper was a weekly, the Monitor, in Columbus, Ohio, near where she grew up. And then she went on to do the comic strip, Cap Stubbs and Tippie. And the amazing thing was that she did her political cartooning even before women could vote—before 1920. But I’m thinking of people like Alice Harvey, Ethel Hays, Mary Petty, Dorothy McKay—who appeared in Esquire magazine from the first issue on, I think. And Mary Petty who appeared there regularly. They were drawing for a male audience, even.” Swords nodded. “Most of them employed the male stereotype. And who was the one who did her pictures in color?”

“Barbara Shermund,” I said.

“Yes, yes. Hers were gold-diggers, dames—amateur prostitutes.”

“But these women cartoonists were making a living, even in a male-dominated field,” I said. “They were being published.”

“Yes, that’s true,” she said. Then she smiled. “At one time, I sold general cartoons to some of the men’s magazines, the girlies—until I went into a newsstand one day and looked at one.”

I laughed: “And then you decided you didn’t want to be there!”

She laughed, too: “I said this is not for me.”

(Continued)