The gap in perceived cultural value between conceptual art and gag cartoons cannot be wider. The practices exist at opposite polarities of artistic expression. A conceptual art practice may be entirely immaterial, or manifest as found objects, performances, written propositions, or art objects that critique what it means to be an art object. A gag is nearly always a rectangle with pictures inside it and text beneath it. The image and the text combined make a joke. The one and only purpose of the gag: a laugh. But within this format there are infinite varieties, and the self-reflexivity so characteristic of conceptual art is often found therein.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, underground cartoonist Mark Newgarden and fine artist Richard Prince both embarked on investigations into the idea of humor and its representation in gag cartoons while presumably remaining oblivious to one another’s work. A comparison of the two is useful in showing the shared concerns and telling disparities between the approaches of illustrators and fine artists.

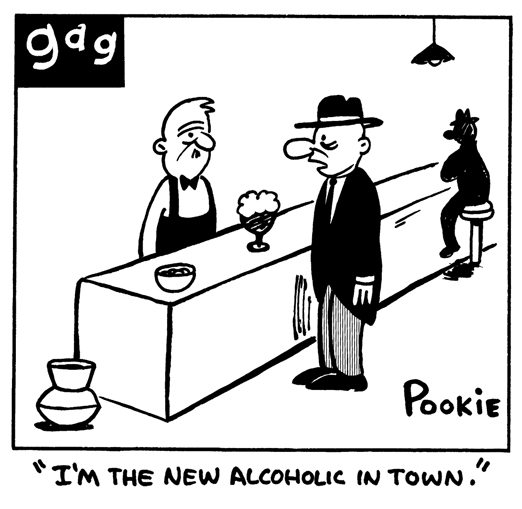

The humor in Newgarden's gag cartoons is contingent on his audience's familiarity with the tropes and clichés of gag cartoons. Anyone familiar with the bar scene in a gag panel is expecting its attendant drunkards to say something pithy, a little sad, but witty and a bit more honest than we can muster in our lives of relative sobriety. What we get in "Gag" is "I'm the new alcoholic in town." If it was "I'm the new drunk in town" you'd get the idea of a drunk as a vocation, the legitimization of a continuous and abject state of inebriation. Boom! Joke complete. Traditionally, however, the word "alcoholic" is too honest to be funny, as it articulates a very serious problem --a disease, even. The gag is completely transparent about its cruelty and pathos, but the cartoon is drawn in an extremely broad, simplistic style that lends the whole sad milieu an overpowering goofiness, which serves to turn the whole thing around and make the disarmingly honest "alcoholic" actually funny.

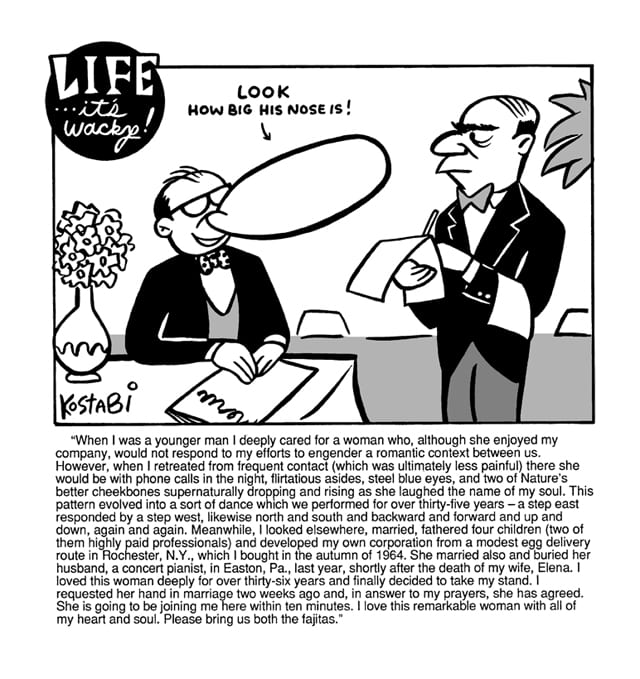

In the black-tie restaurant scene of “Life ...It’s Wacky!” the customer’s nose is three times the size of his head. Just to drive home the fact of the enormity of his organ, the words “LOOK HOW BIG HIS NOSE IS!” accompany an arrow pointing at his nose. You are prepared for some gastronomical punch line, but below the picture you find an incredibly dense and surprisingly affecting monologue about the peaks and valleys in the relationship between the customer and the woman he is waiting for. The story ends with “I loved this woman deeply for over thirty-six years and finally decided to take my stand. I requested her hand in marriage and in answer to my prayers she has agreed. She is going to be joining me here in ten minutes. We’ll both have the fajitas.”

Newgarden is pointing to a condition where most of us are more familiar with cartoons of people making gaffes in fancy restaurants and drunks saying outrageous or sad things in bars then we may be with actual fancy restaurants or drunks in bars. The tireless repetition of the same scenarios in countless syndicated cartoons and magazine gags create a situation where the conventions themselves become the source of humor. It is the conventions, and not the situations they are based on, that we are familiar with.

Richard Prince works with a similar technique of disrupting what is expected from a punch line in his joke paintings. These feature appropriated cartoons taken from publications like The New Yorker and Playboy, but with texts that are jokes from joke-books. They are self-contained one-liners that require no pictures to set them up, so that the picture goes “unexplained” or inarticulate and the text is divorced from the imagery what we expect it to enhance. On the one hand, both elements become redundant or pointless. On the other, the vieewr is trained to make a connection between text and image, and this tendency is exploited in the paintings. Our brains are being temporarily tricked into bogus meaning-making.

Whereas Newgarden’s humor manifests as functional jokes about how jokes are created, Prince's jokes are simply defused and deconstructed, and his humor remains more withholding. The jokes he appropriates are unfunny borscht-belt groaners. Gags like a woman catching her husband in his office with his secretary on his lap become vaguely disturbing and sad without the levity of an appropriate zinger attached. According to Nancy Spektor, in her essay for his 2008 recent retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum, this is Prince “bring[ing] to the surface the hostility, fear, and shame fueling much American humor.” (Spektor, p.37)

In the conceptual art mindset, the humor must be obfuscated and neutralized before the nastiness beneath it can be revealed. I would argue as much shame, fear, and hostility are evident and made obvious in Newgarden's work, and with a functional sense of humor intact.

The comedic motivation behind pairing tired jokes with tired imagery on a large canvas is blatantly nihilistic. The failure of the jokes and gags are built in to the composition of the work, relegating humor into a subject rather than a tool for communication. These neutered sex cartoons are incapable of triggering any honest laughter, and thereby reinforce the objecthood of the painting and its status as painting as painting --art as art-- thereby keeping it firmly entrenched in a tradition of the avant-garde and safe from being confused with entertainment.

Iconic in this tradition of the avant-garde, and perhaps the most celebrated work which points to the disparity of language, image, and reality is Magritte's The Treason of Images (This is not a Pipe) from 1929. The image is of a pipe, and the text asserts "Ceci n'est pas une pipe" ("This is not a pipe"). The text re-asserts the phenomenological fact of the painting rather than the illusion the painting is supposedly intended to create.

The immediate precedent for Prince's approach was set by John Baldessari. Baldessari's paintings of the '60's and '70's can be seen essentially as pranks. A familiarity with the text-image relationships established by the surrealists and Dadaists and the anti-painting position of conceptualists like Joseph Kosuth are not necessary to understand why these paintings are funny, but they help to illuminate why they are art with a capital A.

Baldessari's text-on-canvas paintings poke fun at our expectations and valuations of paintings, ultimately in order to perform the double duty of ideologically destroying painting and cashing in on collectors' and museums' love of collecting paintings. Baldessari's texts refer to the hypothetical content they are intended to embody, the conceptual ground they are supposed to be breaking, and they sometimes appear to quote how-to books and textbooks on the nature of art and painting itself. These paintings assert that there is no inherent content in painting. It is all what we learn, through language and philosophy, that we imbue paintings with, and project onto them.

It’s possible to see these paintings as cartoons without pictures. The object of the stretched canvas is the “gag”, and the text is the caption. That the caption is on top of the gag complicates the joke, but this situation opens up the possibility that these are not paintings-as-paintings but paintings-as-representations-of-paintings; paintings that embody the absurdity of the ideals of purity in art.

If Baldessari made gags masquerading as conceptual art, Newgarden certainly created conceptual art masquerading as gags.

“IMAGINE THE FUNNIEST PICTURE IN THE WORLD: IMAGINE THE SADDEST TRUTH” or “IMAGINE A DRAWING OF DENNIS THE MENACE/ IMAGINE A SENTENCE OF SAMUEL BECKETT'S” These gags dispense with drawing and simply rely on the graphic presentation of language to convey an idea.

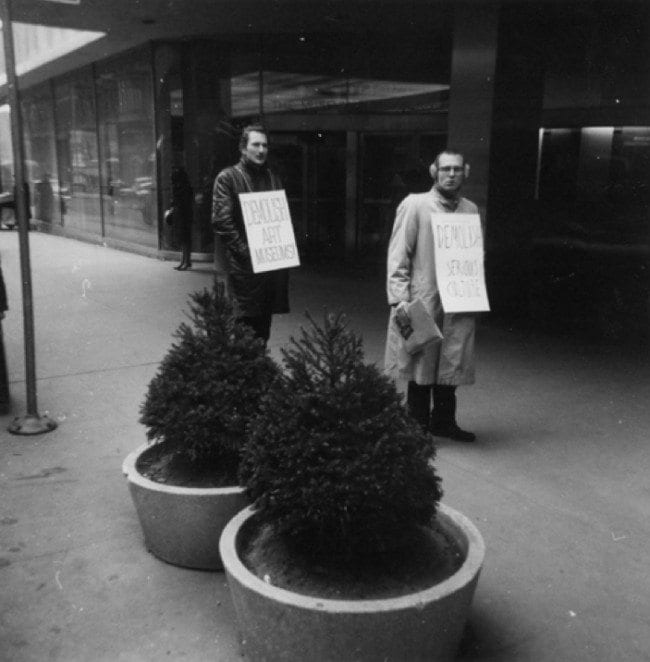

These text gags evoke the print and billboard "Imagine" campaign launched by John Lennon and Fluxus artist Yoko Ono. I am also tempted to link these works with the idea of "concept art" proposed by fellow Fluxus artist and experimental musician Henry Flynt in 1963. This idea, a prototype for conceptual art as we know it, is described by Flynt as "a kind of art of which the material is language". (Incidentally, Flynt also also called for the destruction of "Serious Culture" and protested against art institutions such as the Museum of Modern Art, as pictured below.)

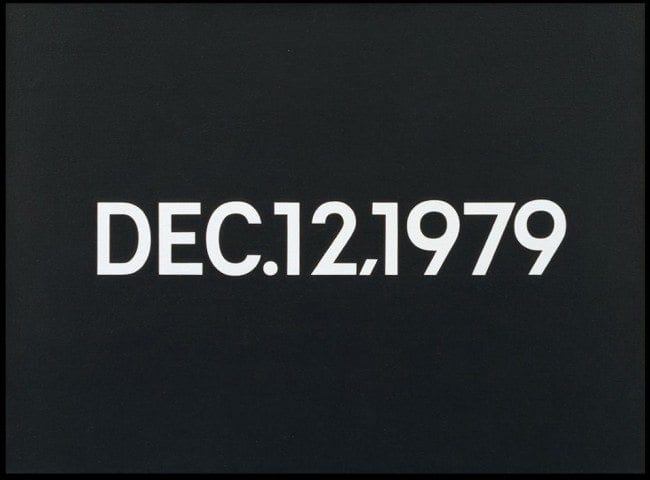

It could be argued that “NOTHING FUNNY THIS WEEK”, as received in a comic strip space in a free weekly newspaper, could actually have a jarring impact that would make one aware of the phenomenological presence of the space of a cartoon strip; the location of where the “funny” is supposed to be, made more present by its denial and absence. The white-on-black text evoking the ultimate-deadpan of On Kawara, who paints the day’s date on a canvas and packages that canvas in a box with the day’s New York Times, over and over again every single day.

I asked Newgarden if he had any major conceptualist influences. He told me “I grew up in NYC in the 60s & 70s, went to art school in the early 80s so I’m not exactly oblivious to the existence of conceptual art,” however “to me NOTHING FUNNY THIS WEEK has more in common with [Tex] Avery’s TECHNICOLOR ENDS HERE or [Ernie] Bushmiller’s THIS IS A PICTURE OF NANCY IN A HEAVY SNOWSTORM”.

Although it is this comic, and not Baldessari or On Kawara, that inspired Newgarden's conceptual comics, this Nancy comic has a precedent that is shared with Magritte.

Paul Bilhaud, member of the Incoherénts, a group of 19th century Parisian painters, illustrators, writers and satirists, created this illustration: "Negroes Fighting in a Cellar at Night" in 1883. To quote Phillip Dennis Cate, "This is the first documented monochromatic painting. Before Kazimir Malevich, Ad Reinhardt, or the numerous other 20th-century practitioners of black-on-black painting and its color variants, Bilhaud is the father of a reductive art, although his purpose was hardly related to that of his succesors." (The Spirit of Montmartre, p. 31) Indeed, Bilhaud’s aim here is not to create the last image anyone can ever create, but to make a joke. A racist joke, but a joke nonetheless.

Still, it’s unlikely Ernie Bushmiller was up on his history of the 19th century French avant-garde. It’s important to understand that, as a syndicated cartoonist, Bushmiller was required to come up with a comic strip every day. A monochrome with text is a pragmatic solution to the problem of simply having to generate gag upon gag to appease the gods of "the ticking clock and the Looming Deadline" (WADA p.18). In these conditions everything becomes fuel; not just hostility, shame, and fear, but sex, death, love, the printing press, the color options, the film, the frame, etc. This is the industrial-capitalist view of things: increased demand is met with increased productivity; increased productivity leads to innovation.

Increased demand can also lead to hack jobs.

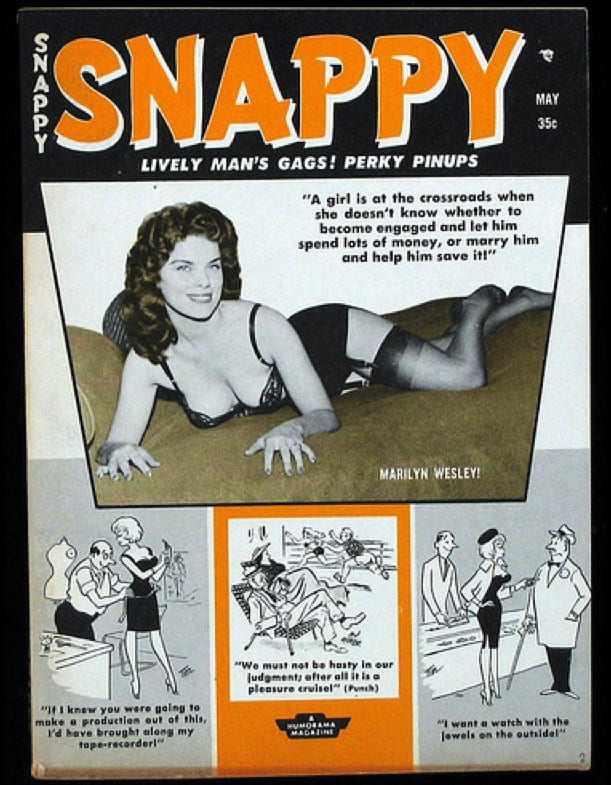

The practitioners of cartoon, gag, and novelty hack-work are folk heroes to Mark Newgarden. Without them the comics industry would not exist. Hacks are the anonymous designers of toilet paper rolls, the craftsmen of the kind of dime-a-dozen gags printed and re-printed in magazines like Humorama and Snappy; publications so bottom-of-the-barrel that cartoonists would not even attach their own names to them, taking up aliases like Mel and Smits when grinding out their gags. Newgarden pays tribute to these unknown soldiers in his own gags, using aliases that often refer to fine artists both historical and contemporaneous. Among the fine art contemporaries whose names are immortalized as monikers in Newgarden's panels are Mark Kostabi and Jeff Koons.

Newgarden on the use of Mark Kostabi's name to sign a gag panel: "Kostabi was a self-styled 'brand' at the time - but clearly an absurd hack."

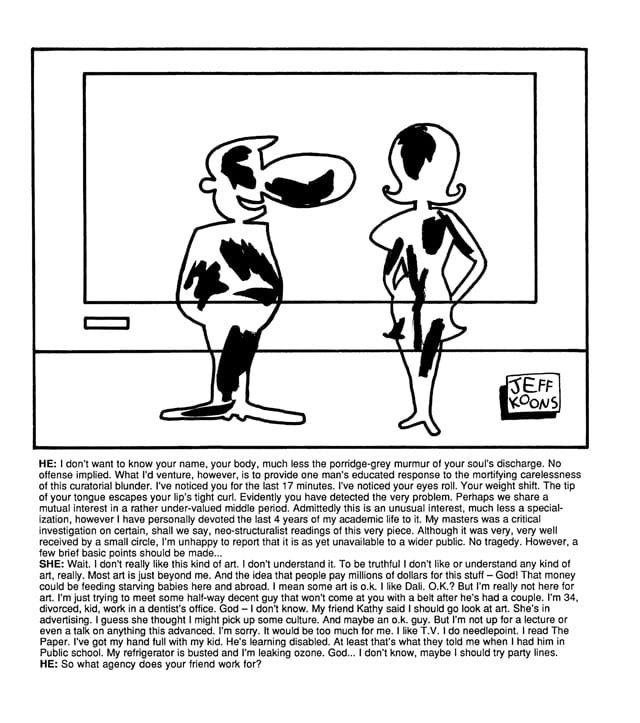

The gag signed "Jeff Koons" involves a protracted and pretentious come-on from the large-nosed guy on the left. The woman insists she is only there because her friend at the ad agency told her she needed to get out and meet people and get over her divorce, but she knows nothing about art and doesn't care. The guy asks what agency her friend works at. It is signed "Jeff Koons". At the time this cartoon was created, Jeff Koons was involved in a copyright infringement lawsuit over his 1988 work "String of Puppies"

Koons had taken the image this sculpture was based on from a postcard. The photograph was by professional photographer Art Rogers who was not given credit or compensation for the use of his image. Koons had also gotten into trouble for using the likeness of the Pink Panther and Michael Jackson in other sculptures. Newgarden described his rationale for appropriating Jeff Koon's name thusly: "Eventually everything becomes Jeff Koons work. So...I'll just sign his name... and head him off at the pass."

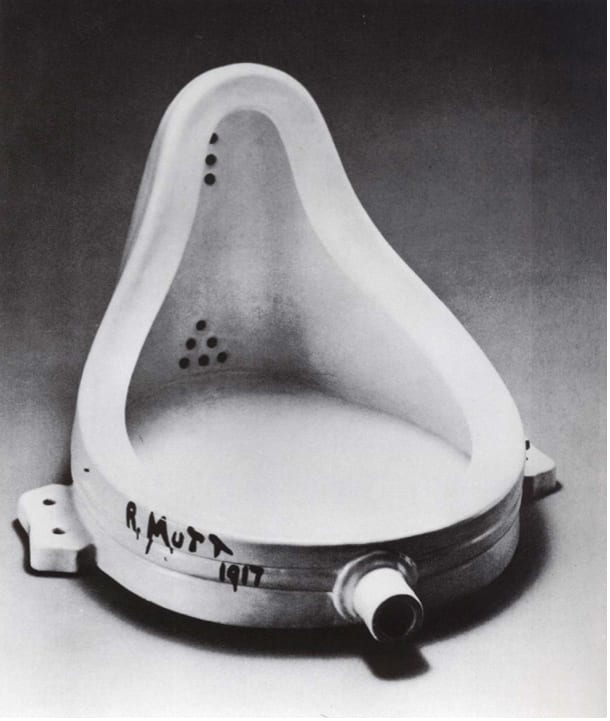

Finally, in "Slab Happy", a weary, torpedo-breasted, giant-nosed lady attends the funeral for a man we may assume is her giant-nosed husband. The 100-odd word caption begins "This is us. This is us waking up. This is us getting out of bed. Up out of bed. To put the water on. For coffee. This is us awake. We're awake now." It follows in the same cadence. "This is us needing TV on. This is Bugs Bunny and Friends on. This is us." Gradually a portrait of hellish marital banality is painted, and the gag transcends jokes about jokes, and in it's own cross-purpose way is more affecting and human than any art-as-art could be. The patently ridiculous and absurd characters are alarmingly articulate and human. It is signed "R. Mutt" in reference to Duchamp's Fountain.

Newgarden is a fan of Duchamp. The problematic issues of appropriation brought about by Jeff Koons are waived in the case of Duchamp, because, to quote Newgarden "toilets are funny." As for appropriation in art, "he was the first and best at this game." But "he was smart and quit the 'art' game to play the chess game. Which has better odds if you're smart."

In my email exchanges with Newgarden, he betrayed a view of fine art as an elaborate mechanism for valuation that has little to do with communication, creativity, or truth. Ironically enough, a similar critique of the art establishment is what inspired the minimalist and conceptualist movements in the first place. Of course, the conceptualists are the current establishment, and that cycle of valuation continues.

In Richard Prince’s joke paintings, Newgarden merely saw a formula at work: “Re-contextualize the familiar; make something ‘small’ something ‘big’ (physically), obfuscate; substitute the vague for the specific, the arbitrary for the intentional, misdirect, leave more ideas open than illuminated. In short; the old dependable.”

Yet it is entirely possible that Prince is doing “the old dependable” not because he is lacking in vision, but because he is playing his own joke; using his expertise in the alchemical practice of creating absurdly valuable art objects to plant expensive works of profane pulp dumbness into the major museums and prominent art collectors’ homes of the world. Only one thing is certain: a painting will never be as funny as a toilet.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Bushmiller, Ernie, and Brian Walker. 1988. The best of Ernie Bushmiller's Nancy. Wilton, Conn: Comicana Books.

Newgarden, Mark, and Dan Nadel. 2005. We All Die Alone: A Collection of Cartoons. Seattle, Wash: Fantagraphics.

Spector, Nancy, and Richard Prince. 2007. Richard Prince. New York: Guggenheim Museum.

Prince, Richard, Bernhard Bürgi, Beatrix Ruf, and Gijs van Tuyl. 2002. Richard Prince: paintings, photographs. Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz.

Cate, Phillip Dennis, and Mary Lewis Shaw. 1996. The spirit of Montmartre: cabarets, humor, and the avant-garde, 1875-1905. New Brunswick, N.J.: Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum.