Cartoonist Frank Modell once related a conversation he had at a party:

Cartoonist Frank Modell once related a conversation he had at a party:

"What do you do?"

"I'm a cartoonist."

"I love cartoons. Where do you publish?"

"The New Yorker."

"I love The New Yorker. What's your name?"

"Frank Modell."

"Yes? [Pause.] I've never heard of you."

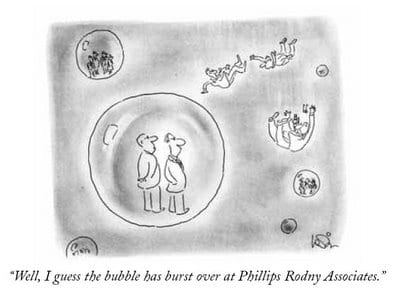

Arnie Levin is one of the many New Yorker cartoonists and cover artists whose style probably isn't immediately identifiable to readers, but whose constant presence since 1974 has contributed incalculably to the magazine's identity and success. "Howard, I think the dog wants to go out," says an aproned woman to her pipe-smoking husband in Levin's most popular Cartoon Bank image. Their pet, dressed to the nines under a top hat and cape, waits patiently. In another popular Levin panel, a woman returns an item to a department store, explaining, "It's fancy-schmantzy. I just wanted fancy."

In person, Levin turns out to be a remarkable example of cognitive dissonance. Born in 1938, the diminutive Levin sports the shaved head, handlebar mustache, and slightly rolling gait of a badass biker. Much of his upper body is tattooed with ornate Japanese imagery by a renowned yakuza body illustrators. And the more you learn about his life, the wider the gap between creator and creations seems to spread.

In person, Levin turns out to be a remarkable example of cognitive dissonance. Born in 1938, the diminutive Levin sports the shaved head, handlebar mustache, and slightly rolling gait of a badass biker. Much of his upper body is tattooed with ornate Japanese imagery by a renowned yakuza body illustrators. And the more you learn about his life, the wider the gap between creator and creations seems to spread.

Levin served in the Marines before winding up as an aspiring painter amid New York City's late-fifties beatnik heyday. "Swept up in the glamour of the beatnik era," as he puts it, Levin co-operated an espresso house that hosted readings by the likes of Allen Ginsberg and Jack Kerouac. He worked parties as a rent-a-beatnik, encountering Bob Dylan, another new kid in town, during one such event. At Push Pin Studio, then at the height of its influence upon the design world, he was plucked out of the messenger pool by Milton Glaser, who recommended him to Lee Savage's Electra Studio, famous for its forward-looking trailers and commercials. After leaving Electra, Levin was recruited for The New Yorker by art director Lee Lorenz in 1974.

After taking up motorcycling at age of fifty-nine, Levin celebrated his new hobby with the aforementioned flurry of tattoos. He's given up biking in the interests of personal safety, however, and now resides more or less quietly on Long Island in New York with his wife.

RICHARD GEHR: You're a New Yorker who was raised in Florida. Where were you born?

RICHARD GEHR: You're a New Yorker who was raised in Florida. Where were you born?

ARNIE LEVIN: I was born in the Bronx. We lived in Flatbush, Brooklyn, for a number of years. My mother was a single mom. She was an accountant who wanted to be a writer. Her name was Dorothy Elfenbein. My grandfather Louis was a seltzer man with the truck and everything. He was a very nice man but he got paralyzed; I don't know why or how. My mother married Ernest Levin, who eventually changed his name to Pike. He wanted to be a writer. They both wanted to be fuckin' writers, so it was fine for me to be an artist.

GEHR: Did you have any relationship with your father?

LEVIN: When I went to get a passport, they ask me, "What's your father's name?" I said, "Ernest." And the gal said to me, "No, it's not." I said, "Yes, it is!" She said, "No. That's not what's here." So I called my mother and aunt to ask if Dad had any other names. Nothing. We were there all day calling people. I was getting desperate because we were gonna take a trip and I needed a passport. Then the gal asked me, "What borough did you live in?" I said the Bronx, She said no. I said, "This is impossible!" and asked her what she had down for his name. She said, "E." [Laughter] I said, "E?" "Yes. E. Lawrence Levin." She suddenly wants to get literary!

GEHR: What was your mother's family like?

LEVIN: Her family is sort of dysfunctional once in a while, but very good-natured by and large. She started out as a bookkeeper for one of the real speakeasies in Greenwich Village and ended up working for a Rockefeller Center accounting firm next door to the William Morris agency. She did accounting for James Mason and other actors and would come home with autographs. When she had to work on Saturdays, she'd take me with her. There was a little room off to the side, and she'd sit me down with a yellow pad and pencils. I'd sit there and draw for hours, just looking out at the street. My reward for this was dinner at Tad's Steakhouse on 42nd Street. And there was a nineteen-cent bookstore where I would get a dollar's worth of New Yorker magazines.

GEHR: Did you continue drawing through school?

LEVIN: Miami Technical Senior High School's commercial art class turned out to be incredible. It was three hours a day for the first two years, just learning art. And then supposedly there were related courses like English and math, which were all taught by artists, for another three hours a day. But they didn't each anything. Everybody just drew all the time. And this guy Kenneth Bare taught from Kimon Nicolaides's Natural Way To Draw. I got offered a scholarship to the University of Miami either for art or for dancing.

GEHR: Were you a dancer too?

LEVIN: I was dancing bop [chuckles]. I won a citywide dance contest in Miami, and my partner and I were on television. My partner and I were up against this brother-sister team. It was very dramatic.

GEHR: Did you accept the scholarship?

LEVIN: I went to see the university's art teacher. I looked at his paintings and I'm going, "Nah…" By then I was all fired up for class because Kenneth Bare had told me about Pollack, who dribbled paint. So I was dribbling paint. I was a young expressionist.

GEHR: How did you end up in the Marines?

LEVIN: This guy said that if we joined the Marines Reserves while we were still in high school, and went to meetings for a couple of months, it would give us seniority. It sounded sensible. When I got in, they found out I was an artist, so I silk-screened for them even before basic training. So we went to Parris Island and I thought, this is just wonderful, it's like being in a movie! Everyone played the parts they were supposed to play. And of course I ran afoul.

GEHR: You were eventually transferred to California, right?

LEVIN: In Parris, our little group is gathered around and Lieutenant comes by and asks, "What do you wanna be?" "Infantry, sir! Infantry, sir!" And he gets around to me and I said, "I'd like to be a photographer" [laughter]. He's, like, looking for something to hit. And I said, "I'm an artist. You might as well use me for something good." They had photography school. I worked like a son of a bitch and came out third in the class. When my turn came to pick where I'd be stationed, I saw "Mojave" and asked, "Where is Mojave?" This guy takes out a big map and the two of us look and look. Another guy comes over and the three of us look [laughter]. I said, "If you can't find it, that sounds good. I'll take it."

GEHR: Did you make any art out there?

LEVIN: Actually, yeah, I did. I don't remember what kind. I played bongos; that was fun. I had watercolors. They called me "The Tourist" because I would go out in the desert and draw. Also, when I first got up to the base you had to do KP, so they put me in the salad room. We cut up salad and stuff. One thing we did was make a large tray of cottage cheese. We would put it out, spray a little paprika on it, and people would eat this very unappetizing thing. So I decided to make a sculpture with it. I started off with a reclining nude and got rave reviews. The added benefit was that instead of mauling it, people ate around the edges; so we could just fill it in and use it for another meal. I did so well with the first one that for the second I did the White House. I used parsley for trees. Nothing really spectacular, but everybody loved it.

GEHR: How did you begin cartooning?

LEVIN: When I went back to Miami, I was hanging out with all these musicians; the artists bored me, but the musicians were a lot of fun. And one night I got into a car crash. I ended up at home with a broken hip, two dislocated shoulders, and a couple other miscellaneous things.

GEHR: There goes your dancing career.

LEVIN: Yeah [laughs], although by then I wasn't dancing that much. Anyway, they put a pin in, and I had these dislocated shoulders, so I had nothing to do. My mother had these Writer's Digests, so I'm looking and it says you can submit cartoons. You were supposed to send in around twenty drawings. I said, "Alright, what do I got to lose?" So I got a stack of typewriter paper; and I don't know what possessed me to go for a bamboo pen [laughter], because it's the clumsiest instrument known to man. I started to do roughs. I would sit on the edge of the bed and draw like this… [Laughter]

GEHR: You were all hunched up, immobilized.

LEVIN: Yes, except for a little wrist movement. So I did twenty drawings and sent them to Playboy. Then I got into an argument with my mother and decided I'd had it with living with her. This was after I got out of the Marines, about 1958. I was already living in New York but I was driving back and forth.

GEHR: What happened back in New York?

LEVIN: I went to the YMCA and they said, "Sorry, you can't come in with a wheelchair." [Laughter] I said, "The hell I can't!" and really gave it to them. After I got out of the Marines, I wanted to study at the Art Students League of New York. That was my dream. And thanks to the GI Bill, I could.

GEHR: Did Playboy buy any of your drawings?

GEHR: Did Playboy buy any of your drawings?

LEVIN: About six months later, my mother calls up and says, "I got a letter for you from Playboy. They bought a drawing and they want you to finish it." She sends it up, and I look at it and think, what finish? There's more? So I looked in the magazine and noticed the grays in 'em. And there were two other roughs they wanted to buy in the envelope, too. So I finished the first drawing and sent it back. Six months later they sent me a check for $80. OK! So I finished the next two drawings and six months later got checks for $85 and $90. So it took me a year to make about 200 bucks! [Laughter] This was not a profession for me – or anyone, for that matter.

GEHR: And those were the only cartoons you sold for a very long time.

LEVIN: I picked up cartooning again much, much later. I started studying at the Art Students League at the height of expressionism. At the time, I was living on 91st Street, sharing a room in a brownstone with a guy who was going to Connecticut School of Broadcasting. I had been hanging around a coffee shop called the Seven Arts Coffee Gallery, upstairs on Ninth Avenue. I had been hanging around and, well, I ended up staying there.

GEHR: The Seven Arts Coffee Gallery was kind of a beatnik hot spot, wasn't it?

LEVIN: It didn't open until eight at night. It had poetry readings, folk singers, and an art gallery. It had everything. It was owned by John Rapanick, a burly loan shark from Jersey City who'd gone into the service and had freaked out, basically. Friday nights were open poetry readings, so you had everybody and their brother. And then you'd have Ginsberg reading. And Corso, Kerouac, Hugh Romney, AKA Wavy Gravy, and Peter Orlovsky, who was Allen's lover.

GEHR: Did you write poetry?

LEVIN: No. I was painting. My partner, John…I say "my partner" because after a while I became second in command and became his partner. About four of us slept on the tables in sleeping bags. I was mainly working in the coffee shop, but then John got me a studio. One of the empty apartments on Ninth Avenue just below 42nd Street. We didn't pay any rent. He said, "Hey, got you this place." So I'm in there painting one day, and suddenly the wall comes out, there's a hole in the wall – boom! Plaster comes down, and there's this hole and these construction guys. Smoke is coming in… The guy says, "This building's coming down. You gotta get out of here!" [Laughter] So I ran and got John, and we grabbed the paintings and ran up Eighth Avenue.

GEHR: How long did your painting phase last?

LEVIN: I gave up painting. "You have to be together," I said, "and I cannot conceive of myself ever being together enough to be able to manage a studio and have all this stuff you're supposed to have. So I decided to give up painting. Then what? I was just of floating around. One day I said, "I'm gonna buy a black notebook and a Rapidograph pen." Two nights later, I'm walking by the 8th Street Bookstore. I looked in the window and there were two books by André François. The reason I had not gone into cartooning was I thought it was kind of corny although I loved some cartoonists, like Vip. I thought, "You know, cartoons don't have to talk down. Cartoons can still be beautiful." So the next day I went up to the O'Donnell Library on 53rd Street, across from MOMA. I went to the picture collection, started taking out books, and started drawing.

GEHR: How did you end up at Push Pin?

GEHR: How did you end up at Push Pin?

LEVIN: It all started with me leaving a rental house next door to Yonah Schimmel Knishes on Houston Street. The house turned out to be an amphetamine den filled with people, but I had no idea who they were. Later I took an illustration night class at the School for Visual Arts from Bob Blechman and Charlie Slackman. Blechman sent me over to Push Pin and I become their messenger. One of our tasks was to get research photos at the photo library for Milton Glaser and Seymour Chwast and those guys. And, man, they'd gobble this stuff up. Picking this stuff out and watching them at work was a complete blast.

GEHR: How long were you a messenger?

LEVIN: When I was in Bleckman and Slackman's class, they assigned a storyboard. I did maybe sixty panels of storyboard with collages and everything. It folded out and I made a soundtrack for it. It was big. About a week later, Bleckman asked me if I was still a messenger and I said, "Yeah." About a week later, Milton Glaser calls me into his office. "How would you like to be in animated film?" he asked me. "Oh no, I'd rather be a messenger!" [Laughter] So Glaser sent me up to Lee Savage at Elektra Films.

GEHR: What did you do there?

LEVIN: I did animation for a number of years. Then Lee Savage had a fight with his partner and they decided to fire everyone Lee had hired and went in a different direction. I started to free-lance. One of my problems is I've never really been good at copying the same drawing twice, which comes in handy for animation.

GEHR: How did you sell your first cartoons to The New Yorker?

LEVIN: My first wife and I were living in Forest Hills, and I was just drawing, having fun with all kinds of drawings. I was working with big drawings, for no real reason. I called Bob Blechman, who's sort of mentor of mine, and Bob said, "You know, they've got a new art director at The New Yorker and he's looking for new people. Why don't you do something and I'll see if I can get you up there." So I went and I did a couple of roughs, and Bob called Lee Lorenz and said, "I've got one of my students here. You should really see his work." And Lee said, "Can you come over on Tuesday?" So I brought these things in but he didn't seem too enthused. They were all cover ideas. Then he says, "Can you finish these two?" And I thought to myself, "What is a New Yorker finish?" I started coming in with big drawings, little drawings, versions, watercolors, ink, everything technique. Nothing, nothing, nothing. So the next time I came in I said to Lee, "You've never seen my portfolio" – which consisted of these big, wild, goofy drawings I did for no reason. He looked through them, held one, and then two days later called up in the afternoon. Lee asked me if I could one of the drawings in black-and-white. So I did it, hopped on the subway, and ran right in with it. He said, "You didn't have to come in today." I started submitting cartoons, and I started selling and having fun with them. I got a contract within the first year.

LEVIN: My first wife and I were living in Forest Hills, and I was just drawing, having fun with all kinds of drawings. I was working with big drawings, for no real reason. I called Bob Blechman, who's sort of mentor of mine, and Bob said, "You know, they've got a new art director at The New Yorker and he's looking for new people. Why don't you do something and I'll see if I can get you up there." So I went and I did a couple of roughs, and Bob called Lee Lorenz and said, "I've got one of my students here. You should really see his work." And Lee said, "Can you come over on Tuesday?" So I brought these things in but he didn't seem too enthused. They were all cover ideas. Then he says, "Can you finish these two?" And I thought to myself, "What is a New Yorker finish?" I started coming in with big drawings, little drawings, versions, watercolors, ink, everything technique. Nothing, nothing, nothing. So the next time I came in I said to Lee, "You've never seen my portfolio" – which consisted of these big, wild, goofy drawings I did for no reason. He looked through them, held one, and then two days later called up in the afternoon. Lee asked me if I could one of the drawings in black-and-white. So I did it, hopped on the subway, and ran right in with it. He said, "You didn't have to come in today." I started submitting cartoons, and I started selling and having fun with them. I got a contract within the first year.

GEHR: Your first few New Yorker contributions look like art drawings. Then all of a sudden you've got a definite cartooning style.

LEVIN: As I was drawing the third cartoon for The New Yorker, I got to the hands. But I couldn't draw the hands. So finally I said, "Fuck it, maybe they won't notice." I thought they would immediately look at the drawing and go, "Look at those hands!" But they didn't say anything. And I thought, "You know, maybe this is not set in stone." [Laughter] And that really loosened me up.

GEHR: Do you remember how much you got paid for your first New Yorker drawing?

LEVIN: $240, which was also what my rent was. I tried to get a job at as a taxi driver, but they were on strike. [Laughs] The rent was due, but my wife was working.

GEHR: How many ideas would you submit a week?

LEVIN: About 30, although I've gone up to 50, and then I saw Lee make a face, so I thought maybe I'm doing too much. I was not a cartoonist, right? So I never had the opportunity to do all the bad ones, the guys dueling with swordfish [laughter], the cartoon garage sale ideas. I never got that out of my system, or even tried. Sometimes, I would do three versions of the same concept and let Lee pick the best version. I've done more than 700 cartoons, and they only changed two words.

GEHR: Which ones?

LEVIN: It was like a campaign headquarters and two guys are carrying the senator, who looks dead. And the guy is saying something like, "Well, it was either the cannoli in Little Italy" or something else in Westchester. And they said, "Change that to 'divinity fudge.'"

GEHR: Many of your best cartoons are about literalizing clichés.

GEHR: Many of your best cartoons are about literalizing clichés.

LEVIN: I love words, phrases, and twists. You've got to get the rhythm, the right amount of syllables. It's gotta flow. After you do it for a long time, you don't think about it.

GEHR: What are the tools of your trade?

LEVIN: Pen and ink. I like to have a lot of choices because I don't think that any one thing can do everything I want it to. I did a lot of illustration. I use Gillette steel pens for cartoons. I bought a box of a hundred Ester Brook pen points in a Planned Parenthood thrift store and they turned out to be perfect for the New Yorker drawings that I did the first number of years

GEHR: I understand you used to own an antique store in Brooklyn, too. What was it called?

LEVIN: The Elusive Spondulla.

(Special thanks to Ben Horak, Kara Krewer, Janice Lee, and Madisen Semet for transcription assistance.)