This year’s festival at Angoulême was a success, both in terms of popular interest and artistic quality. There are no two ways about it. Its director Franck Bondoux reported more than 215,000 guests over the weekend, up somewhat from previous years, and Saturday especially was close to overcrowded, with the main tents temporarily having to close their doors to manage the influx. At the same time, festival president Art Spiegelman not only (co-)curated two extraordinary shows, but also brought a lot of international interest, tempering the francophone myopia that has long plagued the festival (and which I addressed in last year’s report). On the balance, I would call him the best president of the last decade, presiding over one of the best festivals in that same period.

Yet problems persist and one is tempted to see them exemplified by this year’s Grand Prix winner, Jean-Claude Denis, who will preside over next year’s fortieth anniversary. It is not that the Angoulême academy of past Grand Prix winners, which selected Denis, has all that much say in the planning and execution of festival, but their selection of what is arguably the highest honor formally bestowed on comics makers worldwide is still strongly symbolic, and the president each year has a unique chance to shape its artistic direction and eventually to point the way forward as part of the academy that chooses his or her successors.

But then, the Angoulême academy has always tended to award their peers, mostly those of the seventies and eighties generations who continue to dominate its ranks, which has the further problem of favoring male French creators by a wide margin. In 39 years of existence, and among 44 inductees (certain years have seen more than one person selected), 34 grand prix winners have been French, with even Belgium trailing far behind at four, and the rest of the field consisting of three Americans, one Italian, one Swiss, and one Argentine. Of all 44, only two are women. Although hardly more than moderately popular or critically acclaimed, Denis is a neat fit: he studied, and has frequently collaborated with the artistically congenial Martin Veyron (Grand Prix 2001) and plays in a band with Dupuy and Berberian (Grand Prix 2008) with whom he has also collaborated on a book.

So the Grand Prix this year seems a bit of a step back, but one could hardly have expected this august group to have selected a foreigner two years in a row, and the many younger, already deserving French or France-based Grand Prix prospects -- there were rumors about David B., Christophe Blain, and Marjane Satrapi -- will surely get it in the future. And in any case, this year’s Spiegelman presidency demonstrated in spades the international potential of the position. It just may happen that once the younger, more internationalized generation that is starting to join get more of a say, we will see a more international, gender-equitable academy.

In any case, there genuinely seemed to be more international guests and visitors at this year than any time in recent memory, and the programming gave international comics a lot of space, with panels and interviews focusing on significant Anglophone creators and editors from the eighties till now -- Brian Azzarello, Charles Burns, Eddie Campbell, Aline Kominsky-Crumb, Francoise Mouly, Joe Sacco, Spiegelman, Craig Thompson, and others (Chris Ware was supposed to appear but had to cancel). And in a welcome innovation, most of these people were, as far as I could tell, even competently interviewed -- otherwise a rarity at the festival.

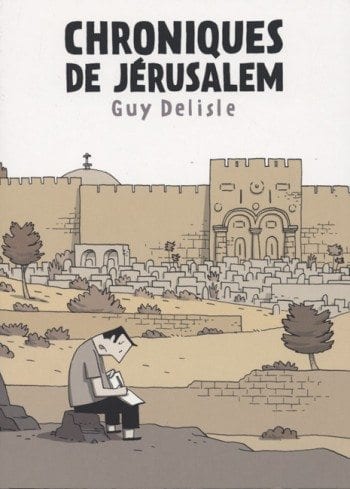

Add to this wide-ranging programming featuring European cartoonists (Fred, Guy Delisle, Maximilien Le Roy, Francis Masse, Lorenzo Mattotti, José Muñoz, Isabelle Pralong, Joost Swarte, and many more) and exhibition showcases -- within and without the festival’s own framework -- focusing on such diverse areas of the world as Armenia, Palestine, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, and Turkey, as well as others in group shows, and you have a rich international tapestry, even if the individual efforts were highly uneven in quality.

The problem child of many years, manga, however seems finally to have become an orphan. For years consigned to the back of already crowded tents, or out of the way, this year Japanese comics were given a more prominent place in a large tent on the centrally-situated Champ de Mars, but unfortunately had to share it with American superhero comics. It was just as well, I guess, because most of the manga publishers and fans seem to have realized that the festival does very little for them and thus mostly stayed away, leaving visitors with slim pickings indeed: a few booths, a stage with sparsely attended live drawing, and a flat screen exhibition area promising interaction but delivering blandness looped. It was a pathetic, but surely also a natural development for a festival that has never been able to accommodate the admittedly quite different manga subculture under its aegis, and which additionally has seen the emergence in the last five years or so of a more focused competitor in the form of the large Paris-based annual Japan Expo.

In general, however, the awards -- or Fauves as they were dubbed when Lewis Trondheim overhauled the system in 2006 -- are losing their focus. Trondheim’s much-needed transition into the selection of a handful of essentials from a list of nominees has been modified and tweaked each year, resulting in an increasingly confusing and commercially determined field. Complaints from mainstream publishers that the awards primarily catered to “alternatives” resulted in a special Fauve for "Best series" a few years ago; the following year, each "essential" was given a title that confuses more than it elucidates (see above); and now, in a move of blatant pandering the festival has inaugurated a special award for best crime comic, sponsored by their commercial partner the French railroad company SNCF. Ever a headache for the festival, these constant changes in themselves devalue what remains Europe’s most prestigious comics awards. (And don't even get me started on the evolution of the audience/SNCF/Fnac award -- I wouldn't be able to finish). It seems high time for someone in the festival's steering body put their foot down.

As initially suggested, the selection of Denis for the Grand Prix can (somewhat unfairly, but still relevantly) be seen as symptomatic of several of these issues, but above all the ongoing struggle with the past not only of the festival, but of the comics community at large. So much has changed in the last twenty years -- commercially as well as artistically -- that most institutions are still playing catch up.

From this perspective Angoulême is doing about as well as any event of its kind anywhere in the world. Its problem, but also its main asset, is that it aims so widely, fathoming if not the whole of comics, then as close as you get to it in one place: from the signing galleys of mainstream houses Glénat or Soleil to the smoke-filled back rooms of the increasingly interesting fringe festival F.OFF (now in its third year!); from the throngs of kids flooding the Monde des bulles tents, colored pencils in hand to contemporary stars cartooning to live music at the so-called Concerts de dessin; from the gathering of the comics historian nerd mind in the Platinum Group at the comics museum to that of the hipsters at the Nouveau monde booth afterparties; with visits from the cultural minister in addition both to a former and a coming presidential candidate, all seeking to bolster their image at this, one of the largest cultural events in France, and with the Francophone comics community out in force, mingling with visitors from all seven continents, this remains the comics Babel, for better or worse.

Check out the Comics Journal/Metabunker photo series from Angoulême here. Apologies to my colleague Erik barkman for stealing his title.