The graphic novel debut of the San Francisco-based cartoonist, Sophia Foster-Dimino, comes in the form of an intimate little brick of a book. Collecting a number of issues of her self-published minicomic series as well as a few new chapters for the collected Koyama Press edition, Sex Fantasy is a recursive pleasure, looping in on itself. I had the pleasure of working with Sophia on our webcomic Swim Thru Fire for Hazlitt, seeing for myself how she was able to take a loose script and evoke spaces tight and vast, characters both terribly open and vulnerable as well as reclusive and hidden. I spoke to Sophia by Skype. Readers looking to learn more can listen to Sophia’s appearance on Inkstuds, and our appearance on Kris Mukai’s Young Talk. —Annie Mok

The graphic novel debut of the San Francisco-based cartoonist, Sophia Foster-Dimino, comes in the form of an intimate little brick of a book. Collecting a number of issues of her self-published minicomic series as well as a few new chapters for the collected Koyama Press edition, Sex Fantasy is a recursive pleasure, looping in on itself. I had the pleasure of working with Sophia on our webcomic Swim Thru Fire for Hazlitt, seeing for myself how she was able to take a loose script and evoke spaces tight and vast, characters both terribly open and vulnerable as well as reclusive and hidden. I spoke to Sophia by Skype. Readers looking to learn more can listen to Sophia’s appearance on Inkstuds, and our appearance on Kris Mukai’s Young Talk. —Annie Mok

ANNIE MOK: The title Sex Fantasy seems a little bit like a feint, because the book is kind of about sex and kind of not about sex.

SOPHIA FOSTER-DIMINO: Yeah, for real [laughs].

MOK: How did you come to this title?

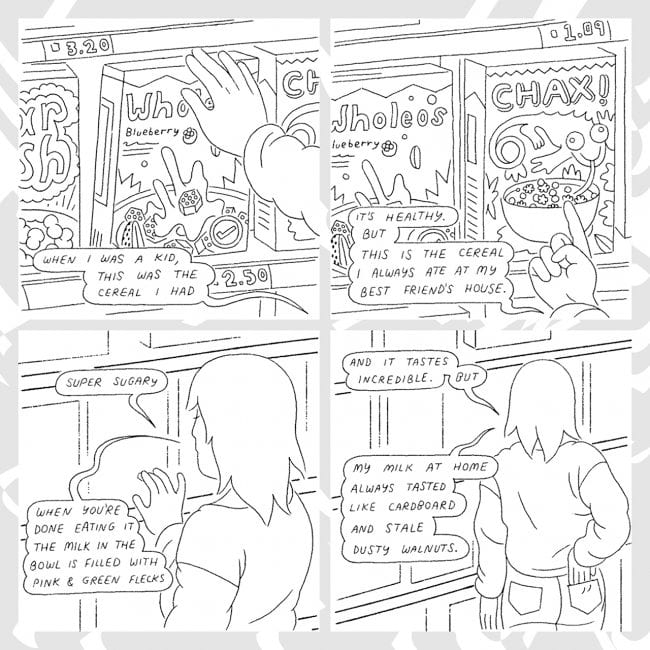

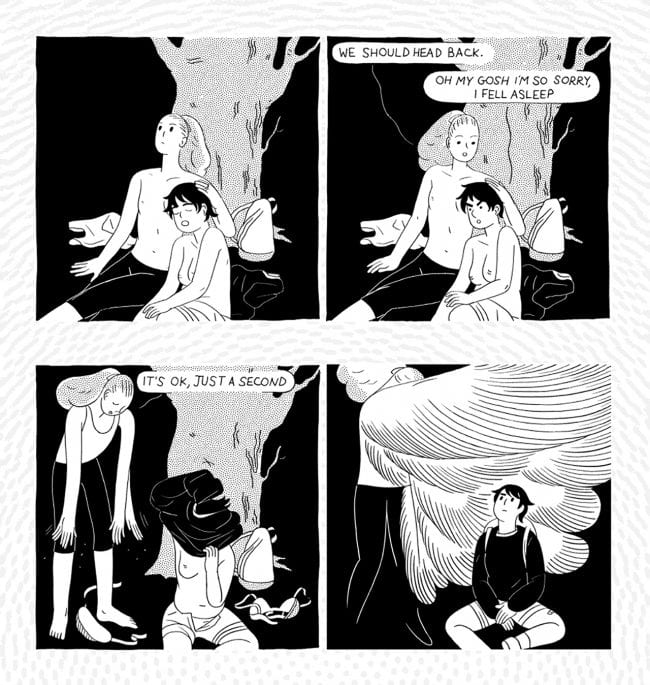

FOSTER-DIMINO: When I picked the title, I didn’t even know I was gonna make it a series. But I wanted something that was striking and intriguing, and maybe a little misleading. People who have read my work closely and have followed along with the whole series are like, of course it is about sex fantasies for sure, even the non-explicit ones. And there are undercurrents of that, like issue 5 is about two women going on a date for maybe the second or third time, so there’s tension, and then issue 8 is sort of this intense sexualized dominant-submissive dynamic between two people in a grocery store. Then in the last issue, I wanted to full-on address the concept of sex fantasies, so that’s probably the most direct take on the concept. For the other ones, that are more subtle, I wanted to explore ideas about self-expression and identity. How people change the way they conceive of themselves, whether they’re alone or with people they trust, people they just met or people they know really well. So those pressures can change how we see ourselves, which ties into those sex fantasies. The idea of a sex fantasy is you’re imagining a person who you might not know very well and what they’re like and how they get along with you, but you’re also imagining a more perfect embodiment of yourself, a scenario where you can be the person that you truly want to be.

MOK: There’s a number of transformations throughout the stories. In issue 5, one woman sprouts wings and the other one says, “Oh, I didn’t know you could do that.” Can you speak to the theme of transformations within the comic? And also this general theme of fluidity that goes through the comic; there’s kind of a fluid narrator point of view. What is that fluidity like for you as an author?

FOSTER-DIMINO: I started working on the series as prep for this long story, which is actually still incomplete. I got stage fright, which I think a lot of cartoonists get with a longer work, where there are more expectations as to the format and the narrative structure. So doing these shorter, self-contained little minicomics gave me the opportunity to exercise my particular storytelling style. So I tried a lot of different things. I was really intentional about changing up the style, the point of view, the tone—to do some stories that were cute and sweet, some that were funny, and some that were darker and bleak, and some that were maybe a little scary… I suppose the parallel there is, since it deals so much with identity and fluid identity and the evolution of identity both intentional and created by peer pressure, this sort of panoptic-influence, or the expectations of society at large.

MOK: What is a panopticon?

FOSTER-DIMINO: It’s a Foucault term, that you can influence people’s behavior by making them think that they’re being watched by someone. Foucault had this concept of a prison where all of the cells were in a circle and there was one watchtower in the center. The idea being that you wouldn’t even need to show a guard there, but if people thought there was a guard there they would modify their behavior. Which I sort of get in my life to certain degrees. When I publish work, I sort of imagine who’s going to read it and maybe while you’re developing a story that turns the needle, you change a sentence when you think of how someone in particular might be interpreting it. I think of identity transforming in that way, and I think the collection allowed me to transform the storytelling style. So there’s different expressions of identity but also different expressions of who I am as an artist.

MOK: I love this fluidity. There’s a fluidity to the characters where you get a sense that they’re generally queer but you don’t necessarily know how they identify. How did you go about crafting these characters?

FOSTER-DIMINO: I would say that issue 5 is the most transparently queer-coded story, if you wanna frame it that way. It was definitely about my experiences dating at the time and thinking about more loose or open-ended expressions of identity. When I make characters, I focus in on a few traits that I consider essential. I consider it less prudent for them to come out and say how they identify, a breakdown like you’d have in a dating profile or something [laughs]. It’s more of like, if you saw someone on the subway you’d maybe have one or two details about them, and everything else is left up to your imagination. Which is intentional, the characters maybe become fantasies in the eyes of the reader, and they’re free to interpret them however they want.

MOK: This method of directly addressing the reader, was there an influence from somewhere?

FOSTER-DIMINO: I was conceiving them as almost diary entries or stream-of-consciousness declarations. I was thinking about all the fleeting impulses I’ve had or the desires or the aspirations, and many of them are conflicting. I don’t know offhand if there’s a direct influence for it. I think at the time I was reading some poetry, listening to a lot of music, thinking about the things that can be done in music and literature that comics don’t seem to attempt as much.

MOK: There’s a rhythmic quality to Sex Fantasy. In the We Should Be Friends [podcast] episode about you, the friends said that some of them sound like song lyrics...

FOSTER-DIMINO: I have always liked writing. When I was younger I wanted to be a novelist before I even really got into drawing.

MOK: Do you still want that?

FOSTER-DIMINO: I’m kind of at odds with it because the comics that I like best are the ones that originate from the visual pacing rather than the writing. All of my work starts from a script first, which is the way I’m more comfortable working, it comes to me faster, but I also feel it’s limiting. I’m challenging myself to do more non-verbal visual sequences and see what I can do with storytelling in that sense.

MOK: If you can say anything about it, there’s a follow-up of sorts to Sex Fantasy coming, is that right?

FOSTER-DIMINO: Fuck Reality? That’s a mini that I’m hoping to have by SPX. I am working on something longer for Retrofit that I’m hoping to have done by the end of the year, and in that one I’m pushing myself to have a more traditionally structured comic with plot, characters, consistent storyline. It’s still a bit experimental.

MOK: Is that the one with the kids that you told me about? Trapped in the house?

FOSTER-DIMINO: No, that was my Retrofit comic that’s been shelved. The horror story? I completed that comic twice and scrapped it both times.

MOK: Who are you, Michael DeForge?

FOSTER-DIMINO: If Michael DeForge can do it, any of us plebes can. [they both laugh] I was working on a comic called Alhambra, a 60-page comic, scrapped it twice… I still wanna finish it one day but I think I have more interest in experimental stories, and this was a very panopticon-inflected traditional story that I just don’t think I had the skills for. Completing Sex Fantasy taught me a lot about the kind of stories I want to tell. It requires that I kill my idols and let go of my major influences to chase that vision.

MOK: What does that vision look like for you right now?

FOSTER-DIMINO: Right now, I have this longer story scripted that I wanna work on. It’s about bisexuality and loss and isolation.

MOK: I’m already sold!

FOSTER-DIMINO: Oh, good [laughs], that’s the elevator pitch. It’s about internal monologues, which is a parallel to Sex Fantasy, and intimacy and wanting to be close to people. But told over a longer, more involved story with more direct character development. The mini I want to do, Fuck Reality, is just because I wanted to have a venue for me to do short, 10-30 page minis for every show to keep experimenting, I always think that’s going to be a necessary part of my process.

MOK: Sex Fantasy was made over the course of little cheap $1 minis, for at least the first bunch of issues. Were the last issues made for the book particularly?

FOSTER-DIMINO: The last few issues have never been published, and they’re quite long, I would have a hard time making minis out of them. They’re too thick to staple. I wanted to give the book some closure in the form of material that was specifically intended for that format. The sort of cheap minis, that context gave me freedom that I was lacking, to experiment with ideas that I thought might not be immediately recognizable to people.

MOK: What fests are you doing this year?

FOSTER-DIMINO: I’m doing SPX, that’s where Sex Fantasy is debuting with Koyama Press. A lot of other cool books are coming out in that Koyama slate as well, Hannah K. Lee’s book is coming out. I’m doing CALA in December in LA… I would love to take a semester off [from teaching] and see really small zine fests all over the country.

MOK: What’s it like connecting with people at festivals, and what’s the response been like to Sex Fantasy?

FOSTER-DIMINO: It’s been really great. There’s no way to not make this sound corny, but I’ve been really, really touched to see people’s reactions to it. For me, I kind of make these issues in a frenzy of introspection, and deep, shameful personal feelings [laughs].

MOK: I noticed.

FOSTER-DIMINO: I just feel, as I put these things into the world, this cascade of self-consciousness, and pre-emptive alienation [laughs]. So it’s just honestly fantastic that people are able to join me in that vulnerability and say that they’re able to identify with a particular story. It’s cool to see which ones people find are their favorites. I have judgements about each, how successful they were, but every issue I’ve done is someone’s favorite, and that’s incredible. It makes me so happy about the book collection as a whole that all of these issues are shining from the mass for someone.

MOK: What’s your favorite?

FOSTER-DIMINO: The ninth issue is this biographical story about my roommate from college going on this saga to meet her internet boyfriend.

MOK: She’s drawn as a munchkin, like a Little My-sized character.

FOSTER-DIMINO: Yeah, she’s a minuscule, chibi, doll-sized. Not to spoil any of the events of that story, but she and I, especially at that time, shared feelings about being overwhelmed by the world, under-equipped as fresh adults to deal with reality. And that story was emblematic of that state of mind. It’s just fascinating, twisted story that she would tell at parties for years and years after it happened. It’s iconic in our friendship. I wanted a story in Sex Fantasy where I stepped away from myself. Stories 7-9 are about people in my life and experiences I’ve had with them, and the ninth issue I’m most in the background, of that trilogy. The first three issues are really self-centered, all about the ego and the superego. I wanted to have one where I was more of a diligent archiver of someone else’s history… I was tabling at SF Zine Fest, maybe five years ago? Could it have been 2012? And I was working on this longer story, but I just wanted to do something quick. I wound up feeling like that unencumbered format was a lot more appealing to work on for the next several years.

MOK: I love the title sequences, where words are often visualized as snakes or lumbering objects. What was working on that like? I know you do typography as well.

FOSTER-DIMINO: Oh, the cover pages for each one? Each of them has no direct reference to the story, it doesn’t have the characters or any of the scenarios, so it’s not so much an advertisement of the content as trying to encapsulate the vibe. It’s kind of you to say I do typography, I think I still very amateurishly do typography [laughs], but I was interested in a cover that tells you about the personality of the person who made the book, but nothing about the book itself. I was talking to someone about this recently, the idea that we sort movies and books by genre frequently, but the genre of the book has little to do with whether it’s good or not. I’d much rather read a Nabokov story about, uh, what’s a genre I don’t usually like? Like, a rom-com. I don’t usually like rom-coms, but if Nabokov wrote one I would totally go for it. I like this idea of chasing after that ineffable point of view and storytelling style as the thing that draws you from story to story instead of the content, which is so, it really tells you very little about… You could take a movie script, it could be completely a different story in the hands of this or that director. There’s so much about the way a shot, the pose, the way that the actors are instructed to give their lines, that changes so much the meaning of something genuine or sarcastic. The same story could have a drastically different meaning.

MOK: The body language of the characters, which is quite impressive, is always shifting the meaning of the words. Do you watch people closely in real life.

FOSTER-DIMINO: I do [laughs], I think most artists do, I try not to be weird about it. I like to draw in coffee shops and in bars and on buses. I can’t help but pick up really small nuances of people’s conversations. Knowing at the same time, that what I interpret from that interaction might be totally off-base because we’re all living in our own strange individual cultures of semiotics, the meaning of gestures or inflections.

MOK: What’s it like working with Annie Koyama so far? She’s a dream publisher for many, of course.

FOSTER-DIMINO: She’s a dream publisher for me, too [laughs]! Annie’s absolutely wonderful. I wanted it to feel as close to the original minicomics as possible, which is hard for Xeroxed floppies at 4x4”. We did our best given the constraint, and I’m really happy with the result. Annie is so sweet and encouraging, and full of energy and light.

MOK: What does the book’s smallness say to you?

FOSTER-DIMINO: It makes me think of something you can have a private moment with. If you’re curled up on a couch or under a tree in a park, the book becomes your own very intimate portal with this dialogue that you can participate in. I want people to feel like it’s tiny but it’s rich and it’s full and it’s there for them and they can explore it at their own pace.

MOK: How did the stories evolve for you, doing it in this sequential order? You might think, for a book like this, that has a bunch of semi-connected short stories that they might be reordered for [collected] publication. But you chose to present them in sequential order. Perhaps, documenting some kind of process that you were going through artistically or personally. What does the order of the books say to you now?

FOSTER-DIMINO: From the beginning, I was quite intentional about the order and the structure.

MOK: Did you write or outline them all up front?

FOSTER-DIMINO: Not necessarily. I would say by the fourth issue, I knew that I wanted to have a series of trios. One through three, four through six, and seven through nine are all sort of thematically similar. Seven through nine are biographical, about people that I know. Four through seven are about dialogues and people having conversations, although in the fourth issue it’s a person having a conversation with a representation of their negative thoughts, although it becomes more external-facing as it progresses. The overall development of the story is looking inwards to looking outwards and engaging with people. Obsessing over personal identity versus interactions with other people. The last issue, the standalone, is a literal take on the concept of sex fantasy and how it impacts people’s relationships. I usually would only script the next issue I was working on, and I would script whenever I felt like it but would rewrite it every week leading up to the time when I knew I was gonna work on it. The largest gap between issues came between issues six and seven. I was starting this new trio about people I knew. I had a script, which I ended up scrapping, that was about someone I’d been close to. It just felt too voyeuristic… It wasn’t a person I could be in touch with anymore, to run it by them to ask for their opinion, and just not being able to get over the anxiety about that. So I figured out, after spending almost a year wanting to do this thing but not feeling confident about it… I instead wrote this story about a trip to Hawaii with Roman Muradov, which I could share with him. I felt much more confident doing that.

MOK: This process of isolation to connection—I know you’re a big Talking Heads fan—it reminds me of the journey that David Byrne’s protagonist goes through in [the documentary] Stop Making Sense. He starts out with a guitar and a tape box, talking about isolation, and in the end he’s surrounded by all these people and wildly singing and dancing.

FOSTER-DIMINO: And he wears a big suit [laughs]! My favorite sequence is Stop Making Sense is when he’s dancing with the lamp… very genuinely.

MOK: That’s a very Sex Fantasy moment.

FOSTER-DIMINO: I know, I think so too, I’m glad you think so! Just the idea of trying to reach out to someone, when you think that you’re not getting what they’re putting out. Is this movement of the lamp, or is it my movement inflicted on the lamp? Is the lamp moving it because I’m moving it? It’s very Sex Fantasy!