R Sikoryak’s Terms and Conditions manages to compress half a century’s worth of required comics reading into the span of 104 pages, while simultaneously tethering it to this specific moment in time by using the newly infamous iTunes Terms and Conditions. When I prepare to talk to R. I am baffled—how does someone prepare to talk to a figure who is clearly so incredibly knowledgeable in his field? Not only in its history, but in the grunt work of what really makes a comic work, visually and textually? What is there to ask other than, How does my brain become precisely like yours?

R Sikoryak’s Terms and Conditions manages to compress half a century’s worth of required comics reading into the span of 104 pages, while simultaneously tethering it to this specific moment in time by using the newly infamous iTunes Terms and Conditions. When I prepare to talk to R. I am baffled—how does someone prepare to talk to a figure who is clearly so incredibly knowledgeable in his field? Not only in its history, but in the grunt work of what really makes a comic work, visually and textually? What is there to ask other than, How does my brain become precisely like yours?

In his career, R. Sikoryak has parodied just about every significant cultural figure or reference you can think of: Beavis and Butt-Head, Regis Philbin, 12 Angry Men, the list goes on, alongside working at Raw Magazine right out of college, and now teaching at Parsons. Sikoryak’s parodies aren’t merely notable because of his ability to so flawlessly replicate the style of another, but because—through these well-executed drawings and scripts based on the works of others—he manages to leave his mark on it all. There’s something so distinctly Sikoryak-ian about Crime and Punishment as a Dick Sprang Batman comic. Or a Win Mortimer-inspired comic cover that finds Trump, in the midst of a battle with a nurse, upon finding the “cure for Obamacare.” Or even his New Yorker covers, wordless as they may be. No matter which work of his you’re reading, you’ll always see his stylistic signature there, peering from the corner.

Intrigued by Sikoryak’s Terms and Conditions, I spoke to him on the phone about making a book that is somehow like browsing the internet, how work affects one’s creative output, and thinking about the way work is consumed as you are making it.

Rachel Davies: What was the initial spur for the book?

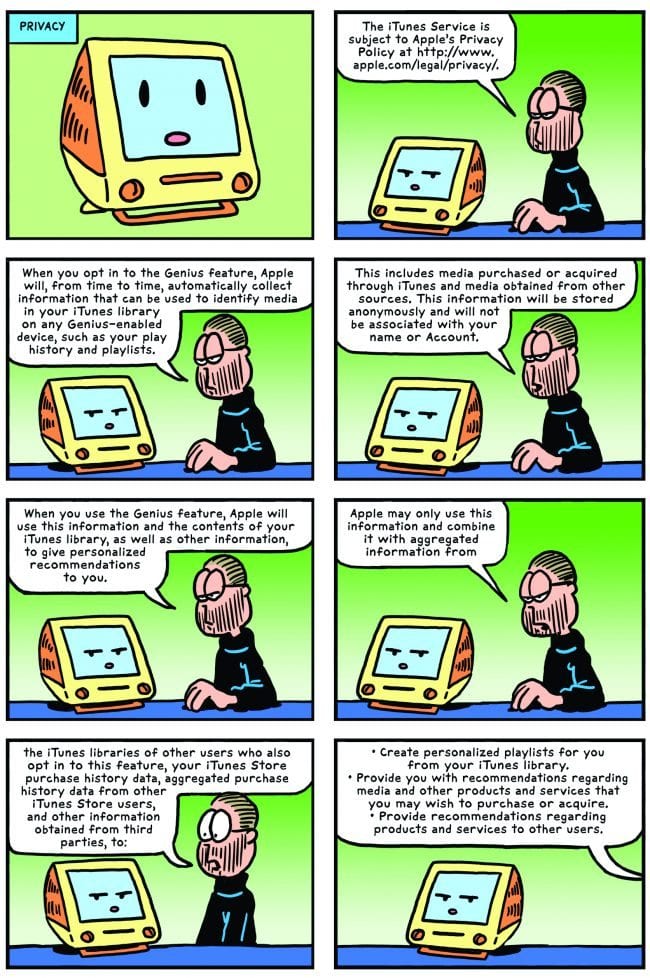

R Sikoryak: I was trying to find a new way to make comics without the editing and deconstructing side. You’ve probably seen my earlier stuff, it take long pieces of literature and boils them down into comics. so there’s lots of editing and consideration, and then combining it with the style and figuring out a way to replicate that style, and learning how to draw that way. So I just found that I had a very time-consuming approach to making comics and I was really interested, instead of spending a year on a ten page story, I was interested in seeing if I could do a longer graphic novel-length work. In casting about for what that would be (I always work with found text to one degree or another) I thought of a text that is famous for being long, and that’s the terms and conditions from iTunes. That seemed funny and silly enough for me to get behind doing.

Reading the book, I couldn't help but think that it must have been such a daunting task to track down all these comics that were precisely right for what you were attempting to convey with the material at hand. Were you ever hesitant about the project because of this?

Well, in some ways it was less daunting [than my previous works]. Because I try to adapt heavy, important works of literature, usually, like Crime and Punishment or Wuthering Heights, it sometimes gets daunting to struggle with a work that people are very familiar with, and that has characters that people really love. What was great about the Terms and Conditions for me was that there’s no narrative, and no one has an emotional attachment to it, at least not in the same way. I certainly don’t! It freed me up, it liberated me from having to worry about being faithful to it because there’s not a narrative to be faithful to. And it doesn’t lend itself to illustration in an overt way. I wasn’t interested in choosing a text that would be cinematic [laughs], I was interested in a text that didn’t have those concerns that I usually have when I’m doing a text. By choosing a text that had no narrative, it meant I could use the narratives of the comics that I was parodying to provide drama, or suspense, or humor. It was, in a way, a relief. I don’t know how I could do this again! [laughs] But for this project it was kind of a break from the way that I normally make comics. The length was daunting in a certain way, especially when the terms got longer as I was going, and I had to go back and revise them, and then add twenty more pages in the end. But that just gave me an opportunity to add more different styles, so in a way, ultimately I’m happy that they strung me along like that. In terms of me being daunted by it, it was a little overwhelming but I could see the end of it, I knew the end of the text. I knew there was an end. My only concern was that they were going to update them again, and I would have to update them again, but ultimately it was finite. It wasn’t as if I was writing an inter-generational family saga that took place on multiple planets or something—Oh, I have to take care of those people I introduced! So it was very different than something like that, you know, I wasn’t doing Dune.

When you were choosing comic pages to sample, were you trying to create a visual narrative from one page to the next or were you just worried about the narrative that was contained within each page?

Yeah, I was more concerned with the narrative that was contained within each page. I wanted there to be a character present throughout the page who I could sort of use as the protagonist, and he's dressed in Steve Jobs’s outfit. Beyond that, it was very up for grabs. I mostly chose pages for the purpose of having some sort of visual interest or narrative. as well as, Is this a famous artist that I’m parodying?, or Is this a famous character that I’m parodying? or Is this a famous comic strip that I’m parodying? So I was trying to kind of hit the points of interest in all of comics history, but I didn’t feel I needed to worry about the narrative from page to page, although you, as a reader, could make one out of it. I will say I chose the final page with text because I like the sunset as some acknowledgment that we’ve come to an end. Other than that, there’s very little in the book that has any connection, visually, to the text. Again, as a reader I think one would make that connection, but I didn’t feel like I needed to supply one more than was already provided by the great pages that I was working from.

Yeah, I found that reading it was a lot different than any other comic book because you do have to make a lot of those connections for yourself. Obviously when you’re reading a regular narrative comic book, it’ll show what they’re talking about and it’ll relate in some way, but reading Terms and Conditions was definitely a more intensive reading process. Were you thinking about what it would be like to read it at all when you were making it?

A little bit, I think I was just responding to—in a way, I wish I could read it. [laughs] I mean, I wish I could read it with fresh eyes, is what I’m saying. But in a way I was kind of responding to a trend that you sometimes see in educational comics where the visuals and the text really tell exactly the same story. Sometimes you can get a little impatient reading something like that because if someone’s talking about a chair, and then there’s a drawing of a person with a word balloon saying, This is a chair, and he’s pointing to a drawing of a chair--it gets a little tedious. I felt like the text let me step aside from that, and I didn’t get seduced by, Oh, that’s a really beautiful chair! I want to draw that chair. Since they’re talking about things on a rather abstract level I was able to avoid that. I’ve done readings of the strips as slideshows--that’s something I do with a lot of my comics--and people seemed to get caught up in the narrative that’s sort of there. But I don’t know what it’s like to see it entirely fresh. I’m trying to think of other comics that have done things like this… There was a Mad comic in the '50s where they took a comic and they rewrote all the dialogue, so that’s kind of happened before. Jason Little took an old romance comic, and completely rewrote the story. There’s probably an example very close to this, I don’t really believe in originality. [laughs] There’s probably something a lot like it, but I just don’t remember it. I certainly was inspired by Art Spiegelman’s early experimental comics in his book Breakdowns, and Breakdowns also has a parody in here, too. I felt like he was constantly trying to break the text away from the comics in interesting ways. Maybe not over so many pages, but I felt like he was making an effort to at least make you aware of that. Certain writers do it to a certain extent. I just can’t speak to how it reads. Like I said, I’ve reread it but there is an element of surprise that is lost on me.

With regard to your ability to replicate so many different drawing styles, what is your background in drawing? Have you always been doing parody drawings?

Oh, yeah! It’s funny, my brothers and I all collected comics and we would do parody comics even as kids. I was a big fan of Mad, so I was looking at humor comics from a really young age—I grew up in the '60s. That was always an interest to me, trying to replicate styles. I mean, I think all people start there, but I think I ended up there. I used to always worry about being derivative, unconsciously, or being like a second rate version of someone because I felt like I was inclined to pick up cliches or habits from other artists. I thought I might as well make that overt. Since I was in college, I got started on working this way and I’ve just done it so long, I’m rather methodical about it. At this point, my style is to just pick up as much as I can from other people, but do it in an overt way. That’s why there’s an index in the book, I wanted people to be conscious that it’s coming from specific places.

For sure! When you were choosing what you were drawing from, were those all comics that you had in a personal collection, or were already aware of, or did you seek out different thing that were out of your personal interest?

It started out being more artists that I either had examples of personally, or just popped in my head initially, by the middle to the end of the book, I was more interested in making sure I represented people that weren’t in my collection. Though my collection is fairly eclectic, it probably leans more toward historical comics, and contemporary comics, but I really, really wanted to include people like Kate Beaton, and Allie Brosh because I wanted to make sure I was representing a newer part of the comics universe. I mean, I have a lot of Kate Beaton in my collection, but I wanted to make sure I was covering a lot of bases. At a certain point I remember looking in the iTunes store to see what was popular in graphic novels, I just thought, What have I not gotten to? I think from that I ended up including the Transformers and My Little Pony, which is interesting because they’re both licensed comics, and licensed comics have always been a big part of comics, so that seemed like a valuable to include. The Walking Dead struck me early on—I haven’t read a lot of those comics, nothing against them I just don’t read a lot of horror comics—but I wanted to get that in there early because it’s something that is instantly recognizable, very iconic. It was a real mix. I wanted it to feel like the internet.

Yeah, I was thinking about that. I definitely noticed that, it was interesting reading it, and kind of feeling surprised by how much I knew. Like The Walking Dead, I have no connection that at all, really, and I got the reference. It makes sense, with the internet you see so many things unintentionally and then they’re part of your reference bank without any effort.

Yeah, and I like being surprised! I didn’t want to choose favorites. I tried to be very open minded about comics that are coming out. Comics that are popular are always fascinating to me -- like why did this connect to people? I don’t mean to judge why it’s popular, I just think it’s interesting what things really hit people, what strikes a nerve, and what connects. My work is in some ways really theoretical, and objective. I always kinda want to analyze what makes something work, and what makes something popular, which isn’t always the same thing but sometimes is absolutely the same thing.

What do you tend to read the most of, like historical stuff, older, or do you read more contemporary comics now?

What do you tend to read the most of, like historical stuff, older, or do you read more contemporary comics now?

It really depends on where I’m at. When I’m working on a project, I’m just reading the comic that I’m parodying. I did a Wonder Woman parody comic a couple years ago -- a retelling of the Marquis De Sade’s Justine in the style of a Wonder Woman comic so I was just reading 1940s Wonder Woman issues. So I’ll just sort of glom onto an artist or an era of a character, and I’ll just read all of the stuff I can. But I do try to keep track of what’s happening now in graphic novels, I really liked Riad Sattouf’s last book, I really liked Ulli Lust’s last book. I have to say Comixology, not to put another shoutout to an internet corporation, but Comixology has increased what I’ve been reading just because so much is available, and I don’t have room on my bookshelves anymore. [laughs] I do still have some room, I still buy some books. But I also buy a lot of digital comics because they’re so plentiful, and lighter.

You teach at Parsons, right? What do you do there? How do you think it figures into what you publish?

That’s really interesting! I teach in the illustration department, so depending on the year I may be teaching a different class. I’ve taught comics classes there, which is really interesting because I have students who aren’t necessarily comics makers but they like the idea of making comics, or they just want to try out something new. It’s fascinating to see people come from a very different angle than I would, or to find people who were reading a lot of comics… I feel like I had the same approach, where it’s like, I read a lot so I know how these work, and I can just sort of jump in and do it. I see that in students, and that’s always exciting.

Right now I teach a class called Senior Thesis: Each student gets to work on their own project, and some of them are making comics, some of them are making a series of paintings, some of them are making animated films—it’s all over the place. They all sort of get to choose the approach they take. One reason I like that class is because I can talk to them about their conceptual reasons for doing a project. If I don’t know how to make an animated stop motion film, or know how to use a specific computer program, I can still talk to them about aesthetics, or I can talk to them about approach, or I can talk to them about how [their project] works as a viewer. I’m really interested in that, and I feel like I can give them advice from that standpoint. Also, having just done this book, I feel like I can relate to them on working on a project that nobody asked them to do, but they are compelled to do. I hope I can teach them something about keeping deadlines, and I hope they can teach me about keeping deadlines, because I always feel like managing time is super-hard when you’re working on something that’s self-motivated, and that maybe you have never made before. I really love talking to the students, partially because it’s fresh for them, and partially because it’s often fresh for me, and their experience of art making is so different than mine. What they’ve seen, and what they bring to it. There’s a generational, I don't want to say divide, but difference that is really interesting.

Did you always know you wanted to make comics? When you went to school was that always your end game?

It was always my end game, but I went to school in the '80s, and that was actually a point at which I realized, or at least I felt, that I could make a better living doing freelance art and illustration for magazines. I went to school in New York, actually at Parsons. where I teach now, and the world of freelance editorial illustration was pretty broad. I certainly knew I wanted to make comics, but I felt like I’d have to make them in my spare time, and do other kinds of commercial art for a living. I fluctuate back and forth because I do get to do a lot of comics for commercial publishers, but it’s always sort of juggling the different parts of my career, or my different abilities for different jobs. I was always interested in making comics, and I was lucky enough to be introduced to Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly when I was in school. That helped me a lot because I was already really into Raw, and Art’s earlier experimental comics, but getting to meet them sort of got my foot into the door of a world of comics that totally changed my life. [laughs] That I was actually able to work with them was incredible, and I got so much out of that. I think I would have been making comics in any case, but getting to meet and work with them was really life-changing, and I’m sure really affected the kind of comics I make today, in a good way. I think they made me be more critical and rigorous in the way that I approach what I do.

RD: You worked at Raw right out of college, right? Were you in editorial, or were you just making comics for them?

RS: Well, it was such a small company! It was only Art, Françoise, and a few other freelance helpers in the office, and me. So it was really tiny! I was doing production work for them, I was packing boxes, shipping out books, I was doing office stuff, I would coordinate with artists to get work turned in. A lot of production work, a lot of different things in that way. They weren’t publishing that much, although they did publish a couple of my early comics, and I certainly think that I worked really hard because I wanted to make an impression in Raw. [laughs] It was a big deal for me to get in that magazine. They didn’t publish a lot of my work, but they taught me so much about production, design, and editing. I helped out wherever I could, I pitched in as was needed. It was a really interesting job because it just involved so many facets. It would have made me a great self publisher if I had had the stamina to do that. They taught me a lot about how to make work, and juggle that with freelance work, too! At that point Art Spiegelman was still at Topps designing bubble gum cards, and things like that, Wacky Packs, and all those series—some series I grew up with, even. I feel like I’ve always been working, everything I’ve been doing, has been there to help me make comics, in a way. That’s the goal, to make more comics, and there’s lots of things, peripheral or very related to that, that have kept me busy.

RD: Both of your most recent projects—Terms and Conditions, and the Unquotable Trump—were first realized online. How does your attitude toward a work change when transitioning it from the internet to something tangible?

RD: Both of your most recent projects—Terms and Conditions, and the Unquotable Trump—were first realized online. How does your attitude toward a work change when transitioning it from the internet to something tangible?

RS: It’s funny, they were first seen online, but the iTunes project started as a mini comic. I published the first two parts of the iTunes book in April 2015, and I published the second two parts, the finale of the iTunes book, in September 2015. I had been selling them at conventions, and I’d been distributing them a little bit online through a mini comics distributor called Birdcage Bottom, I had gotten them out a little bit and I showed the mini comics to Françoise Mouly, and she said, Oh, you should put these on Tumblr! I did that, and then I sent out an email to everyone I knew in the world, and said, I’m doing this thing! The minute I sent out that email, this was like 20 or 30 days after putting it on Tumblr, the day I sent that email, Boing Boing had done a story, NPR called me to do an interview, The Guardian, all these other places came in, and started writing about it. I tip my hat to Françoise for knowing enough about the internet to tell me to use it. I kind of like to know what my work is before I release it to the world, like the iTunes book, I put out the first mini comic after I’d finished the first half of it—I wanted to stake my claim to it, but I’d already done like 35 pages.

By the time I put it on Tumblr I was done, and I was really astounded by the response. I don’t know if it would have been more paralyzing to have seen all those people be very excited about it. It was a little startling to see how fast it clicked in with people. With the Trump book, again I made a mini comic, but this time I already knew I was going to start putting it on Tumblr. But I did make all of it, 16 pages, and I published the comic—published, I photocopied it, and then I put it on Tumblr. The response to that was so great that I was encouraged to make more. In this case, for Trump now [The Unquotable Trump], I’m making images, and posting them on Tumblr, and in some ways I’m certainly open to suggestions, people have [messaged me], Oh, you should do this or that! But most people don’t have it all thoroughly worked out, so you end up just having to do what you’re doing. I’m certainly keeping my ear open if anyone has any ideas. In the Trump case, I kind of have my approach, and I’ve mapped out where I’m going, but who knows what he’ll say tomorrow! He’s a different case because the iTunes thing is a living document, they do update it, but he’s a living human, and a volatile one, so I don’t know what he’s going to do next. I’m happy if he stops giving me material! I don’t need anymore, but we’ll see what happens. I have to admit, I’m really glad that Françoise suggested Tumblr to me, it’s definitely increased my visibility. I don’t know what I’ll do next online, but I might post my next project there. It is part of what comics are now, and I hadn’t embraced it before. I feel like the iTunes thing in a lot of ways has just made me think about how comics work, and how I can make comics in a new way. I also think that’s what I’m all about is thinking about comics, so it’s definitely achieved way more than I expected it would!