Kevin Pyle has had an interesting dual career in comics. He’s been making comics like Prison Town and has contributed to World War 3 Illustrated for more than two decades. But he’s also been writing and illustrating a number of brilliant graphic novels for young adults. I first met him years ago when he was making books like Blindspot, Katman, and Take What You Can Carry, which were the subjects of our conversations. In Take What You Can Carry for example, Pyle writes about a teenage shoplifter sentenced to work for the shop owner he robbed, an older Japanese-American who grew up in an internment camp. Katman manages to meld teenage angst, Jainism, art, and animal welfare.

Kevin Pyle has had an interesting dual career in comics. He’s been making comics like Prison Town and has contributed to World War 3 Illustrated for more than two decades. But he’s also been writing and illustrating a number of brilliant graphic novels for young adults. I first met him years ago when he was making books like Blindspot, Katman, and Take What You Can Carry, which were the subjects of our conversations. In Take What You Can Carry for example, Pyle writes about a teenage shoplifter sentenced to work for the shop owner he robbed, an older Japanese-American who grew up in an internment camp. Katman manages to meld teenage angst, Jainism, art, and animal welfare.

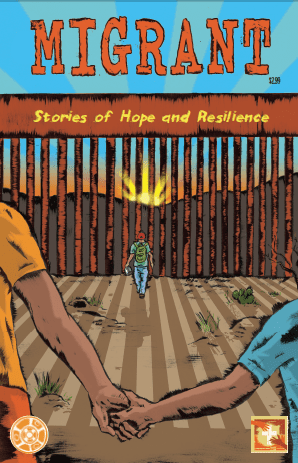

His most recent project is Migrant: Stories of Hope and Resilience. For a few years now, Pyle has been collaborating with writer and editor Jeffry Korgan on comics like Wage Theft, which are designed to be tools to help teach and illuminate people about social issues. Migrant is a 48 page comic printed in both English and Spanish, and a joint project with The Kino Border Initiative and Hope Border Institute, two Catholic social justice agencies. Pyle admits that the comic is educational, but he hopes that like most of his work, it’s about educating people, but it’s primarily about building empathy. Pyle continues to believe that opening people’s eyes to the truth of a situation can change hearts and minds and affect social change.

We’ve talked a few times over the years but how did you start out in comics? What were you reading when you were young that got you interested in doing this?

I didn’t actually read that many comics as a kid. I read Sgt. Rock because I was into everything World War II and I read Kirby’s Kamandi because the barber where I got my hair cut often had it so I’d buy issues to keep up with the story. I did read a lot of Mad Magazine – and a friend and I used to draw our own version called Crummy – but it wasn’t until college when I saw Raw magazine that I really started thinking about doing comics. It appealed to my own punk aesthetic at the time. Some things in the first issue I saw – number 5 – that got me really excited were Sue Coe, Pascal Doury’s Theodore Deathhead and a World War I strip by Tardi. Three very different things. My first comics were pretty absurdist, much closer to Doury than Tardi or Coe. That early stuff was printed in a xeroxed comic collection I co-edited, Hodags and Hodaddies, that came out once a month in 1990. We were the first folks to print Michael Kupperman, who did REALLY absurdist strips under the name P. Revess. We also printed a Ben Katchor piece, Indoor Cycling, which I’ve never seen anywhere else.

But that work is very different from what people might know me for – the young adult comics for Henry Holt, like Blindspot and Take What You Can Carry or the activist, journalistic things like Lab U.S.A. or Prison Town, which are also different from each other. The work I did for Henry Holt was informed by social justice ideas but not in a real upfront way. It all feels related to me but I’m not sure people see the connection, to the extent they even know my work at all.

What you’re doing in those books are telling these humanistic stories where characters are opened up to an awareness of new ideas and a larger context.

Those things were just what was floating in my mind and they found a way into the stories. In Take What You Can Carry, I was attracted to the shoplifting part of the story because I have this as my own experience with being caught shoplifting and instead of being incarcerated or having to go to juvenile court, somebody, the storeowner, decided that working in the store was a better way to approach the idea of punishment. The fact that he was Japanese and that I had a really great painting instructor in college, Roger Shimomura, who also happens to have been a child in the internment camps, sort of connected in the writing process. Those things came out of my own autobiography. I don’t close my mind to those things that I feel people should know or think more about, things that might be deemed political, but I don’t actively seek them out for those particular books either. They are themes and approaches that seem to assert themselves. I don’t know. [laughs] It’s hard to separate sometimes.

Those things were just what was floating in my mind and they found a way into the stories. In Take What You Can Carry, I was attracted to the shoplifting part of the story because I have this as my own experience with being caught shoplifting and instead of being incarcerated or having to go to juvenile court, somebody, the storeowner, decided that working in the store was a better way to approach the idea of punishment. The fact that he was Japanese and that I had a really great painting instructor in college, Roger Shimomura, who also happens to have been a child in the internment camps, sort of connected in the writing process. Those things came out of my own autobiography. I don’t close my mind to those things that I feel people should know or think more about, things that might be deemed political, but I don’t actively seek them out for those particular books either. They are themes and approaches that seem to assert themselves. I don’t know. [laughs] It’s hard to separate sometimes.

How did you end up connecting with WW3 Illustrated?

I’d seen it when I was in school in Kansas and I responded to the material. When I came to New York I lived in Williamsburg in 1988 and I sought them out. I met Scott Cunningham and some of the other WW3 folks when Scott curated a small press convention at Minor Injury gallery in Brooklyn. The work I first started doing for them was this Bertolt Brecht kind of Threepenny Opera thing, The Odious Omnivore, who would eat and crap all over everything. It was this over the top despotic capitalist, which in some ways was my idea of what should be in World War 3. It took a little while for me to decide that the journalism-based work was really more important to me. World War 3 has been really important for me in providing deadlines throughout the years and knowing I would have a place to publish material, I think, was really helpful for keeping me going.

You’ve edited and co-edited a few issues over the years.

I did a bunch of issues starting in the early '90s. I co-edited a prison issue with Scott Cunningham in ’94. I lived in Philadelphia for a while and then when I came back [to New York] I did some issues as well. I did a wordless issue with Peter [Kuper]. For a while I was the only person who could do computer production. [laughs] So I didn’t necessarily edit, but I touched every issue design-wise and I was pretty involved because nobody else knew how to do that until we got a younger generation of people in. I think we were one of the last magazines that was still doing cut and paste and visiting the printer in Queens to look at negatives. [laughs] So I’ve had a long history with them. In the next issue they’ll be printing an excerpt from Migrant. I feel very strongly connected to them even though I don’t get to edit as much as I used to.

You mentioned you edited a prison issue in the 1990s and Prison Town is about a decade old now. How did you get interested in these issues?

In some ways it has to do with the story told in Take What You Can Carry. When I got caught shoplifting, my dad had the idea that we should spend an hour or two in the jail before we left. [laughs] That experience may have made me think about those issues as I feel I’ve been pretty aware of my own white privilege and what the influence of that on my own trajectory was versus what it might have been for someone else under different economic and racial circumstances. It’s something I was always aware of. A theme that runs through all my work is that of the individual versus society and the I think prison is the ultimate expression of that. Lab USA gets at that. Society has certain rules they need to enforce and they do it in a very clumsy manner – at times in a very unfair manner. How individuals get ground up by institutions has been a focus of a lot of my work and I think prison is a real expression of that.

In some ways it has to do with the story told in Take What You Can Carry. When I got caught shoplifting, my dad had the idea that we should spend an hour or two in the jail before we left. [laughs] That experience may have made me think about those issues as I feel I’ve been pretty aware of my own white privilege and what the influence of that on my own trajectory was versus what it might have been for someone else under different economic and racial circumstances. It’s something I was always aware of. A theme that runs through all my work is that of the individual versus society and the I think prison is the ultimate expression of that. Lab USA gets at that. Society has certain rules they need to enforce and they do it in a very clumsy manner – at times in a very unfair manner. How individuals get ground up by institutions has been a focus of a lot of my work and I think prison is a real expression of that.

I would also say that a driving force of a lot of my political work is the belief in the goodness of people. If they know the situation, if they know the abuses of the system, they will actually do something to change it. People do that. I think one of the problems with prisons is how people don’t want to think about these things and they push it out of their heads. I think comics have a unique way of engaging people and reaching people on these difficult issues. Somewhere along the lines I came across this idea that for a certain segment of the population, racism is a failure of imagination. A failure to really be able to understand and empathize with the experiences of people different than oneself. Some of this work is about trying to visualize that. Especially in Migrant we’re trying to connect people to people on a basic human level.

You mentioned when we were setting this up that Migrant and Wage Theft came about through your friend Jeff Korgen who wrote the books. How did you two connect?

I met Jeffry at a party. He asked, so what do you do, and I said, I do comics. He said, I love comics, are you Marvel or DC!? I’m like, well, that’s not really the type of comic I do. I’m doing comics about social justice issues. He said, I love social justice! I’m a big social justice Catholic! He was writing books about globalization and I talked to him about Prison Town, and how successful that had been as an outreach tool. Months later he reached out and said, I have this great idea. He had written nonfiction and he said, I would love to try my hand at writing comics and there are these progressive Catholic organizations that are interested in getting these issues out in front of people. So these projects really came out of his being inspired by Prison Time and by that model. This idea that this tool may be more effective than pamphlets and policy papers and things like that.

I thought Wage Theft would be a one time thing, but our partnership has been an ongoing project. He raises the funding so we can go to places like Houston and interview people who were victims of wage theft or to Arkansas to talk with people working in the meat processing plant about health and safety issues. Most recently in Migrant we were down in Juarez and Nogales with these very dedicated social justice activist groups who are helping asylum seekers and recently deported people. To sit down with the people trying to escape violence in El Salvador and Guatemala and hear their stories is such a powerful experience. The process has been really fascinating and it gives me a real sense of responsibility to produce these comics. The way these comics get used by these activist groups in some ways really reaches that World War 3 ideal of trying to have art function in this activist way. These projects have been very satisfying on that level.

As an artist and a storyteller, this is a short project, it’s supposed to be straightforward, it’s going to be translated. You’re not a really experimental artist but you do have to simplify in a project like this.

In some ways it’s helpful that I have a cowriter. Jeff writes the first draft and he’s very good at thinking about what information we really want the potential reader for these to get. It can be very challenging to get all the important aspects included in a 24 page comic. We really want to expand Migrant and try to have another shot at this material because the page limit and the demands of the project do limit your storytelling possibilities quite a bit. Even though they’re pretty straightforward stories, one thing that really excited me about Katman and Take What You Can Carry and Blindspot was the formal experimentation that I could do with color and different styles or interweaving stories. You do have to give that up for something like this. I think if we get to expand Migrant we can do some different storytelling. It’s also frustrating to do so many interviews and have so much great material and have to boil it down to such brief storytelling.

You and Jeffry went to Juarez and Nogales and talked with migrants and activists and this was a very involved project.

You and Jeffry went to Juarez and Nogales and talked with migrants and activists and this was a very involved project.

It was. We interviewed close to thirty or more people in shelters, soup kitchens and community centers on both sides of the border. Plus Dreamers and the activists themselves. We also saw this very surreal yet to be occupied processing center on the border forty miles out of El Paso. It was all made out of huge convention tents and they had clothes and shoes for the families that would be there. We were there with a bunch of advocacy groups and there were military people video taping us as we walked around. It had a very creepy X-Files vibe. On another afternoon in Juarez we had to cancel some interviews because there was a bunch of shooting in the area. So my own inclination would maybe be to try to tell these stories the way Joe Sacco might or the way Sarah Glidden did, where part of the story is where you’re in it, but that’s not really the intention of this project. With Migrant we had to make a lot of decisions to tell stories that would explain the human dimensions of what’s going on down there and what these people are experiencing rather than talking too deeply about the experience or current policy that might change before the comic came out. Comics done in partnership with multiple activist partners can not be as agile and quick as one would like. [laughs] I was able to get it out in two months but things are changing so quickly. We did our interviews right after Trump was elected but before he was inaugurated so it’s very difficult to know what the effect is really going to be. Also the way this administration makes pronouncements or memos but then it’s never really codified into official policy makes it difficult to report on. It’s very difficult to know what’s actually happening right now. Especially in places like the detention centers, most of which are privately run. We really won’t know what’s happening in them for a little while. It’ll take a little while to separate fact from fiction and fact from anecdote. The groups down there know what’s happening, but what’s happening in one instance is different from what is the actual policy.

And as you make clear, there are a lot of unwritten rules and gray areas and it’s hard to know what the policy is in practical terms.

When I was doing work about the prison system I would talk to prison activists and they would talk about how there are black and white rules, but then a bunch of rules aren’t enforced regularly. Their belief is that the reason the prison doesn’t enforce them is because then they become a coercive tool. Because when you do enforce them you have some power. The things that are unwritten and left un-codified give much more wiggle room for doing whatever the hell you want. Or, keeping the people who are affected by these policies off guard so they don’t really know what’s happening. This is true in with the immigration issue as well.There’s a huge climate of fear especially among the dreamer kids who were brought here at five or eight years old and don’t really have any memory of living elsewhere. They are living right now under such a shadow of fear because tomorrow they could get rounded up and be sent somewhere where they don’t know anyone or even speak the language. Plus, under DACE, they gave all their information to the government.

The comic is mostly people’s stories. What was the initial plan that you and Jeffry had when you went down.

We made a list of issues that we really wanted to focus on – and that list was much bigger than we could totally approach in the comic – but it was our guide for editing what came up in the interviews. Except for some of the history and policy stuff, almost every word balloon comes from an interview text. The content was very much driven by what we got from the interviews. Then there also were touchstones. We wanted to explain what happens when you get picked up at the border, and what are the two or three possibilities of where you may end up. Or how the population of people crossing the border has changed. At one point it was economic migrants who by policy were encouraged to come and go freely because their labor was needed, whereas now it is primarily asylum seekers fleeing violence in Central America. There were elements like that, basic things we thought the uninitiated reader should know about what the situation is. That also formulated our questions that we would ask of the different people we interviewed.

I know something about this but then I read things in Migrant like how ICE is required to have a certain number of detention beds, and most of it is private prisons.

It’s interesting because that’s the stuff I get really excited about. I get excited about all of it, but I do think there are policy things like that which are really unbelievable and illuminating which should be included. The bed quota came up in trying to explain how the detention system works and how it intersects with the profit motive.That whole flow chart was interesting because when we were talking to activist groups down there they said “we want something about all the places where you might go when you get picked up because we can barely keep track of it ourselves.” It was only two pages, but it was surprisingly hard to really pin it down in a way that would come across to the reader because it’s very complicated. That’s one of the things that probably has changed. Certainly in terms of numbers.

We were talking about simplifying and I hate thinking of these comics as “educational” but they are tools.

Yes, but I do hope that one of the results of the comic is that by seeing the human faces of the people affected by this and hearing their stories, that the reader feels a little bit of what it would be like to be this kid Ricardo who’s fourteen years old and travels all the way up from El Salvador with his little brother and what it’s like to be reunited with his mom. Or the mom who can’t see her daughter because she’s been deported after living in America for years but her daughter is a citizen and needs to be in America for her health treatment. It’s educational, but I hope it’s more empathy building.

Not just a name or quotation in a news story but a face and a story.

Exactly. Any of these stories could have been five pages longer. If we can get a publisher for a larger book we’ll be able to expand some of these stories. There is a push and pull between the details that you sometimes have to leave out because you’ve only got five or six panels, but sometimes it’s the details connect people to someone.

You put Migrant together in collaboration with two NGO’s. What was that like?

We sent them everything and their only feedback was, is the stuff accurate? They were really comfortable with the way we told the story, but they were indispensable to the process. They set up the interviews. One of the groups we worked with, Kino Border Initiative, have a comedor which is right across the border in Nogales. People who were just recently deported get dropped off across the border and they might not even be from Nogales. In fact there’s a policy that they try to drop people off in a different place from where they came from to discourage re-crossing. There’s an idea that it may break up criminal networks that way, but a lot of people don’t have knowledge as to how to get back right away or have any way to connect with family because they’re in a completely different place. So these people were dropped off or maybe they were trying to cross and they were in the desert for four days and they come to this comedor to get a meal and a place to sleep. These activist groups have established trust with them and I’m sure we would not have been able to achieve this without those institutions and that trust that they’re already established to interview these different folks and to have access to them. They were indispensable in that sense. I wouldn’t say they in any way shaped the narrative except from the stand point of saying it would be good to mention this and that would make the piece more accurate. Things like that.

What is their plan for how they’re going to use the comic?

One of the organizations, Kino, is going to be using it in Jesuit high schools as a way to get their students to better understand the scope of what’s going on there. Hope Border Institute is in some ways the conduit to other organizations. A lot of college groups will come down to the border to really understand what’s happening and this will be given to them as something to take back. There were some UCLA students down there that we walked with around the area of the desert where people cross near Nogales and their excitement about the idea of this comic was palpable. They were excited about that as a strategy compared to other approaches. NPR in Arizona did a story on it. The novelty of it being a comic, those of us in the graphic novel world are tired of that angle on a story, but in this context it’s very helpful. It gives local news outlets another way to talk about this issue. One of the hardest things for these activist groups is getting people to continue to focus on these issues and so this is another hook that helps them stay out there and engage with the media.

Where did the idea of ending with the posada come from?

That came from my co-writer, Jeffry Korgen, who as I said is a social justice Catholic, and these two groups we worked with are Catholic. The majority of people crossing the border from Central and South America are Catholic, or at least a large amount of them. We were in Nogales when they did this posada. The posada is a traditional Mexican ceremony but down in Nogales they’ve tied it to the experience of the migrant, which is a perfect metaphor that’s awful hard to ignore. Given who the targeted group of people is and who the activist organizations are it seemed like a good ending as a way to hit that metaphor home.

It ends perfectly but I can’t help but think that it’s not a story you would not have necessarily happened upon if you were working with a secular group.

That’s true. But these are powerful stories and they have a long history and it’s interesting to make that connection. I think it’s a great connection to make. The best stories are sometimes the ones you find by accident.

Migrant came out a few months ago?

It came out in late May but Jeff and I are going to try and do some events in the fall to give it another push. It’s so pressing at the moment and we want people to connect to it. The activist groups have their uses for it and that’s ongoing. It’s interesting too because I feel like they just have so much on their plate currently because so many things are changing so quickly. Situations that they haven’t had to deal with in the past. For instance there’s a group down there, Humane Borders that’s mentioned in the comic that has had an aid station in the desert for I don’t know how long, helping people lost in the desert, providing medical help. Recently ICE for the first time ever raided the emergency station. It’s always been left alone under the international human rights idea that medical care is sort of a base level of humanity. It was raided and they had to shut down. Situations like that which have never happened before are happening and so I’m not sure how much the groups down there have been using [the comic] but I don’t think they can push it as much as Jeff and I can at this point. So we’re hoping to get it out there.

And hoping to start on a bigger book around these issues and stories.

We are working on proposals to expand the project. There are a lot of environmental issues down there. The fact that down in Nogales you’ve got the Native American reservation and they have their own ideas about what should be done with their border and what kinds of conflicts that could cause. Also updating what is now happening with ICE. The privatization of detention centers, the expanded raids and more aggressive tactics like picking up people in court etc. Things like that need a real spotlight on them. I think the idea for the larger project is it would be more a portrait of the border. All of this material would find its way in there and all the research we’ve done, but also a portrait of the place. Artistically I’ve always drawn a lot on a sense of place for my own work so I’m excited about approaching the material form that standpoint. It’s such an evocative place.