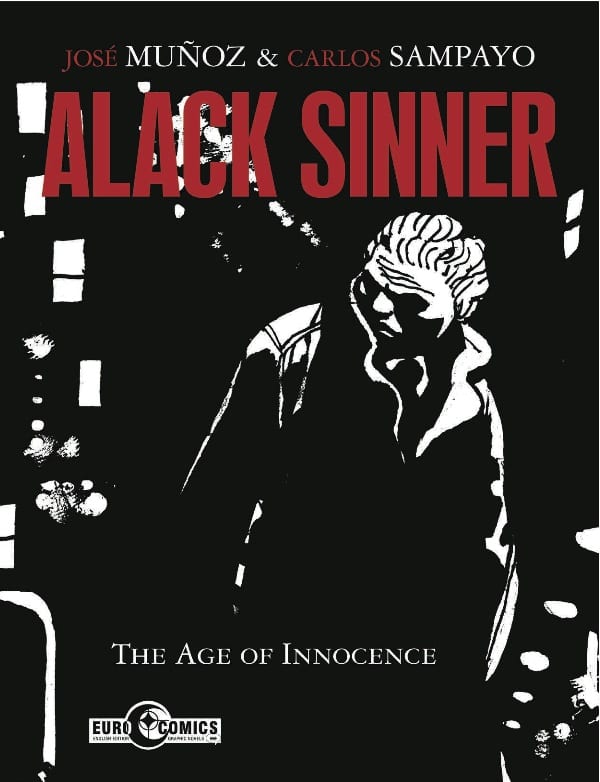

It is not hyperbole to say that José Antonio Muñoz is one of the most important and most talented cartoonists alive today. The Argentinian-born artist has received awards and accolades from around the globe including the Grand Prix de la ville d’Angouleme in 2007. Sadly too little of his work has been available in the United States, but this year two books have co1me out from two different publishers. IDW’s EuroComics imprint is releasing the first of two volumes collecting all of the Alack Sinner stories that Munoz made his longtime collaborator Carlos Sampayo. NBM is publishing another collaboration by the two, Billie Holliday, which is less a straight forward biography of the legendary singer as it is a meditation on her work, her life and her influence.

It is not hyperbole to say that José Antonio Muñoz is one of the most important and most talented cartoonists alive today. The Argentinian-born artist has received awards and accolades from around the globe including the Grand Prix de la ville d’Angouleme in 2007. Sadly too little of his work has been available in the United States, but this year two books have co1me out from two different publishers. IDW’s EuroComics imprint is releasing the first of two volumes collecting all of the Alack Sinner stories that Munoz made his longtime collaborator Carlos Sampayo. NBM is publishing another collaboration by the two, Billie Holliday, which is less a straight forward biography of the legendary singer as it is a meditation on her work, her life and her influence.

Looking at Muñoz’s life and artwork it’s possible to see some the global conversation around art and comics and literature of recent decades. Munoz is from Argentina where he studied under Alberto Breccia, worked with Héctor Germán Oesterheld and Francisco Solano López, and is part of a generation of creators, who, like Oscar Zàrate, fled for Europe. Reading his pages, it’s possible to see how he’s influenced so many creators from the generations that followed. Muñoz’s work is heavily stylized and yet it takes place in a realistic setting, not a fantasy world as so many of those who were influenced by his style have done. As he makes clear, he thinks about art and the world in political and philosophical terms, and that perspective can be found in many of his stories.

We spoke over e-mail with the help of a translator. Many thanks to Stefan and the team at NBM for arranging this.

Note on the translation: Muñoz prefers to use the Spanish word “historietas” which encompasses comics, graphic novels, sequential art, and that word is used here.

Alex Dueben: When did you want to be an artist? And when did you want to draw comics?

José Muñoz: In my earliest memories my desire to draw is already there, or I’m drawing, or there are drawings that I can still see in my mind’s eye. I felt, even back in my most primal and pivotal memories, that I like to draw. Much later, already on the path of historietas, my encounters with the drawings of Vincent Van Gogh, with Humberto Cerantonio’s work and lessons, with Hugo Pratt’s drawings, with Alberto Breccia’s drawings (to me they are a diurnal and a nocturnal expressionist) and lessons and the drawings of Solano and Roume, plus a long, long list of artistic excitements, enlightened me, helped me discover, feel, and think artistically.

You studied at Escuela Panamericana de Arte, where Hugo Pratt and Alberto Breccia taught. What was your art education like? What were Pratt and Breccia like as teachers?

My art education was a bit complicated: nearly simultaneously I started to study drawing, painting, and sculpture with Cerantonio and drawing with Breccia. I showed Cerantonio my historieta drawings and he didn’t like that strong desire of mine at all. He thought that I deserved a “higher brow” and more socially accepted way of expressing myself. I burned this idea into my mind and thus, for many years, I hid my enrollment in courses taught by Breccia at the Escuela Panamericana de Arte. Two parallel lives. “Clandestine Comic Blues.” Breccia knew about Cerantonio, but Cerantonio did not know about Breccia. I never studied directly with Pratt; I just studied and continue to study on my own his striking soulful work. They each gave me so much.

Besides your formal education, you were an assistant to Francisco Solano López. What was he working on at the time you were doing that?

It was 1958, I was 15 or 16 years old. Solano, what a wonderful person – as a draftsman he had Buenos Aires in his hands. He drew such warm, realistic, ethnic human faces looking to you directly from the frames. Obviously it takes time for me to understand that. His work was warm, emotional and deep. He was working on “El Eternauta,” “Amapola Negra,” “Rul de la Luna,” “Rolo Montes,” “Ernie Pike,” “El Cuaderno Rojo de Ernie Pike,” and “Joe Zonda,” all from Héctor Oesterheld’s scripts.

You went on to collaborate with the late great Héctor Germán Oesterheld yourself on Ernie Pike. What was your relationship with him like and what was it like working with him?

He was a kind of sportsman type, he played tennis and went rowing, timid and silent. He was always eating Mantecol [a typical Argentine soft, peanut nougat candy], often writing at his desk or talking into a magnetophone audio recorder. He was a gifted narrator of the human condition, producing thick, living stories based everywhere in the universe. He was a big reader and writer.

I met him at Editorial Frontera’s offices, when I brought, twice a week, the Solano Lòpez originals. He became interested in my drawings and around when I was seventeen, came to me with a proposal for a short Ernie Pike story, “Mozart.” Working with him –for him – gave me the sensation of being in old Hollywood, in black and white, as if I was entering a film.

What was the comics scene like in Argentina in this period in the 1950s and early '60s? You were there with all these people I’ve already mentioned along with Oscar Zàrate and so many others. From reading about it, it feels like this was a really creative and dynamic time.

Yes, it was a paradise. There were different languages, backgrounds, cultural viewpoints that were circulating around and trading funny and/or tragic stories with each other. The stories mixed together fluidly, spontaneously, through films, historietas, literature, and radio. There, reality and imaginative fiction and other fantastical stories came together to produce an intimate mix that, it seems to me, encouraged us greatly. We lived near, and in, the wide open spaces of the Argentine pampa lowlands, something that needed us to fill it with stories. I and others believed that everything that we read, watched, and listened to was happening to us, was happening there. Parallel realities leapt out from the pages and the screens into our surroundings, into our souls. Argentina tried, but did not fully succeed, in making immigrants forget their pasts. And Buenos Aires was infused with a cosmopolitan atmosphere; we were and we could be, anywhere. Calé, Arlt, Ferro, Borges, Solano López, Hudson, Dickens, Bradbury, Monicelli, Bergman, Bioy Casares, Oesterheld, Breccia, Pratt, Roume, Chandler – they all spoke to us of Buenos Aires, of Argentina, and of the world that surrounded us from the pampa to Irkutsk, being everywhere all at once. I suppose it was the same in New York. I imagine it that way as well, feverish.

How did you first meet Carlos Sampayo? Did you know each other in Argentina or did you only meet in Europe?

We met each other in 1971, at the Buenos Aires airport, saying goodbye to Oscar Zárate. But when we found out that we would be working with each other on tragicomics, we were already in Europe, during the long, hot summer of 1974, the last summer of the big Spanish “superhero” Generalissimo Franco’s era, on the coast of Catalonia.

Where did Alack Sinner come from?

Ahh, let’s see, as my mother used to say – from life and history itself, also from films, historietas, literature, and from Poe, Hammett, Chandler. Their narratives were born out of English-speaking empires when their desires for control and greed, as usual, led them to fall in with criminal organizations, giving birth to many little “Caesar’s empires” of organized crime in politics nearly everywhere. It’s a very common problem for us. Also it came from the investigative process outside and inside of us, from looking into society’s body and soul, at the many wounds. Lately I have started to feel that they are perennial, without falling into them – it’s so dark, be careful. We can express our impressions of them, denouncing them through narratives and art.

Were you always interested in crime stories? What did you read or watch?

Well, from my side, during my adolescence and early youth, we – Oscar Zárate and myself – lived mainly in the cinemas watching many international films, looking at and reading historietas, books—but never as many as Carlos Sampayo— always being in a lot of high, middle and low tragicomic narratives with words and images, only with words, only with silent or isolated images, sometimes falling down into a word that could be read as a constellation of meanings. I was interested in shapes, cities, white lights and black blacks, fog. Gifted German and Middle Europeans people arrived in the USA escaping from Hitler’s madness and, with their darker expressionist mood, aggravated the light and shadows of Hollywood’s minds. This cruel world enriches our figurative, narrative talents with the lack of meaning of the script of life. At that time the USA saved those people; many, many thanks, truly. Your country, you also, saved them, and they gave you their talents.

In South America we have nothing to thank your military-industrial politics for, nothing at all. Instead, we have been systematically molested by the imperial programs, ignorance, and paranoias of the United States. In my late twenties, coming from politics, before the organized South American killing of lives and hope — Allende, Pinochet, Kissinger the killer, Videla, etc — I began to focus my horrified interest on crime stories because they look just like reality. And, now with some distance, I could say that for the same reason, this too has led to my horrified lack of interest today.

The series changed – and expanded as you made the Joe’s Bar stories – and I feel as though it became more a vehicle to tell the stories of individuals. Was that always what you were primarily interested in?

The series changed – and expanded as you made the Joe’s Bar stories – and I feel as though it became more a vehicle to tell the stories of individuals. Was that always what you were primarily interested in?

This is a work in which you could create individuals, and where it’s possible to believe in them. At that time we went to Joe’s in a hurry to escape from Alack’s individuality, you see? Breathe, breathe, Alack, deep breath in between, into the others, hey Alack, do me a favor, please. Alack, Sophie, Enfer, Martínez, Cheryl, and all the crowd of timid draftsmen, moral morons, lost in translation, vocational dictators, dancing young souls waiting for true love, out-of-work killers, not so innocent victims from North, Central, and South America. That crowd went deepening into us, day after day. People, affection, drawing words, writing splashes, high-in-the-sky feeling moments, notable failures, and on and on. All that came from our friendship, from our work together.

Those characters, people, living in our pages, minds, and hearts during the seventies, eighties, nineties, and storms of indifferent cruelty, killings, depressions…greed makes law again, my friends! Then some of these characters went back to our souls, maybe to be protected. We were touched, inhabited, disquieted, and enthusiastic. Lately, I saw this: we arrived to construct, feel, write and draw to tell to you people from the USA good stories based in your circumstances and imaginations, made of our sentiments, ideas, lectures, limits.

It’s rare, actually, in historietas, I can’t remember any other cases. Shouldn’t be, but it’s quite rare. Generally, the empire tells — often badly, to say the least — the stories of disadvantaged groups to them.

That interest and concern for individual lives seems at the heart of your work, and especially the work that you and Sampayo made together. Where did it come from? Because that seems to be somewhat atypical in comics when you started?

That interest and concern for individual lives seems at the heart of your work, and especially the work that you and Sampayo made together. Where did it come from? Because that seems to be somewhat atypical in comics when you started?

Most of the comics at that time lacked real tragic desperation. And that’s ok, like some other necessary inventions in culture area, they were created also to channel it and forget it. In our case, desperation helps us a lot – We nearly killed the comics “bizznizz.” But I like and I need to channel and forget, too. Oesterheld’s writings, in his comprehensive, warm, deep way of looking at our problems gave rise to deeply human characters, and had more space for hope. Maybe in the forties and fifties hope was well placed in our lands. Some Argentine adults from back then say to me, you must be glad to have been be a boy during the time of Perón. But Oesterheld was an adult. Was he lying? Being together is so complicated, sometimes it looks like we’re just terrorized ferocious beasts galloping in eternal stampedes through the millennia. There is always a dark, cruel area between socialism and the various kinds of populism. We saw that during the last century, and today it looks even crueler because we are walking without a script.

How do the two of you work together? I imagine that it’s a much closer and more collaborative process than many writer-artist teams.

We talked, we listened to each other, we laughed, we scared ourselves, we surprised each other with what we said, with what we discovered there, trembling like leaves when we finally made or found a face, a perfect look, a narrative thread, even a single word, or a silence that lived. Listening to ourselves talk, we traveled south, knitting together possible narratives between New York and Buenos Aires. None of them worked. But those two cities, given life by the ocean and also partly cosmopolitan, partly American, and partly pretentious, for ourselves the cities work well. Other times things leave, they walk up and down, following maps, seeking a destination in the Americas—if there still are any—seeking to find that bar again, to find that corner, that girl, that particular one, with whom we still don’t know what language to speak.

You’ve both worked with others over the years, how do you and Sampayo decide to work together?

So we could return to the ecstasy of our work together where, sometimes, everything seemed to come alive, breathe, and think.

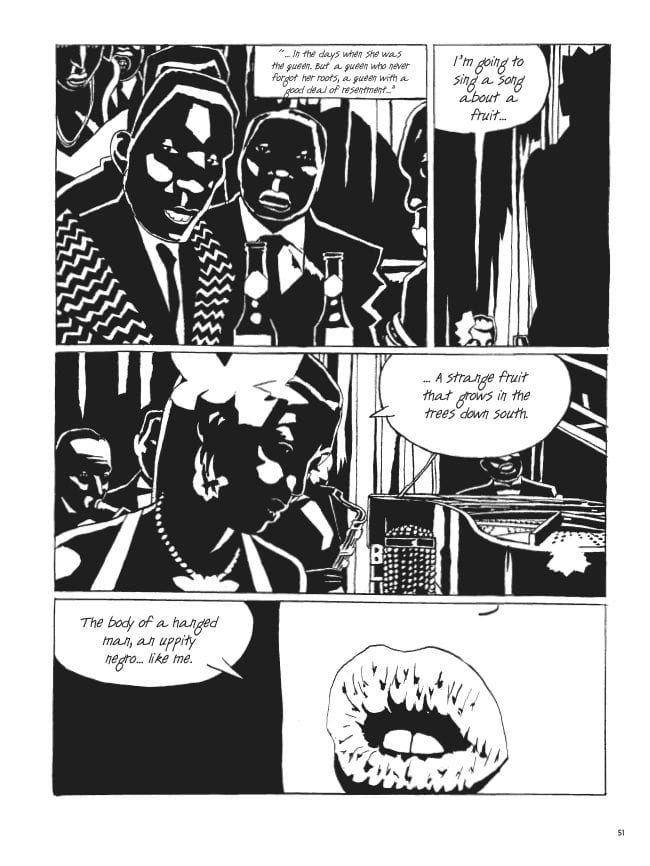

The biography of Billie Holiday that you and Sampayo made is coming out again here in the U.S. I wondered if you could talk about what the two of you were trying to do with this book? Because it’s not a straight forward biography, but a book about her and a tribute to her and her music more than anything. At least that’s how I read it.

The biography of Billie Holiday that you and Sampayo made is coming out again here in the U.S. I wondered if you could talk about what the two of you were trying to do with this book? Because it’s not a straight forward biography, but a book about her and a tribute to her and her music more than anything. At least that’s how I read it.

Yes, we could say that it’s always the same wind that blows inside you, some kind of jazzy hot Viento Norte with warm excitement and admiration mixed up together. We started playing around with that admiration, creating an autobiography as an act of creating an homage to her, the way it happens in real homages. We grateful people from the Southern tip of the Americas were blown away by Billie’s heavenly excellence. We said and felt that her voice became a voice for many other people. Fifteen years later, playing, writing and drawing about Carlos Gardel made us feel that way once more, he became another voice for all of us, and the Billie was still there, with the sun behind her. I have a snapshot in my mind: Buenos Aires, 1933, Billie and Carlitos singing in the central patio, the grapevine patio of my maternal grandfather Antonio’s house in Villa del Parque. I keep Gardel’s sheet music near Billie’s, a northern Black girl with a southern White boy. “America’s Ups & Downs: Original Tango and Creole Jazz Band” – that sounds good to me.

I’m guessing after reading the book that you’re both jazz fans. Could you talk a little about how jazz influenced your work, both on the Billie Holiday book, but in other books as well.

I’m guessing after reading the book that you’re both jazz fans. Could you talk a little about how jazz influenced your work, both on the Billie Holiday book, but in other books as well.

Hot jazz was a big early impression, as strong as the tango for me, maybe it impressed me more because it was exotic, foreign. I liked its energy, inventiveness, crying and laughing sounds, humor, the sounds of the vinyl and worn down record needles. In the Blues, the depth of the sadness sung by such extraordinary broken voices, like in Arab music, and in Flamenco and Fadò. I also really liked the urban environments that gave rise to the big bands of the 1930s and 40s, the beauty of the arrangements and some of the lyrics. The 40s were also a golden era for tango orchestras, singers and dance halls. Later Carlos Sampayo taught me more about jazz universes, groups, and feelings of the 1950s, '60s, and '70s and the contributions of black people to the swing and depth of the indigenous and white music of all of the Americas. They treated black people so badly while black people enhanced all of the music that they found. That’s a successful one sided dialogue, Chapeau.

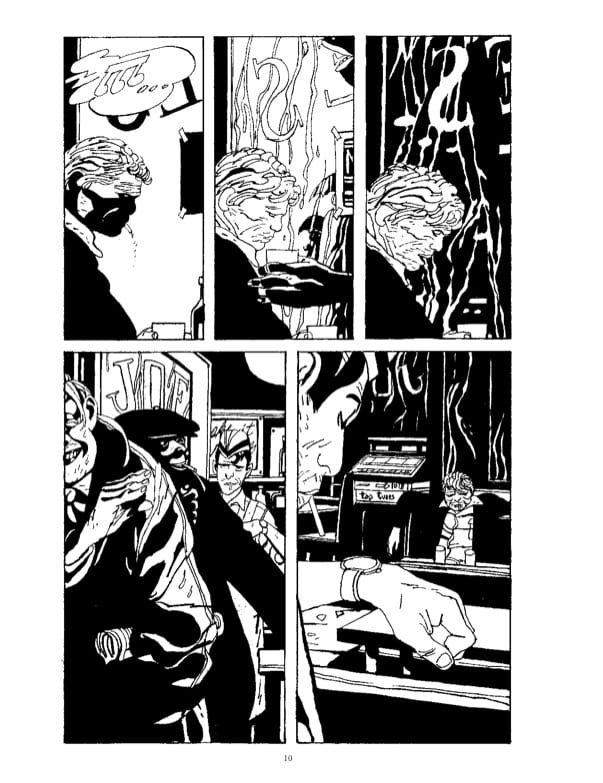

What is it about black and white work that fascinates you? Have you done any work in color? Are you interested in working with color?

What is it about black and white work that fascinates you? Have you done any work in color? Are you interested in working with color?

I like the nerves, the gesture, the energy of the manual blurring that we can make appear between light and shadow, on the border between them where they are always collaborating and discussing the limits. Both the shadow and the light excite me, differently. Most of the few other color works that I have made are linked to Buenos Aires, to tango and to my barrios. I also created work about Argentine places, feelings, and climates with black and white, but in color I’ve done Carnet Argentine, Orillas de Buenos Aires! and La Pampa y Buenos Aires, images and texts my own, and also a book, Encres with abstract and figurative images, as some kind of naissance of the planet through sequential art, made in watercolors.

What are you working on now?

I finished a black and white project, both drawings and texts, not a historieta, called Barrio adentro about dreamingly remembered atmospheres, houses, streets, and people of my intimate Buenos Aires barrios. The writer is Alejandro Garcìa Schnetzer.

I’m preparing a historieta about a personal experience that still I can’t entirely believe happened, that has kept me, in a way, hypnotized since it happened 25 years ago.

And later I‘ll be taking on the drawings for Zorba the Greek.