I met James Romberger and Marguerite Van Cook at a diner in the East Village, across the street from Tompkins Square Park—the neighborhood they have inhabited since the early eighties, when they became part of its community of young artists. The area was at the heart of a rejection, in that decade, of the art world’s moneyed uptown and SoHo galleries. The East Village’s storefront galleries, particularly Romberger and Van Cook’s Ground Zero, championed what was then considered noncommercial work—performance and installation art—as well as an emerging postmodernist, activist style. The scene, however, was short-lived, in part because the AIDS virus quickly decimated the tight-knit society, cutting short the work of artists in the prime of their careers, including that of David Wojnarowicz, one of the era’s brightest lights, who died in 1992 at the age of thirty-seven.

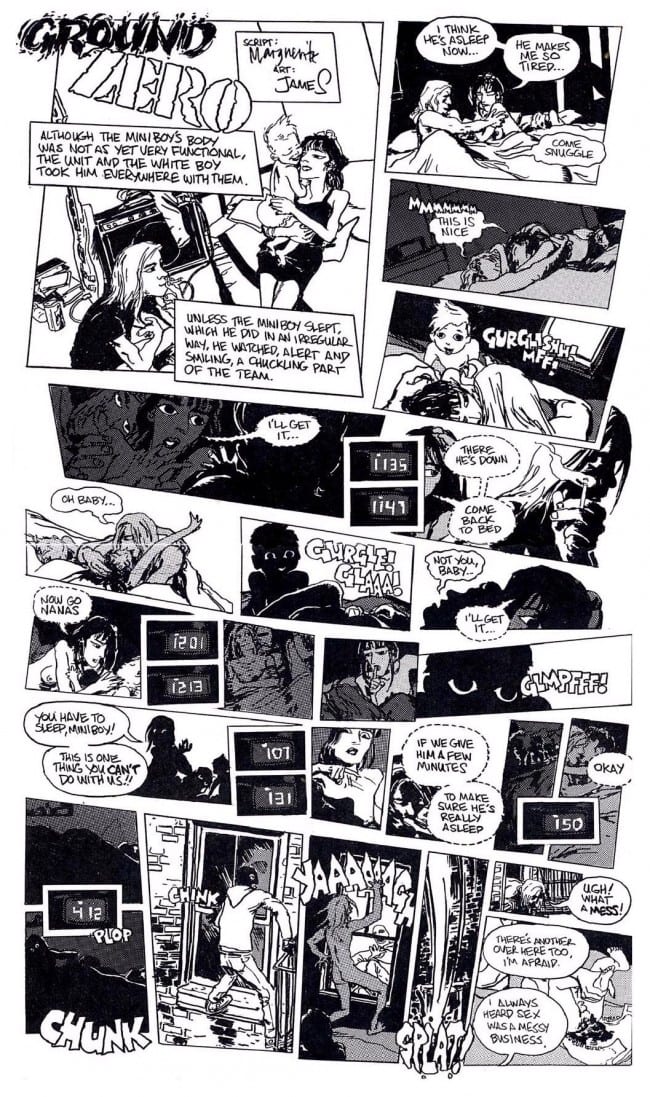

In the last years of his life, Wojnarowicz embarked on a book-length comic with Romberger and Van Cook in which he sought to chronicle episodes from his life: his early years and youth as a hustler and, later, his feelings regarding the AIDS crisis. Working with Wojnarowicz, Romberger edited the texts and drew the art; Van Cook (who is too frequently undercredited for her essential contribution) colored the pages after Wojnarowicz’s death. Published by Vertigo in 1996 and now reissued by Fantagraphics, 7 Miles a Second records raw and unsettling experiences by way of images and colors that are meant to disturb and to evoke the emotional tenor of a fraught—though occasionally hopeful—life.

Romberger and Van Cook are avid conversationalists, and we spoke also about their other projects, including Romberger’s Post York, which has been nominated for an Eisner for “Best Single Issue (or One-Shot).” So I was dismayed when, at the end of the lengthy interview, my recorder froze and erased the entire thing. But Romberger and Van Cook were game to try again after a week, and the second time held.

Their eagerness to talk about Wojnarowicz and the project, to remember all of it despite the pain of recalling his death, strikes me as a kind of bearing witness—testifying to Wojnarowicz’s life in much the same way the book does. Of that period in America, Avram Finkelstein, cofounder of Silence=Death Project, wrote, “What will be said of the first days of AIDS, long after pharmaceutical interventions have blunted our cultural memory? Hopefully we will say there was a time before we knew what we know, and many people died. There was an outcry and it mattered.”

How did your gallery, Ground Zero, come about?

Van Cook: In 1984, promoter Steve Lewis, of Danceteria, invited us to do a show encapsulating the East Village art scene, and so we spoke to the all the people and galleries around the neighborhood. It was called “The East Village Look Again.” After that, we did “The Acid Test,” which was an accidental curation on our part. Someone wrote in a gossip column that we were going to do a show called “The Acid Test,” so we said what the hell and did it.

Romberger: It was actually the doing of the guitarist and gossip columnist who was staying at our house, Tony Heiberg. There was a gallery called Sensory Evolution, and I said we should do an acid show there because of the name of the gallery and then it was Tony who wrote in his gossip column in the local newspaper, The East Village Eye, that we were doing it. So the next morning, I had to go to the gallery owner, Steven Style and, though I don’t think he liked our work, he said that since it was it was already in print, he’d let us do it for one night.

Who were some of the artists in those early shows?

Romberger: David was in “The Acid Test,” and a bunch of people we knew from the scene. We got to know a lot of the artists from doing “The East Village Look Again.” We also went to all the galleries, and they each gave us several artists, so in that way we got to know everybody.

Van Cook: “The Acid Test” had been very popular. We ran into Dean Savard, who ran Civilian Warfare with Alan Barrows, and he said he was moving out of that space and why don’t you have the keys and take the show there.

Romberger: Dean had shown David’s art at Civilian Warfare, but Dean himself was an artist and he didn’t show his own work, and nobody had ever asked him to be in a show. But we had asked him to be in “The Acid Test.” He was so thrilled that when we ran into him in the street he wanted to rent us his space, so we moved in and lived in the back and we put “The Acid Test” in the front. And that’s basically how we started running Ground Zero.

Van Cook: And then we made it to the front page of the Sunday New York Times. For our second show, we had Robert Costa curating. Critic Grace Glueck came by on her bicycle—she was doing a comparison of uptown and downtown galleries and set us up as the real deal. So our second show, in 1985, got the front page of the Sunday Times. Limousines were pulling up all day trying to buy the artwork that had been reproduced in the Times, and Calvin Reid—it was his work—didn’t want to sell it. So we said, I guess we’re in this business.

The comic strip, Ground Zero, preceded the gallery, right?

Van Cook: Yes, the comic strip was Ground Zero, and then the gallery became Ground Zero.

When did you start the strip?

Romberger: In 1984, in The East Village Eye. We had a whole page.

Van Cook: We wanted to reference, chronologically, the events surrounding where we lived and who we hung out with. It’s all in the comic.

How long did you do the strip?

Romberger: It started out as a full tabloid page, then they got more strips—Gary Panter, who did Dal Tokyo, and Wayne White and Lynda Barry—so they cut everybody down to smaller sizes and had two pages that were two-tier strips, maybe four to a page. Then, a few months later, they cut them down to very small pieces and then dumped it entirely. So the strip lasted for about eight months in the Eye, because in a newspaper the first thing to go is the strips.

Van Cook: But conceptually we didn’t really want it to be in one place, and I had the idea that it shouldn’t be easy for the reader to access. I wanted to break up any sense of how narrative works, so we wanted it to be in different publications at different times, in different formats.

Was that notion influenced by your having studied Roland Barthes?

Van Cook: Yes, the whole influence of semiology and semiotics.

Romberger: So it was in East Village Eye, Red Tape, Avenue E, Pretty Decorating—many, many small-press publications.

Van Cook: This was reflected in our work at the gallery, too. One of the things that was different about our curations is that we invited comics artists to show, making a space that was somewhere between comics and fine art. We didn’t want to close down any avenues.

How did you work on the script with David for 7 Miles a Second?

Romberger: David gave me the material and asked me what would work for a comic, and I picked things that would work visually. He established more control over the first part—of when he was a child—because he wanted to show himself getting picked up on Times Square and then getting taken to Nathan’s and then to a hotel room. For example, he’d given me pages of monologues, a couple of different people talking to themselves, and I drew a scene where he goes down into Nathan’s. I took one of the monologues, an older guy talking about his own son and imposed it on the character picking up David, and then took another monologue of a woman talking to herself about getting caught up by her trick and not being able to go see her children and imposed that on another character. I then had the two conversations running together. David thought it was great because it efficiently used the space to get two conversations going at once. It wasn’t technically true to his experience, but that’s how you would hear it.

So you selected all the text for the comic from what he gave you?

Romberger: The general scope of the narrative we worked out together—but I did the selection and then the editing of his texts. I cut them down as much as I could to keep what I thought was the most beautiful language. You don’t want the text to be redundant with the image, so you’re cutting away the extraneous material to get to the nut of the text. The process was heavy on editing, and David approved all that stuff in the first two parts.

If there was a place that needed dialogue, he’d write a little something to put in the balloon. Or he’d tell me dreams. I selected a few of his dreams that would work for me to draw. The giant wasp hanging over a banquet was one, and I could do a double-page spread of that and use the cinematic scope of comics to show something you’d need a big budget to film. In a comic, you can just draw it.

The third part wasn’t completed until after his death. How did you manage it?

Romberger: When it came to the third part, I had a lot less to work with. David had given me the gist of what he wanted, which was “I want to show myself at the current time, mourning the deaths of my friends, but then in the end it’s a beautiful day and I’m happy to be alive.” But by the time I actually got to sit and draw this thing and edit it—after David’s death—there wasn’t anything like that in his texts. There was no beautiful day, so the book ends with him dying.

He had done this really magnificent bit of writing that was in part of the Artist’s Space book that had gotten him in so much trouble with the NEA, and he had told me, Draw me huge on Fifth Avenue. By that time, what I remembered being on Fifth Avenue was St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and David had once gone with Act Up to protest the church’s stand against public health and homosexuality, while mass was going on, so it made it sense to make Fifth Avenue St. Patrick’s and to draw him smashing it. These were decisions I had to make, but they are true to what his intent would have been, as close as I could approximate.

Did he think there would really be a happy ending to the third part? Or that there would be something good to end it with?

Romberger: In a way it’s a vulnerability we all feel—no one really sees themselves dying and if David had been able to hold on another year or two, perhaps the combination therapy that was developed within a couple years after he died might have saved him. A lot of people were brought back from the brink of death, and it is incredibly tragic that due to actions of people like David and others in Act Up—actions that got the medical establishment to loosen up on the approval of drugs trials—a lot of the work on AIDS and cancer was accelerated. And yet so many people died because things were being held off.

Van Cook: People were starting to be diagnosed and become ill, but that was something David wrote to us about in a letter—I’m rejecting that particular view of life and I’m going on to this brighter path. He didn’t want to be celebrating death and darkness anymore, as an artistic trope. He didn’t want to go down that artistic road, he wanted to go somewhere else. So even when things happened to him later on, he had embraced that more hopeful aspect.

What was he hopeful for, do you think?

Van Cook: A life that had some good in it. I don’t want to put words in his mouth.

Romberger: It wasn’t really born out by the factual matter of what happened. There’s a spread in the book of the train that’s referential to his own paintings of trains—he did several of them, in which he depicts the wheels spewing shit and language. That particular text is very bleak and nihilistic, but I think it’s unavoidable. On the other hand, I’m a little sensitive to the fact that a young person could read that material and feel a very dark place. I was a little hesitant to go that route, but you can’t avoid what happens in the end of the book—he dies.

Van Cook: He really loved our son Crosby, and there were a few times when David took him out in the stroller, but he was very nervous about what interacting with a child would do, because we didn’t know what the disease was about early on. David was tested three times before he had a concrete diagnosis. Emotionally it was terrible.

I think what James did such a good job of bringing out in the last part of the book is David’s distress, to put it mildly. It’s a response to real events, as opposed to living a lifestyle that manufactures anxiety.

That’s an interesting distinction.

Romberger: The first part is very pointedly about David’s trick and the lack of empathy the guy feels for what he’s making David watch through that hole in the wall. And David’s shocked—that the trick has no inkling of what the woman on the other side of the hole is feeling. I purposely made that the point of the last part, to come back to that idea at the end, where David is in his room and is alone, and it’s me calling on the phone. He lets the machine pick it up, and he thinks, People don’t know where I am, I start to hate healthy people because they can’t feel what I’m going through. And he talks about himself in the third person—“David’s in pain,” “David’s alone”—but it is about empathy, the only thing we have that allows us to touch each other. So if there’s anything positive to be taken out of the book, it’s that we should be working toward a more empathetic experience while we’re on the planet.

Van Cook: He had on his answering machine a song we had recorded, “I’ll Be Loving You,” that is extremely bright. The lyrics are “If I could sing a song as beautiful as you,” and it was on David’s machine from when we came back from Belgium in 1991. It just stayed on there.

(continued)