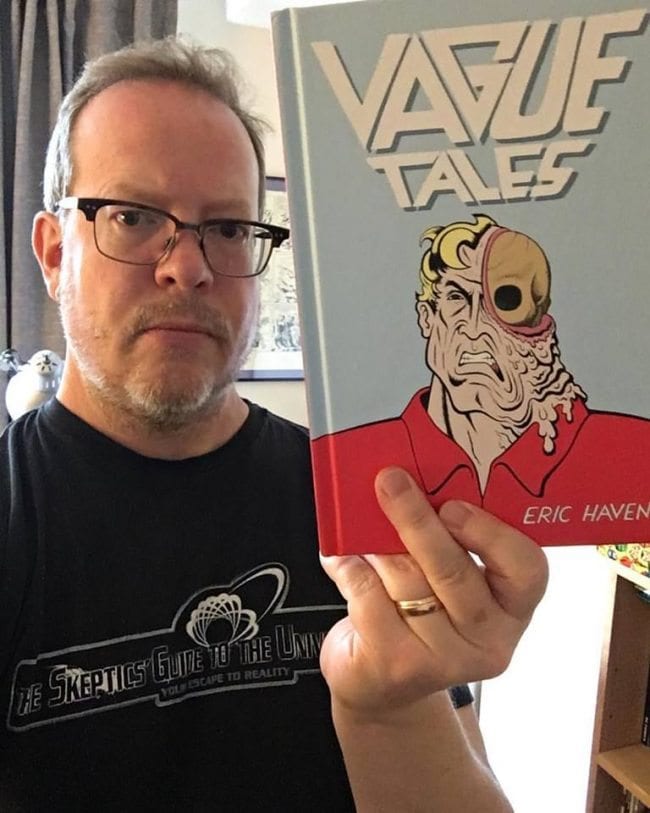

Eric Haven continues the tradition of Bay Area comic artists pushing the envelope with their own unique brand of storytelling. I first became a fan of Eric’s work when I discovered his comic series, Tales to Demolish, published by Sparkplug Comic Books. To read an Eric Haven comic is to be transported to another dimension ruled by other-worldly heroes, and where vivid, jarring imagery combine with unassuming, deadpan humor to turn the traditional science fiction narrative on its head. This is evident in Eric’s upcoming book, Vague Tales, where he chronicles a dizzying, mind-bending exploit inside a dream realm.

Eric Haven continues the tradition of Bay Area comic artists pushing the envelope with their own unique brand of storytelling. I first became a fan of Eric’s work when I discovered his comic series, Tales to Demolish, published by Sparkplug Comic Books. To read an Eric Haven comic is to be transported to another dimension ruled by other-worldly heroes, and where vivid, jarring imagery combine with unassuming, deadpan humor to turn the traditional science fiction narrative on its head. This is evident in Eric’s upcoming book, Vague Tales, where he chronicles a dizzying, mind-bending exploit inside a dream realm.

Eric and I chatted on the phone to talk about his beginnings in comics, 70s TV pop culture, how the Bay Area comics community has influenced his approach to comics and what a cartoonist’s role can be in politically-charged times such as these.

Rina Ayuyang: Eric, were you interested in comics as a kid?

Eric Haven: Yes. Some of my earliest memories are of comic books, of certain comic covers I saw on a newsstand or specific panels from a Jack Kirby monster story. But cartoons held an early fascination for me as well.

You grew up in the '70s, so what cartoons were you watching in particular?

I watched the classic Warner Bros. cartoons every Saturday morning. Also Tom & Jerry, Droopy, Scooby Doo… all the normal kid stuff. But the Hanna-Barbera superhero cartoons were particularly memorable. The Herculoids, Space Ghost, and Bird Man were really weird but strikingly designed characters and they made a strong impression on me.

I can see that in your comics. Your characters have a superhero comic influence, but there is a quirkiness, something humorous and human about them. The Hanna-Barbera characters like in Johnny Quest are serious men on a mission, but also melodramatic and comical. Do you see that quality in your own comic characters?

Wow, awesome, I’m glad you think that. I try to keep the earnestness and the ridiculousness in balance in my comics, and sometimes it results in comedy. When it does, I’m happy. But I’m also happy to just draw weird stuff. I love the weirdness of the Herculoids - not only the visuals but also the music and the way it’s edited. Weird sequences of cavemen throwing molten lava balls into the mouth of a dragon. It’s just very strange!

Do you find that your comics are nostalgic, like a look back at these characters from comics or cartoons that you enjoyed as a kid?

Completely. Although I don’t have any desire to return to those simpler days, nor do I think those days were better than now. Ultimately, I want my comics to be clearly understood both visually and narratively. Those comics and cartoons from my early childhood seem to best encapsulate that desire: simple designs, easily-grasped story.

When did you start working on your own comics?

A long time ago. I’ve always drawn comics, as long as I can remember, but they were almost never full stories. Usually it was just a splash page with the character’s name in bold letters hanging over an awkwardly-posed rendition of a superhero. I might get a few more pages into the story, maybe a bit of an origin, but I’d always abandon it and start a new one.

My first real comic was published in 1992. It was Angryman, published by Iconographix, which was an imprint of Caliber Press. They also published Ed Brubaker's Lowlife, Dame Darcy's Meat Cake, and Jason Lutes' Catch Penny Tales.

What was Angryman about?

It was about a 20-something guy trying to make his way through the world, but weird things kept happening to him. He was connected in an unexplained way to a psychotic superhero, and interacted with a tiny, flying Tiki monster. I wrote out full scripts and drew thumbnails for six issues. It was fun, it was exactly what I wanted to be doing.

How did you feel about your comics-making after that? Did you feel like you could make this a profession?

I hated it. Hated it!

Why?

After three issues of Angryman, I learned the hard truth: I’d never make a living in the comic business. I gave it everything I had, even quit my day job at the sake factory in order to fully commit to the art. But when I received the royalty check for the first issue - the princely sum of $100 - I realized my folly. In addition, seeing my comics out in the world started to fill me with dread. All I could see were the mistakes and the awfulness.

I stopped trying to produce comics for publishers at that point. Instead, I made mini-comics. That way I could still make terrible comics, and nobody but a few friends would see them. I could spend time flailing around and experimenting without fear of judgment. It was almost 10 years of mini-comics making before Tales to Demolish came out.

Did that start as a mini, or did Dylan Williams and Sparkplug Press publish it right away?

I designed it as a regular-sized comic and sent it out to a few different comics publishers, but never got a response. Some cartoonist friends suggested that I show it to Dylan, and when I did he said he’d like to publish it.

Did you know Dylan before you worked with him?

Yeah, he worked at Comic Relief in Berkeley. We hung out there. Before it was published by Iconografix, Angryman was a Xeroxed mini-comic. Comic Relief bought some copies and sold them in the back of the store with lots of other mini-comics. Dylan was great at pushing those hand-made comics, he truly loved the art form.

There was a strong indie comics community in the Bay Area then. Were you involved in any of that or were you a “loner” cartoonist?

More of a loner. You’re right about the comics community in Berkeley, but I didn't really feel like I was a part of it. I had a circle of non-cartoonist friends I hung out with socially, and foolishly didn’t recognize the benefits of networking with other cartoonists. Even so, it was comforting to know there was a group of artists around town that would regularly meet and share work.

How was your experience with Dylan and the various other publishers you’ve worked with? How have they affected how you do your comics?

I’ve had the great fortune to work with great publishers. Dylan was a very unique person. He understood comics from a variety of different angles; he was a historian, a teacher, a publisher, and an artist. Most importantly to my comics-making, Dylan was my introduction to some of the great cartoonists of the 1940s and 1950s. I had of course read books on comics, like the Smithsonian volumes of comics and newspaper strips, and whatever other books on the subject I could find at libraries. But Dylan used to make these mini-comics/zines of cartoonists like Bernard Krigstein, Mort Meskin, Ogden Whitney, Fred Guardineer, and lots of others. You can find any of these guys and unlimited examples of their work on the Internet now, but in the early '90s it was rare to come across it. Plus, seeing a bunch of complete stories from one artist bundled together so you can track their development or thematic idiosyncrasies was extremely educational. Fantagraphics is doing that now with all of their EC artist volumes, but Dylan did basically the same thing more than 25 years ago.

I can say the same for Alvin Buenaventura as well. Alvin had incredible taste in comic art and would show me work outside my normal comfort zone in comics. A lot of European stuff, some southeast Asian stuff that I’d never come across on my own and never even knew existed. Like Dylan, Alvin just wanted to share the work that excited him as a publisher and printmaker.

Since he had such a discerning eye, it was always good work and it’d always be very inspiring. I spent many hours in his warehouse flipping through pages of books and comics and prints, sometimes to the point of visual exhaustion.

And you worked with Eric Reynolds with Vague Tales...

I pitched Vague Tales to Eric a couple years ago and described it as “Cowboy Henk meets Void Indigo”. Honestly, I wasn’t even sure what the book was going to be about at that time, but those two esoteric reference points seemed to best explain the mix of weird humor and 1980s-era sci-fi fantasy horror I was going for.

In Vague Tales, you introduce an assortment of very strong iconic characters who could be lead characters for their own comic. How do you come up with them?

Well, it was mostly a visual process. I’d start with a drawing of the character, with no idea about the character’s backstory or how he or she fits into the narrative. I just wanted to experience the joy of drawing a cool-looking character. Their backstory and narrative purpose developed as I drew it. The intent was to create something formed from my unconscious mind, or whatever part of my brain that pushes the pencil around on the paper. It was very much like the experience of drawing comics when I was little, starting with a heroic-looking splash page and then building the story around it.

Going back to the Herculoids, there’s a feeling of epic excitement in the intro sequence of the cartoon. The characters are flying through space, smashing things, screaming. As a kid, that was enough for me! It didn’t matter what the story was about, my proto-cartoonist mind was triggered and locked in to enjoying the visual and audial experience. I think the characters and narrative in Vague Tales are an attempt to replicate that feeling.

In Tales to Demolish and in Kramers 7, you depict yourself as a character. How personal are these stories? There’s a glimpse of autobio, though your character is thrown into these faraway sci-fi worlds.

Yeah, sure. It’s autobio in that these stories feature myself and sometimes my surroundings. Always easier to draw what you know! But the stories quickly veer into absurdity with very little semblance to my actual life experience. I never named myself in those comics – the character looks like me, but he is never mentioned by name. That was probably enough to separate my true self from my comic self, or to keep myself from having a psychotic break or something.

In 2009, Alvin asked me to do a continuing strip for The Believer magazine and it was then I decided to give the “Eric” character a name different than my own: “Race Murdock”. But I have no desire to portray myself in comics anymore, or at least not right now in this period of my life. Especially stories where it's all about me getting destroyed in some way!

I don't know! For some reason, I thought it was always funnier to place myself into stories where the end result is death or dismemberment. It’s fun to see Wile E. Coyote get crushed or flattened or exploded, and then keep coming back for more. To me, those cartoons are the epitome of poetic self-destruction. So minimal! So hilarious! In Race Murdock, I decided to explore that idea of self-destruction, whittle it down, minimize it to such an extent that I could destroy myself within the constraint of a 4-panel strip. But after four years of Race Murdock, I think I got whatever it was out of my system.

In Vague Tales, the reader is looking into a world, especially with this first character we see, who is pulled out of current times into another world.

It's an experimental piece. I was trying to describe what it may be like to have a hallucination or to experience altered consciousness. There isn't any real plot to the story other than the character moves through time and space, perhaps in his own mind or maybe utilizing some form of mental telepathy, and at the end the book he's back where he started, only changed in some mysterious way.

It feels like there’s a huge backstory that's going on between them all these iconic characters in the story, like in TV sci-fi serials or soap operas, but the reader doesn't know what the story or connection is thus the title Vague Tales. I don't know if that was what you were thinking about when you were coming up with these characters, but do they have a connection?

I’ve always been interested in dream states and altered forms of consciousness. In this book, I’m trying to simulate those states of mind where strange connections or epiphanies are common. There is a connection between what all the characters are going through, but that connection is never specifically or technically explained. It's purely visual or metaphorical. Dreams are so powerful because they are operating on our own individual, highly personal symbolic system. I’m trying to replicate that by repeating symbols that hold special meaning. The front cover of the book mirrors the back cover and then you peel back skins, layers, as you turn the pages through the story, each one relating to the last, sometimes purely visually. For example: one of the characters, a silicon-based creature, has his head explode into multiple fragments, and then you turn the page and there is a full sized drawing of someone else's face. It cuts from one image to another, suggesting a connection between the two. I know I'm not explaining this clearly (and yep, that’s indicated by the title of Vague Tales) but I was trying to make this thing that is very much a dream, a hallucination, and to make an artifact of it and bring it out of that realm of dream and into the physical world. This book is that artifact.

It's very weird. I don't know if Vague Tales is going to have an effect on anyone else, but it is very personal to me. These images seem to make sense to me, and I wanted to string them along in a sequence that hopefully elicits a reaction in the reader. I don’t know if that's going to be the case; it's an experiment. I have no idea what the reaction is going to be. I'm very happy that Eric took a chance to publish this thing; it's a very personal work that I felt compelled to create.

I understand that -- the need to share and express as an artist no matter who gets it. And I can also see the progression from you portraying yourself in your earlier comics as an obvious way to show that the story is personal to you now being totally comfortable just throwing your entire self, mind and body, into this world that you've created that makes the story ALL you in a sense.

Yeah, that’s right. Instead of having the story being ABOUT me, the story actually IS me. Maybe the experience of reading the book is like spending time in my subconscious. Being a cartoonist is a weird thing as I'm sure you're aware. Feeling this need to put these images out there…I don’t know why. I haven't really questioned why these images are resonant within me. I just put it all out there. It may mean nothing...[laughs], but…

...Or does it have to mean anything to anyone else

Right! Does it? [laughs] I don't know. My answer to that question might change year to year, project to project. Why have I taken time out of my life to do this thing? Why am I compelled to make these images? This book doesn’t answer any of those questions. In fact, just the opposite: I opened my mind and just let whatever was in there to spill out. It may be ridiculous imagery, it may be infantile or lurid, but I felt the compulsion to get it out. And it's come at great cost, actually.

How?

Taking great chunks of time off from work, for example, time that was, purely from a financial point of view, perhaps better spent being gainfully employed.

And why are you compelled to do this in a comics form? Why comics, why not painting or something else? Painting would be the first medium that comes to my mind as way to express what one is feeling as opposed to comics.

Comics, for me, is how you just described painting. Comics, for me, are the ultimate art form, one that allows the artist to express himself or herself through words and pictures equally. The human brain is hard-wired for language and for visual symbols, so comics are actually the most efficient way to communicate. Putting words and pictures together, and then putting them in a sequence on a series of pages, is highly evocative and possibly even more descriptive than either painting or writing on their own.

Seems more accessible too.

Accessible, yes, but also more accurate. If the intent of the artist is to communicate his thoughts and ideas as efficiently and truthfully as possible, I think using words in combination with pictures would be the best method.

Speaking about how this medium for you is a way to just get everything within you "out there", I want to talk about The Resister. Many artists are responding to the election and the current political climate here in America through various ways like sharing articles and viewpoints on social media, but what prompted you to go further and draw a comic specifically about this?

That was rage. Pure, unadulterated RAGE. I've never felt so angry about our political situation, not even during the Bush years. I think anyone with a shred of rationality should be working to resist 45 and his administration. It's abhorrent what has happened; I literally can't believe it. I'd like to think that Americans are at least semi-educated and reasonable, but this election showed that a significant portion of our population is backwards, bigoted, misogynistic, and hateful. I’m really concerned about this.

When did you start working on it? Was it right after the election, and also was it a purely therapeutic thing, dealing with what's going on politically or a call to arms?

When did you start working on it? Was it right after the election, and also was it a purely therapeutic thing, dealing with what's going on politically or a call to arms?

It was not purely therapeutic because I still feel the rage. It's ongoing. It didn't work. [laughs]

So there are more Resister comics to come. [laughs]

Maybe. The social media echo chamber seemed to enjoy it! I started drawing the comic the week he took office, after realizing I couldn't even think about anything else, "How did this happen?! This is insane! A new, terrible reality has usurped our entire existence!" I just couldn’t understand it or believe it, so the comic was a way to direct all the rage outwards.

How much do you think that artists should be focusing their time now on making more political art as a part of The Resistance? What's your take on artists' contributions to the whole cause?

That's a good question, and it’s a question I continually ask myself as well. Is it more important for me to go to a science march, or stay indoors and do more Resister comics? Just for me personally, funneling the rage into comics may have a longer-lasting effect. But I’m not advocating drawing comics over marching and demonstrating and calling representatives. Everyone should be resisting, but everyone should do it in their own way. Resist!

From your on-going experience of not making any money from comics [laughs], what can you say to those young artists and students attending comic schools and different comics programs in colleges?

I wouldn’t know what to tell them. Maybe I’d suggest they read “Art School Confidential” if they haven’t already.

In 1989 when I graduated, I had a degree in Illustration from Syracuse University and thought, “okay, I’ll be an illustrator”, but getting started in the field of freelance illustration is really, really challenging. I would say to people who are studying comics to just try to do the best work you can while recognizing that your work might never get published, let alone make any money. Just do it because you like it. Enjoy it as means of self-expression.

That’s true, I mean where else, I guess besides film maybe, can you show off something so graphically charged like a maimed corpse or something.

Yeah, you can do whatever you want and the only limit is your own imagination. And making comics can be infinitely more satisfying than filmmaking if you prefer complete artistic control over collaboration. Just one lone cartoonist, transmitting their thoughts through words and pictures directly from their brain to yours over time and space -- It’s a very pure art form.