As one of the twin pillars of Fantagraphics Books, Kim Thompson helped the comics medium to grow up. He did so with the tough love of a strict parent; the profound, internationally formed intelligence of a global citizen; and the abiding loyalty of an avid comics reader.

When he passed away June 19, 2013 at age 56, Thompson left a tragic and unexpected void in the world of comics publishing, but he also left ongoing waves of prospects, projects and trends that he had helped to engineer. His influence will be felt for a long time to come.

As huge an impact as he had on the American comics scene, Thompson did not grow up in the U.S. (he lived only for two brief times in the U.S. in the late '50s and in 1964). He was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, in 1956. His mother was a housewife and his father was an American computer programmer who worked as a civilian contractor for the U.S. Army. His father’s work kept the family moving, and over the years they lived in France, Holland, Germany, Thailand, and the West Indies. Attending schools largely in France and Germany, he received a French baccalaureate.

Growing up, Thompson was exposed to Hergé’s Tintin, Franquin’s Spirou, Peyo’s Smurfs, and other European comics, but he also became a Marvel Comics enthusiast through French translations and the U.S. comics he purchased at American military Post Exchanges. “I think I was responding to what everyone was responding to,” Thompson said. “I loved and still love European comics, but something like the American comics back then can be a breath of fresh air. The pulpy excitement of them. Then, of course, there’s the whole Marvel world where everything is interrelated and the Stan Lee Soapbox kind of thing — there’s nothing like that in European comics.” He had several fan letters published in various Marvel comics in the early- and mid-’70s.

Thompson’s traveled youth left him with a partial command of 10 languages. He was fluent in English, French, and Danish, and could read Spanish, German, Norwegian, and Swedish. He also developed a working knowledge of Italian, Dutch, and Latin.

For a time he considered working as a translator or linguist, but, in 1977, the Thompson family moved to the U.S. Shortly thereafter, he met his future publishing partner Gary Groth when the two were introduced by the writer Frank Lovece.

Groth and Michael Catron had formed Fantagraphics in late 1974 and had begun editing and publishing The Comics Journal out of Groth’s apartment in College Park, Md., in 1976.

“Within a few weeks of [Thompson’s] arrival,” Groth said, “he came over to our ‘office’ — which was the spare bedroom of my apartment. It was a fan-to-fan visit. Kim loved the energy around the Journal and the whole idea of a magazine devoted to writing about comics and asked if he could help. We needed all the help we could get, of course, so we gladly accepted his offer. He started to come over every day and was soon camping out on the floor. The three of us were living and breathing The Comics Journal 24 hours a day, as scary as that might sound.”

Thompson not only stepped into the breach of the ongoing workflow, he bailed the company out of the first of its occasional financial crises by turning over a $1,000 educational nest egg from his grandparents. According to Catron, “I’m sure we were up to our eyebrows in bills as usual, and he offered to tap this fund to get us out of it. I’ve never thought of it as Kim’s buy-in of the company.” He was already working for free and when he perceived that the magazine needed the money to survive, he handed it over, no strings attached.

It was soon clear that Thompson had become an integral part of the Journal and Fantagraphics. Recalling the early days of the company in the Fantagraphics oral history, Comics As Art: We Told You So, Groth told Tom Spurgeon, “At some point, maybe a year after he arrived, we simply gave him a third of the company. I remember the three of us discussing it in the living room of my apartment. He was putting in as many hours as we were and was as fully involved in the magazine as we were. He was, as [Joseph] Conrad, said, one of us.”

He filled a gap left by Catron’s yearlong departure to work at DC Comics in 1977. When Catron chose not to relocate with the company when it moved to the West Coast in the 1980s, Thompson’s third became a half, with Groth and Thompson sharing equal ownership as the company reincorporated in California.

In its various Maryland, Connecticut, and California bases — before moving to its current home in Seattle — the atmosphere at Fantagraphics and The Comics Journal has been described as a mixture of anarchic bohemianism and absolute dedication. According to Journal editor Tom Heintjes, “Everybody kept crazy hours. Everybody would sleep in and work until the wee hours. Kim was especially notorious for working into the wee, wee hours and waking at the crack of noon. You could come to work in your bathrobe if you wanted, or the T-shirt you slept in and everybody was having a great time. Hell, we’re putting out comics!”

Hate cartoonist Pete Bagge remembered a visit in late 1983 or early 1984: “I was greeted at the door by Kim Thompson, still in his bathrobe at 1 p.m. He was in the middle of grilling his ‘breakfast,’ which consisted of the biggest hamburger I’d ever seen and the smell of which inspired the rest of the Fantagraphics staff — which at the time was a mere handful of young, hyperactive, nerdy white guys with names like ‘Hiney’ and ‘Peppy’ — to cook up similar ‘breakfasts’ for themselves.”

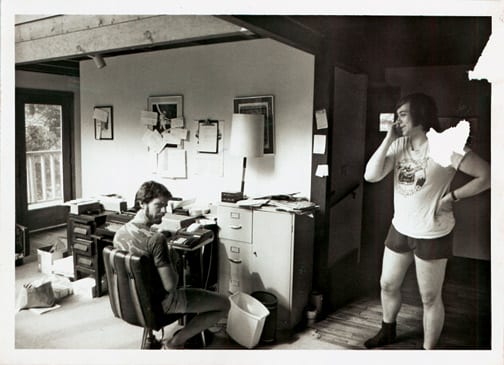

Gary Groth (sitting), Kim Thompson at the Fantagraphics "offices," Stamford, Connecticut, circa 1982.

Amazing Heroes graphic designer Dale Crain: “Kim is one of the hardest-working guys I’ve ever known (and the bastard made it look so easy) and I think I recall us actually racing to see if he could produce copy faster than I could design and lay it out.”

Thompson recalled, “I used to get so fucking tired. I learned how to fall asleep on the bus to my day job [in Maryland] and wake up at my stop. I learned how to go in for a 30-minute lunch break at work, drop my head on the table and fall sound asleep in five seconds. My job involved climbing ladders and I fell asleep at the top of the ladder several times. I eventually quit that job and got one that didn’t involve ladders. It seemed safer.”

Thompson was a major force in Fantagraphics’ gradual expansion beyond The Comics Journal into comics publishing. His European respect for worthy anthropomorphic cartooning allowed him to shepherd into print Stan Sakai’s Usagi Yojimbo and the 50-issue (1985-1990) funny-animal anthology series Critters. Sakai said, “My relationship with Kim established my relationship with all my editors: ‘Leave me alone.’ Kim gave me absolute free rein. I turned in complete stories, fully drawn, then he did some editorial corrections — spelling, etc. There was only one instance I can think of where he actually asked for a change. I had drawn a panel with Usagi splitting a guy’s head open with blood and bits of brain flying out. He thought that was a bit too much, but I had shown the story to my wife, who objected to that panel and I had already toned it way down. It’s probably then that I came up with those ‘floating skulls’ to indicate death.”

Thompson was equally involved in the primary aesthetic thrust of Fantagraphics, which was the publication of edgy, ground-breaking alternative comics that couldn’t find a home anywhere else. His other anthology series was the very alternative Zero Zero, which ran from 1995 to 2000 and included work by Kim Deitch, Dave Cooper, Al Columbia, Spain Rodriguez, Joe Sacco, David Mazzucchelli, and Joyce Farmer.

Although Groth and Thompson were closely allied in their aesthetics, their respective viewpoints were distinct enough that Fantagraphics’ output is often perceived as divided between “Gary books” and “Kim books.” The Comics Journal itself remained essentially a Gary book. Thompson, with his slightly greater tolerance for mainstream comics, took over Amazing Heroes from Catron and became its guiding force. Thompson said, “As the Journal became more focused on independent and more challenging work, we could have a magazine that covered the more fannish aspects of comics. Amazing Heroes wasn’t too far away from the earliest Comics Journals.”

Although he tended to describe Amazing Heroes as adhering to a lower set of critical standards than the Journal, Thompson nevertheless took pride in the magazine, which ran for 204 issues from 1982 to 1992 and it is remembered fondly by readers. “There’s a lot of good stuff in AH,” he said. “Arguably, it was a more … cohesive magazine than the Journal, which could sometimes fly off the rails or get caught in eddies of self-indulgence or obsession. I thought Gerard Jones’ reviews were as good as a lot of The Comics Journal’s reviews and we did some great special issues, especially [managing editor] Kevin [Dooley’s]. The foreign-comics issue with the Valerian cover I think had some of the best and most comprehensive coverage of European translations anywhere. And in terms of effectiveness, I think AH’s coverage of alternative comics may have ultimately been more useful in terms of getting in new readers than the Journal’s sometimes preaching to the choir. I think AH started out as a cynical money-making ploy and ultimately transcended that. It was a good magazine for superhero fans with at least a slightly open mind. And it was a lot of fun to put together. No regrets from me!”

Probably, Thompson’s greatest contribution to Fantagraphics and to American comics readers has been his championing of European imports. The publisher’s first attempts in the 1980s at publishing translated editions of European comics were stories by Danish cartoonist Freddy Milton and Hermann’s post-apocalyptic Western Jeremiah [under the U.S. title The Survivors], which became a cable TV series in 2002. Critters readers enjoyed Milton’s stories but Jeremiah did not fare well in the American marketplace. Carlos Sampayo and José Muñoz’ Sinner books didn’t do much better in 1987.

Thompson persisted, however, and the works of European cartoonists like Jason, Lewis Trondheim, and Jacques Tardi have become a prominent and much-lauded part of Fantagraphics’ line-up. Thompson translated almost all of the foreign comics Fantagraphics has published. Recent releases have included Tardi’s It Was the War of the Trenches, Jason’s Low Moon, Ulli Lust’s Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life, Lorenzo Mattotti’s The Crackle of the Frost, Gabriella Giandelli’s Interiorae, and Guy Peellaert’s The Adventures of Jodelle.

“I’m more invested in these books,” Thompson told Amazon blogger Heidi Broadhead in 2009, “because I work so hard on them and in many cases, of course, such as Tardi, I’m literally fulfilling a childhood dream by translating them.”

In a 2011 interview for wordswithoutborders.org, Dot Lin asked Thompson what Franco-Belgian comics bring to the American comics scene. He replied, “All-ages entertainment that isn’t stupid. Also, there’s simply a style and a level of craftsmanship in the best of the Franco-Belgian classics that is nowhere to be found nowadays. If you look at a page of Macherot, for instance, there is literally no one in American comics who has that pure, simple, straightforward ability to tell an exciting and funny story. Franquin draws better than anyone before or since. He’s literally the greatest comics draftsman in the history of comics and I say this without a shred of exaggeration. So this is stuff comics readers need to see, in the same way that cinephiles need to see Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin movies.”

Those who have worked with Thompson over the years know that he never minced words or shrank from hard truths.

Alternative cartoonist Dan Clowes said about him, “Has anyone mentioned the Kim Thompson compliment? That’s something every cartoonist I know talks about. This is a made-up example, but a Kim Thompson compliment would be, ‘Oh, we got the sales on your new issue. It’s really good. Really high sales. Can’t say it was my favorite, though.’ It’s always two things that cancel each other out. Every cartoonist I know talks about it. You get hardened after a while, but the first hundred times … Early on he was complimenting a comic of mine, Eightball #4 or something, and I was so buoyed by his compliments, and then at the end he’s like, ‘I guess now that I’ve told you how much I liked that one, I can tell you how much I didn’t like the one before it.’”

And cartoonist Richard Sala said: “Kim has a funny way of bursting your bubble. My favorite example of all time is when the first issue of my comic Evil Eye came out. Kim said, ‘Good news, Richard — Evil Eye #1 just got a rave review.’ (Pause.) ‘Unfortunately it was written by one of the worst hacks in comics.’ It’s kind of a lovable trait, actually.”

Not all of Thompson’s judgments were mixed. Journalist/cartoonist Joe Sacco worked for a while as an editor on The Comics Journal and when he thought of self-publishing his own work [Yahoo] he ran it by Thompson. “I wanted Kim to tell me what he thought of the work. I wanted another assessment. Kim wrote back, saying, ‘We’ll publish it.’ That really hit me over the head. That was good news. And then I began a relationship with them on a different level.”

Upon Thompson’s death, Catron reflected, “Kim’s loss will have a profound impact upon Fantagraphics, but he was fiercely and justly proud to have helped build a company that is like no other in comics history — and to have made it good enough and strong enough to carry on without him. And that’s precisely what he wanted us to do — carry on. We will do so, of course, but we’ll be doing it with a little less spring in our step.”

Fantagraphics associate publisher Eric Reynolds added, “Kim was my friend, a partner in the trenches, a mentor, a role model, and a near-daily presence in my life for the past 20 years. I looked up to him immensely, he was one of the most whip-smart and unpretentious people I’ll ever know, and I can’t believe he’s gone. It makes me sick that we won’t have access to his deep reservoir of knowledge anymore, or his critical eye that I never stopped learning from and probably never will.”

Groth concluded, “Kim leaves an enormous legacy behind him — not just all the European graphic novels that would never have been published here if not for his devotion, knowledge and skills, but for all the American cartoonists he edited, ranging from Stan Sakai to Joe Sacco to Chris Ware and his too-infrequent critical writing about the medium. His love of and devotion to comics was unmatched. I can’t truly convey how crushing this is for all of us who’ve known and loved and worked with him over the years.”

Thompson, a non-smoker, was diagnosed with lung cancer in late February; he died on the morning of June 19. Kim Thompson is survived by his wife of 17 years, Lynn Emmert; his mother, Aase; his father, John; and his brother Mark.

(Many of the quotes used here first appeared in Comics As Art: We Told You So, an oral history of Fantagraphics compiled by Tom Spurgeon that remains unpublished and unfinished, although the first three chapters are available on the Fantagraphics website.)

Tributes to Kim Thompson will be collected on this site in the near future.